1st November 2019:

To celebrate Orlando Orlando‘s being nominated for Russia’s highest theatrical award, the Golden Mask, in 6 categories – best production Georgij Isaakyan, best design Hartmut Schörghofer, best musical direction Andrew Lawrence-King, best lighting design Alexey Nikolaev , best female soloist Maria Mashulia, best male soloist Kiril Novakhatko – this article has been updated with additional commentary on Handel’s techniques of Drama & Dance-rhythms.

This article is posted in connection with the premiere of Handel’s Orlando at the Helikon Theatre in Moscow, 27th March 2019, entitled Orlando, Orlando: Handel’s Orlando (1733) in memory of the victims of the shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida (2016). Music by George Frideric Handel, Libretto adapted from Carlo Sigismondo Capece L’Orlando (1711) after Ludovico Ariosto Orlando Furioso (1516/1532). Concept & Adaptation by Georgij Isaakyan (Director), Edition by Andrew Lawrence-King (Musical Director), Techno episodes by Gabriel Prokofiev, Design by Hartmut Schörghofer.

Synopsis of Georgy Isaakyan’s version (read online and/or download pdf)

Orlando Orlando libretto (includes English translation: read online and/or download pdf)

This production is not an ‘authentic’ reconstruction of baroque opera, but a new work of music-theatrical creativity in which 18th-century music tells a 21st-century story, bringing together Gabriel Prokofiev’s specially composed electronic music and the most modern understanding of how George Frideric’s score would have sounded at the King’s Theatre, London in 1733.

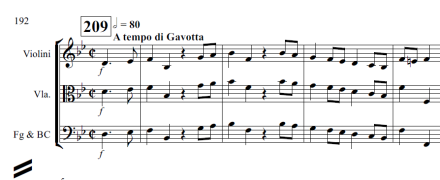

For Orlando, Handel assembled an unusually large orchestra with a powerful bass-section, and the dance-rhythm of the fashionable Gavotte is heard several times, representing Orlando’s fury.

In his madness, Orlando identifies Angelica as the mythological godess Persephone: “Beautiful eyes, no, do not weep, no”

In his madness, Orlando mistakes Dorinda for the goddess Venus, or an enemy warrior: “Already, I wrestle him; already I embrace him with the force of my arm”

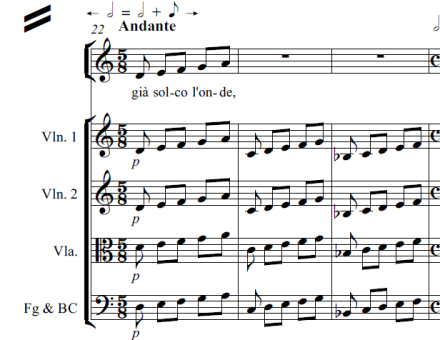

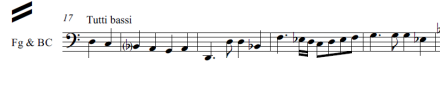

In the extraordinary mad-scene created for the famous Italian castrato Senesino, bass instruments play alone as the protagonist descends into a hell of jealous rage.

“I am my own spirit, cut off from myself. I am a ghost, and like a ghost I want to make the journey down there to the kingdom of sorrow!”

And the full orchestra lurches into 5/8 metre as Orlando imagines himself rowing Charon’s boat into the underworld.

Handel freely borrowed from other composers’ (and his own) work, and the previous season he re-wrote two earlier dramas, expanding the chamber-opera Acis & Galatea and transforming a one-act staged masque into the first English oratorio, Esther, performed as a three-act concert with the addition of solo harp, trumpets, drums and a chorus. For Orlando, Handel adapted Carlo Sigismondo Capece’s (1711) story of mad jealousy, itself a re-working of episodes from Ariosto’s 16th-century classic, Orlando furioso. Bernard Picart’s (1710) engraving of the giant Atlas, republished in 1733 as Le Temple des Muses, was re-interpreted as the stage set for the opening scene with the magician Zoroastro.

Handel’s audience were thrilled by several spectacular stage transformations, utilising the full resources of period stage machinery and dramatically presented as the result of Zoroastro’s magic, assisted by his demons. In our production, Schörghofer’s design employs modern stage technology to offer the audience surprise and spectacle, whilst clarifying the subtly interwoven stories as characters from medieval romances (Chanson de Roland, 11th cent) are re-drawn by Boiardo (Orlando innamorato, 1495) Capece, Handel and Isaakyan.

A German musician producing Italian opera in England, Handel writes a conventional French-style overture, but surprises the audience with up-to-date dance-music, a fast Italian giga.

This Italian giga has characteristically continuous movement in the melody line, with a driving bass.

The rhythmic drive of the giga is disrupted with broken phrases to depict Dorinda’s misplaced faith in ‘sweet little lies’.

In spite of trills and rests, this Aria still shows the characteristics of an Italian giga: “Oh dear little words, sweet glances; even if you are lies, how I will believe you!”

The step-and-jump rhythms of a French gigue are heard in Medoro’s second Act aria;

The restrained movement of a French gigue characterises Medoro’s hesitation: “I would like to be able to love you, but…”

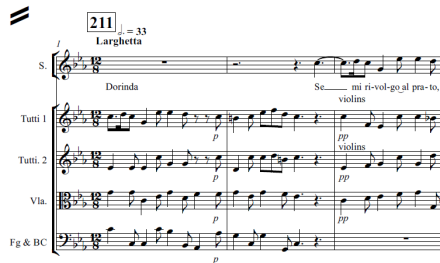

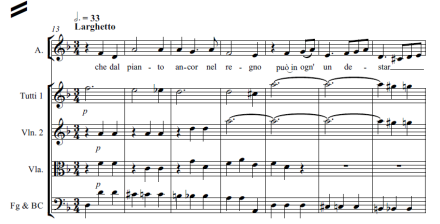

the slow swing of an Italian folk-dance, the siciliano characterises Dorinda’s wistful longing;

More gentle than a giga, the tender siciliano characterises Dorinda’s nostalgia for a love that never was: “If I return to the meadow, I am made to see my Medoro in every flower”

Orlando’s lament in hell is sung to a French passacaille.

In French operas the descending bass of the minor-mode passacaille suggests tragic passiona and creates opportunities for expressive dissonances and chromatic variations: “For from tears even in the kingdom of Hell, pity can be aroused in everyone”. The audience come to realise that this text is ironic: in his madness, Orlando shows no pity for Angelica, and changes his Gavotte-refrain to “Yes, eyes, weep, yes, yes!”

The composer’s bold strokes of dramaturgical re-designing and contrasting musical styles were further transformed by unwritten baroque performance practices. Continuo-players spontaneously realised the written bass-line with rich harmonies and strong rhythms; singers added their own variations to the repeated section of a da capo aria; sometimes time would stop whilst singers or instrumentalists improvised a final cadenza. Handel did not conduct, but directed by playing the harpsichord, alongside the theorbo (bass lute). The expression of the vocal line was not indicated with markings of piano and forte, but follows from the accentuation and emotions of the words.

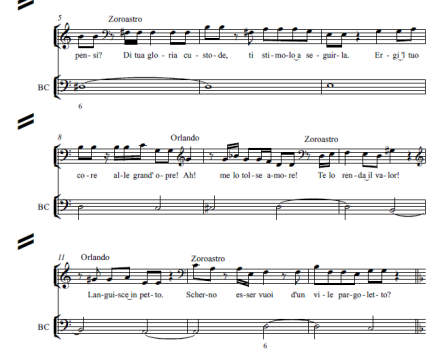

This Recitative is not just rapid patter, look at all the rhetorical detail: A long note and glorious high notes for “As custodian of your glory…”. Strong dissonance for “I stimulate you to follow it”. Another long note for “Urge.. ” and the highest notes and thrilling contrasts of short notes for “…your heart to great works!”. A long sigh “Ah!” with an intake of breath afterwards, dissonance and Orlando’s voice dropping “love takes it all away from me”. Zoroastro’s voice rises with long notes and an unexpected sharp in the melody-line for “It will be given back to you by valour!”. Orlando’s falling phrase (which would be given the conventional drooping appoggiatura) “It languishes in my breast”. Zoroastro’s strong retort with high notes “Scorned…”, snappily broken phrases “is that what you want to be…” and a suitably horrible melodic tritone “by a vile little boy?”. The “little boy” is Cupid as the flute’s flapping wings show in the following bars.

Instrumentalists similarly have few written phrasing-marks, but imitate the crisp articulation of the Italian language with a great variety of bow-strokes.

What might appear to be just a series of equal quavers acquires subtle rhythmic patterning from the long/short, accented/un-accented syllables of the Italian text, imitated in this English-language metrical paraphrase: “Respond to it for me; your heart might tell you that.. I discard all your love”. Today’s performers might usefully channel a jazz-singer’s approach to text and rhythm, rather than classical training.

For the eerie calm of Orlando’s final aria we added baroque harp, which in Handel’s dramatic works suggests a vision of heavenly peace. Trumpets and drums represent royal authority and military power; horns and oboes a pastoral idyll; the flute an amorous nightingale or Cupid’s fluttering wings. Modern scholarship has revealed the subtle structure of Handel’s recitatives, which imitate the pitch contours and speech rhythms of a great actor in the baroque theatre.

Studying the text as dramatic speech in the grandiose style of baroque spoken theatre reveals how accurately Handel notates [what Il Corago first described c1630 as] ‘the declamation of a fine actor’, in the generation between Thomas Betterton and David Garrick. As shown in my English-language metrical paraphrase: Zoroastro barks out his anger with the urgency of poetic anapests followed by the characteristic contrast of short and long notes “To what risks you’re exposed now, you reckless lovers, by blinded love!”. Angelica’s reply is a languid drawl “We only have to get free from Orlando.” Zoroastro barks again with the upward intonation of an abrupt question “And if he comes here?” – singers can appropriately add an upward appoggiatura. Medoro tries to assert himself, but Handel’s downward inflections betray the character’s weakness “My heart is also valiant!” and Angelica interrupts with powerful rhythm and a strong upward leap “P’haps for my sake, he would not be so cruel” – the conventional appoggiatura makes a harsh dissonance here. Zoroastro mimics her phrase with the slow tempo of bitter sarcasm “And he’ll be nice… to his unfaithful lover?”. With a wonderfully dramatic contrast, he switches back to fast anapests “Hurry up and get running, fly away from his anger…”. The notated rhythms of Handel’s music work perfectly as dramatic speech.

See my previous article on tempo and rhythm for Handel, here.

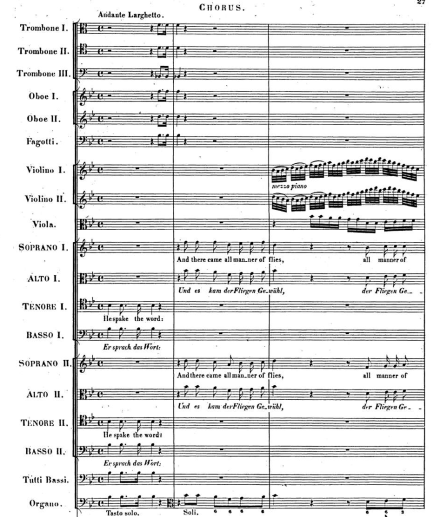

We added a chorus, whose members (in the manner of Handel’s oratorios or Bach’s Passions) comment on and drive forward the events of which, in the end, they are the victims. Their music is borrowed from Handel’s drama of cultural identity and religious conflict, Israel in Egypt (1739): Handel himself re-worked one of these choruses for Messiah (1741).

In Isaakyan’s reworking of the story, the magician Zoroastro appears in different guises, always as an authority figure: a star news-presenter, a domineering father, a bible-preacher, a populist politician. The choruses I selected show the public’s various reactions: unchallenging acceptance “Great was the company of the preachers”; anxious forboding “The people shall hear and be afraid… they shall be as still as a stone”; belated understanding “There came a thick darkness”; and a fascination with destructive power “He gave them hailstones for rain, fire mingled with the hail”.

“Orlando Orlando” Premiere Left to right: Hartmut Schörghofer, Gabriel Prokofiev, Georgy Isaakyan, Andrew Lawrence-King, Dmitry Bertman