On the occasion of the 50th performance in repertoire of Cavalieri’s Anima & Corpo in George Isaakyan’s production Игра о душе и теле at Moscow State Theatre ‘Natalya Sats’ [Golden Mask award-winner in 2013], this article offers a translation of the Preface to the 1600 print, in which the publisher, Alessandro Guidotti, presents Cavalieri’s advice on ‘how to create a baroque opera’. Published in association with OPERA OMNIA Academy for Early Opera & Dance, read more here.

Emilio de Cavalieri’s ‘Rappresentatione di Anima e di Corpo’ (1600) is indeed the ‘first opera’. Jacopo Peri, whose ‘Euridice’ was performed later the same year, acknowledges Cavalieri’s role as originator of the style. (Earlier music-dramas by these two composers, notably Peri’s ‘Dafne’, have not survived.) So how did Cavalieri and his contemporaries seek to develop a new theatrical genre of fully-sung plays?

Guidotti’s original print with the full text of the Preface is available free online, here. More about Cavalieri’s music-drama here. Any (modern-day) debate about whether this work is ‘the first opera’ or ‘the first oratorio’ is irrelevant, since neither genre existed in 1600. The original designation is Rappresentatione – a representation, a show. Cavalieri’s music-drama on a moral subject is the earliest surviving example of the genere rappresentativo: it is through-sung in three Acts with a spoken Prologue, two Sinfonias to separate the Acts and a final Ballo. We are very fortunate that this beautifully printed score was published, a sumptuous collector’s item for seicento music-lovers, as a souvenir of the original production.

The Preface has very little discussion of airy philosophy. This is a practical guide, drawing on Cavalieri’s long experience as a Corago (artistic director) for spectacular theatrical entertainments involving music. And clearly, in composing Anima & Corpo Cavalieri followed his own advice, so that his music-drama is a perfect example of how to put into practice the principles he recommends.

This practical approach is found again circa 1630 in the anonymous MS Il Corago, and the two sources are remarkably consistent in their advice. Framing the period of court ‘opera’ as they do [Venetian commercial opera began in 1737], these two practical guides give us a clear understanding of the working priorities for the first ‘operas’ by Peri, Caccini, Gagliano and Monteverdi as well as offering insight into Roman music-dramas.

I’ve chosen a simple style of translation that stays close to Guidotti’s vocabulary and word-order, so that it’s easy to check the English version against the original Italian. Difficult or old words, or words whose meaning has changed since 1600 have been been translated using John Florio’s 1611 Italian-English dictionary. So that readers can distinguish my comments from Cavalieri’s text, my commentary appears below in red.

One way to discover Cavalieri’s priorities is simply to count how often he mentions key words. Crucial concepts emerge clearly:

- Contrast: diversi mutare varieta variare cambiar and their derivatives, 9 hits

- Passions: affetti and derivatives 6 hits;

- Specific Passions: pieta giubilo painto riso mesto allegro feroce mite etc, 10 hits

- Moving [the passions]: commova, muovere and derivatives 5 hits

This supports the argument that seicento music favours contrast, emotion, and contrasts of emotion. The importance of specific emotions and of changes one from emotion to another differs subtly from the Romantic aim for intensity of emotion. Sometimes, modern-day coaches ask singers for ‘more emotion’, as if emotion itself were a quality, as if one could pour all-purpose emotion into a performance, like pouring sauce. But in this repertoire, a request for ‘more emotion’ begs the question: ‘which one?’. A more appropriate coaching method for seicento opera is to look for, and intensify changes between specific emotions.

Other words also recur frequently:

- Recitando: with its derivatives, 6 hits

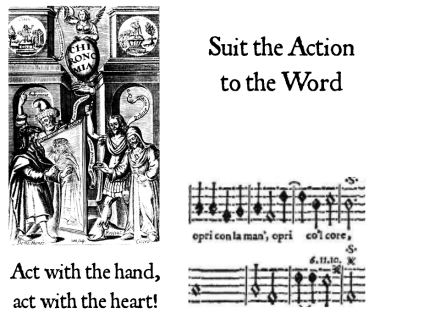

- Gesture: gesti, motivi, 5 hits

- Rappresentatione: with its derivatives 4 hits, plus 6 more mentions of specific genres of theatrical show

- Ballo: together with the verb ballare and their derivatives, 18 hits, plus 7 more mentions of specific genres/dance types, plus many mentions of specific steps

Recitare must be understood in its period meaning: certainly not ‘to sing Recitative’, and usually not as specific as ‘to Recite’ [whether singing or speaking]. The principle meaning is ‘to Act’. It’s important to keep this distinction in mind, and to avoid the modern assumption that there is a musical genre of ‘Recitative’, which has different rules from ‘normal’ seicento music. Cavalieri is discussing how to act in a stage show, specifically in a stage show that is through-sung (what we nowadays call ‘opera’).

Three decades later, Il Corago defines acting as ‘imitating with gesture’, whether silent, spoken or sung. Gesture is a vital part of early seicento acting, but as Cavalieri reminds us (below), it comprises not only gestures of the hand but motivi of the whole body. Period ‘body language’ is described in exhaustive detail in Bonifaccio’s L’Arte de Cenni (Vicenza, 1600), my English translation will be published later this year. My introduction to historical acting for the first operas, Shakespeare etc starts here.

We should keep in the back of our minds the academic nicety that Cavalieri’s music-drama was not called ‘opera’, with all the anachronistic expectations that word arouses, but rappresentatione: a show. And it’s quite a surprise to see how significant dancing is in Italian music-drama, conventionally regarded as text-based and opposed to later French ideals of dance-dramas. But in the context of Cavalieri’s experience as overall artistic director, his triumph with the dance-finale to the 1589 Florentine Intermedi, his practical insistence on variety and lively entertainment for the audience, and comparisons with the later Il Corago MS, as well as the popularity of social dancing in this period, dancing emerges as vital theme, often undervalued, in the development of the ‘first operas’.

All these key words – contrast, passion, acting, gesture, theatrical shows, dancing – are encapsulated in the period phrase muovere gli affetti, ‘moving the passions’. Cavalieri’s practical guide is all about motion and E-motion.

TO READERS

If you want to present on stage this work or others similar to it, and follow the advice of Signor Emilio del Cavaliere, so that this type of music, which he has revived, moves [the listeners] to different passions, such as to pity and to joy; to crying and to laughter and to others similar, as has been seen to be effective in the modern scene of La Disperatione di Fileno [The Despair of Fileno], composed by him, in which the acting of Signora Vittoria Archilei, whose excellence in music is very well known to all moved [the listeners] to tears marvellously, whilst the role of Fileno moved [them] to laughter:

Cavaliere is described as having ‘revived’, not ‘invented’ this type of music – dramatic monody, the representation in music of speech on stage. This reflects the period interest in re-discovering the power of emotional communication they had read about in classical Greek and Latin drama. The idea of ‘moving the passions… to tears and laughter’ is therefore a key topic.

As I say, if you want to put the show on, necessarily every element should be excellent: the singer should have a beautiful, well-pitched voice, they should keep the voice steady, they should sing with passion, piano and forte, without divisions (ornamentation) and in particular that they should pronounce the words well so that they [the words] are understood, and they should accompany them with gestures and motions not only of the hands, but of steps as well – these are most effective aids in moving the passion.

This advice for singers is an excellent check list of essential skills. Keeping the voice ‘steady’ encourages solid, well-supported voice-production and reminds us that vibrato is welcomed as an ornament, or a special effect, rather than as constant. Some early-music singers may be surprised to read that ornamentation is very restricted in this genre: passagi are prohibited, and cadential ornaments (discussed below) appear only infrequently. But Cavalieri’s restrictions on ornamentation are consistent with other sources, including Il Corago.

The instruments should be well played, and more or fewer in number according to the venue, whether a theatre or hall, which to be proportionate for this acting in music should not have a capacity of more than a thousand people, who should be comfortably seated, for greater silence and for their own satisfaction: since if you put on a show in a very large hall, it is not possible to make the words heard for everyone, and then it would be necessary for the singer to force, from which cause the passion is reduced; and so much music, lacking audible text, becomes boring.

Monteverdi’s Orfeo was played in a ‘small venue’, and most modern commentators are sceptical about period claims that Arianna had an audience of 6,000. Nevertheless, Cavalieri’s ideal venue is rather larger than the 400/500-seater chamber-music halls we sometimes think of as typical for early opera. And there is plenty more about large-scale ensembles below. But two important concepts from are already getting their second mention: no forcing (singers should even sing piano, when appropriate); it’s essential that the audience understands the words. And (singers take note!) in this repertoire passion is reduced if you sing too loud – as every actor knows, over-playing lines, shouting, generally ‘chewing the carpet’ just turns the audience off.

The need for the audience to be silent reminds us of the last stanza of the Prologue to Orfeo, in which La Musica calls on all nature (and by techniques similar to modern-day NLP, the audience too) to be still and silent. Read more about how La Musica hypnotises the heroes…

And the instruments, so that they are not seen, should be played from behind the backcloth of the scene, and by people who go along with the singer, without diminutions [ornamentation] and full [sound]. And to throw some light on those that have been useful in similar places, a lirone, a harpsichord, a chitarrone or theorbo as it is called, together make a really good effect: like also a soft organ with a chitarrone.

Cavalieri seems to seek the illusion that characters on-stage are just speaking, by hiding the instruments. In this period, the continuo ‘supports’ singers, ‘guiding’ the whole ensemble [Agazzari 1608, further discussion here], rather than ‘accompanying’ or ‘following’ in the modern sense [more about Monteverdi, Caccini & Jazz here]. Continuo-players should not add diminutions, but should play with full sound (to ‘support’ as Agazzari requires]. Many period sources ask the continuo to play grave.

Monteverdi also specifies organo di legno and theorbo in several places in Orfeo.

And Signor Cavaliere would praise changing instruments according to the passion of the actor; and he judges that similar music-dramas would not be good if they exceeded two hours, and should be divided up into Acts, and the characters should be dressed beautifully and with variety.

Changes of continuo instruments in Orfeo are according to the changing affetti: it’s not as simple as putting a certain instrument with each character (a solution sometimes favoured today).

Passing from one passion to another contrary, like from sad to jolly, from fierce to mild etc is enormously moving.

Cavalieri requires changes of emotion, and specific emotions – not just dollops of undifferentiated emotionality. And the importance of all kinds of contrast is beginning to emerge as a central principle.

When a soloist has sung for a bit, it’s good to sing some choruses, and to vary often the mode [tonality]; and that now the soprano sings, now bass, now contralto, now tenor: and that the rhythms and music should not be similar, but varied with many proportions [metres], which are Tripla [fast triple metre] Sestupla [very fast triple metre] and Binario [duple metre], and adorned with echos, and as many features [‘inventions’] as possible, like in particular [dances in varied metres], which bring these shows to life as much as possible, just as has been, in fact, the judgement of all the spectators;. and these Balli or Morescas if they can be made to appear out of the ordinary standard practice, they will have more beauty and novelty: like for example, the Moresca for a battle, and the Ballo based on a game or pastime: just like in La Pastorale di Fileno [The Pastoral of Fileno] three Satyrs came to battle, and based on this they did the battle singing and dancing on the Moresca ground. And in the game of La Cieca [Blind Man’s Buff] four Nymphs sang and danced, whilst they played around a blindfolded Amarilli, obeying the rules of the game of La Cieca.

Cavalieri calls for plenty of variety, contrast and novelty. He mentions Tripla and Sestupla, but not the slow triple-metre proportion of Sesquialtera [though all three triple-metres appear in Monteverdi’s Orfeo]. Given the strong correlation between the Preface and the music that follows, we would expect to find Tripla and Sestupla but not Sesquialtera when we realise Cavalieri’s notation of the proportional changes. My theory of proportions is supported by Cavalieri, some other modern-day theories are not. Read more about Monteverdi’s Time, here.

That’s certainly not to say that one shouldn’t do at the end with good reason a formal Ballo: but be well advised that the Ballo needs to be sung by the same [performers] who dance it, and with good reason to have instruments in their hands, which they themselves also play, for like this it will be more perfect and out of the ordinary, like that one which was put on by Signor Emilio in the great Comedy acted at the time of the wedding of the Most Serene Duchess of Tuscany in 1588.

The reference here is to Cavalieri’s spectacular success with the Ballo del Gran Duca, the finale to the Florentine Intermedi of 1589 [modern calendar]. There is more about performers simultaneously singing, dancing and playing below. The fact that singers simultaneously dance has implications for choice of dance steps and for proportions – leaping steps are impracticable for singers. See also this discussion of Cavalieri’s ideas applied to the Ballo in Monteverdi’s Orfeo.

When the composition is divided into three Acts, which according to experience gained should be sufficient, one would be able to add four fully-staged Intermedi, distributed so that the first would be before the Prologue, and each of the others at the end of its Act, observing this rule, that within the scene one makes small-scale music and a harmonious sinfonia of instruments, to the sound of which should be coordinated the movements of the Intermedio, having regard that there is no need for [sung or spoken] acting, as there would not be for example in showing the Giants who wanted to make war on Jupiter, or something similar.

Cavalieri’s term is intermedij apparenti – these include ‘sets and costumes, as well as recognisable narrative fragments, usually adapted from mythology; these are associated with the most spectacular of court entertainments… In contrast, intermedi non apparenti were far simpler, often consisting merely of a madrigal and performed without [changes of] costumes or sets.’ [Emily Wilbourne Seventeenth-Century Opera and the Sound of the Commedia dell’ Arte (University of Chicago, 2016, page 37)

The impression of seamless continuity given by the printed scores of Anima & Corpo and Orfeo is probably misleading: Cavalieri is recommending inserting Intermedi into this kind of three-act music-drama. But – an important point – since the drama itself is sung, the intermedi should avoid singing, whereas in a spoken drama such as La Pellegrina (Florence 1589), sung intermedi provide contrast as well as spectacle. Within Anima & Corpo itself, there are episodes (e.g. the entrance of Piacere and the Companions) that come close to being intermedi non apparenti. Indeed, the dramatic structure of the whole work, as a series of entrances, linked by the characters of Soul and Body whose story we follow [Intellect and Consiglio also make repeat appearances] is rather like a sequence of intermedi, a structure found also in mid-century French ballets.

And in each [Intermedio] one could make that change of scenery appropriate to the theme of the Intermedio: which, it should be advised, would not be able to include descending from clouds [stage machines], which could not synchronise the movement with the tempo of the Sinfonia, which would happen beautifully when there are Moresca or other dance-steps.

In the Preface to La Dafne (1608), Gagliano advises singers to walk in time to the music of their Ritornelli. But nevertheless, this comment of Cavalieri’s is puzzling: if not during such an intermedio, when can a descending cloud be appropriate, since there will always be the difficulty of synchronising its movement to the accompanying music?

The libretto should not exceed 700 lines, and to be suitable it should be easy, and full of short lines, not just of 7 syllables, but of 5 and 8, and sometimes in sdruccioli [accent on the ante-penultimate syllable] and with close rhymes, through the beauty of the music it makes a graceful effect:

Cavalieri is arguing for relatively simple poetry – the music will supply whatever gracefulness that might be lacking. High-style poetry would be in 11 and 7 syllable lines, and close rhymes would be avoided. Again, Cavalieri’s preference is for entertaining variety.

And in the dialogues statements and replies should not be very long; and the narratives of one solo [character] should be as brief as possible. And there is no doubt that the variety of characters enriches the scene with great beauty; as is seen well observed in the Pastorals of Satiro and of La Disperatione di Fileno, which, conforming with the intentions of Signor Emilio, the most noble Signora Laura Guidiccioni, of the Luchesini, noble lady of Lucca was happy to write; she also took the game of La Cieca from Signor Cavalier Guarini’s Pastor Fido, adapting that noble spirit very beautifully for her own purpose.

Once again, Cavalieri argues for contrast and variety.

ADVICE FOR THIS PARTICULAR SHOW, FOR ANYONE WANTING TO HAVE IT ACTED IN SONG

Placed at the end [of the published book] are the words without music, and with numbers corresponding to those that are in the music, in order to make it easy to check the music, and from those numbers can be recognised the different scenes and the characters who speak alone and together. At the beginning, before the curtain falls, it will be good to do some full music with doubled voices and a great quantity of instruments: one could very well use the madrigal number 86, with the text O Signor santo & vero: which is in 6 parts.

Cavalieri’s earlier recommendation suggests that there would also be an Intermedio at the very beginning, presumably before this ‘full music’ that begins the music-drama proper.

As the curtain falls, the two youths who have to act the Prologue will be onstage: and after delivering their material, Tempo [Time] will appear, and the instruments who have to accompany the singers, putting the first chord will wait for him to make a start.

The continuo repeat the first chord until Tempo is ready to start. Monteverdi’s Ulisse has a similar introduction to a scene, and Il Corago also recommends the continuo to repeat the harmony if extra time is needed for stage action. This (I argue) is what is meant by the idea of accompanists going with the singer – they ‘vamp till ready’ when stage action requires it, but they do not ‘follow’ in the sense of breaking time, even if the singer chooses (temporarily) not to be on the beat. Monteverdi frequently notates the vocal line anticipating or delaying, over a continuo-bass that maintains Tactus, in the Preface to Le Nuove Musiche (1601) Caccini describes what seems to be the same practice, see here. Both practices (free vocal line over timed bass, and ‘vamp till ready’ maintaining steady rhythm) are standard practice in today’s jazz, whereas mainstream ‘classical’ music expects accompanists to follow singers by breaking time, in the tradition of circa 1910 rubato.

The Chorus should be onstage, some seated, some standing, getting to hear what is presented, and amongst them sometimes changing places and making movements; and when they have to sing, they stand up in order to make their gestures, and then they return to their places:

As any stage director knows, characters on-stage, even Chorus-members, must be active listeners to the drama. Period art gives an idea of gestures of reacting and listening.

And the music for the Chorus being in four parts, one can, if wanted, double them, singing now four, and another time [all] together, assuming the stage is large enough for eight.

This is consistent with our modern understanding that the default expectation in this period was one singer per part. Monteverdi’s Orfeo was first performed with about 8 singers taking all solo roles and singing the choruses.

It will be good if Piacere [Pleasure] with the two Compagni [Companions] have instruments in their hands, playing whilst they sing, and playing their ritornelli. One could have a chitarrone, the other a Spanish guitar, and the other a little tambourine with jingles in the Spanish style which make little noise, exiting then whilst they play the last ritornello.

The scene of Pleasure & Companions is musically charming, with lively alternations of Binario, Tripla and Sestupla from the trio, contrasted with comments from the Body and Soul in what we today call ‘Recitative’. Cavalieri’s recipe for simultaneous playing and singing brings the instruments on-stage, visible to the audience (remember that the continuo-group is hidden behind the back-cloth), and gives the scene the flavour of an intermedio within the second Act.

When Corpo [Body] says the words Si che hormai Alma mia and what follows, he could remove such vain ornament, like a gold necklace or a hairpin, or something else.

This crucial moment marks the denouement of Act I, the Body’s decision, after much questioning and introspection, to follow the lead of the Soul rather than seek for earthly gratification. As composer, Cavalieri draws attention to these words with a sudden change of pace and harmony; as corago he suggests an action that goes beyond the usual hand-gestures, to make a symbolic rejection of earthly vanity. Underlying this small item of advice are two profound concepts of seicento music-drama, which differ sharply from the approach of modern-day Regieoper [in which the stage director seizes the freedom to create whatever he wishes]: music and stage-action work in parallel to tell the same story; both music and action are based on the text of the libretto. These concepts are stated explicitly in the Preface to Monteverdi’s Combattimento di Tancredi & Clorinda here page 19, and also in the anonymous Il Corago MS, modern edition here. Il Corago explains that a corago [artistic director] has universal authority in the theatre, but must serve the poet’s text. Choice of text is therefore an important consideration for both Cavalieri [who was himself a corago] and for the anonymous c1630 writer.

Mondo [World] and Vita Mondana [Wordly Life] in particular should be very richly costumed: and when they are divested, they should show that great poverty and ugliness underneath those costumes: this shows the body of death.

At the moments where each of these characters is divested, the score does not provide any extra time for the necessary stage action. These are examples of where the continuo would ‘vamp till ready’, either on a single harmony, or on a chord sequence, as recommended by Il Corago. Notice that the extra time is ‘quantised’ – the continuo will remain in Tactus.

The Sinfonias and Ritornelli can be done with a great quantity of instruments: and a violin, which plays the soprano part precisely, will make a very good effect.

This advice seems to look back to the kind of varied consorts heard in the 1589 Florentine Intermedi, and reminds us that polyphonic ensemble music might be performed with diverse consorts of chordal and melody instruments, as well as with the more homogenous ensembles of melodic instruments that we know from Monteverdi’s 1607 Orfeo.

The ending can be done in two ways, with a Ballo or without: if you don’t want to do a Ballo, it should finish in eight parts with the line which is number 91, doubling the voices and instruments as much as possible: the verse goes Rispondono nel ciel scettri e corone. If you want to finish with the Ballo, you should leave this verse unsaid, and starting to sing Chiostri altissimi e stellati the Ballo starts with a reverence and continenza [dance step]: and then follow other passi gravi [steps, as opposed to jumps], with heys [the dancers weave around each other] and solemn steps for all the couples: in the ritornelli it’s done by four who dance exquisitely a jumping dance with capers and without singing: and like this it follows in all the stanzas with the dance always varying, one time galliard, another time canario, and another corrente, which in the ritornelli will come across very well. And if the stage is not large enough for four to dance, at least two should dance: and get this ballo choreographed by the best maestro that can be found.

The stanzas of the ballo should be sung tutti, on- and off-stage: and all possible instruments should be put into the ritornelli.

All this detailed advice throws light also on the ballo in Monteverdi’s Orfeo – Lasciate i monti – see here for further discussion.

PARTICULAR ADVICE FOR THOSE WHO WILL SING WHILST ACTING, AND FOR THOSE WHO WILL PLAY

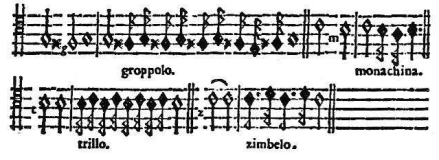

In the vocal parts will be found sometimes written in front of some notes one of the four letters g m t z which mean that which is shown in the example below.

Like this, for whomever is singing, as for whomever plays, it will be warned never to alter flats to sharps or sharps to flats except where the particular signs are placed: and similarly this should be understood for the notes that are raised with the sharp sign #, that only those specifically marked with # should be raised, even if the note is repeated.

The use of barlines was quite different in this period, our modern convention that accidentals apply within the same bar does not apply. This should be kept in mind, if working with a modern edition that imposes barlines.

The small figures placed above the notes of the instrumental Basso Continuo signify the consonances and dissonances according to the figuring: like 3 third, 4 fourth, and so on. When the sharp # is placed before or below a figure, that consonance will be raised: and in this way the flat b makes its own effect. When the sharp is placed above the notes [of the Basso Continuo] without any figure, it always means a major tenth.

Some dissonances and parallel fifths are made deliberately.

Some dissonances that are resolved ‘incorrectly’ are disguised in notation (but not in sound). Such transgressions of the rules of counterpoint are frequent in the ‘first operas’ – this is the ‘artistic licence’ that Peri requests, in his Preface to Euridice (also 1600) see here. Contrary to modern assumptions, there is no implication of rhythmic freedom.

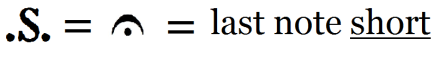

The sign .S. means coronata [the ‘crowned’ symbol, looking like a modern fermata sign], which is used to take breath and give a bit of time to make some gesture.

As in polyphonic music of this period, time for breathing (and gesture) is taken out of the last note of the phrase, maintaining the Tactus and starting the next phrase on time. The ‘fermata’ sign derives from the renaissance signum congruentiae, showing a consonance at the end of a phrase. In this period, the sign carries no implication of prolonging the note or breaking time: on the contrary, the assumption is that the note marked by this sign will be shortened, by default to approximately half-length.

FURTHER READING

Peri Preface to Euridice (1600) here

Caccini Preface to Le Nuove Musiche (1601) here

Agazzari Del sonare sopra’l basso (1607) here

Monteverdi Orfeo (1607) here.

Gagliano Preface to La Dafne (1608)

Anonymous Il Corago (c1630) here

How to Act in Early Opera & Shakespeare here

The title of this article cites the libretto, the end of the first speech of Time: ‘opri con la man’, opri co’l core’. The meaning of the Italian is ‘act with the hand, act with the heart’, but in the sense of ‘do good works’ – operare is cognate with ‘operate’. But since period acting links passions to gestures of the hand, it is not inappropriate to read into this line a reference (whether or not intended by the librettist) to historical stage-craft.

E VIVETE LIETI!

Pingback: Looking for a Good Time? | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: The Best Practical Musick: Thomas Mace’s Rule of Time-Keeping | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Rhetorical contrasts in Crisis: charm, communicate, console? | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Recitative for Idiots (but don’t use that word): three types of Dramatic Monody | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Baroque Opera then and now: 1600 & 1607, 1970-2020 | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Musing allowed – Reflecting on Music, Time & Play | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Understand, enjoy and be moved! Listening to the Rhetoric of Orfeo | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: The Minister’s Conditions in Monteverdi’s Orfeo | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Rhetoric, Rhythm & Passions: Monteverdi’s Orfeo in 2019 | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Baroque Opera & Rhetoric: audience reaction to Landi’s ‘Il Sant’ Alessio’ | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: It’s Recitative, but not as we know it | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: iL Corago – The Baroque Opera Director | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Fake News? Early Opera, aka Seicento Dramatic Monody | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Measuring a shepherdess’ heart-rate: Lamento della ninfa | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: The Philosophy of La Musica | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Emotions in Early Opera | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: How to study Monteverdi’s operatic roles | Andrew Lawrence-King

Dear Andrew

Thank you so much for this – I always find your posts extraordinarily stimulating. Because I’ve just seen a (poorly) semi-staged Orfeo, I went back to your remarkable film of the experimental staging you produced. It is tragic that it seems no one is building on your work in this field. Although getting a bit long in the tooth I still have ambitions – though probably more for later drammi per musica – and I wonder if you do anything more of this kind you could let me know – I’d just so love to come and learn from you.

With kindest regards Brian [Robins]