The Theatre of Dreams is Joe Griffin’s metaphor for the REM-state, that part of the sleep pattern characterised by Rapid Eye Movement and associated with dreaming. See Such stuff as dreams are made on, here.

Griffin’s Theory of Dreams suggests that an evolutionary breakthrough gave humans access to the REM-state whilst waking, in day-dreams and in hypnotic trance. Griffin and his co-writer, Ivan Tyrrel characterise this development, ‘the Mind’s Big Bang’, as the origin of consciousness, language and creativity. Their work also explains the often-noted connection between high creativity and mental illness.

My OPERA research project studies Operatic Performance as an Early-modern REM-state Activator. I hypothesise that around the year 1600, the first operas and Shakespeare’s plays ‘moved the passions’ of their audience by means of what we would now call Hypnosis. More about Music & Consciousness research strands here.

Of course, every fine performer somehow ‘casts a spell’ over their audience, but my research explores exactly how that spell functions. The aim of early opera was muovere gli affetti, to move the audience’s passions. Although present-day researchers are properly sceptical about period reports of audiences ‘laughing and weeping’, we know that music and drama does sometimes produce such emotional responses, even today.

I argue that the emotional response to music-drama might be heightened by hypnosis. And I hope to show that performance practices circa-1600 were particularly closely aligned with trance-induction processes, in order to create the psychological conditions in which the audience’s passions could indeed be moved.

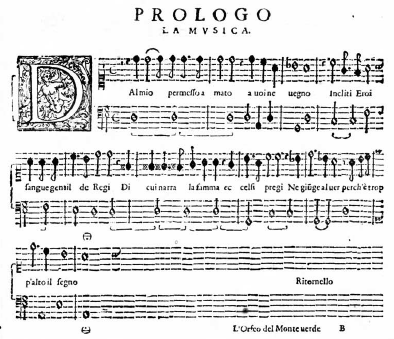

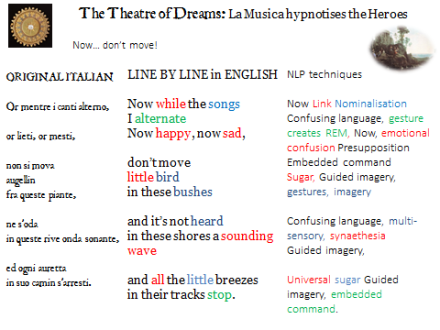

In this post, I analyse one of early opera’s most famous Arias, La Musica (the Prologue to Monteverdi’s Orfeo, 1607), in terms of Neuro-Linguistic Programming and as an Induction into Hypnotic Trance.

There is still considerable debate amongst researchers as to what Hypnotism actually is, and there is no single accepted scientific definition. The traditional view (shared by many academics) considers someone to have been hypnotised only if they have received a formal induction including the word “Hypnosis” after which they pass specific tests, for example arm levitation.

The modern view (shared by most practitioners, and largely derived from the practice of Milton Erickson in the late 20th century) considers that trance is a naturally-occurring state that we all enter and leave many times every day. Different people can reach different levels of trance in a variety of circumstances. In this view, self-hypnotism is easily achievable, and can be highly beneficial. Erickson’s methods were developed into the science of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), which studies how subtle use of language can alter the listener’s mental processes.

In spite of the lack of a formal definition, there is general agreement that Hypnotism involves heightened attention, absorption (being so concentrated on the focus of attention as to be unaware of other stimuli), and an imaginative experience so vivid that the boundary between internally generated perceptions and external reality becomes blurred. Hypnotism is often (but not always) linked to deep relaxation and an experience of inner calm and well-being.

As reported in the Oxford Handbook of Hypnosis, neuro-scientific observation has confirmed activation of specific areas of the brain in Hypnosis, consistent with an increase in focussed attention, a decrease in automatic vigilance (i.e. less watching out in case a sabre-tooth tiger should suddenly attack), and dissociation of the brain’s control and/or monitoring systems. It is this dissociation that leads to the subjective experience of things happening ‘by themselves’. Low-level unconscious processes instruct your arm to lift, and if those processes are dissociated from the normal conscious monitoring and/or control systems, you may have no conscious awareness of how or why your arm moved.

The intensification of inwardly generated experience together with reduced awareness of external stimuli outside a narrow focus of attention can lead to increased intensity of emotional reactions in Hypnosis.

Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin…

There are many ways to induce Hypnosis, but most Inductions mimic one or more of the characteristics of trance, in order to facilitate some kind of dissociation and direct the mind inward. Ericksonian hypnotists would say that ‘Once upon a time…’ can be considered an Induction, since these words tend to relax the listener, dissociate attention from the present moment and invite an imaginative response to whatever story follows. Temporal and spatial dissociation – ‘A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away’ – also encourages the mind to turn inwards and imagine whatever details are missing from the information stream of external reality.

Academic researchers are encouraged to use a Standard Induction, a prescribed script read in a monotone, often recorded so that the same Induction can be administered to a large group of experimental subjects. If the Induction is ineffective, the subject is presumed to be non-hypnotisable.

In contrast, most practitioners use different Inductions for different clients, observing that individuals vary greatly in what they respond to best. Someone whose primary sensory system is visual may respond very well to an Induction involving Guided Imagery, whereas someone more kinaesthetic might respond better to Progressive Relaxation. A logical thinker might readily dissociate when confronted with Confusing Language, a deep thinker might turn inwards to search for missing meaning in what he is told.

Many practitioners do not accept the validity of hypnotisability tests based on Standard Inductions. Richard Bandler, co-founder of NLP, is particularly scathing about such tests, which – he opines – only measure the ineffectiveness of the standard induction, and say nothing useful about the hypnotic abilities of the subject. Bandler believes that anyone can be hypnotised, if they permit it, and if the hypnotist has the necessary skills.

The core strategy of Ericksonian Hypnotism is ‘accept and utilise’. If at first the Induction does not work, then rather than labelling the failure as ‘Client Resistance’, the Hypnotist should accept the response as genuine, and utilise any information gathered to guide the choice of a new approach. For example, if the subject responds to an invitation to relax by getting more tense, the Hypnotist would be well advised to abandon an ineffective Progressive Relaxation Induction, and try something different, perhaps attention-locking and ‘sleight of mouth’ (see below).

Many Hypnotic Inductions have been published (there is an online selection here) and recorded on audio media. There is a large Hypnotism industry selling Inductions over the internet as mp3 files for download (I think Hypnotism Downloads are good, here). Once you understand the principles, you can easily write or improvise Inductions, for yourself or your friends. There is a list of books and links for further information, here.

In my research generally, and for this post in particular, I’m considering Hypnosis in practice, from the viewpoints of the Hypnotist and of the Subject, the person going into Trance. In academic language, this is a phenomenological and experiential approach: what happens, what is experienced? I take Trance to be an everyday, natural state. I consider that hypnosis is entered into willingly, as a collaborative process permitted, often actively encouraged by the Subject, within a safe environment created by a sense of mutual rapport. In NLP, it’s assumed that Hypnotist and Subject will both enter trance, each of them in a (subtly different) altered state of consciousness that optimises unconscious communication, deep learning, heightened emotions and hypnotic suggestibility.

In the special case of a performer entrancing an audience (or at least, those audience-members who are willing to ‘suspend their disbelief’ and become absorbed in the on-going drama), the performer’s altered state of consciousness is a particular type of Flow (also known as the ‘Zone’, an optimal state for elite, highly-skilled performance whether in the arts, sports or any other challenging situation). More about Flow here. More about connections between Flow and Hypnosis here.

Hypnotic Inductions are related to the typical phenomena experienced in Trance. Often, an Induction creates that characteristic blend of relaxation and concentration, or evokes specific physiological responses are evoked, so as to mimic the Trance state. Then the two-way nature of the mind-body link does the rest. [In a similar way, if you put a big smile on your face, you naturally feel happier and more relaxed. In fact, it’s sufficient to use electrodes to stimulate the smile-muscles, producing an utterly artificial smile on your face – you’ll still feel happier and more relaxed.]

So the traditional cliché of hypnosis, “follow the movement of this swinging pocket-watch” creates attention, focus, rapid eye movement and also a relaxing steady rhythm, all of which mimic the sensations of trance.

The rhythm of music circa-1600 is directed by Tactus, a slow beat at around one pulse per second. This steady pulse mimics the slow heart-beat of someone who is thoroughly relaxed. More about Tactus, here.

Now, as the Subject begins to slip into trance, it’s the moment for a Suggestion that encourages Dissociation , perhaps an invitation to imagine some far-away place. If that place is pleasantly dreamy, so much the better. ‘Imagine yourself lying on the beach, with the warm water lapping gently on the sand …’

Of course, TV adverts for tourist destinations use hypnotic techniques. And perhaps now you can appreciate why so many early operas are set in Arcadia.

According to NLP-guru, Richard Bandler, the most important elements of a successful Induction are:

- Rate of speech

- Timbre of voice

- Intonation (the ‘melody’ of speech)

- Breathing

Good Hypnotic speech employs a slower-than-normal rate of speaking, a soft tone of voice with downward inflections at the end of phrases. That downward inflection can transform the grammatical construction of a question – “You’d like to go into trance now, wouldn’t you?” – into a plausible statement. If the speaker emphasises certain words with an altered tone of voice, the phrase even becomes a command: “You’d like to go into trance now, wouldn’t you.”

Around the year 1600, the first opera-singers sang softly, in the intimate spaces where such court ‘operas’ as Monteverdi’s Orfeo were staged.

“One sings in one way in churches and public chapels and in another way in private chambers. In [church-music] one sings in a full voice … and in chamber-music one sings with a lower and gentler voice, without any shouting.”

Zarlino (Le institutioni harmoniche, Venice, 1558)

The pace of operatic Recitative varies with the drama of the moment, but (as we read in an anonymous c1630 guide for an opera theatre’s Artistic Director, Il Corago) in general it is somewhat slower than everyday speech. At the end of each short phrase, the last accented syllable is often considerably lengthened, and the most frequently used cadence has the melody descend to the final note. Il Corago and Jacopo Peri (in the preface to Euridice, 1600) agree that the modulazione of the voice, the melodic contour of recitative, is modelled on the ‘course of speech’ of a ‘fine speaking actor’.

Singers have to control the out-breath as they sing, and breathe in quickly between phrases. For audience members, exhaling more slowly than you inhale creates relaxation. For this reason, Hypnotists speak in short phrases, with frequent pauses in between, in a rhythm aligned with the Subject’s slow breathing.

These short phrases are chained together into long, flowing streams with few full stops. “Each time you breathe out … you feel more relaxed … and the more you relax… the more you feel… that you’d like to go into trance now… wouldn’t you.” We see the same structure in 17th-century sentence construction; many phrases are linked together; those phrases are separated by semi-colons; there are few full stops.

In operatic recitative, the composer similarly breaks up long sentences into short phrases: In questo lieto e fortunato giorno … ch’a posto fine a gl’amorosi affanni … del nostro semideo … cantiam, Pastori … in si soavi accenti … che sian degni d’Orfeo …. nostri concenti. [On this happy and lucky day …. which has put a stop to the relationship problems … of our godlike hero … lets sing, shepherds …. in such soft tones … that we honour Orfeo … with our music.] Notice again the ‘soft tones’. And by the end of this article, you’ll be able to recognise many more hypnotic techniques in this speech.

There are many Hypnotic techniques for obtaining compliance by means of subtle encouragement, as well as direct commands.

- Universal Quantifiers

General statements that “People find that music takes them naturally into trance”, or “Every dramatic performance alters the spectator’s state of consciousness” normalise the expected response and reassure the Subject.

- Implied Compliment

A more subtle approach informs that “intelligent and highly-creative people find it particularly easy to enter trance”. The implied compliment lowers resistance and encourages the Subject to align themselves with the complimented group.

A lot of advertising works on these hypnotic principles of implied compliments and universal statements. Buy this product and belong to the group of beautiful people shown in the advert. “Things go better with Coke”.

- Double Bind

This seems to offer a choice, but any choice produces the desired result:

“You can go into trance immediately, or you can take a few moments to relax gently before you go into a deep trance”.

- Embedded Commands

Subtle emphasis can create Embedded Commands, within such Generalities and Binds. “You can go into trance immediately, or you can take a few moments to relax gently before you go into a deep trance”.

- Analogue Marking

This emphasis, marked by changes in tone of voice, in the speaker’s gestures or position, can communicate directly to the unconscious mind by suggesting alternative meanings. “Now, your unconscious ( = now you’re unconscious) can deepen the transformation ( = deepen the trance)”

- Confusing Language & Trans-Derivational Search (TDS)

Unfamiliar words or confusing constructions lead the Subject to turn the mind inwards, in a search for hidden or ambiguous meanings. The technical term for this is Trans-Derivational Search. Confusing language, or confused emotions, might be delivered with unusually fast rate of speaking, or a silence might be left after a strange word: either way, the conscious mind is baffled, so that the unconscious takes over the search for meaning.

Suggestions for relaxation are often effective, but it’s even more effective to direct the mind inwards with subtle questions. “Close your eyes, and focus your attention on your hands. Notice if the right hand is more relaxed than the left. Or is the left more relaxed?” And every time the Subject breathes out slowly, or when the Hypnotist observes some small reduction in tension, this can be reinforced with an encouraging “Good. That’s right”. Feldenkrais Method uses these hypnotic techniques to optimise the mind/body link for effective learning of posture and movement.

As the conscious mind begins to let go, you can mix all this up with Confusing Language: “If the relaxed hand is right, you only have the other hand left, right? So right now, with your eyes left closed right up, see if you can write with the left, so the right is left to relax, and the left is right because it’s already relaxed, right? What’s left now is to go right into trance, right now, that’s right, you’ve left it all right behind you.”

- Silence

A good Hypnotist is not afraid of silence. Once there is relaxation and concentration, a long silence can be powerfully hypnotic.

- Attention Fixing & Eye Rapid Movement

Many Inductions relying on Attention Fixing, and/or creation of Rapid Eye-Movement. Experts use such methods for Speed Induction, with impressive results. See Richard Nongard’s demonstrations of Speed Induction, here.

Sleight of Mouth

A conjurer’s sleight of hand focuses your attention in a certain way, whilst he carries out the trick right in front of your eyes. In NLP, ‘sleight of mouth’ similarly dissociates the mind’s conscious attention on the actual words, away from the unconscious attention on the underlying meaning. Whilst the conscious mind deals with the surface details, the Hypnotist’s underlying message goes direct to the Subject’s unconscious. We’ve already seen examples of sleight of mouth: Universals, Binds, Embedded Commands, Analogue Marking, Confusing Language. Here is a quick check-list of some more techniques:

- Cause & Effect

It helps if the statement of cause is plausible, but the link to effect does not have be genuine. “Because you are reading this …” [that much is obviously true] “you will find it easy to learn self-hypnosis” [since the conscious mind accepted the first part, the unconscious is primed to accept the second part too].

“Because music is so charming to the ear, it can entrance your unconscious mind.”

- Links

Cause & Effect can be suggested more subtly, by replacing ‘because’ with another, less obvious link:

“Music usually charms your ears, and in that way it uses spiritual power to entrance your mind”

“Whilst I am singing, nothing moves”

- Sugar

A pleasant-sounding word works like the spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine go down.

“Happily, most people find it easy to relax into a gentle Trance.”

- Pacing

This links an obvious statement about the Subject’s current experience to a Suggestion.

“Every time you breathe out, you become more relaxed”.

- Presupposition

Rather than giving a command, the choice of words assumes the desired response:

“Whilst I am singing, nothing else will be heard.”

- Guided imagery

The Subject is encouraged to imagine that they are in some especially peaceful place. The idyllic surroundings support relaxation; relaxation and imaginative dissociation bring about hypnosis. A good Hypnotist will be artfully vague with his guidance, to leave maximum space for the Subject’s imaginative response, and to avoid jarring the subject out of trance with an over-specific suggestion that conflicts with the Subject’s inner experience.

I prefer radio to TV, because the pictures are better.

Similarly, the bare stage of a Shakespearian theatre leaves space for the audience’s imaginative response.

“Think when we talk of horses, that you see them

Printing their proud hoofs i’ the receiving earth;

For ’tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings…”

Shakespeare Henry V Prologue

- Multi-Sensory Absorption

Guided imagining that involves all the senses offers a rich and absorbing experience for the Subject. Absorption encourages hypnosis. Appealing to several senses also allows for individual differences between Subjects: some people are more creative with images, others with sounds, others with taste, smell or physical sensations (touch, or the position of the body).

- Sensory Confusion

Confusing sensory information and synaesthesia (crossed-over senses: a warm colour, a blue note) create a surreal, dream-like experience and direct the mind inwards in the search for meaning.

- Emotional confusion

“I can calm every troubled heart, and now with noble anger, now with love, I can enflame even the most frozen mind”

- Nominalisation

Nominalisation is an NLP term for replacing active verbs – to love, to understand – with abstract, semantically complex nouns – Love, Understandings. Abstraction, ambiguity and complexity send the mind inwards in a search for meaning.

Compare the active language of ‘Many people know about you and praise you. But they still underestimate you, because you are so cool!’ with these nominalisations:

“Fame narrates heavenly Praises about you, but does not reach the Truth, because the Sign is too high.”

- Selectional restriction violation

This is the NLP-term for re-attributing the Hypnotist’s Suggestion to some abstract concept or inanimate object:

“Your chair wants you to go into trance”.

- Now

This one word is very powerful. ‘Now’ focusses attention and suggests an immediate response.

“Now, you can identify these Induction techniques at work in La Musica’s Prologue.”

In the first strophe, La Musica introduces mild spatial Dissociation with the mention of far-away Permesso (a river sacred to the Muses – a more thought-provoking name than the expected Parnassus, the sacred mountain-home of the Muses). The actor Relaxes the audience with generous compliments, and fixes their Attention with varied gestures. High gestures are particularly hypnotic: rolling the eyes upwards is itself a marker of trance, and fixing the gaze a little above the horizon is often used to begin an Induction.

The Ritornello gives about 12 seconds pause, in which the listeners might come out of their developing trance. This is another hypnotic technique, known as Fractionation, in which letting the Subject come partially out of trance helps them go deeper in again, afterwards. Strophe 2 introduces Emotional Confusion and a Post-Hypnotic Suggestion: in the next hour or so, your emotions will be moved by a ‘story in music’.

The next strophe Suggests much more profound influence, by means of a subtle Link and Selectional Restriction Violation: some special kind of musical instrument takes you into the deepest part of your unconscious. “The more…. the more” is another NLP technique: the more you listen to La Musica, the more you will go into trance.

In the penultimate strophe, the intensity of the Induction is temporarily reduced (Fractionation), but the language of ‘desire spurs me’ holds the Attention. La Musica starts to tell a story (story-telling is a favourite method for hypnotherapists to deliver Suggestions) with vivid imagery, super-natural events and locations. Mention of far-off, idyllic places – the mountains of Pindus and Helicon, both homes of the Muses – Relaxes again, and encourages spatial Dissociation.

The final strophe is the most powerfully hypnotic, taking the audience deep into trance just before the drama itself begins. Attention is fixed three times with ‘Now!’, several sleight of mouth techniques are interwoven, with a strong Embedded Command: “Don’t move!”, which creates the catalepsy characteristic of profound hypnotism. Pastoral imagery simultaneously suggests Relaxation.

The line “and it’s not heard” is particularly subtle. Italian ne (= and not) makes a confusing link. And once you are told “it’s not heard”, you strain your ears to listen for whatever it is (we are not told what it is, until after a hypnotic pause).

“Sounding wave” would have been more unusual, more synaesthetic, to a 17th-century audience than it is to us: we are accustomed to the scientific concept of Sound as a Wave, they were not. This strophe mixes sensory channels, imagery and emotion, and then suddenly …. stops!

And as La Musica holds all the audience in trance with a commanding gesture, Monteverdi notates an 8-seconds silence before the orchestra plays again. The Prologue is ended, La Musica leaves, and the favola in musica (story in music) begins.

This kind of hypnotism is not authoritarian, it cannot be forced; it needs the listener to collaborate. It relies on the audience suspending their disbelief, engaging their imagination, and voluntarily relinquishing some control to La Musica. And if you let her ‘influence your soul’, her story of Orpheus can make you laugh and cry. You don’t make yourself cry, the drama does it. But you could have stopped yourself, if you had chosen to, especially if you had decided at the beginning of the show to resist becoming involved.

La Musica’s Induction is an invitation to participate deeply in an imaginative experience.

When this hypothesis of seicento hypnosis first came to me, I was concerned at the apparent anachronism: after all, the word ‘hypnosis’ was invented by James Braid around 1841. But the knowledge and practice of hypnosis is much older, of course; there is evidence of it in shamanic traditions and other ancient cultures. And there is a 17th-century word for the persuasive use of unusual, image-laden, semantically dense, sometimes confusing language, in order to sway the listeners’ emotions, the study that today we call NLP: Rhetoric.

Rhetoric is the Neuro-Linguistic Programming of the Renaissance

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our website www.TheHarpConsort.com . Further details of original sources are on the website, click on “New Priorities in Historically Informed Performance”

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago, and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions.

Pingback: Three ways to make Early Music more expressive (And is there a ‘true way’?) | Andrew Lawrence-King

I often read your article for getting a clear idea. A Unique idea thanks for sharing. This post is really useful.

mindrelaxation

Thank you for your kind words. I think there are many connection points between concepts from Historical Performance Practice in music, and modern-day studies of Hypnotism, Mindfulness, Feldenkrais, Tai Chi and other disciplines that operate within the mind-body link. More cross-disciplinary work is needed here.

I have found that this article on hypnotic techniques appearing in early 17th-century opera has been warmly accepted by hypnotists, for whom the techniques are instantly recognisable, and the application plausibly effective. But performing musicians have been much more sceptical!

Pingback: A Tai Chi state of mind | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Understand, enjoy and be moved! Listening to the Rhetoric of Orfeo | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Rhetoric, Rhythm & Passions: Monteverdi’s Orfeo in 2019 | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: It’s Recitative, but not as we know it | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: The Philosophy of La Musica | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Emotions in Early Opera | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Act with the hand, act with the heart: motion and e-motion in Cavalieri’s Preface to ‘Anima & Corpo’ | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Keep calm & concentrate: may the Force be with you! | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Text, Rhythm, Action! Research, Training & Performance | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Flow (The Oxford papers) Part 1: What’s in a name? | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Quality Time: how does it feel? | Andrew Lawrence-King

This has to be one of the most fascinating blogs I’ve read in some time. You do a superb job of weaving several apparently disparate threads together to make a persuasive tapestry. Or have I allowed myself to be entranced?