Celebrating the European Day of Early Music and the first anniversary of OPERA OMNIA, Academy for Early Opera & Dance, Institute at Moscow State Theatre ‘Natalya Sats’, here is my article presented by Katerina Antonenko at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama’s Reflective Conservatoire conference, which has become perhaps the most significant forum of its kind, for discussing new developments in tertiary music education.

OPERA OMNIA offers a new model for Early Music: linking Research, Training and Performance; connecting Music and Drama; and hosted not by a conservatoire, but by an opera house. We believe this model can be more historical, more accessible, more practical, and more relevant to the 21st century than the standard approach of trying to squeeze historical aesthetics into 19th-cent performance ideals and previous millenium educational structures!

A year ago we founded OPERA OMNIA, creating a formal institution and unified branding for a variety of collaborative projects developed during the previous five years. We link Research, Training and Performance of Early Music, in an evolving model adapted for the opportunities and constraints of cultural life in 21st-century Russia.

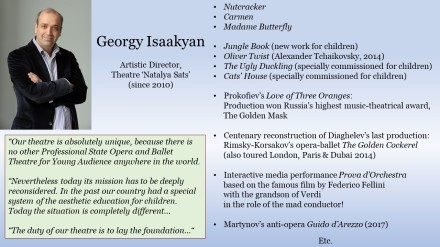

Natalya Sats was founder and director of the Moscow State Children’s Theatre, pioneering Synthesised Theatre, a combination of music and other media. In 1936, she commissioned Prokofiev to write Peter and the Wolf. Statues of characters and instruments from that story adorn the entrance to the present Theatre, built in 1979. Nowadays, her daughter, Roksana continues the Sats tradition of speaking to young audiences before each performance.

The present Artistic Director, Georgiy Isaakyan has extended the programming for young adults and multi-generational audiences: not only family favourites, but also challenging work, including new and early music.

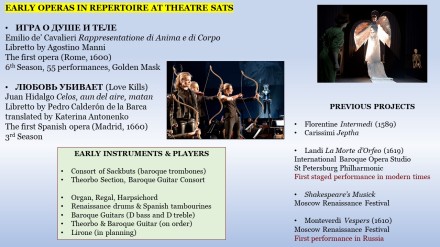

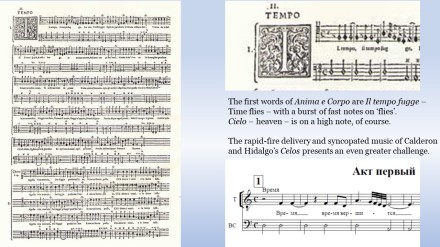

There are two Early Opera productions, both rarely staged today. Celos, the first Spanish opera, is now in its third season. And the very first opera, Anima & Corpo, which won Russia’s highest music-theatrical award, The Golden Mask, has had 55 performances so far.

These two 17th-century operas required collaborations between the Theatre’s resident performers and guests from Moscow’s nascent early music scene. Over the last five years, the Theatre obtained specialist instruments – more are on order and planned for – and in training workshops and performance projects, teams of players acquired the necessary skills.

In cooperation with other institutions, those projects included the first performance in Russia of Monteverdi’s Vespers. More about Vespers here. Each performance was linked to public lectures, advanced masterclasses, academic seminars etc. Continuing performances of Anima & Corpo at Theatre Sats are also a training ground, with new company members each season.

17th-century music requires singers to have both solo and ensemble skills. Polyphonic vocal consorts, 2 or 3 to a part, were a new challenge to singing-actors schooled in the grand Russian tradition. Vocal ensembles in Anima & Corpo are now shared between the Small Choir (a consort of soloists who do most of the dramatic commentary) and members of the Theatre Chorus (who represent a Choir of Angels and swell the numbers to about 80 in the finale.)

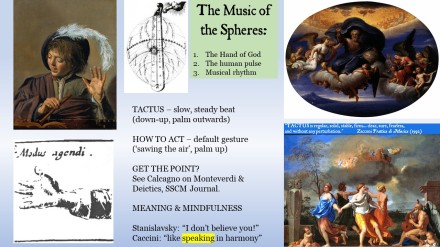

As in Rome in 1600, so in 21st-century OPERA OMNIA: no conductor! Instead, there are multiple Tactus-beaters, relaying a consistent beat between separate groups of performers, so-called cori spezzati. More about Tactus here, and about how to do it here.

Anima & Corpo also provided an opportunity for final-year students from the Russian Institute of Theatrical Arts, who took part in workshops with Lawrence-King and Isaakyan, rehearsed with OPERA OMNIA continuo-players, and performed selected roles alongside professional colleagues in public performances at Theatre Sats. The best graduates were amongst September’s new intake into the professional company.

These performances involving students helped the Theatre reach out to new audience members in their late teens and twenties. But one of the delights of working at Theatre Sats is that we regularly have children, teenagers, and young adults in the audience. The Theatre has front of house staff dedicated to meeting and greeting young visitors, offering informal guidance for individuals, or a short introductory talk for groups.

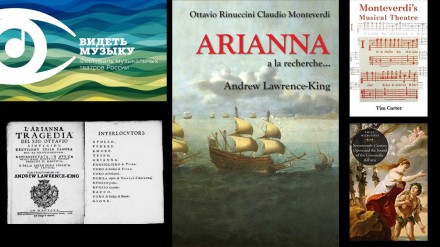

Theatre Sats is also the administrative centre for the annual ВИДЕТЬ МУЗЫКУ (Seeing Music) Festival of the Association of Russian Theatres, which invites to Moscow directors and performers from all around the Russian Federation, uniting an artistic community that spans nine time-zones! The opening ceremonies last September featured an experimental production with historical staging by the young professionals and advanced students of OPERA OMNIA’s International Baroque Opera Studio: Andrew Lawrence-King’s re-make of Monteverdi’s lost masterpiece, Arianna (1608), composed around the surviving Lamento. More about Arianna here.

The astounding visual contrast between the famous Lament scene and the tumultuous arrival of Bacchus immediately afterwards is made audible in Lawrence-King’s work, as the ‘violins and viols’ of the Lament are blown away by ‘hundreds of trumpets, timpani and the raucous cry of horns’. More about how Arianna was re-made, here.

Although most professional ensembles in Europe substitute sackbuts for mid-range and low baroque trumpets, we were able to train up a full consort of natural trumpets, led by guest coach, Mark Bennett.

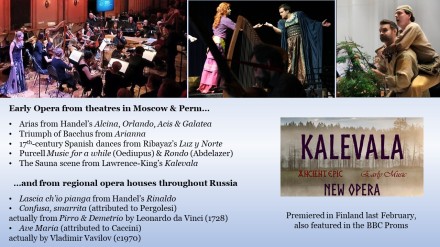

To close the Festival a month later, OPERA OMNIA provided the orchestra for a gala concert of baroque music at the Bolshoy Theatre, bringing together soloists from Sats, other Moscow theatres, and opera houses throughout Russia. This event provided a fascinating snapshot of the state of Baroque Music in mainstream institutions across the nation.

Alongside Moscow’s offering of Handel arias and the Triumph of Bacchus from Arianna, the choices from regional theatres were strongly influenced by mid-20th-century Russian anthologies of baroque favourites: Lascia ch’io pianga of course, but also arias mis-attributed to Pergolesi and Caccini.

We re-edited these, and made a clean ending with the Sauna scene from Lawrence-King’s Kalevala opera.

OPERA OMNIA enjoys close relations with the Moscow Conservatoire, for whom we provide conference speakers and master-classes. We also coach keyboard teachers within the Tchaikovsky School’s program of Continuing Professional Development.

Some of our best Early Music singers were initially trained at the Moscow Choir Academy ‘Papov’, emerging with a good mix of vocal, musical and ensemble skills. Our master-classes also welcome visitors from Stanislavsky, Bolshoy and other mainstream opera houses, singers with excellent voices and rich stage experience, for whom Historically Informed Performance is new territory.

Our production of Celos has led to close collaboration with the Instituto Cervantes, the Spanish embassy and theatres in Spain. We also contribute musically to charitable concerts given by the ensemble of Singing Diplomats at the German embassy.

The rhythmic energy and visual appeal of Spanish baroque has attracted considerable TV and radio exposure, and internet streaming of selected performances.

What remains of the former State education system continues to produce instrumentalists and singers with dazzling virtuosity and rich knowledge of mainstream repertoire. Some baroque aficionados have managed to educate themselves in Early Music with help from visiting teachers, achieving high levels of performance and refreshingly independent academic perspectives. Others studied in Europe, returning to found independent festivals and ensembles in Russia.

With public funding, ensemble Madrigal at the Moscow Philharmonic preserves the style of communist-era Early Music, and Musica Aeterna in Perm brings in most of its players from abroad to play period instruments under a post-modernist baton, but Insula Magica does sterling work in far-off Novo Sibirsk.

In 2012, Theorbo was almost unknown in Moscow. We guided the first generation of theorbists as they transitioned from other instruments.

Video clip of the 2012 premiere of Anima & Corpo here

We are now victims of our own success, in that our theorbists are greatly in demand with other ensembles, so we have had to find a second generation of continuo-players to train up… and this is just how it should be!

Russian theatres have a traditional working practice in which members of the company or orchestra learn repertoire, by sitting-in and observing. We combine that Russian tradition with the baroque concept of apprenticeship.

New-entrant continuo-players begin their studies in a relaxed environment at open workshops. When they reach intermediate standard, they are invited to sit-in and play alongside the professionals at Theatre rehearsals, offering them real-world experience and advanced training on a show which will soon provide them with paid employment.

In the wider arena of the Russian Early Music scene, we measure success not only by absolute standards achieved by young professionals, but also by value added for keen baroque musicians at any level.

The much-debated question of “What is Authenticity?” requires fresh answers in the post-communist oligarchy of modern-day Russia.

In Europe, Performance Practice theories are often circulated by a system of ‘Chinese whispers’, teacher to student, director to musician, CD to listener, and in heated (rather than illuminating) debates on social media. Some performers believe it’s impossible to assimilate enough historical information. Others feel that period practice has been thoroughly worked out, and it’s time to invent something new.

OPERA OMNIA’s message to Russia (and to the wider world) is that HIP is not what some famous person says, nor is it what you hear on your favourite CD! We encourage everyone to check primary sources for themselves – most of the crucial treatises and many original scores are freely available online.

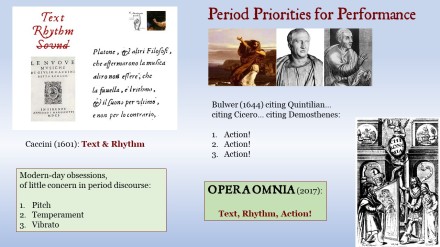

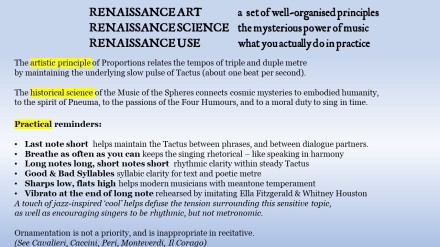

Our take on HIP focuses on practicalities. But before we look for answers, we interrogate period documents for the right questions to ask. Caccini’s (1601) priorities –

Text and Rhythm, with Sound last of all, and not the other way around!

encourage us to look beyond modern-day obsessions with pitch, temperament and vibrato, and far beyond the old-fashioned notion of ‘on period instruments’. More about the Text, Rhythm, Action! project here. The Sats orchestra mixes Early and modern instruments, the training Studio is Baroque only.

Whilst the training Studio works in original languages, the professional Theatre productions of Anima & Corpo and Celos are sung in Russian. Supertitles and printed translations are little used in Russia, and the gain in direct communication between our singing actors and young people in the audience far outweighs the loss of the sound of a foreign language.

We worked very carefully to unite Russian text and Mediterranean music, seeking to achieve natural language, appropriate rhythmic fit, and a perfect match of the word-painting that is so characteristic of this period.

We rehearse the interplay of Text, Rhythm and Meaning with simple but effective hand-exercises, that are themselves fundamental elements of period pedagogy.

In Early Music, Rhythm is directed by Tactus, a slow steady beat symbolically linked to the hand of God turning the cosmos, and to the human pulse.

In an exercise for Text, the hand (now palm up, in the default gesture called ‘how to act’) moves with each accented syllable – Good syllables, in period terminology. More about How to Act here.

We ask singers to think of the meaning of the word, each time they move their hand. Leading questions can then draw out more specific gestures. “Where is that?” prompts singers to connect their gesture to a specific – imagined – location. More about pointing gestures here.

Fixing singers’ attention on the particular word they are singing right now, is also a Mindfulness exercise, which – like the steady beat of Tactus – encourages a state of Flow. More about Flow here. It’s how Monteverdi composed, word by word, and it sits well within the Stanislavsky tradition of Russian theatrical education.

The famous challenge from director to actor

I don’t believe you!

cannot be answered by exaggerated histrionics, by a gesture that is more historical, or by wider vibrato! It demands profound interior work from the actor. Caccini characterised the new, 17th-century style of singing as ‘like speaking in harmony’. Too much singerly attention on The Voice must be challenged immediately with “I don’t believe you”.

More about Emotions in Early Opera here.

Daily Schedule of Performances at Theatre Sats in Moscow, in the same week that this paper was delivered at GSMD in London.

At Theatre Sats, permanent members of the resident company perform all the different shows in a vast repertoire, and each of these shows comes around again every month or so. Singers and musicians have an immense daily work-load, often with two or more performances on the same day, plus rehearsals to revive old shows and yet more rehearsals to prepare new productions.

A typical day might begin with rehearsals for Rimsky-Korsakov, continue with a performance of Puccini and end with 17th-century baroque. To ensure continuity and provide a reserve for any eventuality, every show is double- or triple-cast: similarly for the orchestra.

Our first rehearsal for the violin band in Anima & Corpo was a delicate moment, introducing highly-experienced modern players to an utterly different aesthetic – straight tone, open strings and first position, slow bow-strokes. By lunchtime, we’d got through most of the material, and the musicians began to feel convinced by the unfamiliar sounds they were being asked to make. The afternoon rehearsal would go smoothly, we thought… until we saw a completely different group of string-players sit down for the second session!

A subtle feeling for a different kind of music-making is not something that can be marked into the parts – it has to be acquired through patient coaching and shared ensemble experience. It takes time. But once instilled in the whole company, it can be “absorbed” by new recruits more quickly, thanks to the ‘sitting-in’ tradition mentioned earlier.

Learning new material goes very slowly at the beginning, and then the final days of stage and technical rehearsal pass all too quickly: there is almost no time available in the middle for ‘artistic’ work.

It’s therefore crucial to engage with preliminary rehearsals, assisting repetiteurs as they drill notes into the singers’ heads. What is taught in these sessions tends to become up hard-wired, so mistakes must be ruthlessly eliminated. But this is also an opportunity to build-in fundamental elements of style, so a wise director will not be too proud to do a lot of the donkey-work themselves.

More about learning Monteverdi’s operatic roles here.

With limited time, and performers who spend most of their time working in quite a different style, our rehearsals focus on training general principles which can be re-applied in many different situations. Teaching principles, rather than imposing the director’s personal interpretation, leaves each individual with space to add their own artistic touches, and fits well with the historical concept of Art as a organised set of rules.

Of course, 17th-century aesthetics were also acutely concerned with the beauty and mysterious power of music: this is historical Science. We teach this in workshops, but for daily rehearsals we have to encapsulate complex ideas in punchy catch-phrase1s.

Sometimes it’s helpful to contrast 19th- or 20th-century practice with earlier styles, showing respect for musicians’ normal approach and for the coaching they receive from the Theatre’s mainstream conductors, whilst empowering them to do something very different with us, in the historical context.

The long legato lines of Romantic opera are contrasted with our mnemonic,

Breathe as often as you can!

Long notes long, short notes short!

brings rhythmic clarity, and encourages varied articulations. Subtleties of Tactus rhythm here.

Good & bad

does the same job for text syllables. More on Good & Bad here.

Ornamentation is not always relevant, and it’s certainly not a priority. Some visiting early musicians add ornaments, or ask about them; some resident musicians are keen to try for themselves. They all receive encouragement and advice. We will be more proactive as we come to French and later operas, for which ornamentation is an essential ingredient, like spices in cooking.

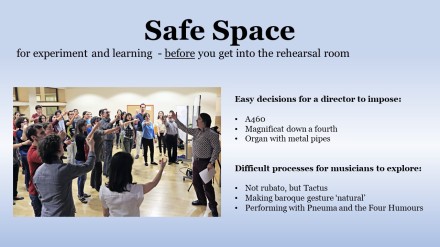

There is more time available at weekend workshops, where we explore links between period philosophy and the nitty-gritty of what one actually does in performance. Workshops also offer a ‘safe space’, a chance to try something utterly new. It’s a ‘safe space’ in the sense that we don’t have to demand instant success, and suitably-cushioned failure is accepted as an inevitable part of the learning process.

This training space is essential, not only for beginners acquiring fundamental skills, but– perhaps even more so – for professionals learning a new approach. These workshops are also the experimental laboratory that complements our academic research by providing a test-bed for new ideas.

Supposedly, Early Music is always trying out new performance practice ideas, but in the real world, there is a strong tendency to stay within everyone’s comfort-zone. It is much easier for a director to implement even quite radical decisions, than to change individual musicians’ deeply-ingrained habits.

New research findings demand new skills; new skills require new training methodologies; new methods have to be optimised and applied. All of this has to happen before new research can be applied in rehearsal, and polished for performance.

Our workshop formats vary. Our teaching style is to expound fundamental historical principles, and then guide participants towards making their own choices, within the style-boundaries. We usually have a wide range of abilities. Our motto is

Everyone has something to contribute, everyone has something to learn

– and that includes the tutors!

More about baroque gesture and historical acting here.

Many European conservatoires host a Historical Performance department, and most of those departments have partnerships with professional HIP ensembles. But we are working the other way around. We are hosted by a Theatre, so involvement with professional productions is a powerful, built-in “pull-factor” that sets our educational priorities. The complementary “push-factor” is new academic research, which drives our training agenda.

This is quite a different, and more integrated relationship between research, training and performance than one finds in most conservatoires.

Our Early Music focus on chamber-music skills, rhythmic accuracy and empowering individual performers is also beneficial to the Theatre’s mainstream work.

In today’s Russia, public funding comes from the State of Russia, or the City of Moscow. The City is richer than the State. Our host Theatre is State funded, and we do not expect additional public funding for this new venture against the current background of annual cuts in arts budgets, international sanctions etc.

Commercial sponsorship is focussed entirely on the highest slice of elite mainstream activity: there is no tradition of small or medium businesses supporting regional or local culture. But we have found some private support from enthusiastic individuals, and there are State and City funds available for specific activities, such as travelling productions.

The funding gap is covered by informal cross-subsidies that in Europe would be managed by assigning itemised costs to specific budgets, with cross-payments between departments. Performance fees, whilst smaller than European expectations, encourage directors to spend time on blue-skies research, and encourage musicians to invest in their own continued professional training.

Theatre Sats supports the Academy by providing resources off-budget. In return, OPERA OMNIA’s activities support the Theatre’s artistic, educational and outreach aims. We are blessed with senior management who take the long and wide view of this. We are also blessed with good team spirit, powerful ‘start-up’ energy, and a strong sense of involvement from all participants.

When money does change hands, it is rigorously controlled. But we devote less time to formal meetings and paperwork than in Europe. We can get things done quickly when there is a need or an opportunity.

We don’t pretend to be a full-time educational institution, rather we try to complement the work of conservatoires with our specialist focus on cutting-edge research, new training methods, new skill-sets and professional performance. We take a pragmatic approach, trying to fill gaps in knowledge and experience for each individual, leading towards specific performances.

Our concept of training as a ‘safe space’ and an experimental lab encourages us to respond continuously to new research findings. If there is a tendency for some conservatoires to educate for the past, for the world in which teachers themselves grew up, we are training for the demands of performances now and in the future, creating skill-sets beyond the limits of today’s Early Music habits.

Making baroque music in modern-day Moscow is often challenging. But the vibrant cultural scene, the energy and talent of Russian performers, enthusiasm from young audiences, and the Theatre’s support, create unique opportunities.

Last year, Theatre Sats was honoured with the European Opera prize for Education and Outreach. We at OPERA OMNIA are excited about our plans for the next few years. And we are proud to be developing performers and audiences for the Early Music of the future.

Pingback: Baroque Opera then and now: 1600 & 1607, 1970-2020 | Andrew Lawrence-King

Thank you, Andrew, so much for this utterly fascinating mailing regarding the various activities of Opera Omnia. Here in England I still struggle to try achieve at least a start on something similar, if necessarily on a more restricted basis. I’ve entered a partnership with Opera Settecento, a small company that has to date only produced concert performances. We are working towards the idea of running workshops on gesture and movement that would also involve potential audiences. At present I’m particularly exercised by the question of trying at least to some extent to re-create the symbiosis that existed between performer and audience in 18th c drammi per musica, an ambition that would require singers being able to improvise ornamentation in da capos With kind regardsBrian

Dear Brian, Thank you for your kind words. I’m interested to hear about your work with Opera Settecento, and I’d be delighted to contribute in any way, if you want.

Meanwhile, I think the two subjects you mention, Gesture and improvised Ornamentation, are both skills that need to be developed in the ‘safe space’ of experimental workshops, outside the pressures of the rehearsal room, before they are brought to public performance.

I have immense respect for Dean Barnett’s pioneering work on Gesture, but in one respect, my viewpoint differs. His approach was to coach performers in the precise gestures, creating a fixed “choreography” of the hands. This helps to maintain the historicity of the Gestures, but IMHO it can also lead to an audience perceiving the gestures as “fake”, “false”, “unconvincing”, no matter how beautifully they are executed. Hence the criticism often directed at productions with Baroque Gesture, that they are beautiful but un-emotional, too ‘stylised’ to move the audience’s emotions. This cannot be right, since the fundamental purpose of Gesture (also Music and all other Rhetorical arts) is to ‘move the passions’. My remedy is to allow controlled doses of improvisation, so that the performer feels that they ‘own’ the gesture, and the audience feels a sense of spontaneity. The secret is for the performer to maintain an intense, Mindful, focus on the word they are delivering right now, so that any gesture is directly connected to that word. “Suit the Action to the Word”, as the man wrote. One of the easiest way to administer controlled doses of improvisation is to allow the performer spontaneous choice between say two or three well-rehearsed alternatives. This is a stepping stone towards further degrees of freedom, once a greater number of historical options have been inwardly digested.

Probably this kind of “stepping stone” could be applied to da capo ornamentation too, proceeding from worked examples via spontaneous selection to genuine creativity on the spot.

All best wishes, Andrew