This article, published in shorter form as the introduction to a concert streamed online, discusses the current relevance of Baroque affetti [emotions] and the Rhetorical aims of delectare, docere, movere [to delight, to teach, to move the Passions].

Concert listings, song texts & translations

Online Concert

The link to the concert may become temporarily unavailable, whilst the recording goes through post-production. And new concerts in the series may appear at the top of the broadcaster’s list. I hope to provide a permanent, direct link, soon.

Scherzi Musicali

Italian Baroque Music: Monteverdi, Vivaldi, Corbetta, Handel

“That smile heals me…”

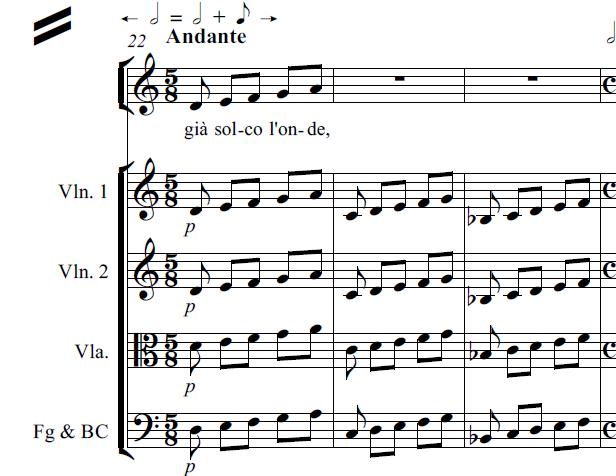

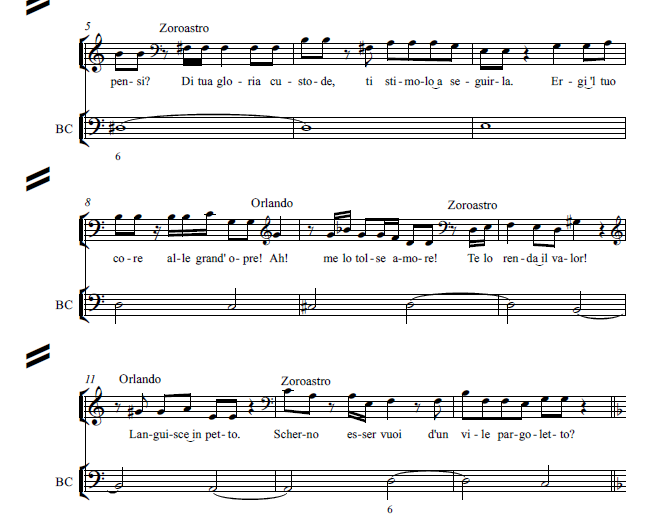

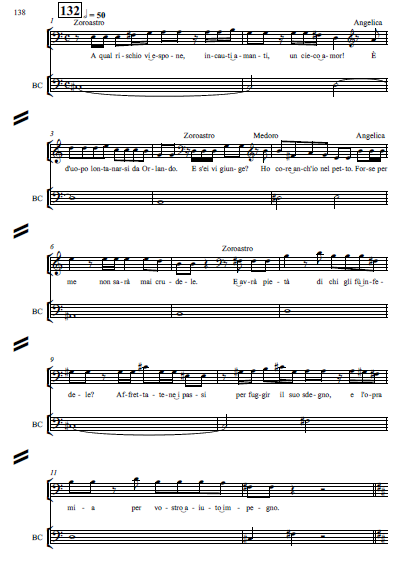

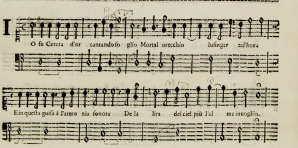

Monteverdi’s musical fun – scherzi musicali – and beautiful arias – ariose vaghezze – are offered to the public in music-books printed by Bartholomeo Magni in Venice almost four hundred years ago. These are not madrigals requiring an ensemble of singers, but solo songs with basso continuo accompaniment which could be realised on any instrument: harpsichord, lute, guitar, baroque harp. Composed during the time of the very first ‘operas’, these minatures appeal to the emotions as theatrical fragments, instantly recognisable dramatic scenes.

Affetti

But that emotionality is subtly different from the Romantic ideal of an artistic genius, expressing with ever-greater intensity a sublime feeling, that will impress and even overwhelm his audience. Rather, Baroque music contrasts ever-changing emotions and seeks to move your passions, as La Musica proclaims in Monteverdi’s Orfeo:

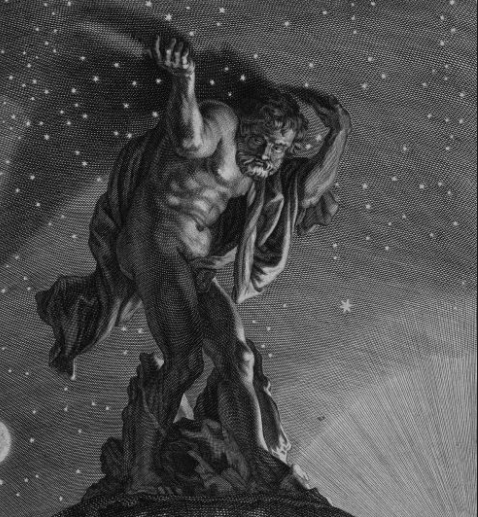

Accompanied by the golden harp, my singing

can always charm mortal ears for a while.

And in this way, with the sonorous harmony

Of the lyre of the cosmos, I can even move your souls.

Read more: The Philosophy of La Musica

Read more: contrasts of affetti in the ‘first opera’

The ‘lyre of the cosmos’ represents the mysterious power of music. In metaphors of Cupid’s love-arrows and stormy seas of passion, we see poetic images as depicting real emotions. And no doubt, listeners can find in these verses from Shakespeare’s time words that still speak to us today: sanatemi col riso…

Heal me with a smile…

The renaissance Science of emotions models the Senses (in this case, eyes and ears) taking in the energia (energetic spirit) of a performance (delivered by Rhetorical actio) and the coordinated affetti of music and text (delivered by Rhetorical pronuntiatio), to create ever-changing Visions in the mind. These Visions send energia down into the body, producing the physiological changes associated with changing pyschological emotion. Mind, Body and Spirit exchange energia, so that thoughts, (spiritual) emotions and (physical) feelings are interconnected – ideally, in Harmony.

Rhetoric: structure & contrasts…

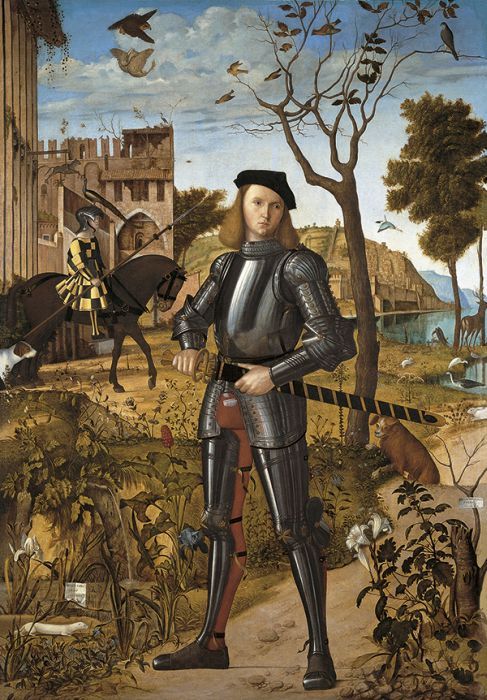

For Monteverdi, an aria is not just a nice tune, it is a repeating structure of poetry, rhythm and harmony, on which words and music make elegant rhetorical variations. The dramatic situation is understood: the poet is in love, the beloved is ‘cruel’; the poet is wounded by the arrows of love, but the beloved’s smile can turn his prison into paradise. The rhetorical appeal is to the mind and the heart, as well as to the ears. The emotional power is embedded in contrasts: in Tempro la cetra the poet tunes his lyre to sing of War, but it only resounds with Love.

Tempro la cetra, e per cantar gli onori

di Marte alzo talor lo stil e i carmi.

Ma invan la tento e impossibil parmi

ch’ella già mai risoni altro ch’amore.

Così pur tra l’arene e pur tra’ fiori

note amorose Amor torna a dettarmi,

né vuol ch’io prend’ ancora a cantar d’armi,

se non di quelle, ond’egli impiaga i cori.

Or l’umil plettro e i rozzi accenti indegni,

musa, qual dianzi, accorda, in fin ch’al canto

de la tromba sublime il Ciel ti degni.

Riedi a i teneri scherzi, e dolce intanto

lo Dio guerrier, temprando i feri sdegni,

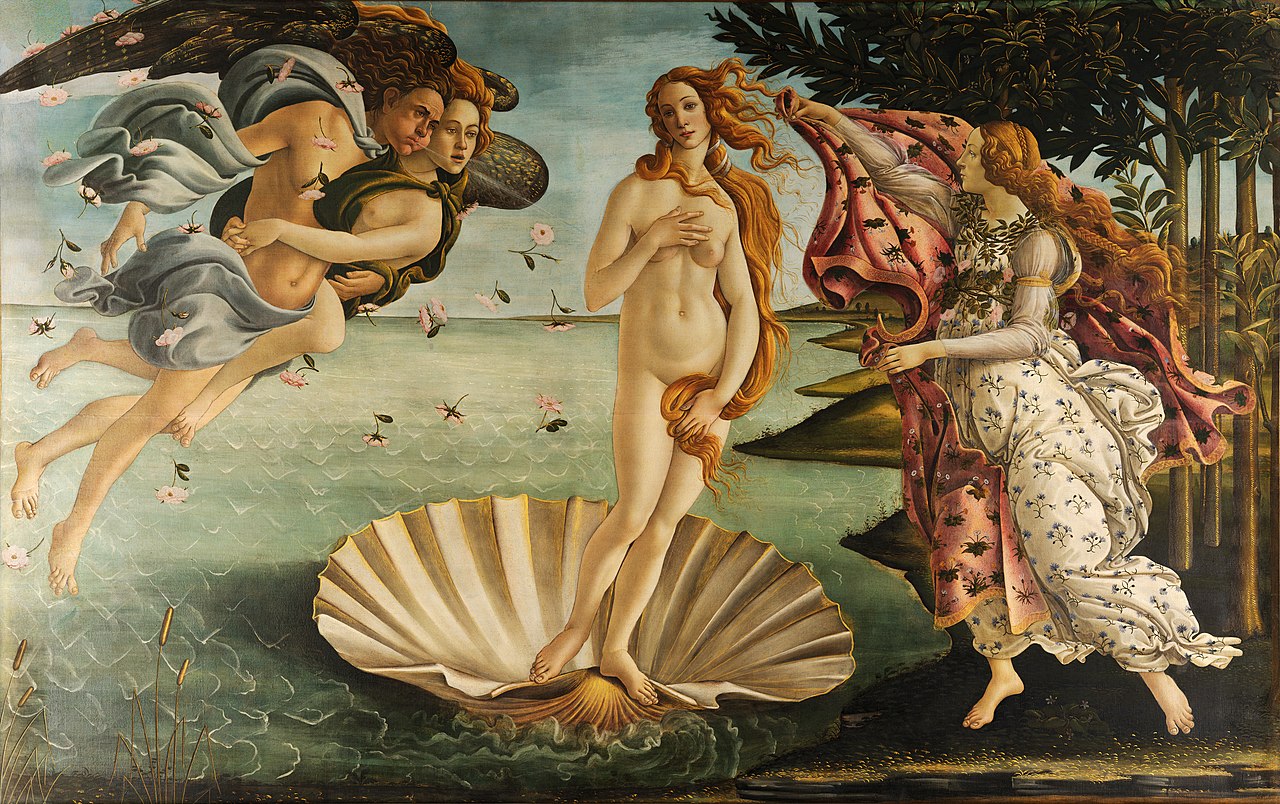

in grembo a Citerea dorma al tuo canto.

I tune the lyre, and to sing the honour

Of Mars, now I raise my style and my song.

But in vain I try, and it seems impossible

That it will ever resound except with love.

Thus in the arena itself and just amongst flowers

Amorous notes Love returns to dictate to me.

And does not want me to start to sing of arms again,

Unless of those, with which Cupid wounds hearts.

Now, the humble plectrum and the unworthy, broken accents

Muse, as before, tune them, so that to the song

Of the sublime trumpet Heaven honours you.

Come back to tender games, and sweetly for a while

The warrior God, tempering his fierce anger,

In the lap of Venus will be lulled to sleep by your song.

Contrasts of affetti were categorised by the renaissance concept of the Four Humours: Sanguine (love, courage, hope), Choleric (anger, desire), Melancholy (careful thought), Phlegmatic (unemotional). Throughout this poem, Sanguine love is contrasted with Choleric war. Ideally one’s humours would be balanced, tempered. Poetic and musical composition are usually characterised as works of the careful (and care-full) concentrated inward thought processes of Melancholy, whereas performance, directed outward, is often Sanguine. In this poem the Melancholy art conceals itself – ars celare artem – and in the lap of Sanguine Venus, Choleric Mars surrends to the power of music and is lost in Phlegmatic sleep.

This piece, and renaissance Philosophy in general, links period medical science (the Four Humours) with metaphysics (the Music of the Spheres), and to the artistic principle of contrasting affetti. The Science of the Music of the Spheres (musica mondana) connected that perfect movement of the heavens with the harmonious nature of the human being (musica humana) , and with actual music (musica instrumentalis) played or sung. The contrasts of the third stanza are of Earth and Heaven: the humble, unworthy accents of musica instrumentalis will finally find accord with the sublime song of the Last Trumpet – musica mondana.

Supported by this philosophy, classical mythology is made to work as a metaphor for Christian doctrine. The implication is that the poet/singer himself will also be redeemed, as his own nature (musica humana) ‘resounds’ to the music of the Spheres.

…for mind (docere)

Ohimè, ch’io cado begins with a firmly constructed ‘walking bass’, but the singer crashes in with a downward plunge: the poet has fallen head-over-heels in love, just when everything seemed to be safe. Images and emotions are presented in clever contrasts: ‘the withered flower of fallen hope’ and ‘the water of fresh tears’; the ‘would-be warrior’ is ‘now a coward’ who cannot withstand ‘the gentle impact of a single glance’. The poet’s attempt at Choleric sdegno (anger) is easily diverted to a Sanguine love-paradise.

… heart (movere)

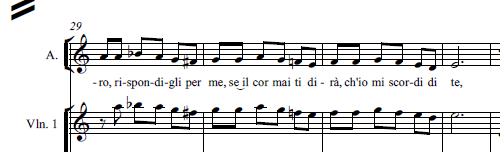

Over a descending bass-line, Si dolce ‘l tormento juxtaposes contrasts even more closely, to sway the listener’s emotions line by line: sweet torment, happy, cruel, beauty, ferocity, mercy, a wave-swept rock – all this in the first strophe alone! As the momentary affetti swirl around, the minor mode, tender dissonances and descending bass communicate a pervasive sense of Melancholy.

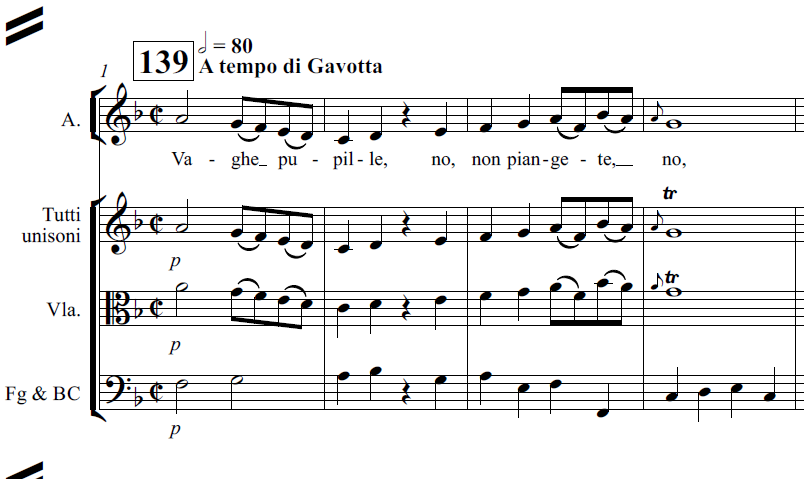

…and ears (delectare)

That glance from the lover’s eyes – Quel sguardo sdegnosetto – is no real threat: we might paraphrase the first line as “You’re so cute when you’re angry!” And the bass-line variations on the ciacona dance reveals that the lovers are fooling around, playing risqué party-games: “When I die, your lips will quickly revive me”.

In this song, contrasts of affetti are perhaps less cerebral, less melancholic, but rather charming and delightful, and the pervasive mood is Sanguine. There is little doubt that the poet is confident that his hopes of love will be enjoyed!

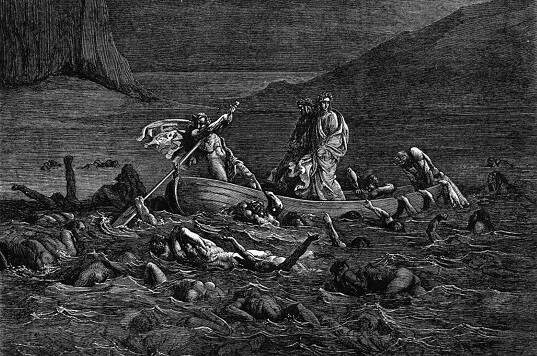

Come Hell or High Water

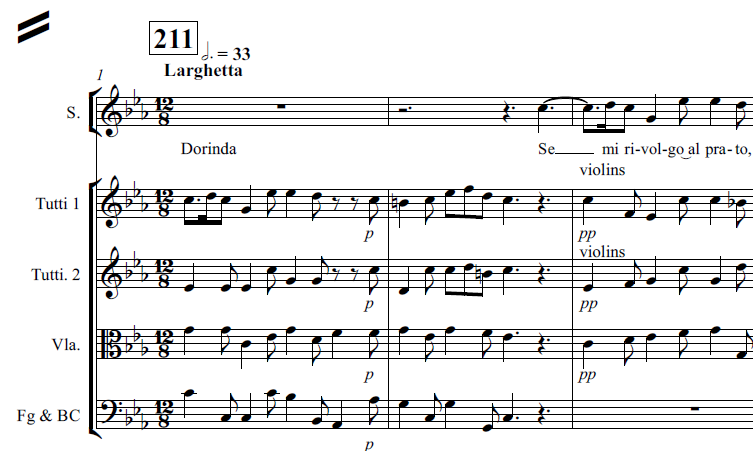

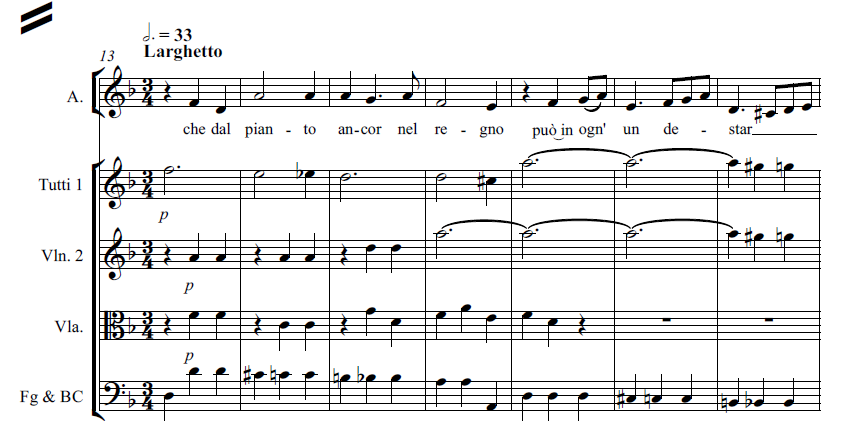

Baroque contrasts can be extreme: In the Ballo delle Ingrate women emerge from the ‘wild, hot prison’ of Hell, to take a brief respite in the ‘serene, pure air’ of the upper world.

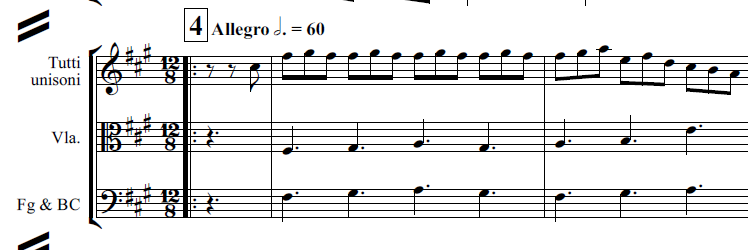

The furore of divine anger provides an excuse for Vivaldi’s favourite seasonal storms, tempered by the calm of clemency, but returning with the delicious inevitability and ornamental surprises of the Da Capo Aria. A Recitative makes it personal: “Spare me, sad and languishing”. The central Aria, with its contrasts of fletus… laetus (weeping… happy), corresponds to the slow movement of a violin concerto, with an Alleluia as the virtuosic finale.

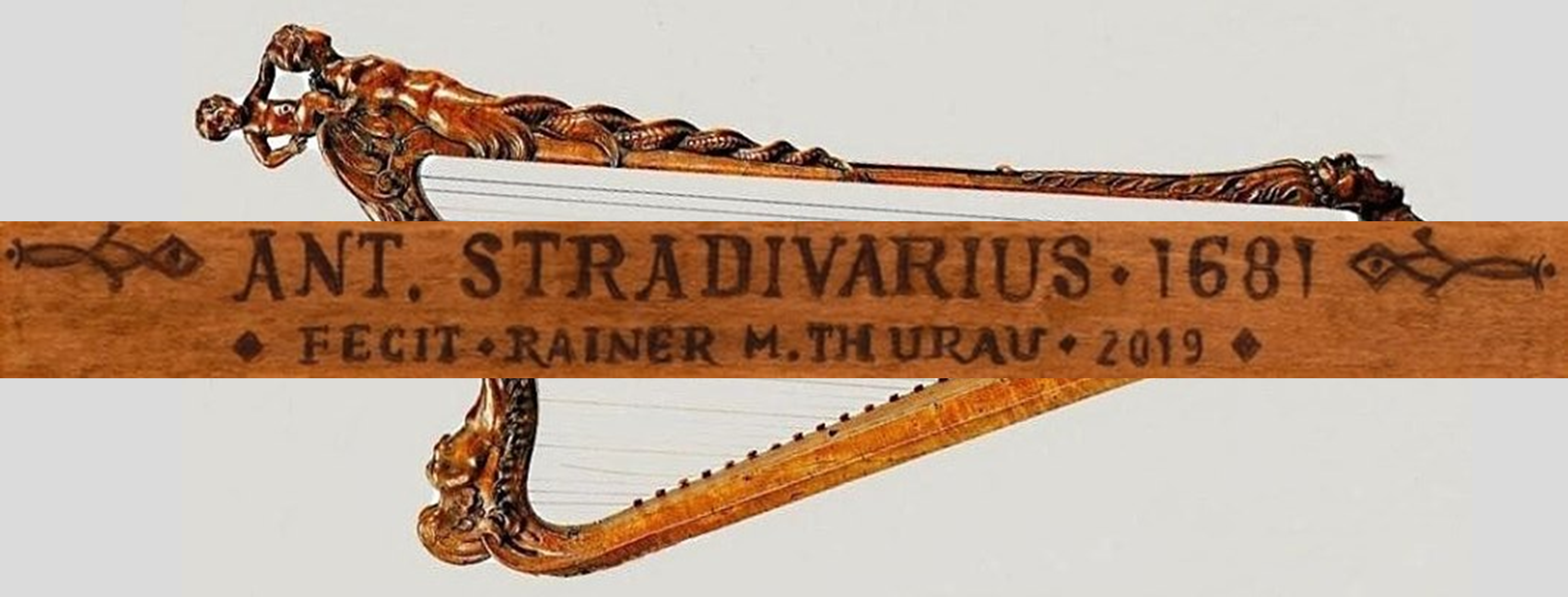

The instrumental compositions that follow are variations on descending bass-lines. The fun of Corbetta’s Caprice, played on a modern copy of the Stradivarius Harp (1681, the year of Corbetta’s death) more about Rainer Thurau’s Strad Harp here, lies in its contrast of the gentle nobility of the French chaconne with the more energetic celebrations of an Italian ciacona.

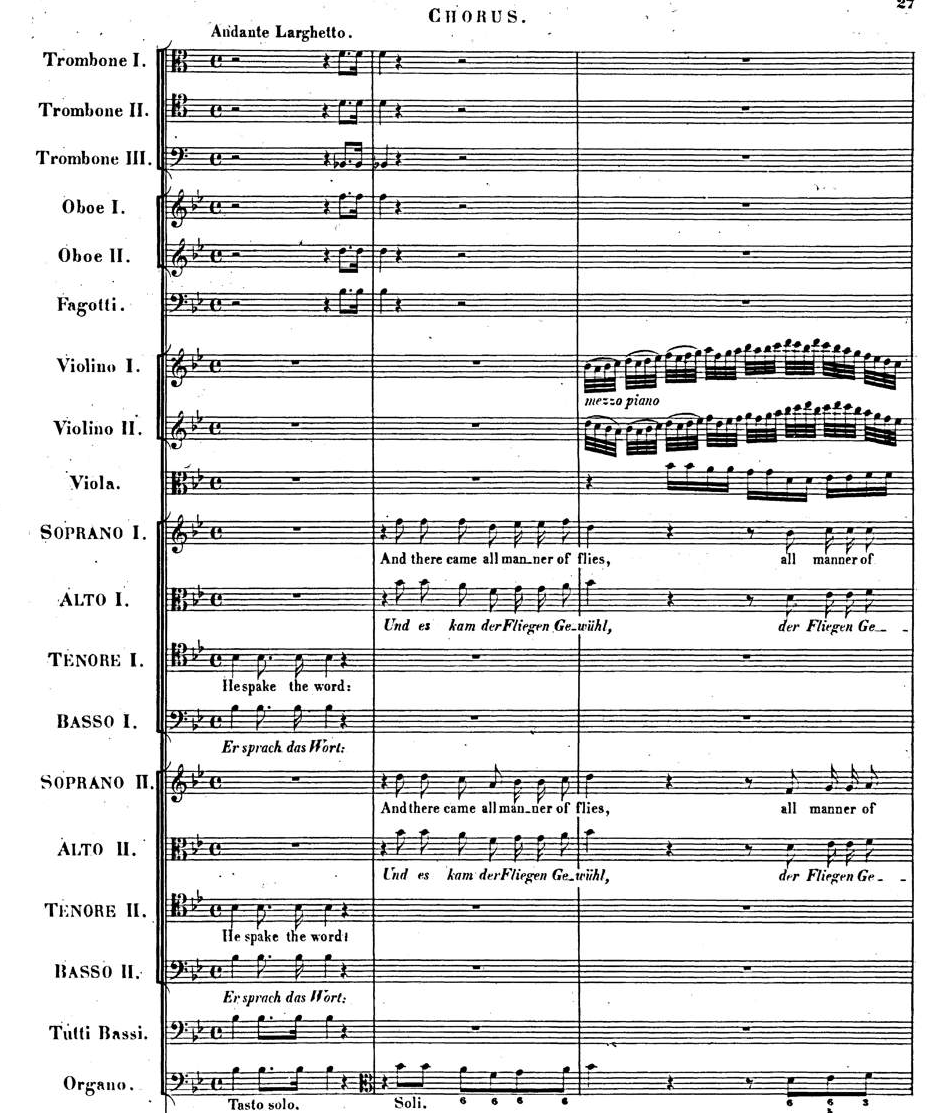

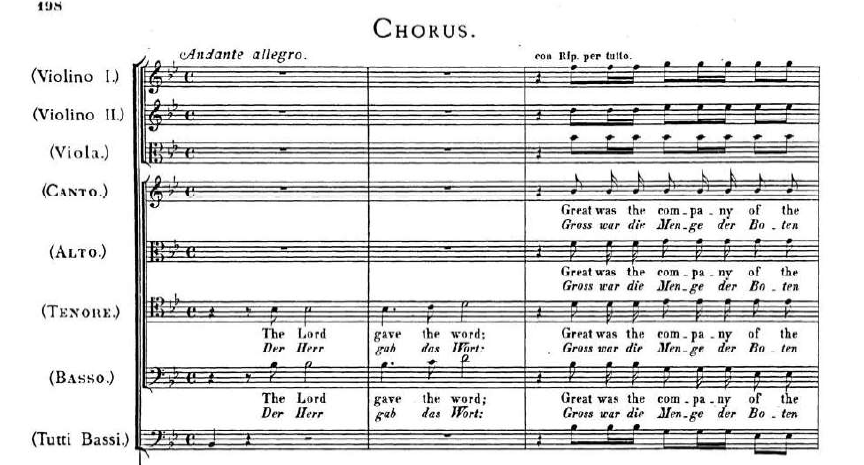

Handel’s Andante, with its variations on a walking-bass, was published posthumously as an Organ Concerto. A Baroque listener described how the composer would improvise an introduction to the concerto, with a polyphonic fantasia “which stole on the ear in a slow and solemn progression.”

A fine and delicate touch, a volant finger, and a ready delivery of passages the most difficult, are the praise of inferior artists: they were not noticed in Handel, whose excellencies were of a far superior kind; and his amazing command of the instrument, the fullness of his harmony, the grandeur and dignity of his style, the copiousness of his imagination, and the fertility of his invention were qualities that absorbed every inferior attainment.

When he gave a concerto, his method in general was to introduce it with a voluntary movement on the diapasons, which stole on the ear in a slow and solemn progression; the harmony close wrought, and as full as could possibly be expressed; the passage s concatenated with stupendous art, the whole at the same time being perfectly intelligible, and carrying the appearance of great simplicity. This kind of prelude was succeeded by the concerto itself, which he executed with a degree of spirit and firmness that no one ever pretended to equal.

Sir John Hawkins General History of the Science and Practice of Music (1776)

Iconographical coding characterises Handel as composer (pen and scores), performer (keyboard) and – unmistakeably – as Melancholy (head leaning on left hand).

Handel’s Messiah and that glorious Aria of Sanguine hope, Rejoice greatly, need no introduction. But in Jennens’ carefully chosen biblical excerpts the characters of the Daughter of Sion and the Heathen are also coded symbols for the politics of the Hannoverian monarchy, of another King who “cometh unto thee”. So whether or not we can identify with the rejoicing daughter, the Messiah offers Peace for those who believe differently.

Rhetorical Structure: architecture & building blocks

From Monteverdi’s and Vivaldi’s Venice to Handel’s London, the grand architecture of Baroque music adopted a variety of fashions. But the building blocks remained similar: the sighing slurs of Vivaldi’s calms also create Handel’s peace; bass-lines still walk steadily; a jump in the melodic line always makes the heart leap, whether falling in love with Monteverdi, or rising to rejoice with Handel. And the ancient power of Music’s rhetoric still charms the ears, communicates between minds, and consoles your hearts.