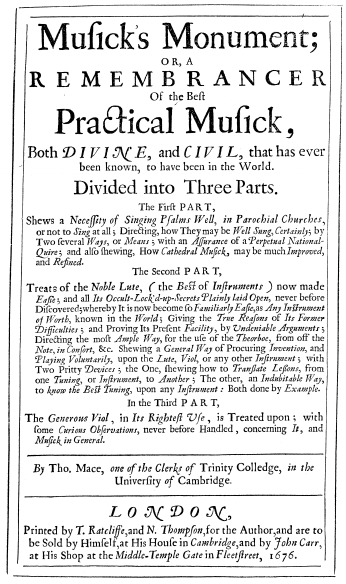

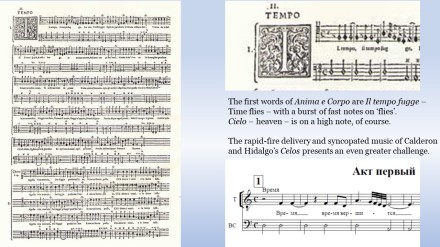

Tomas de Santa Maria’s Arte de tañer Fantasia (1565) free to download here is a teaching book for keyboard instruments and vihuela. Like Milán’s (1536) book for vihuela El maestro read more here, this publication is intended not only to teach the rudiments of notation and instrumental technique, but also to give detailed information for high-quality performance and to empower students to improvise their own Fantasias, in the strict polyphonic style of the late renaissance. Thus, the second part download part 2 here offers a complete introduction to 16th-century counterpoint.

In this post, I offer a brief overview of the contents of the two volumes of the Art of playing Fantasia, and analyse in detail Tomas’ comments on his highest priorities, Time and Rhythm, as well as his remarks on Ornamentation and on Performance Practice in general.

The Art of Fantasia

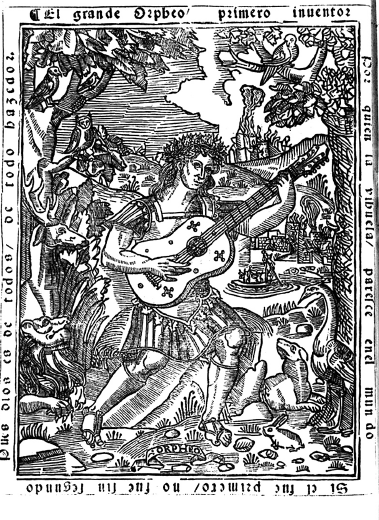

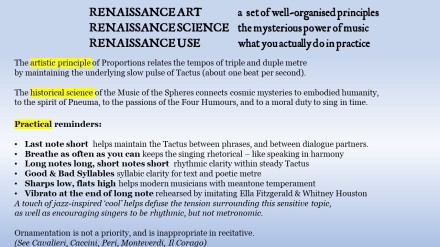

Tomas presents improvised Fantasia-playing as a renaissance Art, a term which had quite a different flavour almost half a millennium ago. Whilst the 20th century has taught us to regard art as the triumph of a lone genius over rules and restrictions applying only to ordinary folk, in the 16th and 17th centuries Art was defined as a system of coherent principles that transformed raw nature into artful creativity, full of life and grace. More about the period meaning of Art and period terminology here.

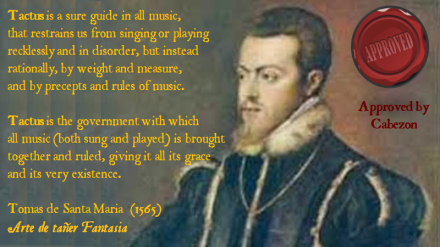

As Renaissance Art, Tomas’ fantasia is improvised within the rigorous structures of Franco-flemish polyphony, inherited and developed by such composers as Antonio de Cabezon (who checked and approved Tomas’ work), and his arte is indeed a book of rules: 78 chapters of detailed prescriptions, plus several bonus sections on key Performance Practice topics.

The remainder of this article consists mostly of extensive quotes from Tomas’ book, so for clarity my brief comments below are in blue.

Prologo: principles & fundamentals

El fin de este libro es arte de tañer fantasia – “the aim of this book is rules for improvising, divided into two parts. The first deals with all the pre-requisites that are necessary to begin improvising… the second part deals with everything necessary for this purpose, which is to improvise counterpoint, all put into a system (puesto en arte) and into universal rules (reglas universales)…

“In this first part we proceed by way of easier and clearer matters, beginning with the names of the notes (signos), but our principal intention is only to teach young professionals in this discipline (arte) what they need to put into practice, step by step from the most obvious and lightest matters, towards greater matters, and not [beginning] with the most demanding and difficult matters, which would tend to confuse and intrigue experts in such questions rather than enlightening and educating those new beginners, who like children should be nourished with light sustenance, easily digested, and later with more solid food!”

“In all the sciences and disciplines such order is essential… we see the same in Nature, which proceeds from imperfection to perfection… This has been the reason and motivation for our setting out to begin the first part with the notes, not as they have previously been analysed, but from first principles and fundamentals.”

Science, Art & Use

Tomas’ Prologue also includes a discussion of the need for arte – a coherent set of principles, contrasting this with uso – use, i.e. the habitual way of ‘just doing it’. Such use is not necessarily bad – a good habit can be a useful skill – but it must be guided by arte – rules. Our modern-day understanding of ‘art’ as the engagement with mysterious beauties beyond everyday rules is Renaissance Science.

Tomas’s personal connection to the ineffable, divine aspect of Music is proclaimed in a lengthy exposition of the role of Music in the Bible and in Christian doctrine. Reluctantly, he leaves this topic, to focus on the subject of his book – arte as a set of principles.

‘But I wish to leave this [Science], about which much more could be said, so as not to depart from my main purpose. And I say that although I have served the institution of my Order by playing organ wherever my duties took me, I considered many times the great effort required until now, and the many years taken up by learning singing and playing. Moved by emotions of love and charity, I began to investigate and re-examine how all this might be expressed as arte – a set of principles, so that in a short time and with less effort one could acheive the goal, and not merely as uso – habit, ‘just doing it’.

‘Because habit is broad and risky, whereas principles are narrow and sure. And so we see from experience that no-one without principles is perfect in their skilled discipline (facultad); because those who go without principles are like those don’t know the way and go without a guide; and like those who go in the dark without light. Since principles are the guide and the light, then it’s quite fair to say that those who do creative work (obran) without observing principles are ignorant.

‘This is the declaration of the Philosopher, who was asked what knowledge is; and who replied that knowledge is understanding the matter from its causes and first principles (primeros principios), which is what arte consists of.’

And so Tomas spent 16 years of ‘incalculable and incredible work‘, consulting with high-level colleagues, in particular Antonio de Cabezon, in order to perfect his set of principles, and teach his arte as ‘universal rules‘.

Contents

Part 1 begins with the names of the notes in plainchant (canto llano) and staff-notation (canto de organo); the three Hexachords (propriedades); the contradiction between the hard and soft Hexachords (see below); changing Hexachord (mutacion); the two pre-requisites for singing from staff-notation.

Then follows an extra section with ‘advice for maintaining the Tactus (compas) well, analysed in detail below.

Chapter 6 continues with note-values; introduction to the keyboard; semitones; black and white keys; intervals etc. Chapter 13 deals with Performance Practice, setting out eight conditions for fine playing (see below), which are discussed point by point in the following chapters.

From Chaper 20, Tomas explains how to perform polyphonic works on vihuela or keyboard, including advice on ornamentation. Then he analyses the Church Tones, Renaissance Modes, use of remote tonalities and Cadences.

Part 2 is devoted to the rules of counterpoint in 51 chapters: dissonance and consonance; suitable progressions, ascending and descending, whether in slow notes or faster; voice-leading; formal design. Chapter 52 has advice for new players (see below). The final chapter shows how to tune keyboard instruments and vihuela (in meantone).

Hexachords

Whilst every musician understands that one shouldn’t mix up B-flat and B-natural, Tomas’ comments on the contradiction of the hard and soft Hexachords – la contradicion que ay entre las dos propriedades de bequadrado y bemol (Part 1, Chapter 3) are interesting in the context of musical expression and History of Emotions.

‘Of the three Hexachords, the two that are B-natural and B-flat are notorious for being mutually repugnant and contrary – muy notorio ser repugnantes y contrarias entre si – and to such a degree that in no way can they suit or conform one to another nor vice versa, unless there is a particular necessity to make some perfect fifth or perfect fourth, or to excuse some dissonance of fa against mi… Finally, if we are singing or playing in B-natural, we must necessarily avoid singing or playing with B-flat [and vice versa].

‘The reason and cause of this contradiction and repugnance is because song with B-flat is a soft, sweet and smooth song (blando, dulce y soave), and on the contrary, song with B-natural is hard, strong and bitter (duro, rezio y aspero), and so – like soft and hard – they are manifestly opposites and contraries.’

The natural Hexachord [C D E F G A, containing neither B-flat nor B-natural] is halfway between the hard and soft Hexachords, conforming with either of them’. Tomas links this ‘convenience and conformity’ to the structure of eight-note modes, which combine notes from two six-note Hexachords. ‘The natural Hexachord is halfway, a tempering and concord … with which every mode (tono) can complete its perfect operation.’

Pre-requisites

Part 1, Chapter 5 De dos documentos para en brevemente cantar canto de organo – two pre-requisites for quickly [learning] to sing from staff-notation

‘It is certain and evident that staff-notation – canto de organo – is highly important and necessary for the player, both to understand what they are playing as well as to set a work [i.e. arrange polyphony for solo instrument] and gain advantage from [studying] it. Just as a scholar to complete his diploma has to read many learned writers every day… so the player should… set works in staff-notation by selected composers every day, enriching his knowledge of new and fine things… Por falta de fundamentos se gastava mucho tiempo…‘

If you lack fundamental skills, you’ve been wasting a lot of time!

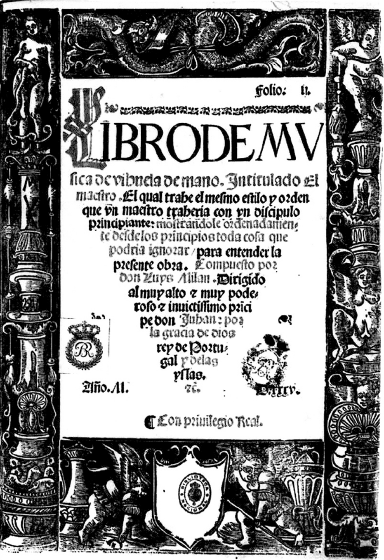

Tomas’ emphasis on staff-notation and deep understanding of counterpoint takes his book into territory beyond that explored by Milán in El maestro (1536). Milán uses tablature notation, which tells the vihuela-player which string to pluck with the right hand and which fret to stop with the left hand, note by note, and with careful control of rhythm. But this notation does not show the movement of the individual polyphonic voices, and Milán allows more freedom than Tomas de Santa Maria in adapting the strict rules of counterpoint to the exigencies of a particular instrument. Although Milán requires basic knowledge of staff-notation, his students learn to improvise polyphony mostly by ear and by ‘muscle memory’, by learning the stops and plucks that create the progressions and cadences of each mode. Tomas teaches staff-notation in detail and wants his students to learn counterpoint as an academic, as well as practical, exercise. But both writers encourage students to play good music, in order to learn by example, reproducing and imitating learnt musical fragments in their own improvised fantasias.

Tomas gives ‘two very brief and comprehensive rules (reglas), with which in a very short time one can easily learn and understand in depth: the first deals with compas and the second with written note-values.’

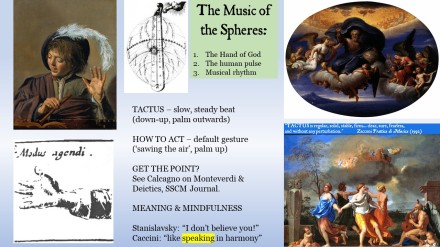

As for Milán (read more here), so also for Tomas, the term compas combines the philosophical concept of Tactus (the slow, steady pulse governing renaissance and baroque rhythm) with the practical, physical representation of that pulse as a down-up movement of the hand (or foot) and with the notation of the duration of a down-up pulse unit by the note-value of a semibreve and by a bar of staff-notation enclosed by bar-lines. Tomas distinguishes clearly between Tactus (the complete down-up movement, corresponding to a semibreve) and semi-Tactus – medio compas (downbeat only, or upbeat only, corresponding to the duration of a minim).

Tactus

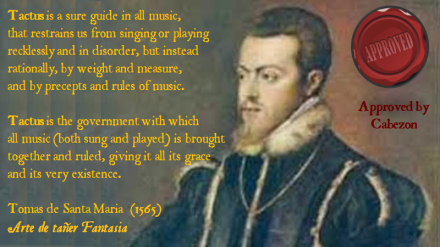

‘Quanto al compas, que es como fundamento del canto de Organo, por quanto siempre estriva en el, sea mucho de notar que la llave y govierno de toda la musica, assi del cantar como del tañer, es el compas y medio compas, de los quales el que bien supiere usar, terna bien fundamento para bien cantar y tañer, por que el compas es ciera guia en toda la musica mensurable que por su certidumbre le dezimos ser el freno de la musica, porque nos detiene para no cantar ni tañer desatinada y desconcertadamente, sino conforme a razon, por peso y medida, y por preceptos y reglas de musica. Y assi con justo titolo el compas es llamado el govierno con que se concierta y rige toda la musica, assi del cantar como del tañer, dandole toda gracia y ser.

‘Regarding Tactus, which is like the foundation of staff-notation, since it is always based on Tactus, it should be carefully noted that the key and government of all music, whether sung or played, is the Tactus and semi-Tactus. If you know well how to use them, you’ll have a good foundation for singing and playing well, for Tactus is a sure guide in all measured music [i.e. not plainchant], which for its certitude we can say is the musical brake which restrains us from singing or playing recklessly and in disorder, but instead rationally, by weight and measure, and by precepts and rules of music. And so it is the appropriate title to call Tactus the government with which all music (both sung and played) is brought together and ruled, giving it all its grace and its very existence.’

Tomas now links the practical purpose of Tactus as the basis of musical ensemble to its formal definition in relation to Aristotelean Time: ‘a number of movement in respect of before and after’ Physics (4th cent. BC). We should keep in mind that Isaac Newton’s theory of Absolute Time was not published until more than a century later.

‘Compas es medida, en la cantoria tomado a intento que las bozes concurren en consonancia a un mesmo tiempo. Tactus is Measure, used in choir so that the voices come together in consonance at the same time.’

‘Compas es la cantidad a tardanca de tiempo que ay del golpe que hiere en baxo a otro siguente baxo. Tactus is the amount of duration of time from one down-beat to the following down-beat.’

In the next paragraph, he links the physical hand-movement and practical purpose of Tactus-beating to the notation of musical time with bars and note-values.

‘El compas con que se mide toda la musica practica assi del cantar como del tañer fue sacado del compas con que se mide y inivela la cantidad a cuya semejança el compas de la musica practica mide el tiempo que se gasta en las figuras del canto de Organo… The Tactus that measures all practical music-making both vocal and instrumental is taken from the Tactus that measures and determines the quantity represented by a bar of musical notation which measures the time taken up by the note-values of staff-music.’

Tomas makes it abundantly clear that all measured music (i.e. all music except chant) is governed by Tactus, and the music has to conform to the Tactus, not vice versa.

‘El compas, en el qual estriva toda la musica practica… Tactus, on which all music-making is founded. ‘Toda la musica, assi del cantar como del tañer, esta subjectada y atajada al compas, y no la compas ala musica. All music, both vocal and instrumental, is governed by and founded on Tactus, and not the other way around.

About this, students who want to excel in this art should be well admonished.

‘The Tactus is divided into two equal parts, that is into two semi-Tactus… by the upbeat, so that the Tactus is always on the downbeat and the semi-Tactus on the upbeat’. Tomas emphasises that in binary metre every semi-Tactus is of equal duration.

‘There are two different types of compas in music-making – in one the Tactus is divided (as above) into two equal parts. In the other type into three equal parts: this is the compas of Proportion, also known as Triple metre, in which of the three parts that it has, two are spent on the down-stroke and the other one on the up-stroke. This is done singing two Semibreves on the downstroke and one on the upstroke [slow, Sesquialtera proportion] or two Minims on the downstroke and one on the upstroke [fast, Tripla proportion].

Four requirements for maintaining Tactus perfectly

- Beat time with the hand, down-up, with each stroke of equal duration

‘Even though the upstroke should not have a ‘bump’ [topar] as the down-stroke does, nevertheless the down-beat must hit as if it struck something.’ He mentions two faults to avoid: ‘often we see imprecise Tactus-beating without any ‘bump’ neither on the down nor the up, or hitting with the hand as if it struck something on down and up’. This subtle difference between down- and up-strokes is the concept of arsis and thesis. ‘Every bar has these two beats.’

- The hand stays down for the entire duration of the semi-Tactus

‘It is not lifted until the note on the upstroke. Similarly on the upstroke the hand stays up for the entire duration of the semi-Tactus, until the downstroke.

‘For this it is necessary to raise and lower the hand with equal regularity – una misma ygualdad.

- The up- or down-beat and the note on which it falls are struck together simultaneously – juntamente a un mesmo tiempo –

‘The beat is not before or after the note, the note is not before or after the beat, but absolutely together at once. For this, it’s necessary that each beat, both down and up, should be struck with a certain force or impetus, and in addition both should be struck equally, that is one doesn’t strike the downbeat harder than the up, nor the up harder than the down.

- Every bar goes as measured and determined by the measure of the first bar

‘The measure of tempo maintained in the first bar is maintained in every bar that follows, by reason, that one doesn’t take more time for one bar than for another.

‘We give this advice to new players, that they basically count by semi-Tactus [minims] … and this way they cannot fail to play in Tactus with all the rigour that is required. because by experience we see that those who don’t play in Tactus err in the semi-Tactus.’

Note that Tomas is encouraging beginners to count relatively quickly, in minims [about MM 60], whereas more experienced players might count the whole Tactus [semibreve ~ MM30]. Modern-day musicians are so used to a fast count, that even Tomas’ easy option of 60 bpm is challengingly slow for many nowadays

.

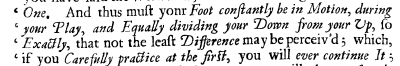

‘If you want to maintain Tactus and semi-Tactus well, practise a lot maintaining it for yourself [i.e. within your own body] with the hand and with the foot… for players, maintain Tactus & semi-Tactus with your foot, since whilst playing you can’t do it with your hand.’

Mensuration signs & note-values

Part 1, Chapter 6 De las figuras

‘We are discussing the figuras – written notes – according to their note-value sung in compasete [indicated by C, modern ‘common time’], which is now commonly used by everyone…. even though [C-slash, modern ‘alla breve’] is also called compasete by many, which if taken strictly we would have to sing by whole compas [down-up Tactus, and also bar-length], which is breve or two semibreves. Nevertheless we use it [in the same way] as C, a half-circle without the slash, with the result that using one or the other [mensuration sign, ‘time signature’] we now sing in compasete. What is strictly called compasete in this period, which is C without slash… the Semibreve is one compas [down-up Tactus, and also bar-length]’

So by Tomas’ time, the strict definition of compasete (Milán calls it by another dimunuitive, compasillo) as C is informally extended by many to include C-slash; and the realisation of C-slash strictly according to theory, i.e. counting by breve and semibreve (which would suggest double tempo, though Tomas does not clarify this explicitly), seems to have been abandoned in practice.

Bar-length

Although period use of the term compas often includes the meaning ‘a bar of notated music’, Tomas’ basic explanation of note-lengths clearly shows that bar-lengths can be varied in practice. In his table, the numbers viii, iv, ii and 1 count the number of Tactus beats.

This defining exemplo shows:

- Bar-lengths are expanded as necessary to accommodate large note-values

- The primary meaning of compas is Tactus (as a duration of time corresponding to the movement of the Tactus-hand)

- Note-values are defined in relation to Tactus

In theory, the relationship depends on mensuration sign, but the theoretical distinction between C and C-slash no longer applies in practice.

- A single mensuration sign (i.e. C) allows varying bar-lengths

This contrasts with the modern use of C as a time signature requiring a consistent bar-length of one semibreve.

- There is no assumption of maintaining duration as bar = bar.

This has implications for triple-metre proportions, which today’s performers sometimes describe as ‘bar=bar’. That might be an accurate description in some circumstances, but ‘bar = bar’ is not a period principle that can be used to determine proportions.

Tomas’ (1565) principles of rhythmic notation are entirely consistent with Milan’s theory and practice in El maestro, three decades earlier.

The fundamental quantity is Tactus. Relative durations are specified by note-lengths. The notated bar-length framed by bar-lines is essentially a visual convenience, no more.

Two Principal Requirements for singing from staff notation

Dos cosas se reguieren principalmente para saber cantar canto de Organo.

- Give each note its written time-value

- Know which note is on the up- or down-beat, and which is not

For minims it’s easy… with each beat down or up, you sing a minim… if one minim comes with the downbeat, the next is with the upbeat and vice versa.

Tomas now gives examples for various note-values of how notation is linked to Tactus beats.

8 conditions for playing with total perfection and beauty

Book 1, Chapter 13 ‘So that all music might have that grace and essence (ser – literally, ‘being’) which it deserves, it’s necessary to play with all the delicacy that is required, which is repaid in much gold and creates yet more essence and grace. Without this, all that is played, however good it might be, will not have grace nor brilliance. Here is the clear difference between the same work played by a perfect and refined player, or played by another, imperfect and coarse; because played by the expert it will appear to be delicate and high art, and played inexpertly it seems low-class and coarse, as if it were two different pieces.

‘The conditions which thus beautify the music can be reduced to eight:

- Play in Tactus (compas)

- Place your hands well.

- Strike the keys well.

- Play cleanly and distinctly.

- Let the hands run well up and down the keyboard.

- Use appropriate fingering

- Play with good groove (ayre)

- Make good ornaments and trills (redobles y quiebros)’

‘Playing in Tactus … is the first condition’

For more on Tactus, Tomas refers his readers back to his previous remarks (analysed above).

Chapters 14-18 are specific to keyboard, in particular clavichord, technique. Chapter 14: Fingers are numbered from thumb 1 to little finger 5. Hands are curved like cat’s paws, fingers close together, thumb underneath and close to the 5th finger. All this is close to period harp-technique too. Elbows are dropped, relaxed and close to the body.

Chapter 15: strike the keys with the flesh of the finger; with impetus; equally strongly with both hands; don’t strike from too high above the key; press down into the key, but not so much as to raise the pitch; don’t raise the fingers too much away from the keys.

Chapter 16: for clarity, release one key before playing the next. Lift the finger a little after playing, but don’t take them too far away from the keys.

Chapter 17: for facility throughout the whole range, keep the hand compact, turn the hand slightly in the direction of movement (especially for fast notes), keep the active fingers close to the keys.

Chapter 18 defines Principal Fingers as those that strike the first note of trills. Thumbs are not used for black notes, except for octaves in one hand, or when there is no possible alternative. One should not use the same finger twice in succession for crotchets or (especially) quavers. Consecutive semibreves, on the contrary, are played with one finger repeating. Melodic crotchets are taken pair-wise, alternating two fingers. This is the familiar Renaissance concept of Good and Bad notes, corresponding to the accented and unaccented syllables of a song-text: more on Good & Bad here. Quavers and semiquavers are fingered four-by-four.

Tomas analyses fingering in considerable detail, confirming the importance of fingering in creating short-term phrasing and articulation. His fingerings for two-note chords require changing fingering on consecutive thirds, which has implications for facilitating particular ornaments (page 45).

Groove and Swing

Chapter 19 introduces the concept of ayre – particular ways to apply rhythmic freedom to fast notes, within the regular pulse of the Tactus. Ayre sometimes refers to melodic tunefulness, but more often to subtle rhythmic patterning. Depending on context, I translate it as ‘groove’ (dance patterns and/or medium- term patterning) or ‘swing’ (changeable, short term patterns), in the jazz sense of subtle rhythmic adjustments that give a particular character or elegant shape without disturbing the fundamental beat.

‘The way to play with good ayre… requires playing the Crotchets in one way [groove] and the Quavers in three [alternative options for three different ways to swing].’ Thus these adjustments are within the fundamental steady pulse of Tactus (semibreve, down-up) and semi-Tactus (minim, down or up).

‘The manner – manera – you must have for playing Crotchets is to wait – detenerse – on the first and hurry – correr – the second; and neither more nor less wait on the third and hurry the fourth; and in this way for all the Crotchets. As if the first Crotchet were dotted, and the second a Quaver… and take note that the Crotchet that hurries should not be very hurried, but a little moderate – un poco moderada.

‘Of the three manners of [playing] Quavers, two are done almost the same way, which is waiting on one quaver and hurrying the other one… In one manner you begin by waiting on the first Quaver, hurrying the second; and neither more nor less waiting on the third and hurrying the fourth; and in this way all of them… As if the first were dotted and the second a Semiquaver. This manner is suitable for works that are contrapuntal throughout – todas de contrapunto – and for passages of decorative fast notes both long and short – passos largos y cortos de glosas.

The second manner is done by hurrying the first Quaver and waiting on the second; and neither more nor less hurrying the third and waiting on the fourth; and in this way all of them… As if the first were a Semiquaver and the second a dotted Quaver. In this manner, the dotted Quavers are never on the beat, but in-between. This manner is suitable for short decorations – glosas cortas – which are done like this in [composed, contrapuntal] works as well as in [improvised] fantasia. And note that this manner is very much more galana (elegant, showy) than the other one, above.’

The noun gala and its related adjective galana occupy an area of meaning that extends from ‘decorative’ or ‘elegant’ to ‘luxury’ or ‘ostentation’. Milán discusses tañer de gala, which seems to be well towards the ‘showy’ end of this semantic spectrum, as suggested by my translation ‘bravura playing’. More on Milán here.

‘The third manner is done by hurrying three Quavers and waiting on the fourth; and be warned that the waiting has to be all the time that is necessary so that the fifth Quaver comes to be struck in time on the semi-Tactus; and in this way all of them. With the result that they go four by four… as if the three Quavers were Semiquavers and the fourth a dotted Quaver. This third manner is the most galana of all, and is suitable for long and short decorations – glosas largas y cortas.

‘Take note that the waiting on the Quavers should not be much, but just enough to show and be understood a little, because waiting a lot causes great gracelessness and ugliness – desgracia y fealdad – in the music. And similarly for the same reason, the three Quavers that hurry should not hurry too much, but with moderation, conforming to the waiting on the fourth Quaver.

The soundscape of Renaissance rhythm

Tomas’ instructions for Renaissance ayre create a rhythmic soundscape that differs sharply from 20th-century assumptions about art-music and improvisatory fantasias. He demands that the player count in minims, which should be completely steady. From other evidence, it is plausible that this count would be somewhere around minim = 60. Within that slow steady beat, crotchets are good/bad (i.e. subtly long/short), quavers are subtly shaped in one of three specific ways, the choice depending on the genre of music and the length of the decorative passagework. Whichever groove or swing is applied, it is maintained consistently throughout the passage in question.

There is no trace of 20th-century rubato, nor of its early-music derivative, phrasing that ‘goes towards’ a certain point. There is none of the hesitancy and pauses that often characterise modern-day performances of ‘improvisatory’ music: on the contrary, even if the player is genuinely improvising, Tomas and his advisers, the Cabezon brothers (as well as Luys Milán before them) expect Tactus, Groove and Swing to be maintained.

Nowadays, one might describe Tomas’ sound-world as steady pulse at approximately 60 bpm, with regular groove at the subordinate level around 120 bpm, and various options for swing at the most rapid level of rhyhmic activity, around 240 bpm. But in that pre-Newtonian age, Tomas has no concept of Absolute Time on which to base such a description; he has no clock precise enough to measure such short durations: rather, he has Tactus, which counts Aristotelean Time as ‘a number of movement in respect of before and after’ (Aristotle, Physics). The essential quality of that Tactus movement is that it is consistent – within the limits of human perception – so that Tomas’ minim is always about one second in duration (though he has no machine to measure it, and no conceptual framework for comparing it to anything more objective than his own feeling of consistency).

It is this essential consistency that allows Tomas to map specific performance practice instructions onto particular note-values (minims are steady, crotchets groove good/bad, quavers swing in one of three ways). Such linkage, which is seen also in Ortiz’s instructions for viola da gamba, strongly implies that the absolute duration in time of any given note-value is approximately fixed within the whole repertoire: e.g. minims are approximately one second. If the durations of note-values could vary arbitrarily (as they can in modern practice), this linkage would be meaningless.

Nevertheless, Milan indicates subtle changes in tempo from one piece to another, centred on a default tempo of ‘well measured Tactus’ that is ‘neither very fast nor very slow’. But these changes are not imposed arbitrarily by performers’ artistic choice: performers are required to follow the composer’s directions. So – in contrast to the 20th-century concept of ‘artistic freedom’ for performers, the period attitude is that there is a correct tempo, and that it is the performers’ job to find it.

Ornamentation 1: Graces

Chapter 20: How to make redobles and quiebros

Summarising Tomas’ definitions & examples: Redoble is a reiterated upper-note trill, starting on the written note, and turned at the beginning.

Quiebro is an upper- or lower-note trill, starting on the written note, but without initial turn. Quiebros can be senzillos (simple, i.e. one flip) or reyterados (reiterated).

The difference between redoble and quiebro is that the redoble has the initial turn through its lower note.

‘Redobles are only made on complete bars, i.e. on Semibreves. And Quiebros are made on MInims and on Crotchets and, as a marvel, on Quavers. Reiterated quiebros are made on Minims, simple quiebros on Crotchets; except for one which is not reiterated, and always made on Minims on the [hexachord] pitches sol fa mi fa. This is called the Quiebro de Minima.

‘Reiterated quiebros are made on every Minim where the fingering permits. But simple ones are not made on every Crotchet, but alternately yes and no.

‘There is only one way to make Redoble … with whole-tone and semitone combined. Quiebros are made with tone or semitone, except for the Quiebro de Minima, which is always made … with the lower semitone and upper tone. The other way would produce gracelessness and displeasure – desgracia y desabrimiento – to the ears, for which reason it must not be made where it would finish on mi…. But it can finish on any other note ut, re, fa, sol, la.

Redobles can have the semitone above or below, ‘but note that in no way is it permitted to make a Redoble with two whole-tones combined, because this is very graceless and displeasing to the ear.’

Redobles permitted and prohibited

Tomas gives specific fingerings for each ornament, for the keyboard, left and right hands.

‘These styles of redobles and quiebros … are very new and very elegant – galanos – causing such grace and tunefulness – melodia – in the music, which bears them in so many degrees – grados – and with such contentment to the ears, that it seems something quite different from playing without them, so much so that there is every reason to use them always, and not others which are old-fashioned and not graceful.

‘Simple quiebros … for ascending are made with tone or semitone below. Those for descending are made with tone or semitone above.’

Tomas describes a very fast ornament, in which the principal note is not actually repeated, but sustained whilst the auxiliary is played almost simultaneously and quickly released. There is no conventional notation for this technique (described also in some harp sources), so he does not provide an example. With this type of fast mordent, Tomas prefers the descending version (with upper auxiliary) to the little-used ascending version.

Quiebros on Crotchets, both ascending and descending, are sometimes made on the beat, and sometimes on the off-beat, and this [on the off-beat] is the better and more elegant – galana – manner, because it gives more grace to what is played.

Tomas gives keyboard fingerings for each option, for each hand.

The upper-auxiliary Minim quiebro normally used for descending can be used ascending if the principal note is a mi.

‘Sometimes, and only descending, one can make quiebros on two consecutive Crotchets. which is done for grace and elegance. This occurs when after an ascent to a Semibreve there are two Crotchets descending.

‘When there are ascending Crotchets which then descend, one must always make a quiebro on the highest note, which is done for descending [upper auxiliary]’ ‘Similarly, when there are descending Crotchets which then ascend, one must always make a quiebro on the lowest note, which is done for ascending [lower auxiliary].

‘Similarly, to give more grace to the music, one must always make quiebros on every Crotchet that follows immediately after a dotted Minim.’

‘So that the music should have more grace and thus give more contentment to the ears, it’s necessary that redobles and quiebros de minimas should be done by either hand, a redoble with one hand, another redoble with the other; and similarly a quiebro with one hand, another quiebro with the other; responding to each other.’ The fingerings for consecutive thirds (above) facilitate a similar effect between two voices in one hand. ‘This is heard when both hands play Semibreves or Minims which can have redobles or quiebros, playing them one after another, which greatly adorns the music and gives it grace, especially when there is a chain of Semibreves or Minims.’

‘When the Mode – tono – avoids certain notes … the ornaments should also avoid them.’

Tomas gives technical advice for executing ornaments at the keyboard, repeating his earlier comments about keeping the fingers close to the keys. That advice might well be adapted for vihuela and harp, as keeping the fingers close to the strings.

Tomas characterises his ornamentation as ‘new’, and it is intended for the relatively short sustain of the clavichord. Fewer, or different ornaments might be appropriate to Milán’s period and/or to other instruments. Nevertheless, it seems likely that all renaissance music was ornamented considerably more than the raw notation suggests.

Tomas demands almost ceaseless ornamentation, more-or-less on every second note, as well as strict adherence to rules of ‘grammar’ for ornamentation. Such florid playing in regular Tactus, and with the groove and swing of ayre, creates a sound-world for the late 16th century that contrasts notably with 20th-century assumptions about art-music, the ‘purity’ of polyphony and what ‘improvisatory’ playing might mean.

Setting polyphonic works

Chapter 20. ‘Playing polyphonic works on the clavichord is the font and origin from which are born and proceed all the fruits and benefits, and all the art of playing for players.’

‘It should be noted that in whatever work of any kind, all the voices are interdependent and linked one to another, that no individual voice can move a single note without having specific respect and regard for all the other voices. And similarly voices are measured and counted, linking voices Tactus by Tactus, semi-Tactus by semi-Tactus.’

‘Two things have to be kept with all rigour, which rule and govern the arranger so that they never err: these are count and measure, which are interdependent… Measure is the same as compas (Tactus, also bar-length), by which all practical Music is ruled and governed.’

Tomas also explains vihuela tablature, and how to set polyphonic works for vihuela.

Tips for understanding polyphonic works

Chapter 21. ‘Brief advice for new players to master quickly any kind of work’

‘Three things are necessary to understanding any kind of work quickly, and thus to play it more perfectly.

1. Play in Tactus

‘maintaining it always with the same equality of time, i.e. not changing it from more to less nor from less to more. For this, it’s necessary to maintain Tactus with the foot and similarly to take great care with the semi-Tactus… in addition, it’s necessary to understand note-values and give each of them their full duration.’

2. Sing through each individual voice in turn

3. Understand all the Consonances and Dissonances in the work, whether in 2, 3 or 4 voices.

How to obtain benefit from studying polyphonic works

Chapter 22. ‘Five things have to be noted:

1. Understand profoundly the invention and artfulness in the contrapuntal progressions – passos – whether the response or repeat is at the fourth, fifth, octave or other interval… in two, three, four or more voices; with or without imitation. The Art of Fantasia consists of all this, which above all one has to get to know; because in everything it is only arte [i.e. a coherent system of rules] that makes a Master. And from that it follows that all those who ignore the rules are imperfect.

2. Note the entrance of each voice, to know if it enters before the cadence, in the cadence, or after the cadence; with what invention or subject it enters; for the entry of each voice is the most delicate matter, of greatest subtlety and arte that there is in music. So this must receive great attention and care, in order to apply it in the works.’

3. Note all the styles of Cadences which are used in the works, undersanding them profoundly and memorising them, in order to make similar cadences when improvising [fantasia].

4. Note all the Consonances and Dissonances… and memorise them, in order to create varied progressions, for this is of great benefit in acheiving flow and abundance of spontaneity [fantasia].

5. When a progression is repeated, note the differences in the repeated version, whether in 2, 3 or 4 voices.

‘For new students to apply these benefits in improvisation – fantasia – it’s necessary that they practise constantly with the same progressions that they have learnt, so that with this practice – uso – they become accustomed to the [rules of] arte, and then they can easily play other progressions. Similarly, it is very advantageous to transpose a particular progression into all possible keys. For this, take note that wherever you want to transpose them, they must keep the same [Hexachord] solmization.

‘To gain the great fruits and benefit for improvising of all the above, it’s necessary to practise many times each day, with great perseverance, never mindlessly – desconsiando – but trusting for certain that work and constant practice – uso – conquers all and creates a maestro… A drop of water can carve out stone, not in one or two droplets, but falling constantly.’

Tomas recommends frequent, mindful practice, repeating the same material many times in order to perfect, memorise and internalise it. Although his comments are consistent with the modern-day understanding of learning elite skills, he expresses himself through the period meaning of such terms as uso (practical techniques) and arte (a coherent set of rules for effective creativity). What we mean nowadays by ‘art’, the ineffable mystery of the emotional power of music, is Renaissance Science. More about period terminology here and here.

Tomas’ emphasis on learning progressions and cadences echoes the approach of Milán’s El Maestro.

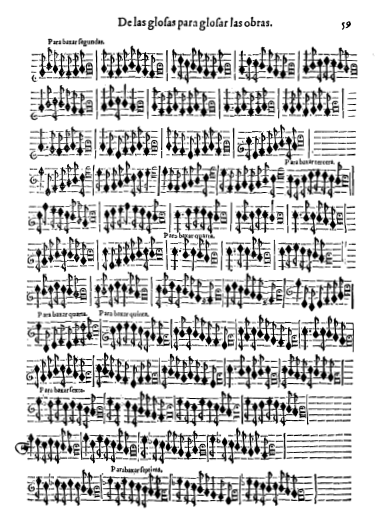

Ornamentation 2: Divisions

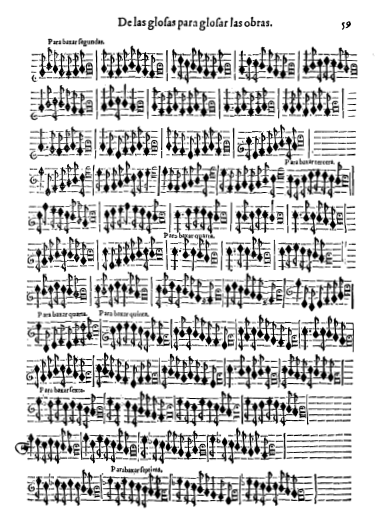

How to add divisions to polyphonic works. Chapter 23 Del glosar las obras

Renaissance ornamentation is categorised as Graces on a single note (the redobles and quiebros discussed above) and Divisions or Diminuitions – glosas – where the interval between two long notes is ‘divided’ into many shorter notes. Tomas gives several examples for each interval, ascending and descending.

‘To add divisions – glosar – to polyphonic works one must be advised that glosas are only made on three note-values – Semibreves, Minims and Crotchets – even so, least often on Crotchets.

‘To glosar a work well, there are two things to note:

- All the voices should have equal amounts of glosas

- If the voices repeat something, the glosas are also repeated in all the voices

unless something prevents this, which is often the case.

If it is necessary to glosar Crotchets ascending or descending [four by four, stepwise], one must take the glosas for Semibreves ascending or descending a fifth.

Helpful Hints & Improvisation

Book 2, Chapter 52. Useful advice for new players.

Tomas’ purpose is not only to teach the instrument and basic musicianship, he also gives advice on how to learn to improvise within the demanding style of 4-voice Renaissance polyphony.

1. Practise running the hands throughout the whole range of the instrument, with appropriate fingerings, observing all the conditions and circumstances already discussed.

2. Practise making redobles and quiebros with both hands.

3. Maintain Tactus very well with hand or foot… give each note-value its precise value

4. After studying a piece well in a class, write it out just as the master taught it, with the glosas etc. Similarly, sing through each individual voice.

5. Understand well how to play the instrument

6. Take as your foundation and guide the Eight Conditions for playing perfectly [above].

7. Understand and be able to play in all possible keys

8. Practise easy works first, and then progressively more difficult ones

9. Practise transposing works into every possible key.

Similarly, try to take from each work those progressions which have graceful melodies, and memorise them, so that afterwards you can improvise on them spontaneously.

Once you are expert in all these things, try to start to play improvisations, based on some melodious progressions. In addition, try to play the progressions with different imitative counterpoints – fugas – i.e. at the fourth, fifth and octave, which greatly beautifies the music.

Similarly, try taking one voice from a work (whichever you want, soprano, alto, tenor or bass), and play it as the treble in four-voice harmony, making up three voices in your head… with a variety of harmonies, which greatly exalts and beautifies the music.

Similarly, once you are already a little expert in playing a given voice like this as the treble, trying playing it as the alto, tenor or bass [with three new voices created around it]. This suggests the Renaissance technique of composing a Parody Mass, in which the counterpoint of a pre-extant motet is re-worked and greatly extended to create an entire mass setting. This technique could be a model for improvisation in Tomas’ style, as could the fantasias compiled for keyboard, harp and vihuela by Henestrosa, ‘cutting and pasting’ contrapuntal progressions from various works into a new creation.

If you want to be a perfect player, try to apply yourself and practise little by little, playing counterpoint that has a good feeling – ayre – and graceful melody; on plainchant; and especially polyphonic music, until you are perfect at it. For this is the root and source from which grow and proceed all the skills applicable to the keyboard, and also the perfection and grace which it gives to all the music that is played.’

Tomas final words perfectly capture the essence of Renaissance improvisation: Practise by playing good music well; strive for total perfection; this will improve your skills, your improvisation and your playing of written music.

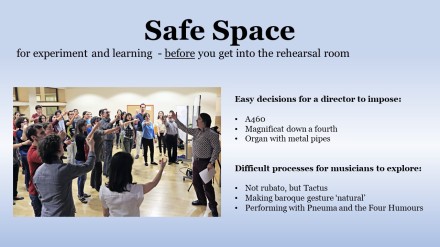

Modern-day performance

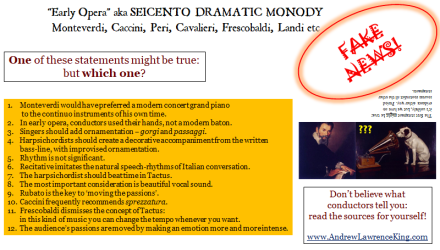

Three significant differences stand out from Tomas’ rules of arte, when compared to today’s HIP approach to fantasia and renaissance polyphony.

- Many modern-day performers choose not to play in rhythm.

- Few modern-day performers add much ornamentation.

- Few modern-day improvisers maintain correct counterpoint to Tomas’ standards.

Tomas’ comments on Tactus are so strongly worded that it is beyond any doubt that all the music of this period should be played in Tactus, counting regularly on a minim beat, and controlling this with the physical movement of hand or foot. Unless you frequently practise and problem-solve with a physical Tactus-beat, you are out of touch (sic) with Renaissance rhythm.

This insistence on Tactus is certainly fundamental, but it is not merely elementary. On the contrary, Tomas associates it with ‘a perfect and refined … expert’, and with playing that is ‘delicate and high art’.

The amount and detail of ornamentation specified by Tomas is alarming for those of us accustomed to ‘the pure lines of renaissance polyphony’. Our ears, as well as our fingers, will need plenty of practice with so many redobles, quiebros and glosas in all the voices, on almost every second note.

We might assume that improvisation excuses sloppy rhythm and bad counterpoint, even that ‘art has no rules’: Tomas’ book exists to teach the contrary!