At the end of September 2017, OPERA OMNIA will present the premiere of Andrew Lawrence-King’s remake of Monteverdi’s lost masterpiece, Arianna (1608), performed by the young professionals and advanced students of the International Baroque Opera Project at Moscow State Theatre ‘Natalya Sats’. Read more about the project here. Singers, continuo, instrumentalists and technical theatre specialists may apply to take part, here.

The first article in this series explores “WHY remake Arianna” here. There are two parts to the question of ‘HOW’ to remake a lost baroque opera, focussing respectively on result and process: how should the result come out, what kind of work should it be? And how should that result be achieved, by what methodology? You can about the first part of this question, HOW – in what format – to remake Arianna? here.

In this present article I examine the second part of the HOW question: by what process. Having decided to make a new composition modelled on Monteverdi’s surviving c1608 works, I completed the score and uploaded it for participants last week. This post reveals my methodology: how I went about the job. In short, my motto throughout was

What might Claudio have done?

Prof Tim Carter’s inspiring book, Monteverdi’s Musical Theatre (2002), demonstrates solid academic techniques for investigating lost works, with considerable space given to his discussion of Arianna (1608), from which only the famous Lamento survives, published for solo voice and basso continuo, and in the composer’s arrangement for madrigal consort. It’s worth noting that neither of these versions matches descriptions of the 1608 production, in which the actress La Florinda performed the Lament accompanied by ‘violins & viols’, interspersed with commenting choruses from an ensemble of Fishermen. Thus, even the surviving music requires considerable compositorial intervention.

As analysed by Tim Carter, Monteverdi’s letters reveal his various ways of working: sometimes he would begin with set-piece arias (especially if he already knew who the singer would be), sometimes he worked through the libretto from the beginning, often he left dances to the end (waiting for more information about how the dances should be structured). Sometimes he negotiated with his librettist to make the text more suitable for music-drama, sometimes he made bold changes to the poet’s work.

More by chance than by plan, I ended up following all of these options. I began with a set-piece chorus and aria passeggiata at the beginning of Act V. By 1608, such a florid air is rather old-fashioned, but it remained the way for music-drama to demonstrate supernatural powers, at the entrance of a god -in this case, Amore (Cupid) – or where magic is at work – Arion’s aria in the 1589 Florentine Intermedi, or Orfeo’s display of the power of music, Possente spirto, in Orfeo (1607). We tried out this first sketch at an Opera Omnia workshop in Moscow, with an informal performance at Theatre ‘Natalya Sats’.

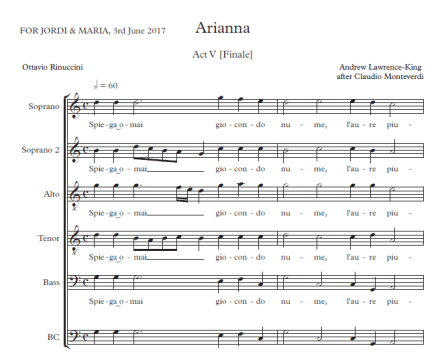

After that first try out, I reviewed this excerpt and made a few changes. Amore’s strali, the burning rays of his arrows of love, might fly in whatever direction, but seicento settings tend to use downward passaggi to depict them. I adjusted the ornamentation accordingly. The polished version was dedicated to Jordi Savall and Maria Bartels and performed at the celebration of their marriage in Cardona, on 3rd June 2017.

I then continued my composing with another set-piece aria, the Prologue for Apollo, modelled (as is the text, with all its references to the cetera d’amore) on La Musica’s prologue to Orfeo. Then I completed the choirs and dances for the remainder of the Act V finale. Later on I removed an introductory chorus I had added to this Act, replacing it with a Sinfonia and dances for the Entrance of Bacco, eloquently described in Follino’s eye-witness report:

Bacco, with the beautiful Arianna and Amore in front, were seen to enter onto the stage on the left side of the stage, surrounded in front and behind by many couples of Soldiers dressed with beautiful arms, with superb crests on their heads. Once they were on stage, the instruments that were within began a beautiful aria di ballo, one part of the Soldiersdanced a very delightful ballo, weaving in and out amongst themselves in a thousand ways; and whilst these danced, another part of the Soldiers took up the accompaniment of the sound and ballo with the following words: Spiega omai, giocondo Nume / L’auree piume;

This danced chorus has the same metric structure as the final chorus of Peri’s Euridice (1600), another Rinuccini libretto, similar also to Monteverdi’s setting of Striggio’s verses for Orfeo

Ecco pur ch’a voi ritorno

Monteverdi and Peri set the triple-metre poetry under a ‘time-signature’ of C, which produces a slow measured dance, ideal for the solemn movements of this ‘ancient Greek’ style Chorus. More about Monteverdi’s proportional notation in Tempus putationis – getting back to Monteverdi’s Time here.

With the beginning and end of the show safely committed to paper (or rather, saved in Sibelius music-writing software), I then worked through the whole libretto in order. I also went back over my tracks several times, catching errors and revising. In pre-planning, I looked for Rinuccini’s indications of aria or dance-metres. There are diegetic songs, entrances of Gods and sententious statements (all cues for aria) as well as hints from poetic metre for dance-rhythms or triple-metre aria. [The period meaning of the word aria begins with any repeating structure, especially rhythmic patterning]. Expressions of movement (in this opera, walking, running and sailing!) or strong emotions similarly give an excuse for more regular rhythm, even for the extra impetus of triple metre.

Monteverdi’s practice in Orfeo was to reduce Striggio’s Act-end strophic choruses to a single strophe (sometimes this makes the text hard to understand). I considered this, since Rinuccini’s Arianna is much longer than Orfeo. But I was persuaded by Prof Carter (who has given generously of his time and energy to support this project), that with so much recitative implied by Rinuccini’s choice of styles, my remake would need every possible moment of musical interest, whether aria or chorus. After all, the first try-out in 1608 had been deemed “rather dry”, before the arrival of commedia dell’arte actress La Florinda in the title role, and various changes made by Rinuccini and Monteverdi.

I may have gone slightly too far, in creating brief moments of what we might today call arioso in the midst of the long recitative scenes. But Monteverdi himself reported that in this work he came closer than ever to ‘the natural way’ to handle dramatic scenes: closer even than in Ulisse and Poppea, where he separated aria from recitative more self-consciously. And Rinuccini gives occasional hints: Consigliero hears the note (notes, i.e. musical aria) of Teseo’s heart in a speech that one might otherwise have assumed to be recitative.

There was also something of a jigsaw-puzzle in distributing the various speeches of the Pescatori (Fishermen): which should be choral, which individual? This chorus has a similar function to the Pastori (Shepherds) in Orfeo, indeed Teseo’s first mention of them refers to a pastore. Prof Carter alerted me to subtle hints of contrasting character-types and awareness or lack of knowledge of previous action amongst individual members of this chorus. So I sketched out various distributions: my working notes refer to “Mr Happy = Tenor 1” and “Ms Miserable = Soprano” etc! I scored their speeches for 1-6 voices – the larger ensembles might well be doubled, according to contemporary information on the size of choruses.

After completing the score, I calculated the required company of singers: my version can be performed with 10 singers (with a lot of doubling), but would be better with 14 (with some doubling, as suggested by period reports). This would correspond to the nine singers of the all-male Mantuan capella (SSS AA TT BB) plus a mixed-gender group of five guest soloists (including La Florinda as Arianna and Francesco Rasi doubling Apollo in the Prologue and Bacco in the Finale).

MODELLING TECHNIQUES

I took as my models Monteverdi’s compositions circa 1608, which include madrigals, the opera Orfeo, the Ballo delle Ingrate, the surviving Lamento and other pieces inspired by it, and even the 1610 Vespers. Specific references in Rinuccini’s text sent me again to Orfeo, Ballo delle Ingrate and the madrigal Sfogava con le stelle as well as to Peri’s Euridice (1600) and the 1589 Intermedi. Peri’s description of his recitative, imitating the pitch contours of a declaiming actor over a bass defined by the changing emotions of the text, is reinforced by the latest work of musicologist Emily Wilbourne, which connects Seventeenth-Century Opera and the Sound of the Commedia dell’Arte. I also took note of Tim Carter’s observation that whilst Peri’s recitative tends to circle around, Monteverdi’s tends to go either up or down, and (noted by Carter and Wilbourne alike) often first up and then decisively down, in the most passionate moments.

I deliberately pre-loaded my subconscious mind with lots of good examples, reviewing entire books of Monteverdi madrigals, directing a staged production of Ballo delle Ingrate, performing Orfeo, running a workshop on the Lamento and listening to live performances of Sfogava and other madrigals, in the three month period of thinking and composing. This time-period is comparable to Monteverdi’s speed of writing (although his work was often delayed by waiting for political and artistic decisions from his patrons). For the actual writing, I consciously employed techniques of cut-and-paste, pattern recognition, transformation, declamation and re-composition.

Cut and Paste

Monteverdi frequently uses precisely the same notes for particular words: the exclamation ohime! often falls from d to F# over an F# in the continuo bass. Where I recognised such words in Rinuccini’s libretto, I used the well-known formula. This procedure was applied only on the short term, usually a single word, perhaps a short phrase.

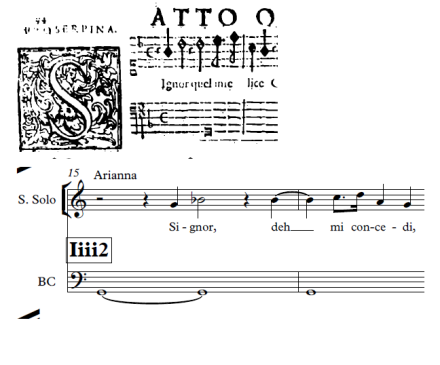

My setting of Arianna’s first speech borrows from Monteverdi’s setting of the same word as the opening speech for Proserpina in Act IV of Orfeo.

Pattern recognition

In the madrigal books, Monteverdi responds to texts that suggest (without necessarily citing precisely) verses he previously set, with music that recalls (without necessarily citing precisely) his earlier work. For example, the Lettera Amorosa with its paean to a woman’s red hair (La Florinda had red hair) frequently recalls moments from Arianna’s Lamento. Rinuccini’s libretto for the opera often suggests well-known texts, from his own work – Ballo delle Ingrate (also 1608), Euridice (1600) and the madrigal Sfogava con le stelle (1603) as well as from Striggio’s Orfeo (1607) and the Florentine Intermedi (1589). There are also very frequent cross-references within the libretto, with many parallel passages between Arianna’s Lament and the Nunzio’s description of her lamenting, Teseo’s meeting with Consigliero and the Pescatori’s report of that meeting, and images of sunrise and sunset.

Of course, there may well be other references that escaped me, and we cannot know how many references Monteverdi would have noticed, or chosen to act on. I deliberately took every opportunity I found to make use of this pattern recognition. My score may therefore have more (not necessarily precise) citations than Monteverdi’s practice, but Rinuccini’s libretto has more (sometimes subtle) citations than other early operas.

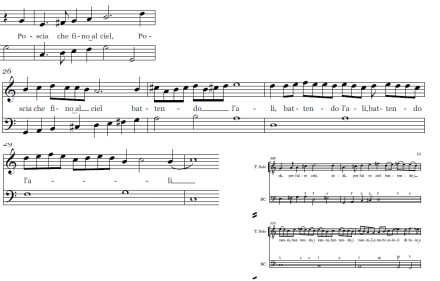

The words of Arianna’s Lament are referenced (in the previous scene ) by Nunzio Primo, and my setting follows Rinuccini’s lead.

This technique of pattern recognition I used on various time-scales, single words, complete phrases or extended sections, according to the length of Rinuccini’s citation. His reference to the opening solo of the Florentine Intermedi is unmistakeable, and I similarly cite the corresponding music in my setting of Nunzio Secondo’s final speech.

Transformation

There is, to my mind, an important distinction between modelling (my intention) and contrafactum (a valid approach, but not my choice). For both techniques, it’s important that if the listener recognises the original, any associations evoked will be thoroughly supportive of the new context. With this aim in mind, I modelled the opening Sinfonia of my Prologue on Monteverdi’s Tempro la cetra: both are songs for solo tenor, in which the singer’s lyre accompanies songs of love, not of war. I avoided direct copying by switching modes from Monteverdi’s “G major” to “G minor”, more suited to the opening of Rinuccini’s tragedia.

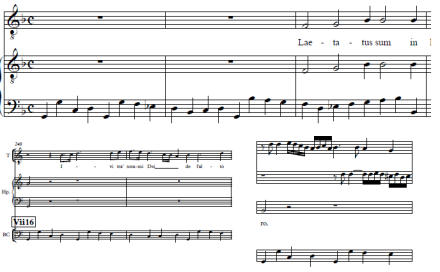

Similarly, I took the walking bass from Monteverdi’s Laetatus sum in the 1610 Vespers as a model for Bacco’s triumphant appearance, transforming it from sacred G minor to an exuberant G major, which ends up recalling Orfeo’s triumphant return from hell, Qual honor.

Cued by Rinuccini’s words Faran del tuo bel crin ghirlanda d’oro (They will make a golden garland of your hair), my violin-writing cites Monteverdi’s madrigal Chiome d’oro (Golden hair), which he himself borrowed from to set the Psalm Beatus Vir.

Declamation

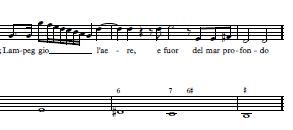

I declaimed aloud every single line of the libretto, searching for the best rhythms and pitch contours, accompanying my spoken recitation with historical gestures. I had not previously realised how significant the ‘language of gesture’ was for composers in this repertoire, as well as for performers. But Monteverdi’s letters, cited by Tim Carter, emphasise the need for strong gestures if there is to be good music, and Rinuccini’s libretto has Nunzio Secondo describe the silent eloquence of Bacco’s confrontation with Arianna. I had to correct my initial errors, and wrestle with challenging gesture-puzzles: lightning must strike downwards of course, but an emergence out of the deep sea must move upwards, yet somehow allow a low hand-position for the final word profondo. Once the gestures are decided, the music has to correspond.

Lampeggio l’aere, e fuor del mar profondo… (Lightning strikes through the air, and out from the deep sea…)

Out from the deep sea come Nymphs and Divas, whose music in my setting recalls the Nymphs coming out to dance in the Ballo Lasciate i monti (Leave the mountains) from Monteverdi’s Orfeo.

Re-composition

Although it is not specifically indicated in Rinuccini’s libretto, instrumental music is clearly required to delineate Act boundaries, to allow characters to enter or exit or as ritornelli between strophes of arias or choruses. Here, bolder compositorial action was necessary, since there was no text to inspire the modelling techniques described above. But the affetto (emotion) of the situation, and the identity of the characters onstage gives clear guidance: battaglia (battle) figures for Teseo and his Soldiers, pastoral recorders for the Pescatori (Fishermen), sad modes for Arianna. I wrote strophic variations on the romanesca ground for one chorus and imitated the extraordinary dissonances of Monteverdi’s madrigals for the Fishermen’s outburst of anger against Teseo Ma tu, superbo altero (But you, haughty and proud).

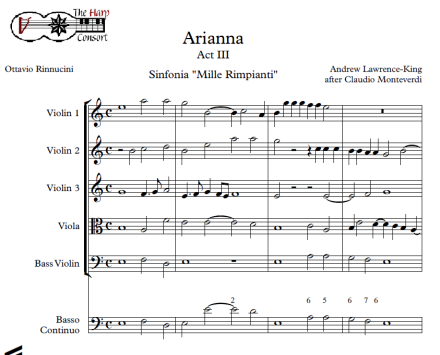

My setting of Arianna’s aria of hope Dolcissima speranza is modelled on Monteverdi’s well-known song Si dolce e’l tormento, and I rework that material again as exit music for the lamenting princess. In another sinfonia for the protagonist, I take the thematic material of Josquin’s 4-voice Mille Regretz (one of those earlier chansons which were remembered in the 17th century and performed in new, ornamented settings) and rework it as a polyphonic fantasia for string quintet in the style of Monteverdi’s prima prattica.

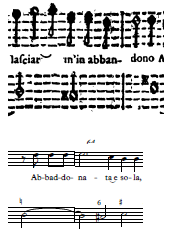

Perhaps the most delicate work was in Act IV Scene ii, where I had to compose new music for the commenting Pescatori as well as string accompaniments for Arianna herself, around the published music of Monteverdi’s Lamento. As a performer, I have always opposed the addition of editorial string accompaniments to basso continuo, so it was a strange experience to be tasked with writing such additional accompaniments myself. Modelling my work on Monteverdi’s string accompaniments to Clorinda’s speeches in Combattimento and on the last strophe of Possente Spirto in Orfeo, I gave Arianna the full complement of five strings (contemporary reports mention ‘violins and viols’ which probably means just small and large string instruments, but does suggest a full consort), but left sections with fast-changing harmonies to be accompanied by continuo alone. The resulting contrasts bring out both Arianna’s grandeur and her vulnerability, the essential elements of baroque tragedy.

Of course, the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and I eagerly await the reactions of performers and audiences as they experience for the first time in four centuries Monteverdi’s famous Lamento in its original scoring with strings, and in a historically informed operatic context.

Pingback: OPERA OMNIA – Music of the Past for Audiences of the Future | Andrew Lawrence-King

A fascinating project! But you should check bar 1 of the Sinfonia “Mille Rimpianti”. There is one thing that Monteverdi certainly wouldn’t have written. 😉

Dear Klaus, Thank you for your comment.

The Sinfonia “Mille Rimpianti” is a special case – as you will have recognised, it is based on Josquin’s well-known chanson “Mille Regretz”, the original being in a mode and 16th-century style little used by Monteverdi in his dramatic works. My take was to imagine Claudio making a 5-voice, seicento composition, citing Josquin’s work, employing Josquin’s points of imitation exclusively, but realising the polyphony in Monteverdian (rather than Josquin’s) prima prattica, bearing in mind that even the conservative polyphony of 1608 differs from its 16th-century models.

So this Sinfonia, at a moment of emotional intensity in Rinuccini’s drama, does indeed sound strange, and remote from Monteverdi’s normal idiom, whilst the original chanson would have been well-known to any musicians amongst the 1608 spectators. And where I have briefly cited Josquin, before applying Monteverdian transformations, it may well be that there is a bar that Monteverdi would not have written. My answer is to say “he didn’t write it, he cited Josquin.”

But I may also have made a misjudgement, or a mistake. So I’ll look again at this bar, before we record it.

And thank you for the comment. This kind of detailed, expert criticism is just what I hoped for, as a response to the project, and as a spur to improvements as the project continues to develop.

All best wishes, Andrew

Dear Klaus, And now I’ve looked, and you are quite right. There are parallel fifths between second violin and bass, which Monteverdi would not have wanted. And neither do I, so I’ll fix them. Josquin avoided the problem by having only 3 voices in the opening bars, and starting with a unison.

Artusi 1, Lawrence-King 0

🙂