At the seaward end of Barcelona’s Ramblas, Colombus points the way not only to America, but also towards good Baroque Gesture: weight on the back foot, front leg elegantly bent (more about historical posture here). Head erect, eyes focused in coordination with a strong pointing gesture, other fingers held in by the thumb (as shown by Bulwer, see below). The arm is not locked straight, but has a nice curve at the elbow, the shoulders are nicely dropped, the left hand lower than the right and relaxed.

Notice that he holds his music/script in his left hand, leaving the right hand free to gesture. The Historical Action workshop is THIS way!

This is the third in a series of posts on Historical Action and Baroque Gesture, following on from Start Here: How to study and How to Act: Preliminary Exercises. For this post, I will use examples from Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607): the first edition (1609) is here, together with the second (1615) print, which corrects some errors from 1609 but also introduces new mistakes.

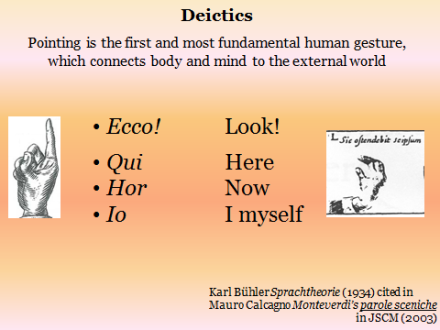

In an excellent article on Monteverdi’s parole sceniche for the journal of the Society of Seventeenth-Century music here, Mauro Calcagno studies text/music relationships in Orfeo from the perspective of Deixis, the “pointing” function of language analysed in Karl Bühler’s 1934 Sprachtheorie. Die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache. Bühler is translated into English as Theory of Language. The Representational Function of Language, trans. Donald Fraser Goodwin (Amsterdam-Philadelphia: J. Benjamins, 1990).

Deictics are words that indicate person, time and place. They are prominent in Striggio’s libretto for Orfeo and, Calcagno argues, are musically highlighted by Monteverdi. Deixis (Greek) or demonstratio (Latin) can be

- Spatial: this, that, here, there

- Temporal: now, then

- Personal: I, you, my, yours

Three deictics are quite literally central in space-time and for each character personated: here, now, I

Pointing is the first and most fundamental human gesture,

which connects body and mind to the external world

In the theatre, pointing gestures connect the actor’s body with the spectators’ minds, and create a illusion of a mind/body connection with the imaginary world of the drama. Perhaps for this reason, early opera libretti often include visual descriptions that correspond with the real-life external world, just outside the theatre. Pointing to queste rive ‘these shores’ in lakeside Mantua takes poetic imagery and visions of the dramatic scene conjured up in actors’ and audience’s minds, and connects those imaginary visions to an external world that the courtiers knew as real and close at hand.

Renaissance Enargeia (the emotional power of detailed visual description) was often energised (Energia is the spirit of passion communicated via the eyes) by the powerful word Ecco (look!).

Calcagno introduces his argument with a discussion of oratory, and briefly mentions the link between pointing words and physical gestures. He then demonstrates the prominence of deictics in Striggio’s libretto, and points out the significance of deictics in Monteverdi’s musical setting. Around 1600, gesture was a key element of oratory, of rhetorical delivery. We can therefore be confident that pointing gestures should be a prominent and significant part of the Historical Action. Prominent, in that there will be many pointing gestures, and audiences should notice them. Significant, in that these pointing gestures should carry meaning and weight, so that the imaginary vision is convincing.

According to Quintilian, it is these visiones – ‘fantastic… daydreams… whereby things absent are presented to our imagination with such extreme vividness that they seem actually to be before our very eyes’ – that move the audience’s passions. Calcagno shows that Deictics draw attention to movement, physical movement across the stage and within the imaginary field of view of the dramatic scene, and the to-and-fro of emotional communication between actor and audience. Deictic words connect with pointing gestures to create visiones and muovere gli affetti (to move the passions).

So it is no surprise that John Bulwer’s (1644) survey of gesture, Chironomia, includes many pointing gestures. In my approach to Historical Action, I encourage actors to begin with these simple but powerful gestures, not only because they are so prominent and significant in circa-1600 theatre, but also because pointing is

the first and most fundamental human gesture, which connects body and mind

There are two challenges for modern-day performers of Baroque Gesture. One is to root a historical gesture in the full-body structure (that body-structure founded on period posture of course): otherwise the gesture seems disembodied. The other is to connect each specific gesture to the concept in mind (inspired by each word of the text, in real time): otherwise the gesture seems mindless. The difficulty is that learning unfamiliar gestures from a historical treatise tends to focus attention on the arm and hand, disconnecting the gesture from body and mind. This misplaced attention on the gesture itself, rather than on the embodied action and mental vision it signs, is a potential danger for actors and spectators alike.

Training Exercise for Pointing Gestures

The remedy is to connect each gesture to body and mind. The exercises in my two previous articles are designed to wire-up connections to posture and text, ready to empower the pointing gestures below. Pointing is indeed a fundamental, instinctive action, so once a specific hand-shape has been learnt, an excellent way for a training partner or rehearsal coach to call forth a well-connected gesture is to ask (with assumed innocence):

Where is that?

When is that?

Who is that?

as appropriate, for Spatial, Temporal or Personal deictics.

If you can make the question seem spontaneous, it has a good chance of triggering a spontaneous response from the actor, who will point with a gesture that is both historical and also mind/body connected. The observer should now check for technical errors in the historicity of the gesture (too high, too low, wrong hand-shape) or for tell-tale signs of lack of connection (gesture looks weak, eyes are not appropriately directed and focused, gesture seems ‘artificial’, wrong timing of eye-movement and hand-gesture) and give feedback.

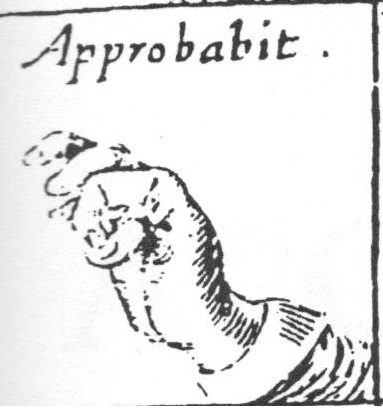

If the actor did well, the observer should say so, and add a gesture of approval, why not!. After all, if we believe that baroque gestures can move the passions, then shouldn’t we use them in real life too? Or at least, in that transitional space between real life and dramatic fantasy, the rehearsal room!

Pointing gestures in Monteverdi’s Orfeo

As Calcagno points out (did you get that?), Deictics are prominent right from the beginning of the Prologue. “Striggio strategically places the three most primitive deictics (Io, qui[nci], and ora) at the beginning of strophes 2 to 5. But the first strophe also emphasizes the function of the “pointing words.” The deictics mio and voi, appearing in the first line … [establish] a channel of communication with the public.”

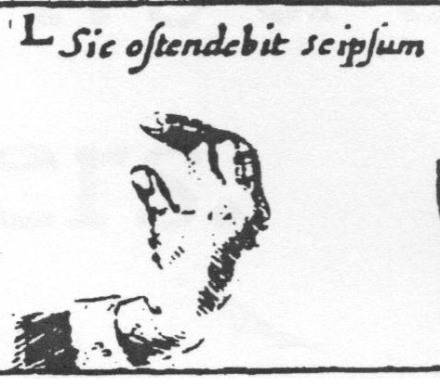

In that very first line, Monteverdi extends the word mio (my) for more than one second, giving time and prominence to the significant ‘refer to self’ pointing gesture.

This is how to refer to oneself

As we would expect, this fundamental and central gesture is seen frequently in period iconography and in modern-day life.

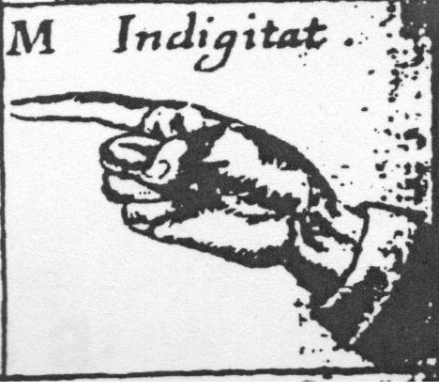

‘From MY beloved Permesso’ a VOI ne vegno ‘to YOU I come’, La Musica continues. ‘You’ refers to the audience, ‘great heroes, noble blood of Kings’. To point directly with the index finger would not show the respect such an audience deserves; a more elegant pointing gesture is required.

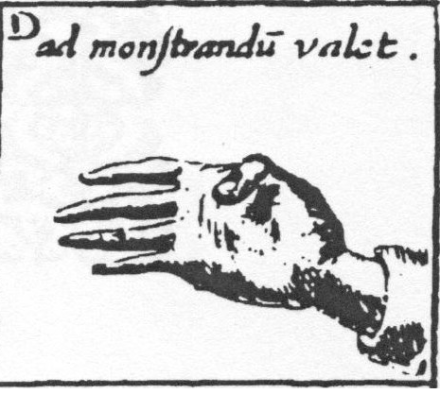

Bulwer shows a gesture ‘suitable for pointing’, which is a simple variation on the Default Gesture studied in the first article of this series, here. Starting with your hand in the default rest position, close to the body and between chest and belly, middle two fingers together, little finger curved in, index curved out somewhat…

let the thumb fall into the hand slightly, in order to give slightly more prominence to the extended index finger. Now extend your arm outwards, in an elegant pointing gesture. You could time the Stroke of this gesture to give added significance to ‘you’ or to the movement of ‘I come’: try both options. A voi ne vegno.

Contrary to Dene Barnett and other directors who have actors learn a fixed ‘choreography’ of gesture for each speech, I believe strongly that some element of improvisation can be of great help in giving performers a sense of ‘ownership’ of the gestures they make, in connecting the gesture more securely to the actor’s body and to a mental vision of the text. Yes, improvisation does entail the danger of a loss of historicity in precise details of the gesture, but I consider that the gain in credibility far outweighs the risk. And ‘improvisation’ need not be a daunting challenge: a good first step is to give the actor a spontaneous choice between two well rehearsed options, as with the two options for timing the gesture described above.

Bulwer’s Ad Monstrandum way of pointing is also convenient when you want to indicate a wider field of reference, for which the direct point with the index finger would be too narrowly focused. So you can use this pointing hand to indicate an area of the dramatic scene – in queste rive (on these shores) – an extended interval of time – in questo lieto e fortunato giorno (on this happy and auspicious day) – or a group of people – Muse, honor di parnasso (Muses, honour of Parnassus). In the Prologue, gestures connected La Musica and the audience. In Act I, the to-and-fro words discussed by Calcagno call forth gestures that connect musicians (the Muses have cetre sonore, sonorous lyres) and singers (sia il NOSTRO canto al VOSTRO suon concorde, may OUR song and YOUR instrumental sound meet in concord).

But I have a minor disagreement with one detail of Calcagno’s article. Simple logic and the theatrical necessities of the original production with just a few singers dictate that it is the actors who are singing and the musicians who represent the muses with their instruments. Nostro and vostro must be this way around (the music editions and printed libretti are inconsistent). As proof, the 1609 print calls for an string-ensemble suono of a 5-part violin-band, violone, 3 theorboes and harp: presumably these represent Apollo (harp) with the 9 muses.

(In this scene we also see a very small flute, representing the earthly Shepherds’ response to the Muses’s Music of the Spheres, and hear two harpsichords, ‘rude mechanicals’ [Shakespeare] that perform the practical function of ‘guiding and supporting the whole ensemble of instruments and voices’ [Agazzari 1608], since there was no visible Tactus-beating in theatrical music, and certainly no modern conducting in the 17th-century.)

This small point of difference (got it?) with Calcagno illustrates a vital rule for pointing gestures. You have to know what you are pointing at. This calls for some decisions, which should ideally be consistent for the whole production. Where is the temple? Where are the woods? Who are the Muses? Which way leads to Hell? A vaguely outstretched arm pointing at nothing in particular shows a disconnect between mind and body that will undermine any attempt to move the audience’s passions.

So whilst there is room for academic debate about vostro and nostro in this phrase, on stage a decision needs to be made. All the actors and musicians involved need to know who’s who, and where’s what, so that they can point with confidence and conviction.

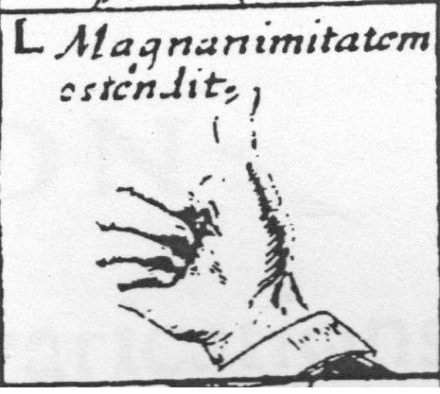

Another way of pointing seems to show an elegant casualness, a sprezzatura in gesture, by pointing with the thumb.

This is convenient for pointing to the right side or behind, less suited for something central or left. Bulwer classes this as a Rhetorical (rather than ‘natural’) gesture, but his only comment is that this ‘act of Demonstration’ is a ‘received custom’.

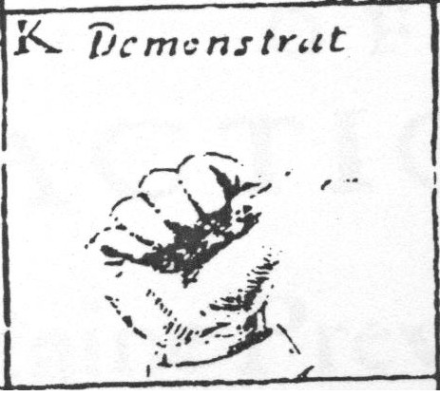

As a Rhetorical gesture, the pointing index finger is ‘most demonstrative’. If the other fingers are compressed in by the thumb, ‘and the Index displayed in full length’ this gesture ‘upbraides’ (reprimands, rebukes, scolds).

For more respectful pointing, the turned-over default position of the hand should be used, with the index still slightly curved, and the other fingers not held in too much. In this way, Art refines a Natural gesture into the elegance that we observe in period iconography.

Pointing gestures become stronger as the arm is extended more. This extends the gesture for more distant objects (on stage, or imagined as part of the envisioned scene), or makes the gesture more forceful for an object in the middle distance. Nearly always, the arm remains somewhat bent, as if it remains relaxed in its own weight whilst being lifted from the wrist. A rigid, straight arm lacks elegance.

As the speaker points, fellow-actors may well react by pointing too. At any time, non-speaking actors may also point to the speaker, or to the object under discussion. Many period paintings show pointing gestures of all kinds, and it’s well worth studying and imitating these. Notice the long-range and short-range pointing in Caravaggio’s St Matthew.

In Rhetoric, the index finger pointing downwards (with the rest of the hand as a fist) is very strong, used to ‘urge’ and ‘drive the point into the heads’ of the listeners. It might be used for an emphatic ‘here’ or ‘now’.

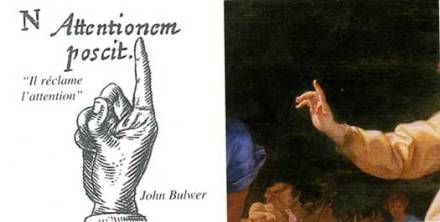

The index finger pointing upwards is a most useful gesture, calling for the audience’s Attention. The same principles apply: the gesture is strengthened by compressing in the other fingers and by extending the arm; it is made more elegant by retaining some curvature in fingers and arm. The emotional power of visual detail, the force of Enargeia is often invoked with Ecco! (behold, look): this attracts the listeners attention, which can then be directed to the object of discussion with one or other pointing gesture.

An upward pointing gesture is also called for if the text mentions God or Heaven (as seicento texts often do). This is one of the exceptions to the general rule of decorous gesture that the hand should not rise higher than the shoulder. Here Régnier demonstrates the divine inspiration of Music: the arm is strongly extended, yet elegantly curved.

Pointing can be a convenient way to start using baroque gesture in rehearsal and performance. The actual movements are quite intuitive, so there is less chance of getting distracted by the mechanics of the gesture and ‘losing sight’ of the significance of the text. Neither the actor nor the audience should be looking at the pointing arm, attention should be fixed on what is being pointed out. Pointing is indeed a fundamental gesture, but it is not necessarily simple. A good pointing gesture will be rooted in whole-body posture, and will recruit the face and (especially) the eyes.

As Bühler reminds us, pointing words connect the speaker to the object under discussion. A pointing gesture does not merely show what the actor is talking about, it also demonstrates the nature of the relationship between pointer and object.

Consider how the shepherds in Monteverdi’s Orfeo might point at Silvia, as they first recognise her (‘elegant Silvia, the sweetest companion of beautiful Euridice’), as they react in shock to her demeanour (‘Oh, how sad her face is!’), during her narration of Euridice’s death, and as she departs to exile (like an ‘ill-omened bat, hateful to the shepherds and the nymphs’). Period conventions discourage actors from moving around the stage whilst they are singing, so the direction of the shepherds’ pointing might not change at all, but the affetto certainly will. And how will this Messaggiera’s Refer to Self gesture be transformed at the words odiosa a me stessa, ‘hateful to myself’?

Calcagno draws his readers attention to the to-and-fro between actor and audience. Period texts often set up contrasts between stage left and right: “on one hand …. on the other hand”. The historical convention is that anything good is to the actor’s right, everything bad is to the left. This convention dictates the relative positions of the actors on-stage, as well as the imagined locations of everything that is mentioned in the play-text or operatic libretto. The next post in this series, on my Ut Pictura technique for applying historical gesture in modern-day performance, continues from this point…

Click on the pointing hand, or here, to read more.

For now, well done, everyone!

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our websites:

http://www.TheHarpConsort.com [the ensemble, early harps & Early Music]

http://www.IlCorago.com [the production company & Historical Action]

http://www.TheFlow.Zone [Flow for optimal creativity, The Zone for elite performance]

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago. From 2011 to 2015 he was Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions. He is now preparing a translation of Bonifacio’s (1616) Art of Gesture and a book on The Theatre of Dreams: The Science of Historical Action.

Pingback: Understand, enjoy and be moved! Listening to the Rhetoric of Orfeo | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Hand gestures and so much more… | al'arba

Pingback: OPERA OMNIA – Music of the Past for Audiences of the Future | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: How to study Monteverdi’s operatic roles | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Ut pictura: reverse-engineering Baroque gesture | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Modus Agendi, or How to Act: preliminary exercises for Baroque Gesture | Andrew Lawrence-King