As a student in London in the early 1980s, I was told by some tutors (who should have known better) that there was no place for emotion in early music. But nowadays, in a development that owes more to changes in current social norms than to improved historical awareness, emotion has become a buzz-word amongst academics and performers aiike. Nevertheless, even amongst Early Music practitioners, the search for emotional intensity is often neither historical, nor informed.

Many directors and teachers do not work directly with performers’ emotional engagement. But handling emotions is a performance skill that must be taught, learnt, rehearsed and practised, like any other element of a well-rounded delivery. And, like every other aspect of musical and dramatic presentation, the performance practice of emotions changed over time, and between one location and another.

Most conservatoires, even those with a Historical Performance department, teach emotions (if at all) within a late romantic framework, focussing on the intensity of the performer’s emotional engagement, and modelled on the concept of the performer “expressing” their emotions through the medium of the composed score. But we have plenty of easily accessible and self-consistent period evidence as the basis for a more historically-informed approach.

In some debates amongst singers, an argument is sometimes advanced that seems dangerously close to saying: “just use more vibrato”! I am all in favour of historically informed use of vibrato, but let’s all agree that there is more to the rich inner world of human emotions than a wobble in the voice! Singing louder is also not the answer: in Cavalieri’s preface to the very first baroque music-drama, Anima & Corpo, he warns against forcing the voice, which would be detrimental to emotional communication. Rather, he (and many other sources) ask for frequent changes between forte and piano, and between contrasting emotions. Act with the heart, act with the hand: Motion and E-motion in Cavalieri’s preface

In the urge to convey baroque passions, many performers reach for the Romantic tool of rubato. Nearly all of us were taught this in our initial training, but in earlier periods, Rhetorical emotions were framed within the structure of measured rhythm, guided by the slow, steady beat of Tactus. Yes, this tactus could be tweaked according to changing emotions, but if you are not using Tactus in the first place, then you have no idea what you are tweaking! Frescobaldi Rules, OK? Caccini’s much-cited sprezzatura is even more misunderstood and mis-applied. The truth about Caccini’s sprezzatura. It’s certainly not the secret of emotional vocals (read below what Cacinni says that secret actually is).

In this post, I offer a brief introduction to the vast topic of Historically Informed Performance of Emotions. The post is dedicated to participants in Opera Omnia’s remake of Monteverdi’s lost masterpiece, Arianna (1608) from which only the famously emotional Lamento survives. But I hope the information will be useful to anyone working in early opera, indeed in any genre of baroque music.

There is ample historical evidence that emotions were highly significant in 17th-century music. The principal aim of Rhetoric is

muovere gli affetti – to move the Passions

From this well-known phrase, we should note two all-important points. Firstly, the historical discourse is not about “emotion” (singular), but about “Passions” (plural) and about “moving” from one Passion to another. All too often, modern-day coaches will ask for “more emotion!”. The performer might well ask in reply: “Which one?”. Emotion is not an all-purpose sauce that can be poured over any performance! In the historical context, we need to study various emotions, and practice moving between them.

Also, the concept of ‘moving the Passions’ begs the question: whose emotions are we trying to change? As soon as we ask the question, the answer is obvious: the audience’s. Here is the vital difference between Rhetorical (say, pre-1800) and Romantic concepts of emotional performance. In baroque opera, the purpose is to move emotions from the text and music into the hearts and minds of the audience; we do not really care about the performer’s own feelings. This is a world apart from the romantic cliché of the ‘genius performer, expressing emotions beyond those of the ordinary folk in the audience’!

Which Emotion?

Modern studies of emotions, facial expressions etc, attempt various classifications, based on 6 or more principal emotions. In the Rhetorical age, emotions were understood within the concept of the Four Humours. Although this model does not entirely match modern medical science, psychologically it works very well and can be used very effectively in modern-day performance of early music, just as singers use suggestive imagery (alongside hard science) to guide vocal technique. Of course, the vast array of human emotions cannot be mapped onto just four types. But the Four Humours provide general directions for moving the Passions, just as the four cardinal points (North, South, East, West) provide general directions for travel.

The Four Humours are at work in poetry, music and visual arts; in personality traits, moods and emotional impulses; in performance; and in psychological and physiological responses. The four well-known types are Sanguine (love, courage, hope: a warm, moist, outward passion associated with generosity, enjoyment of music, good food and red wine); Choleric (anger, desire: a hot, dry, outward passion associated with violence and strong drink); Melancholy (thinking too much, unlucky in love, sleepless: a cold, dry inward passion associated with what we would today call ‘the blues’); Phlegmatic (passive acceptance: a cold, moist inward passion, the feeling one has when influenza seems to have filled the entire head and body with green phlegm).

Character roles and individual lines of text often combine subtle mixtures of Humours. Dramatic speeches and operatic scenes often move from one Humour to another. But in this style, there are often frequent changes from one Humour to its contrary, word by word: this was considered to be the most powerful way to ‘move’ the audience’s passions.

How to move the Passions

I use simple exercises to help performers experience and convey each of the Four Humours, spending time on exploring each Humour individually by words, postures and movements. Then we practise moving from one Humour to another: slowly at first, and then faster, so that we can snap from one Passion to its contrary.

Working with a specific text (dramatic speech, poem, opera libretto, song-text etc), we identify which Humour (or which blend of Humours) is at play, word by word. It’s very important to bring this analysis right down to the word-by-word level at which baroque emotions operate. The first exercise is to determine how to perform each word: what colour of voice, what facial expression, what physical posture etc? All of this goes far beyond ‘changes in dynamics’, the simple contrast of forte, piano etc. Rather, each individual word gives a wealth of nuanced information, making it unnecessary for the composer to indicate such ‘dynamic markings’, which would in any case be facile and shallow.

To optimise the delivery of each word, we have to match the precise meaning of each specific word. At first, students tend to suggest approximations: “let’s sing this word loud, warmly, with more vibrato, brightly etc.” But there is a better way, what I call

the -LY principle

If the word is dolce ‘sweet’, sing it sweet-ly! If the word is amore ‘love’, sing it loving-ly! If the word is crudel ‘cruel’, sing it cruel-ly! And so on. The idea is simple, but powerful, and utterly historical. Try it! Experimental-ly!

Baroque Gesture is not merely a hand-ballet, though it should look elegant. Gesture is Rhetorical, i.e. based on the structure and passion of the words. And it’s always painfully apparent, when an actor puts their hand precisely where the director instructed, in the perfect historical position: it comes over to the audience academical-ly! Rather, each well-chosen and historically appropriate gesture has to be connected to, motivated (literally, set in motion) by the text, passionate-ly!

All this intense focus – on the specific word being sung at the particular time – results in increased Mindfulness, being ‘in the moment’. You don’t need to plan ahead or review backwards what you have just performed: stay intently in the present moment, and trust the librettist and composer to have done their job with (that previous element of Rhetoric), long-term structural planning.

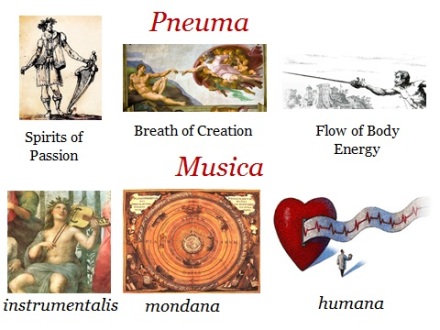

The renaissance concept of the Music of the Spheres linked cosmic energy to the harmony of the human body and to practical music-making. In parallel, period Science considered that emotions were communicated from performer to audience by Pneuma (the mystic spirit of creation, also the mystical energy of the body – like oriental chi – the mystical spirit of dramatic communication), transmitted as Enargeaia (the emotional power of detailed verbal description, poetic imagery, word-painting in baroque music), and carried by Energia (emotional energy) emitted from the actor’s eyes. You can practise believing this, whilst you perform: it will change what you are doing, in subtle, hard-to-describe, but powerful ways.

How to sing the Passions

The secret is not rubato, nor ornamentation (discouraged in the reciting style, according to Cavalieri, Peri, Monteverdi, Il Corago and many other early 17th-century sources), and certainly not vibrato. So what is it? How can we use the voice in this repertoire, passionately, appropriately, effectively?

Caccini’s preface to Le Nuove Musiche (1601) (here’s the link again) encapsulates the priorities, the method, and the technique, if you want to move your audience’s passions, in this repertoire. The priorities are Text and Rhythm: focus on the text, stay in the steady rhythm of Tactus. The method is a vocal production that is ‘between singing and speaking’ – see also Peri’s preface to Euridice (1600): you are not there to sing, your task is to help the audience understand every single word.

Don’t sing at me, speak to me!

By the way, the quickest way to destroy the illusion that you are ‘speaking’ in song, is to sustain the weak final syllable of the line. Amarilli, mia bel-LAAAAAA. So a very useful general rule is

Last note short!

Caccini’s recommended technique when there is a sustained note on a Good syllable, is to use crescendo/diminuendo on that single note. Caccini repeats this advice many times within his Preface, and he gives detailed examples of how to apply messa di voce (starting a long note softly, with crescendo) and exclamatione (starting a word like Ahi! or Deh! loud, then going immediately soft, and then crescendo). The standard way to present a long note is what I call

The Long Note Kit

Start softly and wait – then add crescendo – at the peak of the crescendo, relax and allow vibrato. Time this carefully with the Tactus, and with the typical process of Preparation-Dissonance-Resolution in a suspension. See How to study Monteverdi’s operatic roles for more detail.

And that’s it. The crucial concepts are not academically complex, just remember SSS:

- Speak each word according to its meaning

- Stay in tactus

- Shape long notes.

The challenge is that these simple ideas demand constant Mindfulness and intense concentration on Caccini’s priorities of Text and Rhythm. So of course, it’s much easier just to add vibrato and mess up the rhythm with rubato, and to create a false pretence of generalised emotion, without any particular link to what you are talking about. But the audience will see through that pretence, just as easily as we spot the insincerity of a fake politician! So let your Passions be strong, your Tactus stable: don’t rely on weak rubato and wobbly vibrato!

For further reading, I highly recommend Joseph Roach The Player’s Passion, which analyses theories of acting in light of the history of science, examining acting styles from the seventeenth to the twentieth century and measuring them against prevailing conceptions of the human body. The author explores how dominant theories of emotion, from the Galenic humor to the Pavlovian reflex, have shaped the critic’s changing standards of the natural order of life and the actor’s physical embodiment of it. The Player’s Passion has become a classic among theater historians and students of acting, and received the prestigious Barnard Hewitt Award for outstanding research in theater history.

For an analysis of the use of 17th-century Rhetoric to ‘move the passions’ in terms of modern medical science, try The Theatre of Dreams, which takes the Prologue for La Musica, in Monteverdi’s Orfeo, as a case-study.

Pingback: Three ways to make Early Music more expressive (And is there a ‘true way’?) | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Movement & Baroque Music: Mind, Body & Spirit | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Understand, enjoy and be moved! Listening to the Rhetoric of Orfeo | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: It’s Recitative, but not as we know it | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Fake News? Early Opera, aka Seicento Dramatic Monody | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: The Philosophy of La Musica | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Technique & Terminology (The Cremona papers: John McKean) | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Technique (The Cremona papers: John McKean) | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: OPERA OMNIA – Music of the Past for Audiences of the Future | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: The Practice of Tactus – Owners Workshop Manual | Andrew Lawrence-King

Every one of your posts is so valuable and thought provoking, but this seems to me especially valuable. Thank you so much!

Thank you for your kind words!