Remaking the fourth opera in the Monteverdi trilogy

The Indiana paper – watch the video here.

In September 2017, OPERA OMNIA presented in Moscow a re-make of Monteverdi’s lost masterpiece, Arianna (1608), setting Rinuccini’s libretto ‘in Claudio’s voice’ around the sole surviving musical fragment, the famous Lamento. Our aims were to offer performers and audiences an operatic context for this celebrated soliloquy; to reverse the standard processes of musicological investigation by applying new, rigorous creativity to previous analysis; and to re-assess Performance from the perspective of Historically Informed composition, initiated by period practices of improvisation.

With generous help from Tim Carter, we applied methodologies from Monteverdi’s Musical Theatre (2002) and took inspiration from Wilborne’s exploration of Seventeenth-century Opera and the Sound of the Commedia dell’Arte (2016). The practical challenges of re-composing and staging a lost work demanded a sharp focus on Monteverdi’s methods and word-by-word engagement with Rinuccini’s text. The Tragedia emerges as a powerfully effective theatre-piece, with sharp characterisations and dramatic twists in affetto. The visual impact of Bacchus’ arrival (Heller, Early Music October 2017) is matched by aural shock as lamenting strings are blown away by ‘hundreds of trumpets, timpani and the raucous cry of horns’.

Following the interdisciplinary learning methods of the period, Monteverdi’s circa 1608 works were closely imitated, identifying literary citations, and transforming composed models according to rhetorical principles and in steady Tactus. Channelling Peri, Monteverdi and the anonymous Il Corago, historically informed improvisations – basso continuo, declamatory speech and baroque gesture – guided re-composition towards the ‘natural way of imitation’, an ideal that Claudio felt he came closest to in his Arianna.

This article was written as a paper to be given at the Indiana University Historical Performance conference, May 2018. Music examples can be heard on the accompanying video here. In-line footnote numbers correspond to captions in that video.

Scores for the music examples are available for study here: by clicking you agree not to share these scores with anyone else, nor to perform them without first obtaining my written permission.

OPERA OMNIA (Director, Andrew Lawrence-King) is the new Academy for Early Opera & Dance, Institute at Moscow State Theatre Natalya Sats (Intendant, Georgy Isaakyan).

There are currently two early operas running in repertoire at Theatre Sats: Anima & Corpo (60th performance this season) and Celos, aun del aire matan (third season) as well as a mainstream production of Alcina and the anti-opera Guido d’Arezzo. In September 2017, the International Baroque Opera Studio presented the premiere of ARIANNA a la recherche, which is now being recorded for CD release. Future productions include L’Europe Galante and Andrew Lawrence-King’s Kalevala. The 2018 International Baroque Opera Studio will link training/ performances of Purcell’s King Arthur and the Round Table Academy research event.

OPERA OMNIA’s Anima & Corpo won Russia’s highest music-theatre award, the Golden Mask. Theatre Sats won the 2017 European Opera Award for Outreach and Education.

ARIANNA a la recherche:

re-making the fourth opera in the Monteverdi trilogy

MUSIC EXAMPLE 1: Stampa il ciel con l’auree piante Utopia Chamber Choir, Helsinki

- On 28th & 29th September last year, OPERA OMNIA, the Academy for Early Opera & Dance recently founded at Moscow State Theatre ‘Natalya Sats’, presented the premiere of ARIANNA a la recherche, Andrew Lawrence-King’s remake of Claudio Monteverdi’s 1608 masterpiece. This setting of Ottavio Rinuccini’s tragedia ‘in Claudio’s voice’ was performed by the advanced students and young professionals of the International Baroque Opera Studio.

WHY?

I am immensely grateful to Prof Tim Carter for the valuable insights and helpful advice he contributed to this project. But his first comment to me played devil’s advocate: why reconstruct Arianna?

2. The entire opera takes place on a deserted beach, the libretto often repeats itself, there’s lots of recitative, and whole scenes are devoted to rhetorical debate on the well-worn subject of Love versus Duty. Even the original production’s aristocratic promoter herself described the first draft of the libretto as ‘rather dry’.

Recalling the famous question, why climb Mount Everest, I’m tempted to answer for Arianna, “because it’s not there!”. All that survives of the original music is the famous Lamento.

3. Lamento d’ Arianna published for voice and continuo in 1623, also transcribed as a 5-voice madrigal and in religious contrafacta.

But Monteverdi regarded Arianna, composed in Mantua the year after Orfeo, as his greatest work for the stage.

4. Monteverdi revived Arianna as his first production for the public theatre in Venice (1640); it came closest to his ideal of the ‘natural way to represent’ drama in music, via naturale alla immitatione.

“Arianna was by all accounts a huge success, and its central lament for the protagonist reportedly moved the ladies in the audience to tears.”

Tim Carter Monteverdi’s Musical Theatre (2002)

Certainly, the construction of almost the entire opera was a formidable challenge. But any half-way decent setting will present an intriguing opportunity for performers, audiences, critics and musicologists.

5. Re-making a ‘lost opera’ as a research project.

“It is the task of the historian to create appropriate frames of reference within which Monteverdi’s works might plausibly have been viewed and understood by competent members of their first audiences.”

“The longest chapter in [Monteverdi’s Musical Theatre] concerns the ‘lost’ works, where Monteverdi’s music does not survive, for all that one can still say a good deal about it. In general, however, my approach tends to be less philosophical or aesthetic than pragmatic; I am not so much concerned with my own, or even Monteverdi’s grand statements as with the nuts and bolts of how a seventeenth-century musician might have written for, and worked within, the theatre.”

Carter

In academic study of the arts, the reverse side of the coin from analysis is creativity. Historically Informed Performance searches to understand and follow the composer’s intentions: the reverse of that process is to become the composer oneself. Composing and performing a setting of Rinuccini’s libretto was perhaps the ultimate practical investigation.

I was inspired also by Emily Wilborne’s work, looking beyond surviving documents to the rich variety of sounds that period audiences would have heard.

6. Emily Wilborne Seventeenth-century Opera and the Sound of the Commedia dell’Arte (2016), which examines Virginia Ramponi-Andreini’s performance in (and one might well say, creation of) the title role of Arianna. A professional actress brought into the 1608 production after the death of court singer Caterina Martinelli, La Florinda (to use her stage name) triumphed from first audition to final performance and may well have contributed her improvisatory skill to what became the published text and music of the famous Lamento.

Building on my 5-year Text, Rhythm, Action! program at the Australian Centre for the History of Emotions, this realisation of Arianna with historically informed staging investigates not only lost sound, but the visual and emotional experience of that 1608 theatrical event.

It’s possible that publicising this project might flush out of hiding an original source for Monteverdi’s setting. For performers and academics of the future, this would be a great outcome. Meanwhile, the investigatory effort would not be wasted: on the contrary, comparisons between the original and my reconstruction would reveal gaps in knowledge and understanding.

So ARIANNA a la recherche attempts to set the famous Lament in its operatic context, with all due humility that the exercise of imitating Monteverdi can never be more than an exploration, an Essay in music, a baroque Versuch.

7. “Constructing meaning is an exercise both challenging and fraught with danger. But it is an essential part of the theatrical experience.”

Carter

MUSIC EXAMPLE 2: Deh, se quel arco stesso Utopia Chamber Choir, Helsinki

The character Amore (Cupid) remains on-stage throughout the drama, invisible to the other, mortal characters. But when Bacco and Arianna fall in love, Amore becomes visible to mortal eyes, as Nunzio Secondo (the Second Herald) tells us. Meanwhile in this chorus, after Arianna’s Lament and the noise of Bacco’s arrival, the Fishermen are still hoping that Teseo might return. As they remain fixed in their previous opionions, so my music returns to the very first song they sang. This music is from Su l’orride paludi, one of two Act-end choruses that seems to require through-composition, even though the libretto prints strophes. Strophes 1 and 2 recount the Orpheus story; strophes 3 and 4 (another story of love and Hell) are discussed later in this article; this is the fifth and last strophe.

AIMS

I was not trying to ‘reconstruct’ the lost manuscript: I wrote a score for music-drama, for a performance in the theatre, with singers, musicians and an audience. Keeping this practical outcome in mind encouraged me to see the libretto not only as singable text, but also as a theatrical script, with hints of scenery, costumes, entrances and exits, of the emotional background and changing moods of the various characters, and of their baroque gestures.

- The anonymous c1630 Il Corago defines acting as ‘imitating with gesture’.

Recitare … imitando le azioni umane, angeliche o divine con la voce e gesti… rappresentare le medisme azione cantando

To act… by imitating the human, angelic or divine actions with the voice and with gestures… to perform the same action singing.

Notice that the 17th-century Italian word recitare means simply ‘to act’: it does not carry the baggage of our modern assumptions about Recitative. Indeed, Il Corago’s definition lists three ways of acting – tre maniere di recitare: spoken drama, sung ‘opera’, and wordless mime.

Historical Action is more than just ‘baroque gesture’, it includes not only gestures of the hands, but facial expressions and movements of the whole body. as well as conventions for onstage positions.

Whilst there is tendency nowadays to think of gesture as a ‘bolt-on’ extra to historically informed musical performance, period sources make it clear that Action (not only gestures of the hands, but facial expressions and movements of the whole body) was fundamental, ‘built-in’ from the outset. As he began work on a new project, Monteverdi searched the libretto for powerful emotions to express, and for gestures (implied by the words) which could be imitated in music.

- In a series of letters to Alessandro Striggio (librettist for Orfeo) concerning an opera being planned in 1627, La finta pazza Licori (a few months later the project was abandoned), Monteverdi discusses and links the concepts of ‘imitation’ (dramatic representation, whether in acting, singing or instrumental music) and gesture.

“The words [should] mimic either gestures or noises or any other kind of imitative idea that might suggest itself” (24 May)

“I am constantly aiming to have lively imitations of the music, gestures and tempi take place behind the scene (10 July)”

This implies instrumental music, played di dentro, behind the scenic backdrop, as specified in Orfeo. The lead role in La finta pazza was to be sung by Margherita Basile. Instruments would imitate not only the singer’s music, but also her acting, specifically her gestures.

After Carter

His instructions for the Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda call for the actors’ passi & gesti, the instrumentalists’ varied sounds and the declamation of the text to be delivered in such a way that the three dramatic modalities come together in a united representation.

- Monteverdi Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda: ‘Three Actions’, i.e. three ways of presenting drama: gesti & passi (gestures and steps), music, text.

“che le tre ationi venghino ad’incontrarsi in una imitatione unita.”

In such works, Monteverdi’s aim was for to create effetti – not only good effect in general, but also the ‘special effects’ of non-musical noises (e.g. the sounds of battle), and the emotional effect of ‘moving the passions’ – affetti. In this remake of Arianna, my aim was similarly to unite the essential concepts underlying Monteverdi’s vision of what we now call ‘opera’.

- Effetti/Affetti, Energia/Enargeia

Lawrence-King ARIANNA a la recherche: drama as Action; acting as Gesture; music and acting as Imitation; musical Effects that move the audience’s Affects; all rooted in the communicative power (Energia) of detailed poetic imagery (Enargeia).

Of course, many modern ensembles have programmed other baroque music around the Lament. And there have been two recent attempts to set Rinuccini’s libretto. In 1995, Alexander Goehr composed a modernist score for an ensemble including extensive pitched percussion, saxophone, sampler etc, but preserving some of Monteverdi’s vocal lines. In spite of a talented cast of singers, critical reviews were unfavourable.

In 2015, Claudio Cavina, director of the ensemble La Venexiana, presented a semi-staged performance of his assemblage of Monteverdi’s music, reset to Rinuccini’s verses.

- Contrafactum is a thoroughly historical procedure – we have 17th-century settings of Monteverdi madrigals to devotional texts and even a contrafactum of Arianna’s Lamento with a religious text in Latin, the Pianto della Madonna. The proof of a good contrafactum is not only that the word-setting works in terms of accentuation, word-painting and changes of affetto, but also that any remembered associations connected to the original text complement the new function of the music. This requires careful consideration and adaptation of pre-extant music to the new text.

Whatever success this private performance enjoyed was sadly eclipsed by Cavina’s subsequent illness.

My re-make differs from both these previous projects in that the output is a HIP production of baroque opera that is new-composed, rather than a collage of contrafacta. Nevertheless my writing was carefully modelled on Monteverdi’s circa 1608 compositions.

METHODOLOGY

Monteverdi’s letters reveal his negotiations with librettists, and his bold changes to their poetical texts. I was unable to negotiate with Rinuccini, so most of the changes I experimented with in first drafts were removed in later versions. What remains is Monteverdi’s madrigalian technique of mashing-up text to create additional layers of meaning.

MUSIC EXAMPLE 3: Ma tu, superbo altero Utopia Chamber Choir, Helsinki

This is the last strophe of the Act-end chorus Avventurose genti. As discussed below, there is a pattern of parallel changes of affect from strophe to strophe, until this last strophe breaks the pattern with an outburst of anger from the normally placid Fishermen.

I began with a set-piece aria passeggiata at the beginning of Act V. By 1608, such a florid air is rather old-fashioned, but it remained the way for music-drama to indicate supernatural powers.

- Aria passeggiata indicates supernatural powers, at the appearance of a god -in Arianna, Amore and Baccho – or where magic, especially the power of music, is at work –Harmony’s Prologue and Arion’s aria in the 1589 Florentine Intermedi, and the aria Possente spirto, in Orfeo (1607).

After workshopping this first sketch at Opera Omnia, I made a few changes. Amore’s strali, the burning rays of his arrows of love, might fly in whatever direction, but seicento settings tend to use downward passaggi to depict them. The second draft was dedicated to Jordi Savall and Maria Bartels and performed at the celebration of their marriage.

Later, I deleted a text-refrain I’d introduced, and added a Sinfonia and Ballo for the Entrance of Bacco, eloquently described in Follino’s eye-witness report:

- Follino’s description of the Entrance of Bacchus, the final scene of Arianna (1608)

“Bacco with the beautiful Arianna, and Amore in front, were seen to enter onto the stage on the left side of the stage, surrounded in front and behind by many couples of Soldiers dressed with beautiful arms, with superb crests on their heads. Once they were on stage, the instruments that were within began a beautiful aria di ballo, one part of the Soldiers danced a very delightful ballo, weaving in and out amongst themselves in a thousand ways; and whilst these danced, another part of the Soldiers took up the accompaniment of the sound and ballo with the following words: Spiega omai, giocondo Nume / L’auree piume.”

The danced chorus has the same metric structure as the final chorus of Peri’s Euridice (1600), another Rinuccini libretto.

MUSIC EXAMPLE 4: Spiega omai, giocondo nume

As Carter notes, the giocondo nume is Apollo, even though the celebrations are for the arrival of Bacco.

I also looked for Rinuccini’s coded indications of aria or dance-metres.

- Indications of Aria (any repeating structure, especially rhythmic patterning) within Recitative (acting):

Diegetic songs, entrances of Gods and sententious statements, as well as hints from poetic metre for dance-rhythms or triple-metre. Expressions of movement (in Arianna, walking, running and sailing!) or particular emotions similarly give an excuse for more regular patterning, even for the extra impetus of triple metre.

Monteverdi’s practice in Orfeo was to reduce Striggio’s Act-end choruses to a single strophe. I considered this option, since Rinuccini’s Arianna is much longer than Orfeo. But I was persuaded that with so much recitative (implied by Rinuccini’s choice of poetic styles), the remake would need every possible moment of musical interest, whether aria or chorus.

I may have gone slightly too far, in creating brief moments of what we might today call Arioso in the midst of long recitative scenes. But Rinuccini gives occasional hints: Consigliero hears the note (notes, i.e. musical aria) of Teseo’s heart in a speech that one might otherwise have assumed to be recitative. Was this Monteverdi’s ‘natural way’ to handle dramatic scenes, which he preferred over the more artificial separation of Aria and Recitative in Ulisse and Poppea?

- Models for composition of ARIANNA a la recherche: Monteverdi’s compositions circa 1608, including madrigals, Orfeo, the Ballo delle Ingrate, the surviving Lamento and other pieces inspired by it, and the 1610 Vespers.

ALK’s musical activities during the period of composition: re-reading books of Monteverdi madrigals, directing a staged production of Ballo delle Ingrate, performing Orfeo, running a workshop on the Lamento and listening to live performances of Sfogava con le stelle and other madrigals.

I deliberately pre-loaded my subconscious mind with lots of good examples, re-reading books of Monteverdi madrigals, directing a staged production of Ballo delle Ingrate, performing Orfeo, running a workshop on the Lamento and listening to live performances of Sfogava con le stelle and other madrigals, over a three-month period of thinking and composing. This is comparable to Monteverdi’s pace of composing. I drew on my skills as a continuo-player to think from the bass upwards, ‘improvising onto paper’; and on my theatrical experience to create melody from gestured declamation.

Cut-and-Paste

In a number of works of this period, a particular word or short phrase is often set to precisely the same notes.

For example, Ohime! is often set falling through a ‘forbidden’ interval, c F#, syncopated against a strong bass D between the two syllables. Or the same pattern, a tone higher.

Almost certainly, this is the musical representation of a conventional way of declaiming such words in the spoken theatre, which (as Peri and Il Corago tell us) is the model for seicento recitative. Where such words or short phrases occur in Rinuccini’s Arianna, I copied Monteverdi’s standard recipes for them.

Transformation

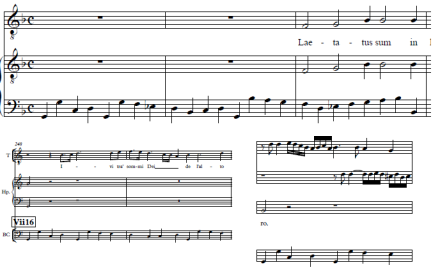

There is, to my mind, an important distinction between modelling (my intention) and contrafactum (a valid approach, but not my choice). So when I took the walking bass from Monteverdi’s Laetatus sum in the 1610 Vespers as a model for Bacco’s show-stopping aria, I transformed it from sacred G minor to an exuberant G major, which ends up recalling Orfeo’s triumphant return from hell, Qual honor.

Cued by Rinuccini’s words Faran del tuo bel crin ghirlanda d’oro (They will make a golden garland of your hair), my violin-writing cites Monteverdi’s madrigal Chiome d’oro (Golden hair), which he himself borrowed from to set the Psalm Beatus Vir.

My string ritornello for Apollo’s Prologue, a tenor singing tenderly to the lyre of love – su cetera d’amor teneri carmi – takes its rhythmic structure and rising phrases from the ritornello to the tenor solo from Monteverdi’s Book VII (1619) Tempro la cetra – I tune my lyre to sing the honour of Mars. But instead of the hard hexachord of G major harmonies and sharpened notes in Monteverdi’s melody, my music for Apollo’s cetra adopts the soft hexachord with G minor harmonies and melodies with flats.

It’s important that any associations such models evoke are appropriate. Here, if the listener is reminded of another lyre being tuned, that’s all to the good, especially if they also appreciate the significance of the shift from warlike major to pastoral, even melancholy minor.

MUSIC EXAMPLE 5 Apollo ritornello OPERA OMNIA International Baroque Opera Studio

Word-painting

Apollo’s first words Io che ne l’alto… (I, who on high…) naturally require a high note on alto, matching the actor’s upward extended right hand. Rinuccini provides the grateful composer with many such cues.

- Original Italian texts:

They will make a golden garland of your hair – Faran del tuo bel crin ghirlanda d’oro

Singing tenderly to the lyre of love – su cetera d’amor teneri carmi

I who on high… – Io che ne l’alto…

Pattern recognition

In the madrigal books, Monteverdi responds to texts reminiscent of verses he previously set, with music that recalls his earlier work.

- Pattern recognition:

For example, the Lettera Amorosa with its paean to a woman’s red hair (La Florinda had red hair) frequently recalls moments from Arianna’s Lamento. Rinuccini’s libretto for the opera often suggests well-known texts, from his own work – Ballo delle Ingrate (also 1608), Euridice (1600) and the madrigal Sfogava con le stelle (1603) as well as from Striggio’s Orfeo (1607) and the Florentine Intermedi (1589).

There are also very frequent cross-references within the libretto, with many parallels between Arianna’s Lament and the Nunzio’s description of her lamenting, between Teseo’s meeting with Consigliero and the Pescatori’s report of that meeting, and recurring images of sunrise and sunset.

Arianna may well contain references that escaped me, and we cannot know how many references Monteverdi would have noticed, or chosen to link with musical citations. But I deliberately took every opportunity I found to make use of pattern recognition. My score may therefore have more citations than Monteverdi’s practice, but Rinuccini’s libretto has more citations than other early operas.

Musical Example 6: Or sappi figlio OPERA OMNIA International Baroque Opera Studio

Declamation

I declaimed aloud every single line of the libretto, searching for the best rhythms and pitch contours, accompanying my spoken recitation with historical gestures. Even though Rinuccini praises the eloquence of Bacco’s gestured conversation with Arianna, I had not previously realised how significant the ‘language of gesture’ was for composers in this repertoire, as well as for performers. Once the gestures are decided, the music has to correspond.

I had to correct my initial errors, and wrestle with challenging gesture-puzzles: lightning must strike downwards of course, but an emergence out of the deep sea must move upwards, yet somehow allow a low hand-position for the final word profondo. Out from that deep sea come Nymphs and Divas, whose music in my setting recalls the Nymphs coming out to dance in the Ballo Lasciate i monti from Orfeo.

MUSIC EXAMPLE 7 Indi per l’alto ciel Victor Sordo & The Harp Consort

Re-composition

Although it is not specifically indicated in Rinuccini’s libretto, instrumental music is clearly required to delineate Act boundaries, to allow characters to enter or exit or as ritornelli between strophes of arias or choruses. Here, bolder compositorial action was necessary, since there was no text to inspire modelling techniques. But the affetto of the situation and the identity of the characters give clear guidance: battaglia figures for Teseo and his Soldiers, pastoral recorders for the nocturnal Fishermen, sad modes for Arianna.

- Recomposition:

My setting of Arianna’s aria of hope Dolcissima speranza is modelled on Monteverdi’s well-known song Si dolce e’l tormento, and I reworked that material again as exit music for the lamenting princess. In another sinfonia for the protagonist, I take the thematic material of Josquin’s 4-voice Mille Regretz (one of those earlier chansons which were remembered in the 17th century and performed in new, ornamented settings) and rework it as a polyphonic fantasia for string quintet in the style of Monteverdi’s prima prattica.

Realisation

None of the published versions of the Lamento matches descriptions of the 1608 production, in which La Florinda was accompanied by ‘violins & viols’, her outbursts interspersed with commenting choruses from the Fishermen. Thus, even the surviving music requires considerable intervention. This was perhaps the most delicate work of all.

- ‘Violins and viols’:

Modelling my work on Monteverdi’s string accompaniments to Clorinda’s speeches in Combattimento and on the last strophe of Possente Spirto in Orfeo, I gave Arianna the full complement of five strings. ‘Violins and viols’ probably means just small and large string instruments, but does suggest a full consort.

As a performer, I have always opposed the addition of editorial string accompaniments to basso continuo, so it was a strange experience to write such additional accompaniments myself! Modelling my work on Monteverdi’s string accompaniments to Clorinda’s speeches in Combattimento and on the last strophe of Possente Spirto in Orfeo, I gave Arianna the full complement of five strings (‘violins and viols’ probably means just small and large string instruments, but does suggest a full consort), leaving sections with fast-changing harmonies to be accompanied by continuo alone. The resulting contrasts bring out both Arianna’s grandeur and her vulnerability, the essential elements of baroque tragedy.

Music Example 6: Lamento: Lasciatemi morire Opera Omnia and Trio: In van lingua mortale Utopia Chamber Choir

The period principle of Tactus structured contrasts in the speed of declamation, by notating changes of note-values within a constant pulse.

Music Example 7: Trio: Ahi! Che’l cor mi si sprezza Utopia Chamber Choir

The distribution of speeches by the Fishermen poses a question: what should be sung by the chorus, what should be ‘spoken’ by an individual?

- Pescatori – Fisherfolk

The Pescatori have a similar function to the Pastori (Shepherds) in Orfeo, indeed Teseo’s first mention of them refers to a pastore. Tim Carter alerted me to subtle hints of contrasting character-types, and of awareness or lack of knowledge of previous action, amongst individual members of this chorus. So I sketched out various distributions: my working notes refer to “Mr Happy = Tenor 1”, “Cassandra, aka Ms Miserable = Soprano” “Mr Sleepy = Bass” etc! I scored Rinuccini’s chorus speeches for 1-6 voices – the larger ensembles might well be doubled, according to contemporary information on the size of choruses.

OUTCOMES

- Outcomes

My version can be performed with 10 singers (with a lot of doubling), but would be better with 14 (with some doubling, as suggested by period reports). This would correspond to the nine singers of the all-male Mantuan capella (SSS AA TT BB) plus a mixed-gender group of five guest soloists (including La Florinda as Arianna and Francesco Rasi doubling Apollo in the Prologue and Bacco in the Finale).

Applying the principle of constant Tactus at around one beat per second, my setting takes 2 hours and 33 minutes, which fits well with Follino’s report of two and a half hours in 1608.

It isn’t for me to comment on the value of my own composition, but I can report with enthusiasm that Rinuccini’s tragedia makes wonderful music-theatre, full of emotional contrasts and dramatic twists. Teseo and his victorious soldiers enter happily, lieti, felici; Arianna is fearful and sighing, but Teseo declares himself fedelissimo, utterly faithful ‘till death us do part’. The audience, remembering classical mythology and forewarned by Venus and Cupid, knows better.

The opera is full of such dramatic irony. The Fishermen sing blithely of the happy dawn just as Teseo’s ship is sailing away; and even when they understand that he has abandoned Arianna, and rage against him, they persist in hoping for his eventual return.

Repetitions and cross-references help the audience follow the plot, connecting prediction, event and report.

- Emotions

Contrasts: Teseo and his victorious soldiers enter happily, lieti, felici; Arianna is fearful and sighing.

Dramatic Irony: The Fishermen sing blithely of the happy dawn just as Teseo’s ship is sailing away; and even when they understand that he has abandoned Arianna, and rage against him, they persist in hoping for his eventual return.

Repetitions and cross-references: As Teseo departs, bitter suffering asprissimo martire will never leave him; even though Arianna, not yet realising her fate, tells the Fishermen how willingly she is deceived by dolcissima Speranza, sweetest but illusory hope; they remember his gestures and dolorous emotion, i gesti e i dolorosi affetti.

Contrasts: Speaking to Cupid, Venus primes the audience to be sympathetic to Arianna’s plight Or sappi… e di pieta t’accendi. With an abundance of great anger, dove grand’ ira abbonda, the first Herald curses Teseo’s boat and calls down vengeance from heaven. In contrast, the second Herald will cheerily praise Love amidst heavenly joy. But first Arianna must lament, despair, call for Teseo to be drowned, repent of her anger and resolve to die. And when the irrepressible Dorilla tries to jolly her along, Arianna proudly asserts her royal authority, in additional music preserved in manuscript sources of the Lament Nacque regina…al mio voler t’acqueta. Sweetest hope becomes malevolent Speranza iniqua serving only to feed bitter sorrow nudrir l’aspro dolore.

As Arianna’s emotions reach their lowest ebb, Rinuccini creates a coup de theatre, silencing the lamenting strings with noisy clamour ‘confused, rumbling voices and signal blasts, thousands of warlike trumpets, resounding timpani and raucous horns. The aural and dramatic contrast must have been shocking. Wendy Heller’s article in Early Music (written simultaneously with, but independent from, this project), evokes the visual spectacle of Bacchus’ triumphant arrival. The 1608 audience would have had the double shock, first hearing Bacchus’ arrival (the dozy Fishermen think it’s Teseo, of course), and then after the second Herald’s lengthy build-up, seeing his all-singing, all-dancing triumph.

MUSIC EXAMPLE 8: Bacco Fanfare OPERA OMNIA International Baroque Opera Studio

- The Triumph of Bacchus

Sound: “confused, rumbling voices and signal blasts, thousands of warlike trumpets, resounding timpani and raucous horns”

Vision: Lions, tigers, Silenus and his donkey, and a horde of tambourine-playing Maenads.

Strophic choruses

25. The seemingly wide-focus lens of a ‘History of Emotions’ approach could also be narrowed down for the detailed work of setting Rinuccini’s many strophic choruses. Taking as my model the varied strophes over a ground bass of Alcun non sia – Che poi che nembo rio – E dopo l’aspro gel in Act I of Orfeo, my default-mode was to set the first strophe, and then re-compose variations for subsequent strophes, changing vocal scoring and word-rhythms as appropriate.

In many choruses, it became apparent that Rinuccini had structured parallel shifts of affetto in one strophe after another, so that musical gestures optimised for the first strophe could serve for similar emotional changes in subsequent strophes. But the abrupt shift from pastoral (or piscatorial) escapism to anger at Ma tu, superbo altero demanded a similarly abrupt break in the smooth sequence of strophic variation. And the complex imagery of Si l’orride paludi, evoking the power of love even in Hell, required through-composition. The third and fourth strophes of this chorus refer to the myth of Alcestis, who sacrificed herself to save her husband and was rescued from Hell by Hercules, leading to Rinuccini’s enigmatic line Cambio d’amato sposo (exchange of beloved husband).

Cambio d’amato sposo

Here is an explanation for the suitability of Arianna, a tragedy, at the celebrations of a dynastic marriage. Katerina Antonenko’s research for this project revealed that there was indeed an exchange of bridegrooms for Margaret of Savoy.

- Real-life historical parallels to the Arianna story (Katerina Antonenko):

Margherita’s father, Carlo of Savoy (dedicatee of the Prologue in one print of the libretto) hoped to strike a peace-treaty with Geneva on advantageous terms, sealed by marrying his daughter to Prince Henri of Geneva. Negotiations broke down, and Carlos switched allegiance decisively to Italy, marrying his daughters into the Mantuan Gonzaga and Modena’s Este families.

Rinuccini mentions ‘the enemy King’ (Geneva’s ally, Henri IV of France), theatrical Giove represents Pope Paul V, whose blessing was withheld for the Genevan “Teseo” and later given for the Mantuan “Bacchus”, Francesco Gonzaga.

The backstory of the Minotaur reminds us of animal-mask helmets worn by the Savoy troops.

Now we can understand how Teseo’s Counsellor could be allowed to insult Arianna onstage, in the presence of the real-life bride, Princess Margherita. The attempt at character assassination misfires: for the Mantuan audience, it is Teseo’s reputation that is permanently stained. Behind the conventional debate over Love and Duty, the dynastic fortunes of Geneva and Mantua are in play. From the very first scene, divine figures inform us that Arianna’s ultimate destiny is already settled: the Mantuan audience needed this reassurance that Teseo’s, i.e. Geneva’s suit was doomed to failure, that the Bacchic Francesco’s triumph was always pre-ordained.

Our Arianna project continues to progress, with an international CD recording in progress. At Opera Omnia, in addition to ongoing baroque productions, we continue to create new Baroque operas.

- ARIANNA a la recherche CD recording in collaboration with professional ensembles and conservatoires in Moscow, St Petersburg, Helsinki, Barcelona, London etc.

Current OPERA OMNIA productions:

- Cavalieri Anima e Corpo

- Hidalgo Celos aun del aire, matan

- Monteverdi Orfeo

- Purcell King Arthur

- Landi La morte d’Orfeo

- Handel Orlando

New Baroque operas by Andrew Lawrence-King:

- Kalevala (linking Finnish traditional music to medieval organum and Vivaldi)

- Carolan’s Travels (imagined encounters between the Irish harp-composer Turlough O’Carolan, Jonathan Swift and George Frideric Handel before the first performance of Messiah in Dublin)

- Teatro a la moda (Vivaldian comedy)

- New Ground (a baroque parallel to Britten’s Young Persons Guide to the Orchestra)

- Pepys’ Hamlet (Morelli’s To be or not to be inspires the opera Purcell never wrote)

Amici, ecco… spettacolo giocondo!

Musical Example 8: Nunzio Secondo Victor Sordo with The Harp Consort

- The Second Herald in Arianna:

My friends, behold this joyful spectacle! Amici, ecco… spettacolo giocondo

Pingback: Prattica di Retorica in Musica – Inventio | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: The Young Person’s Guide to Early Opera – What are the Top Ten 17th-century operas? | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Understand, enjoy and be moved! Listening to the Rhetoric of Orfeo | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Rhetoric, Rhythm & Passions: Monteverdi’s Orfeo in 2019 | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Baroque Opera & Rhetoric: audience reaction to Landi’s ‘Il Sant’ Alessio’ | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: iL Corago – The Baroque Opera Director | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Fake News? Early Opera, aka Seicento Dramatic Monody | Andrew Lawrence-King