Time is what gives being to Music

Il tempo dunque è quello che da esser alla Musica. Zacconi Prattica di Musica (1596) Chapter 30.

Rhythm is life.

Paderewski Tempo Rubato (1909)

Many musicians and listeners might agree that rhythm is the life and soul of Music, whilst holding quite different opinions as to what kind of musical time is so essential.

- “Just give that rhythm everything you’ve got”

- “It’s got a back beat, you can’t lose it”

- “Emotion excludes regularity. Tempo Rubato then becomes an indispensible assistant”

- “Above all things, keep the Equality of Measure”

- “Time, like an ever-rolling stream…”

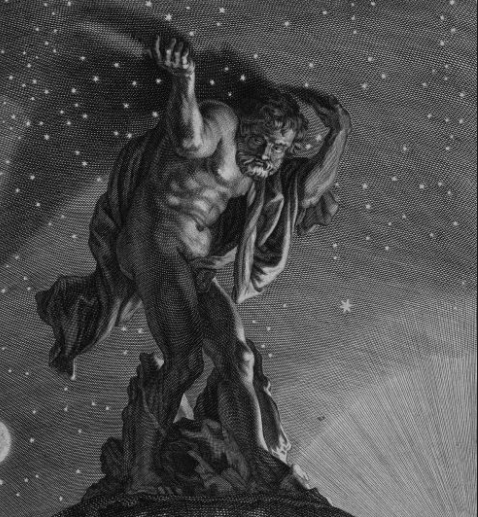

- “Time is a number of motion, in respect of before and after”

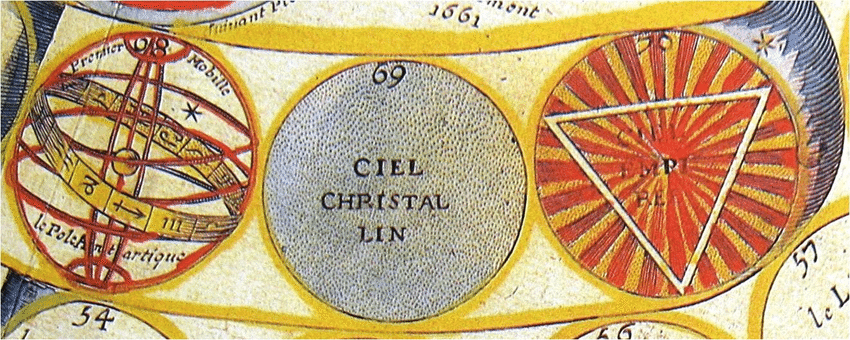

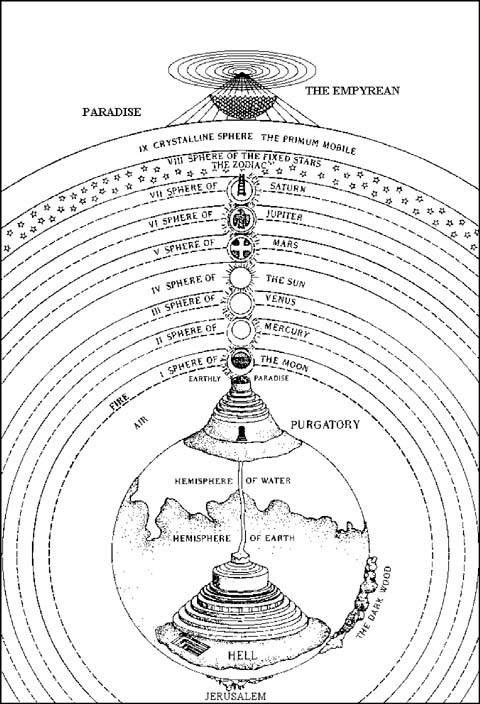

- “Time is the space demonstrated by the revolution of the Primum Mobile”

- “Absolute, true and mathematical time, of itself, and from its own nature flows equably without regard to anything external”

… li cieli, li quali continuamente si girano … sono nove, come di sopra è stato ditto; cioè VII cerchi di sette pianeti e l’ottavo de le stelle fisse dov’è lo zodiaco, e lo nono che è lo primo mobile. E queste revoluzioni sono quelle che dimostrano lo tempo: imperò che tempo non è altro che lo spazio, nel quale queste revoluzioni si fanno; e questo spazio produce Iddio dal suo essere eterno. Buti Commentary on Purgatorio 24: The heavens, which revolve continuously… are nine, as has been said above; that is 7 circles of seven planets and the 8th of the fixed stars, where the Zodiac is, and the 9th is the Primum Mobile. And these revolutions are what show time; therefore time is nothing other than the space/interval within which these revolutions are made; and this space is produced by God from his eternal being.

Texts from classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages – Dante, Aristotle and Buti – still provide the primary definitions of Tempo in successive editions of the Vocabulario of the Accademia della Crusca from 1612 to 1748.

- Irving Berlin It don’t mean a thing, if it ain’t got that swing (1931)

- Chuck Berry It’s gotta be Rock ‘n’ Roll music (1957)

- Ignacy Jan Paderewski Tempo Rubato (1909)

- John Dowland Micrologus (1609)

- Isaac Watts Oh God, our help in ages past (1708)

- Aristotle Physics (4th cent. BC)

- Francesco di Bartoli da Buti Commento sopra la Divina Commedia di Dante (end of 14th cent.)

- Isaac Newton Principia (1687)

Newton’s (1684) MS notebook for De motu corporum in mediis regulariter cedentibus defines Tempus Absolutum three years before the fuller definition in Principia. But the text made famous by the first English translation of Principia by Andrew Motte only appeared much later, in 1729.

So when we read from many Baroque writers [heartfelt thanks to Domen Marincic and others who sent me numerous citations of this concept] that

Time is the Soul of Music

– from Zacconi writing in 1592 (published in 1596 as Prattica Book 2, Chapter XV, folio 95v): il Tempo….essendo egli nella Musica quasi l’anima [Time… being in Music like the soul] and (Book 2, Chapter III) Il tatto non è altro che il Tempo in esser presente [Tactus is none other than Time in actual presence] to the Biblioteca Universale sacro-profana antico-moderna (1704): la Battuta è la misura, e quasi l’anima della Musica [the Beat is measure, and like the soul of Music] –

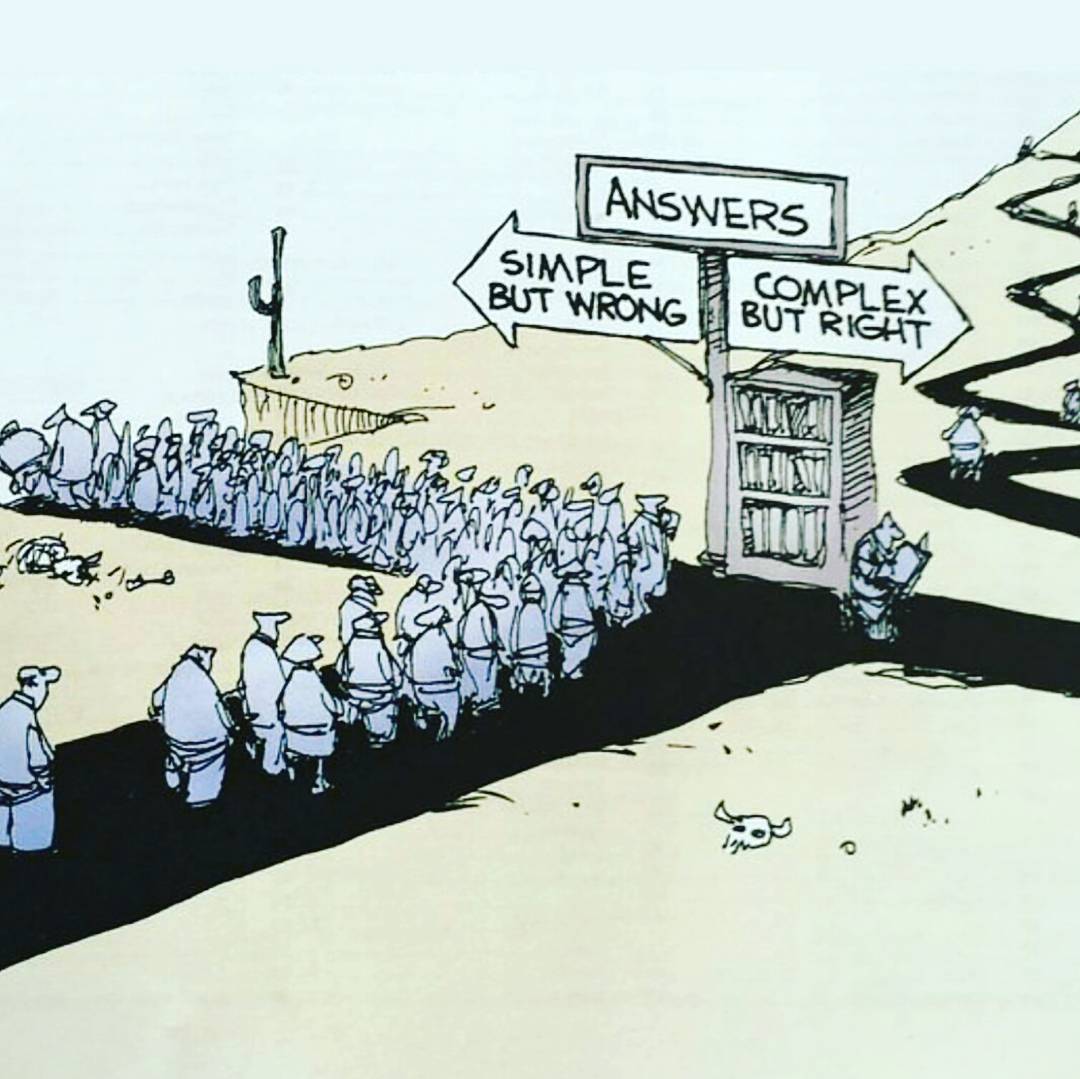

we must be on our guard that all three terms lead us into complex semantic fields (Time: tempo, misura, battuta, tatto; Soul: anima, animo, mente, cuore; Music: mondana, humana, instrumentalis, arithmetica) where technical definitions and everyday understandings have shifted over the centuries. Aristotle’s motion-driven Time (which was still the common understanding in mid-18th-century Italy) is not the same as Newton’s Absolute, Mathematical Time, any more than our own intuitive sense of everyday Time corresponds to Einstein’s Relativity or Hawking’s Imaginary Time.

Tactus is the Soul of Music

Nevertheless, two writers from different countries and periods give strikingly similar descriptions of Tactus, showing a strong continuity from the 16th to the 18th centuries, and a noticeable differences from modern practice.

Venice 1592

Sotto il tatto si pone questa figura & quella, & per questo si dice che l’harmonia nasce dalla consideratione di diverse figure sotto una determinata quantita di Tempo constituite (Zacconi Prattica Book 1 Chapter 29 Del Tempo Musicale & delle sue divisioni): Under the Tactus you put this note and that, and by this we say that harmony is born from the consideration of various notes organised within a certain amount of Time.

Halle 1789

Der Takt… ist eine Anzahl von Noten in einen gewissen Zeitraum eingetheilt (Türk Klavierschule Chapter IV Vom Takte): The Tactus … is a number of notes organised into a certain amount of Time.

Semantic Fields

For both writers, the term they are trying to define has a wide and rich semantic field. Time ~ mensuration Sign; Tactus; Measure of duration; Rhythm, i.e. the division of time into note-values, written and performed; a specific note-value; the act of beating time and the Beat itself; speed; Metre.

Venice 1592

Tempo: il quale si forma con un segno che ne da inditio… dal tatto che è la misura (Chapter 28) Time [mensuration sign of Tempus]: which is formed by a Sign that indicates the Tactus and the Measure.

Il tatto e quando dal Tempo in atto le vengan misurate, & che si cantano… il Tatto occupase tutto un Tempo… il Tempo essendo atto a diverdersi (Chapter 30 Del origine del Tempo) The Tactus is when [the note-values] are measured in real Time and are sung. The Tactus occupies a complete [unit of] time… Time [Rhythm] is action of dividing [the note-values]

Se per vigor di segno vanno due Semibreve al tatto, over due Minime (Chapter 33 Del division del tatto & sua sumministratione) [A specific note-value] Whether according to the Sign two semibreves go to the Tactus, or two minims. [ALK: In the late 16th century, identification of equal Tactus with the breve, i.e. down for one semibreve, up for the second semibreve, was being replaced by identification with the semibreve, i.e. down for one minim, up for the second minim, with triple metre proportions replacing tempus perfectum. The difficulty of reconciling older theory and notation with new practices accounts for much of the confusion about proportional notation in the early baroque period.]

Onde si come il tatto si divide, nel equale & nel inequale; cosi essi segni contenuti sotto questo nome di Tempo si dividano nel perfetto, & nel imperfetto. (Chapter 29) So just as the Tactus is divided into equal (duple metre) and unequal (triple metre); so these Signs included under this term Tempus are divided into perfect (triple) and imperfect (duple).

Piu tatti possano essere quali piu presti, & quali piu tardi, secondo il loco, il tempo, & l’occasione (Chapter 33) [Speed] Different [ways of beating] Tactus can be faster or slower, according to the place, the time and the occasion.

Le misure alla fine non son altro che quantità di tempo (Chapter 30) Measures finally are nothing else than amounts of Time [duration]

Quelli intervalli Musicali che sotto il Tempo si misurano… in dua modi… Il modo occulto Modo occulto è quello con cui componendole il compositore le misura & fa che gl’intervalli di tutte la parti correspondino in uno… Il modo manifesto puoi è quello quando le si cantano. (Chapter 29) Those musical durations which are measured by Time in two ways: the hidden [notated] way is whilst composing them, the composer measures them and makes the durations of all the parts correspond in unity; the revealed [performed] way then is when they are sung.

L’attione o l’atto che si fa… alle volte si chiama tempo, alle volte misura, alle volte battuta et alle volte tatto (Chapter 32 Che cosa sia misura, tatto, & battuta) The action [beating Time] which is actually done… is sometimes called Time, sometimes Measure, sometimes Beat and sometimes Tactus.

Halle 1789

Takt… die Noten, welchen in einem einzigen, zu Anfange des Tonstückes bestimmten Zeitraume enthalten, und zwischen zwey Stricken eingeschlossen sind. [Mensuration Sign & notation of rhythm]: the notes contained in a single amount of time [duration], specified at the beginning of the piece [sign], and enclosed by two lines [bar-lines].

Unter Takt, in sofern von der Ausübung die Rede ist, versteht man daher gemeiniglich, die richtige Eintheilung einer gewissen Anzahl Noten &c, welche in einer bestimmten Zeit gespielt werden sollen. Tactus, when we talk about performance, is commonly understood to be the correct organisation of a specific number of Notes etc, which should be played in a certain time [duration].

Takt… die ganze Taktnote [A specific note-value] … the whole-note [semibreve]

Takt … Taktart, z.B. dieses Tonstück steht in geraden Takte. [Metre]: Type of Tactus, e.g. this piece is in equal [duple] time.

Takt … Bewegung, z.B. dieser Satz hat sehr geschwinden Takt [Speed]: Movement, e.g. this composition has a very fast Tactus

Takt… von der äusern Abtheilung durch die Bewegung mit der Hand, z.B. den Takt schlagen. About the showing of division [i.e. beats within a bar] by moving the hand, e.g. beating time.

Der Takt ist das Maß der Bewegung eines musikalischen Satzes Tactus is the Measure of the movement of a musical composition.

Takt… ist das Zeitmaß der Musik, die Abmessung der Zeit und der Noten Tactus is the Measure of Time [duration] in music, the measuring of Time and of the notes.

Differences between 1592, 1789 & 2020

Barlines

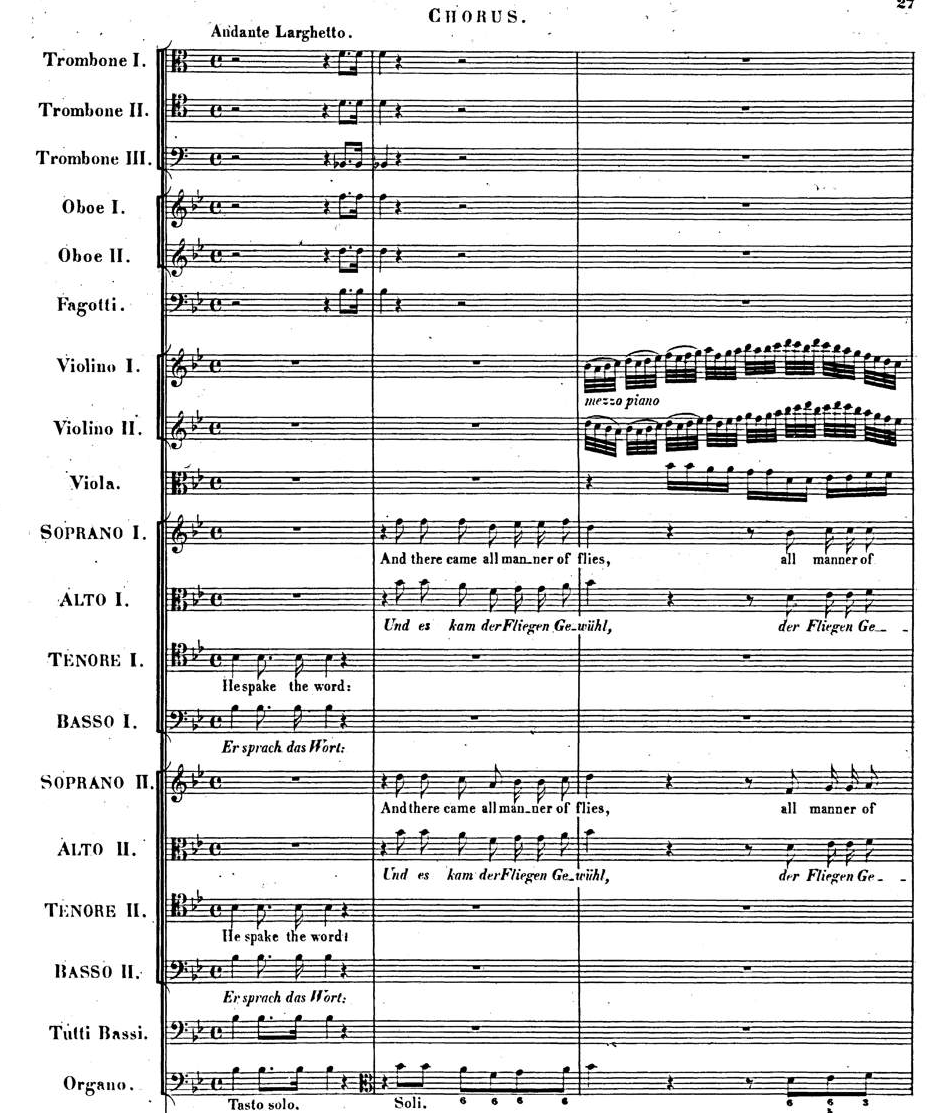

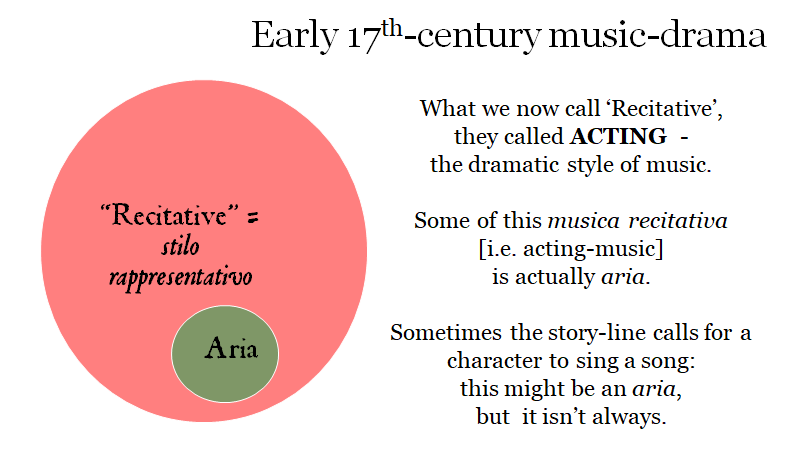

As we still do today, Türk associates Takt with notated bar-lines, which are not part of Zaconni’s practice. In the ‘new music’ of early seicento Italy, barlines are either absent, or irregular, and there is no association of bars with a fixed duration in notation or in real-time, and certainly no principle of ‘bar = bar’ for navigating proportional changes.

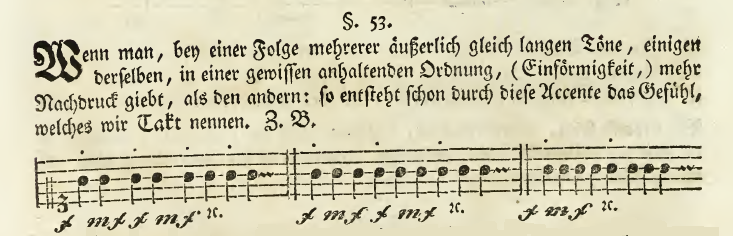

Accent

As we still do today, Türk associates Takt – in the sense of Metre – with accent. And so his first definition would have shocked Zacconi: Wenn man, bey einer Folge mehrerer äuserlich gleich langen Töne, einigen derselben, in einer gewissen anhaltenden Ordnung, (Einförmigkeit), mehr Nachdruck giebt, als den andern: so entsteht schon durch diese Accente das Gefühl, welches wir Takt nennen. When, in a succession of many apparently equally-long notes, you give some of them more emphasis in a certain consistent pattern (uniformity): then these Accents produce the feeling that we call Metre.

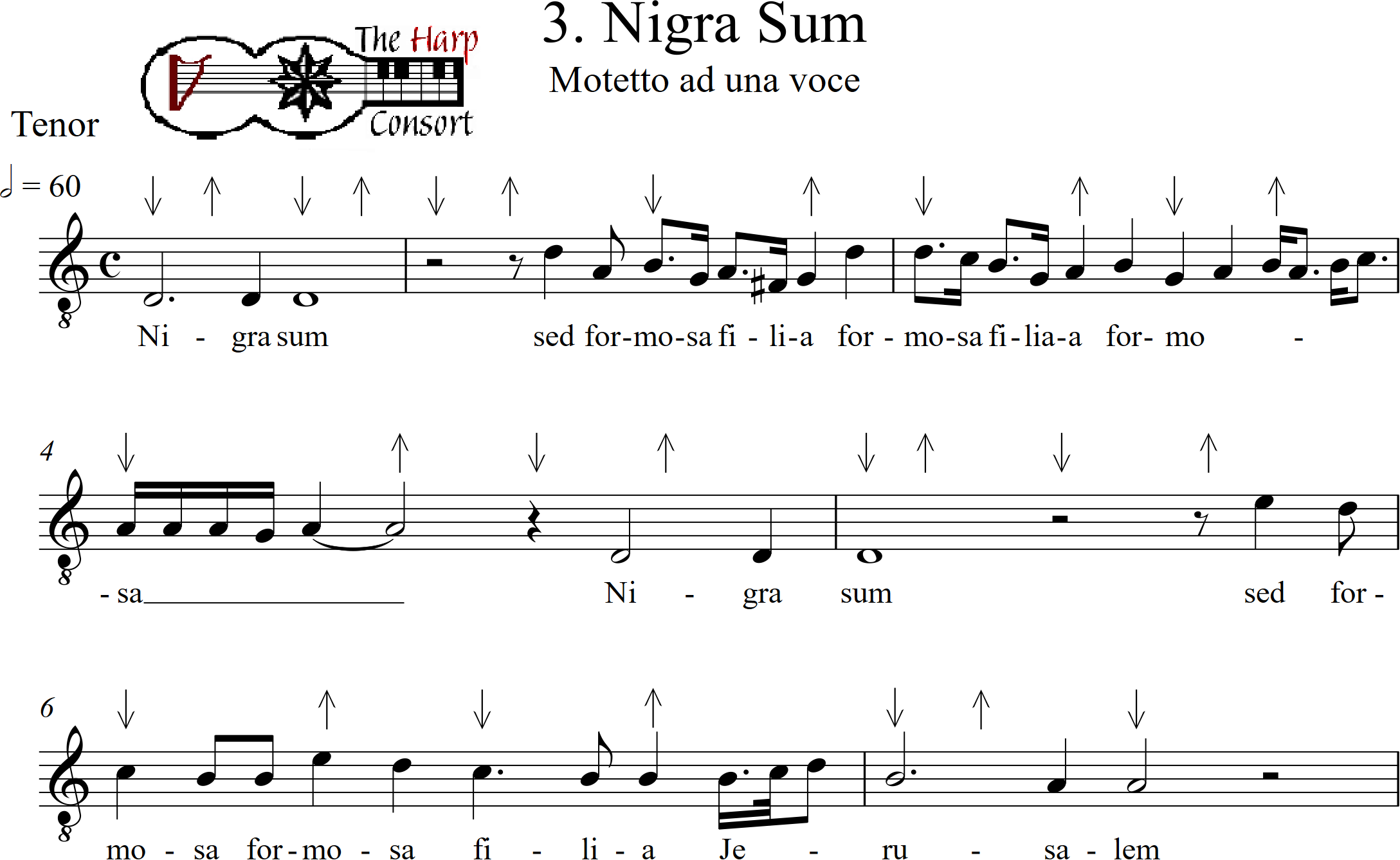

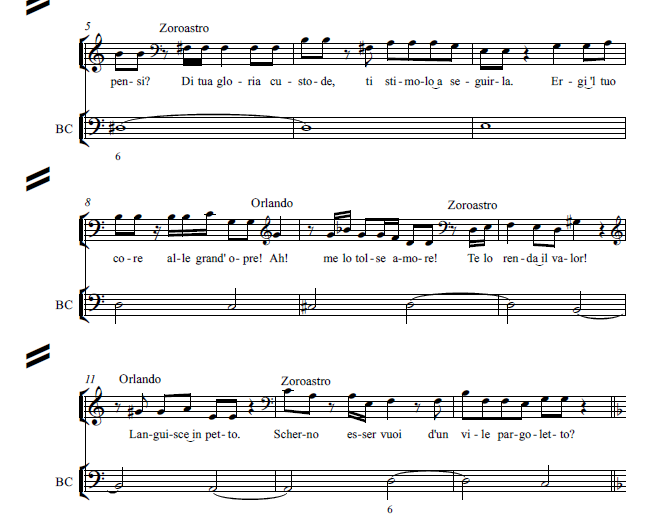

In sharp contrast, Zacconi discusses Tactus, Time, Measure, Beating Time, Beats and even Metre without any reference at all to accents. In old-fashioned polyphony and in the new music of the 1600s, although the accented syllable of a word often falls on the Tactus-beat, quite frequently it does not. Even if there are bar-lines, they too do not imply accentuation. Tactus is a feature of the measurement of Time, whereas accents are determined by words. Metre – as notated and shown by Tactus-beating – does not necessarily match the poetic scansion of the words, or the dance-rhythms suggested by harmonic changes.

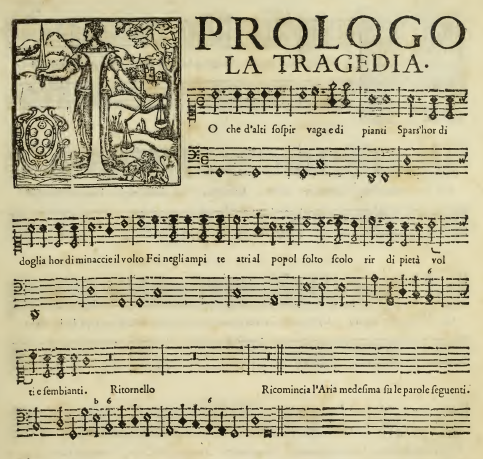

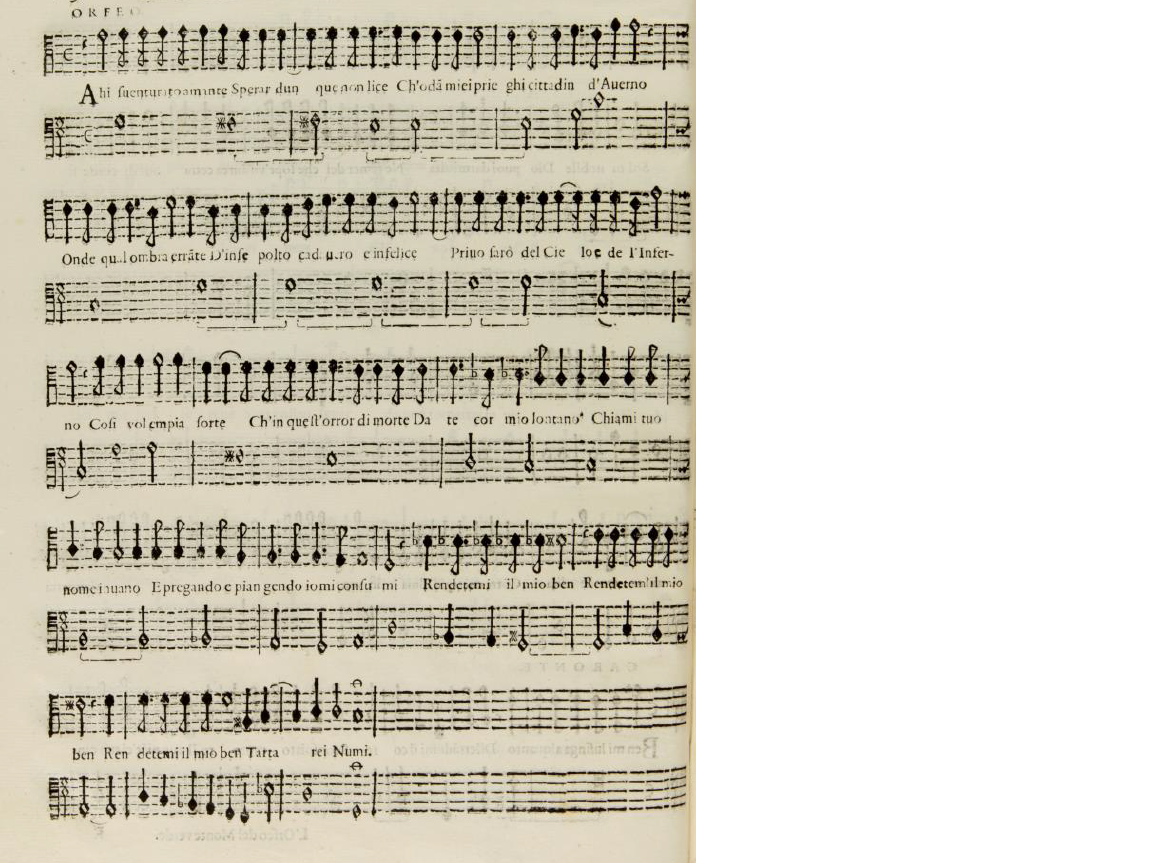

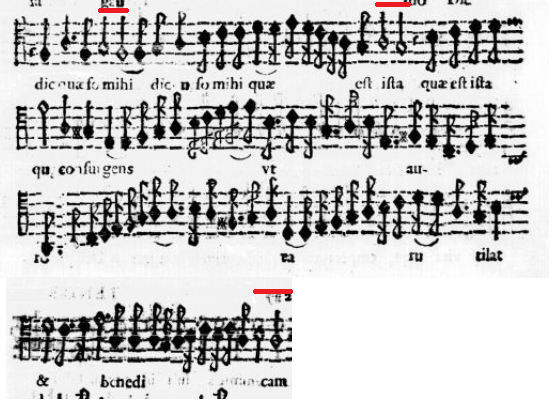

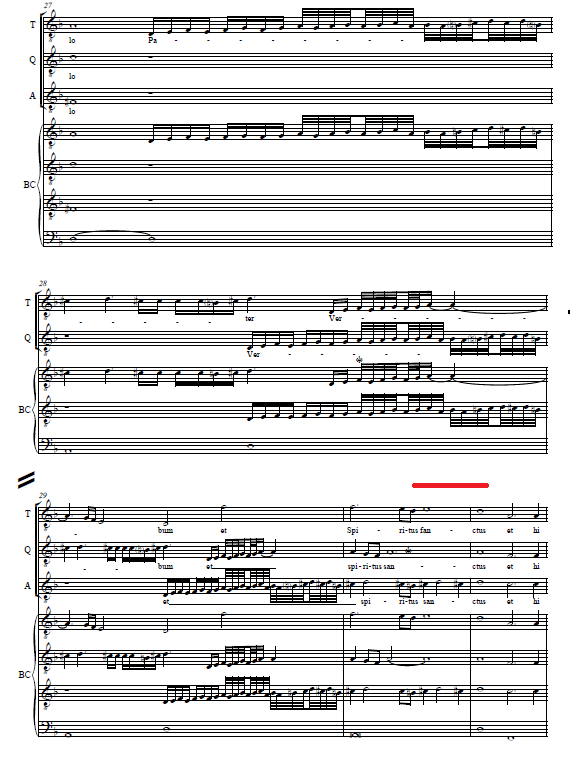

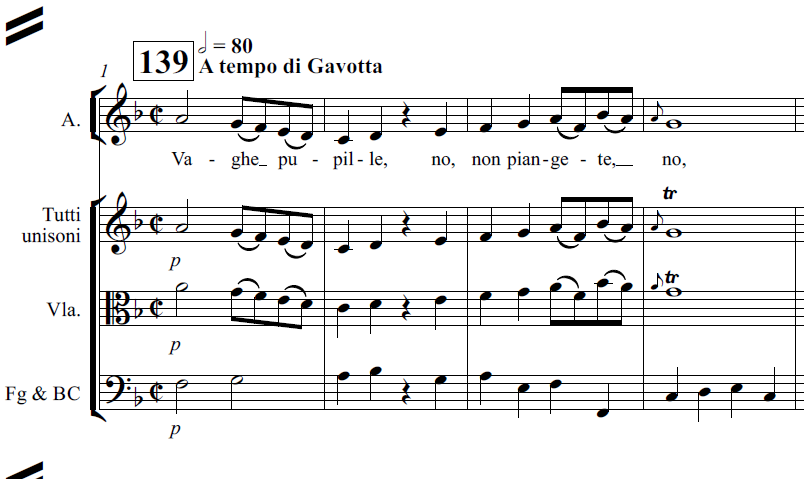

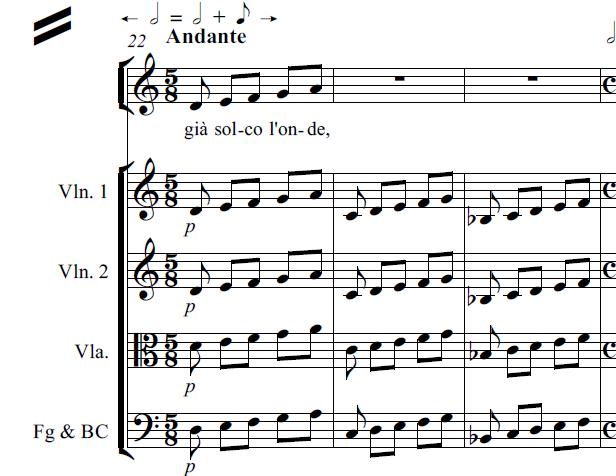

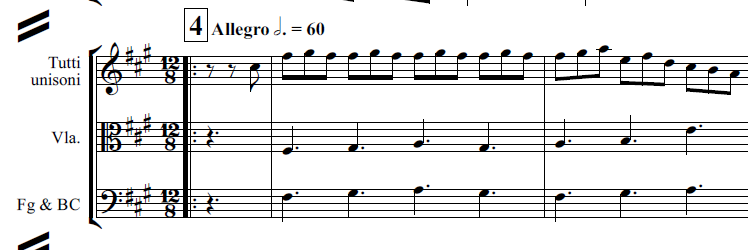

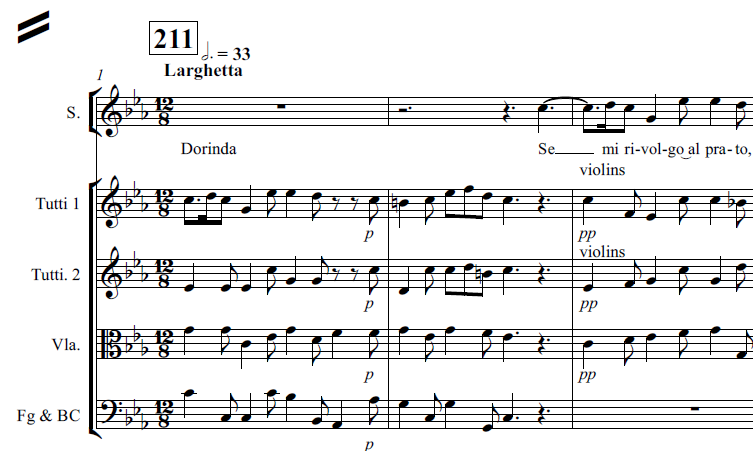

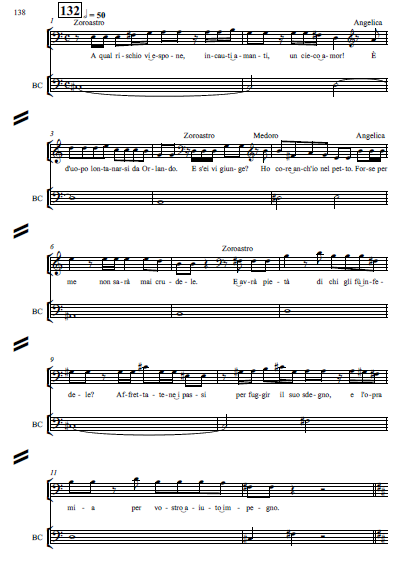

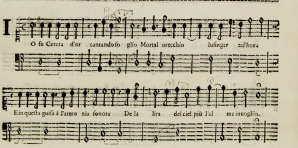

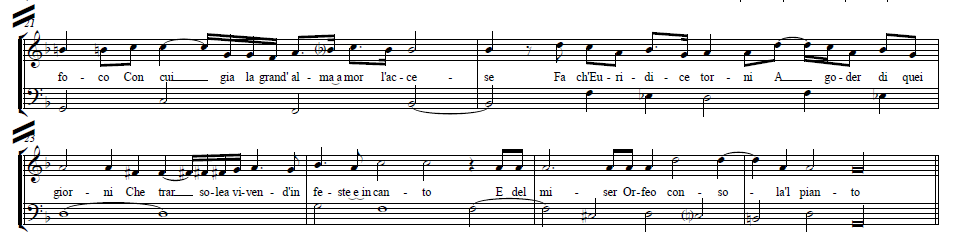

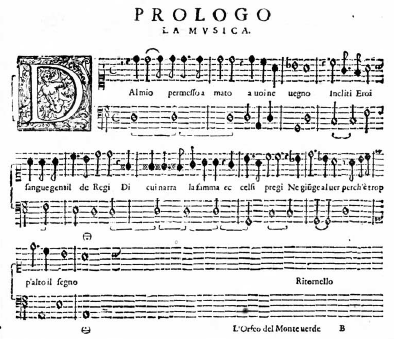

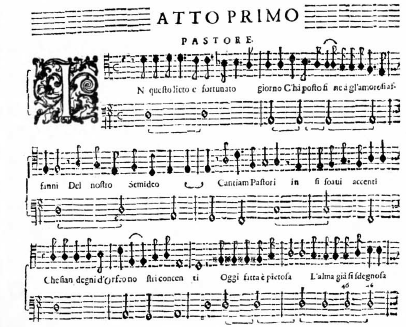

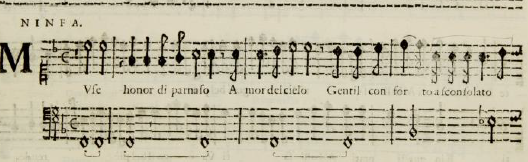

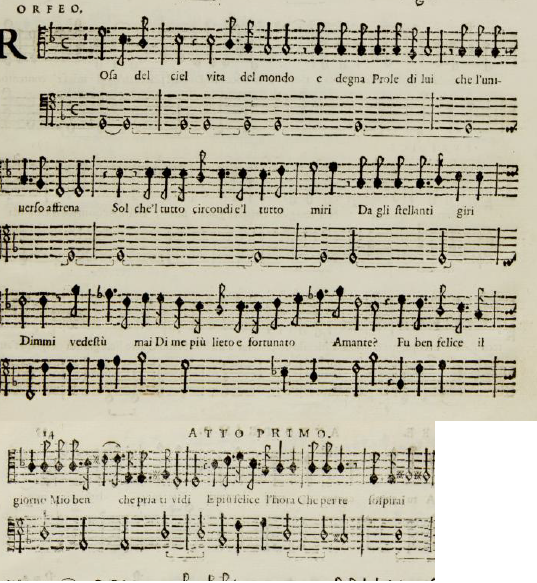

In this oft-cited excerpt from Monteverdi Orfeo, published in 1609, the mensuration mark of C indicates an equal (i.e. duple, down-up) Tactus beat on minims, something around minim = 60, and the barlines are every four minims. But the harmonic metre is clearly in groups of three minims [as shown by the red brackets] and the word-accents fall mostly (but not exclusively) on the first and third minims of these groups. Thus the notation of musical Time is not matched to the metrical structure of harmony and accents. This allows Monteverdi to notate a steady speed, with three minims corresponding to three one-second Tactus-beats to the metrical unit. Contrariwise, if he had used the triple-metre notation of his time, e.g. a tripla Proportion, this notation would direct the singer to fit the whole metrical unit into one Tactus-beat, three minims in one second of actual time: the music would be heard three times as fast.

Unfortunately, many modern editions rebar this song under a 3/2 time signature, which performers then interpret as if it were Monteverdi’s tripla porportion – we often hear this music much too fast!

And failure to understand the subtle relationship between Tactus and word-accent (sometimes coinciding, but not always) has led many singers to disregard Monteverdi’s precisely notated rhythms in so-called Recitative. See It’s Recitative, but not as we know it.

Re-discovering 17th-century, non-accentual, Time is a considerable challenge for modern-day performers. Well-intentioned 20th-century attempts to ‘escape the tyranny of the bar-line’ have led us to rhythmic Hell: the rejection of the stable self-government of Tactus, even to the anarchy of free rhythm. There is still much work to be done, in learning (not only in theory and practice, but as an instilled habit) how to manage stable, but non-accentual, Tactus-time, and how to weave complex patterns of word-accents (imitated also in instrumental music) around that Tactus. This learning cannot take place in an ensemble directed with modern conducting.

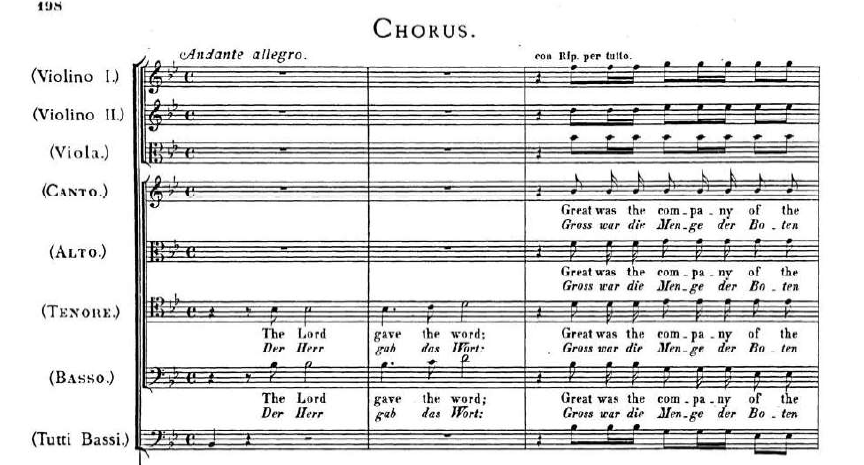

Speed

For both Zacconi and Türk, there is a closer and more specific relationship than for modern musicians between Tactus as sign, notation, duration in real time, a way of beating time, a specific note-value and sub-division of that note-value into various rhythms. Although both writers allow the possibility that the speed of Tactus-beating can vary somewhat, this variation (I would argue) was small: gross changes in the speed of the music (as heard) were acheived by changing the notation whilst the beat remained (more-or-less) constant.

After the slow song cited above, Monteverdi continues with the same Tactus and the same relationship between notated Time, indicated Tactus, and note-values as performed. But the sound changes noticeably, as singers, violins and continuo-bass suddenly move in bursts of quavers rather than semibreves & minims. It feels faster.

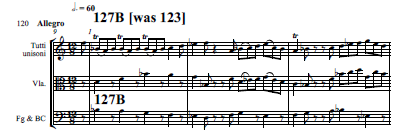

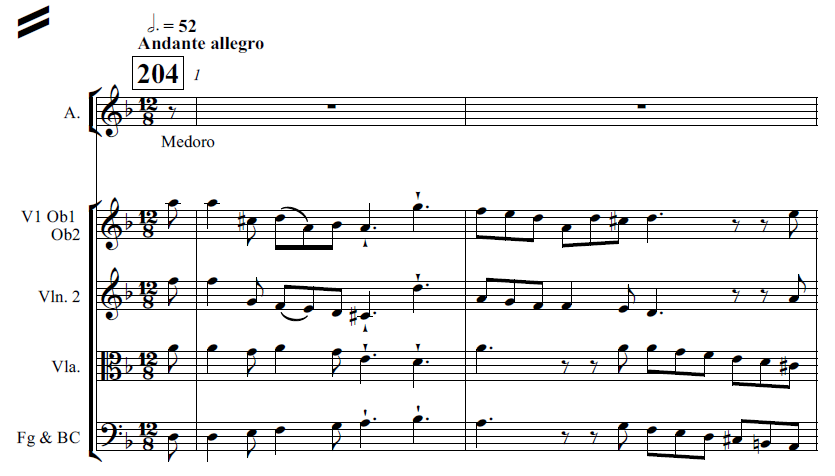

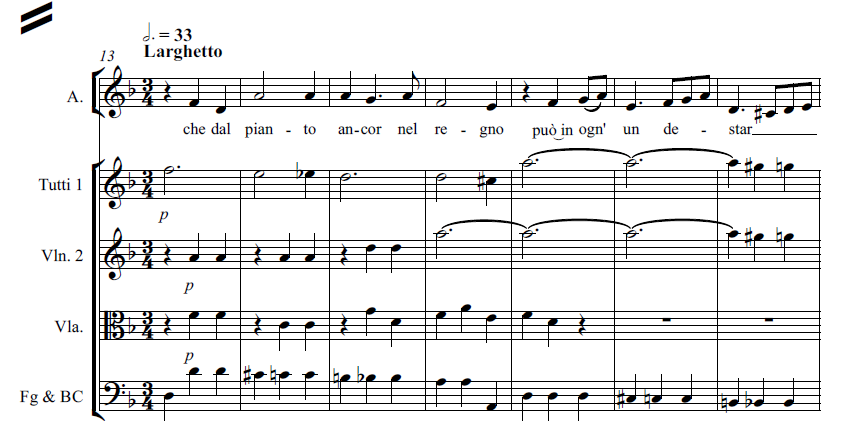

In the following Ritornello, the Tactus again continues unchanged. But the relationship between that Tactus and notated Time is altered by the sign of Proportion. The black minims now come three to the Tactus – the effect heard is that the music feels three times faster than the first song.

There is academic debate about the details of precisely how Proportions should be interpreted. But there is general agreement on the essential principle that the Tactus is maintained (or varied only subtly) whilst a proportionally greater amount of music happens within the real-time duration of that Tactus. See Tempus Putationis: getting back to Monteverdi’s Time. Proportions feel faster.

One of the challenges when studying the subjective feeling of Speed in baroque music is that Zacconi and his contemporaries did not share our concept of Newtonian Absolute Time. Within their Aristotelian understanding of Time as dependent on motion, the Tactus did more than indicate a musical beat, it created Time itself. That real-world time was related to notated durations by the signs of tempus and Proportions. We encounter not only differences in period nomenclature, but conceptual gaps in historic language, when we try to unpick ‘the feeling that we call Speed’ for baroque repertoire, just as Türk encountered a similar gap amongst established authorities when trying to define the emerging concept that ‘Accents produce the feeling that we call Metre’.

Addition or Division?

Türk’s statements on Takt seem to be ordered with the most up-to-date ideas first, established views next, and citations of older authorities (some which might even derive from Zacconi) in a footnote. Following his description of Takt as accentual metre, his next remark would have struck musicians of previous generations as fundamentally incomplete.

Jeder längern oder kürzern Note, Pause &c ihre bestimmte Dauer geben… so spiele man nach dem Takt. Giving longer or shorter notes, rests etc their proper duration… this is playing in Time.

Here is an early indication of what was to become the most significance difference in the management of time in practical music-making of the Baroque period from modern-day practices. From the first teaching-book (Milán’s 1536 El maestro, discussed here) and even in Türk’s following remarks, it is not sufficient that performers add up the durations of each individual note and rest… they must also ensure that the total duration of the note-values that add-up to a unit of notated time corresponds to the duration of real-world time, as shown by the Tactus.

Saber quantas de las sobredichas cifras entran en un compas (Milán, 1536) Know how many of the above-mentioned notes come in a Tactus [in notation, and in performance].

The essential control of period rhythm was not by adding-up small note-values, but by maintaining the relationship of notated Time to real-world Time through (and at the level of) the Tactus. As Roger Mathew Grant aptly expresses it in Beating Time and Measuring Music (2014), notation is “calibrated” to real-world Time by the Tactus. Smaller note-values were found by dividing the Tactus – a universal principle underlying the specific practice of ornamental ‘diminutions’ or ‘divisions’.

This is the concept of Tactus as the Measure of Time. In actual music-making, it’s the practice of using Tactus to measure Time. And it’s what most musicians do not do, nowadays.

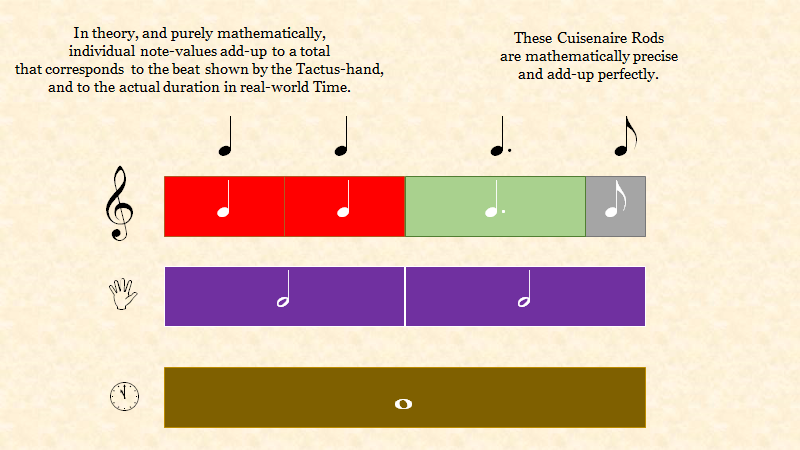

Tactus as Measure

In theory, and purely mathematically, it should make no difference whether one adds or divides – the rhythmic total is the same either way. But in practice, and with human performers, there are considerable differences in the resulting delivery and even greater differences in the subjective ‘feel’ of the music. I’ll try to illustrate this visually, by means of the Cuisenaire Rods used for learning mathematics from the mid-20th century onwards.

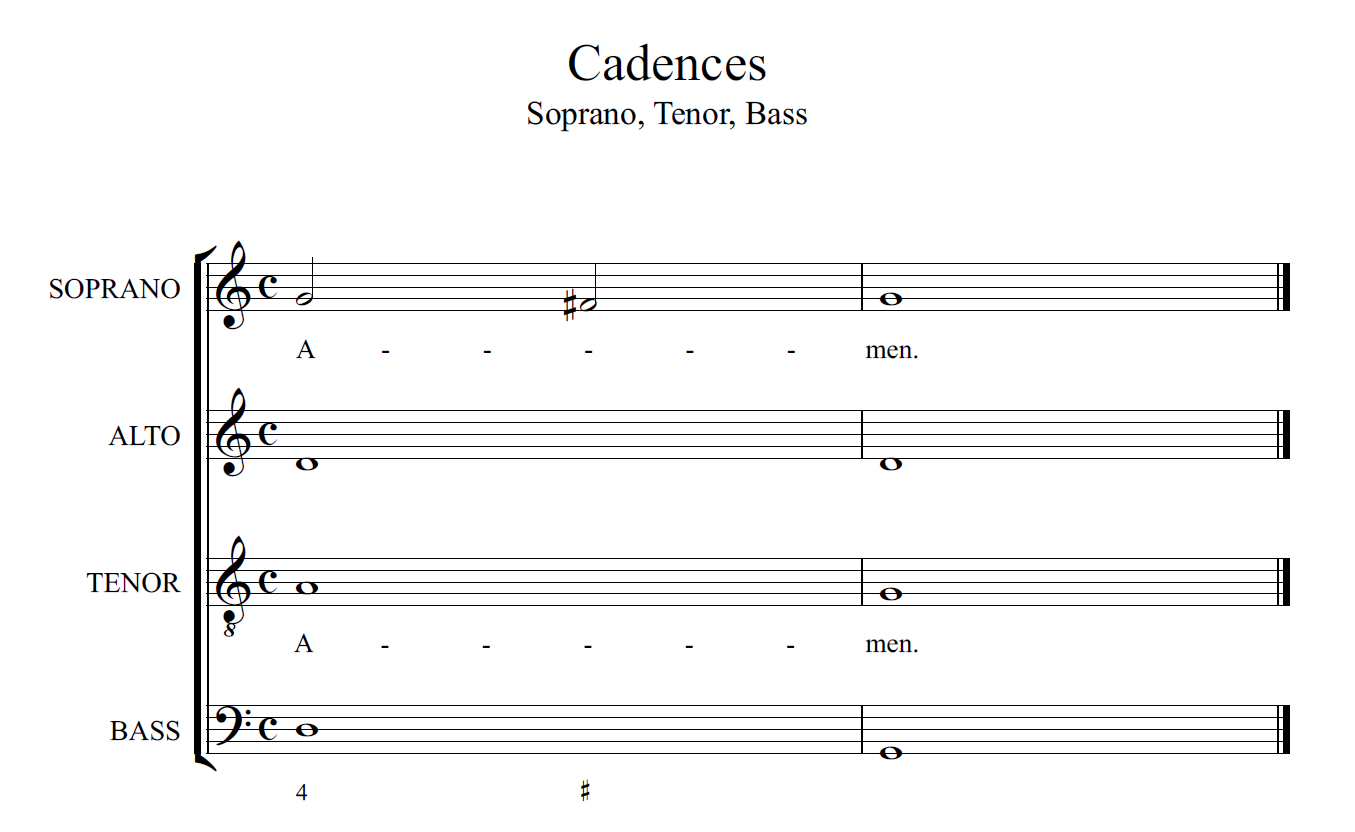

In theory, a performer (or conductor) counting with a short beat (e.g. 4 crotchets to the bar) and adding-up the various note-values should arrive at the same total duration as one counting with the long beat of Tactus (one minim down, one minim up).

In practice, small errors and/or deliberate choices accumulate so that modern counting/conducting and historical Tactus sound – and, even more importantly, feel – noticeably different.

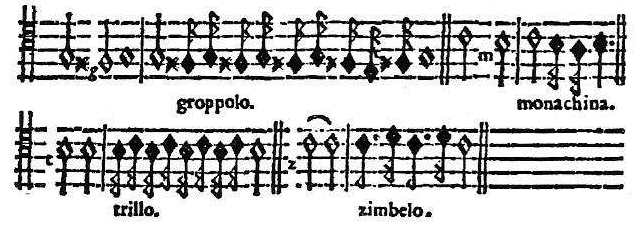

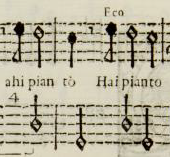

Ironically, amongst today’s Early Music perfomers, stylised articulations and ideas of ‘musical gesture’ etc often result in even greater disconnect from Tactus-Time. Many of those articulations are based on historical evidence and period principles: good/bad notes here , silences of articulation, over-dotting, etc. Caccini gives examples of how to sing typical phrases more gracefully: the common feature of all his examples is exaggerated contrast in note-values – long notes are lengthened, short notes are shortened.

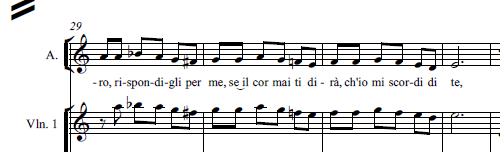

There is no denying the historicity of ‘non-mathematical’ rhythm – varied lengths for notes written as equal, extra contrast for dissimilar note-values, varied articulations between notes etc – but all these subtle adjustments should happen within the Tactus. The note-values affected are shorter than the Tactus, and the cumulative result is determined by lining-up with the next Tactus beat.

This is the essential difference between modern playing and Tactus-playing: whether or not musical Time is measured by Tactus. And the only way to do Tactus-playing is – to adopt Zacconi’s form of words – by actually doing the action! Unless you study initially and then practice regularly with actual physical Tactus (the down-up motion of hand or foot) then you are not using Tactus to measure your music-making. Unless you rehearse Proportional changes with a Tactus hand-beat, you are not managing Proportions according to Tactus.

In the hope that you would like to try it for yourself, here is the first part of my free online course on The Practice of Tactus.

Frescobaldi explains here that (physical) Tactus facilitates even those difficult (and carefully delimited) moments where the Tactus itself should change. And Monteverdi notates what may well have been a common feature of performance, that soloists may choose to sing elegantly off the beat, whilst the continuo accompaniment remains in Tactus, like a jazz-singer syncopating against the steady groove of the rhythm section. See Monteverdi, Caccini & Jazz.

The Tactus-beat is human, rather than metronomic. The down-up movement has the almost imperceptible ebb and flow of arsis & thesis (look very carefully at the Tactus-Cuisenaire rods in my last example). And the Speed of the movement, which in principle is always the same, changes subtly in practice according to performance venue, ensemble forces, emotional state etc. It does not have to be precisely the same, from one occasion to another [for all this, see Zacconi, above], but you should keep it steady, as much as humanly possible.

Ideally, we do not force the Tactus to be faster, in order to mimick emotional agitation; rather we feel the emotional effect of the words, and even though we think we are keeping the same Tactus, actually we are going faster. Tai Chi master Sifu Phu expresses this idea – what actors call ‘working from the inside outwards’: Feel the Force, don’t force the feel! See also the discussion of the psychology and physiology of the Four Humours in Joseph Roach’s (1985) survey of the historical Science of Acting: The Player’s Passion.

It should feel as if the Tactus is always the same, but since we are human, it will not actually be the same, if we were to measure it objectively with modern equipment. Nevertheless, this subjective feeling of, and striving for perfect steadiness and consistent speed is utterly different from the arbitrary choices and changes of modern conducting. In this sense, Zacconi’s description (Chapter 33) of how the Tactus feels is both what performers should strive for, and what we hope our audiences will perceive.

Tactus is regular, solid, stable, firm… clear, sure, fearless, and without any perturbation.

Il Tatto… deve essere si equale, saldo, stabile e fermo… chiaro, sicuro, senza paura & senza veruna titubatione, pigliando l’essempio dell’attione del polso o dal moto che fa il tempo dell’Orologgio… following the example of the pulse [heart-beat] or clockwork.

When we have come to appreciate the effect of measuring our music-making with Tactus, and remembering Zacconi’s identification of tatto [Tactus] with tempo [real-world time, and the notation of tempus], the full force of his comment that Tempo is ‘soul of music’ becomes apparent. The element that ‘gives life to music’ is not just rhythm in general, but the interconnected working of notation, physical time-beating, real-world time and musical performance, all co-ordinated at the heart-beat level of approximately a minim per second, and (like a heart-beat) rocking to-and-fro in what we feel to be subtly uneven pairs.

This is not only the sound of Baroque music, it is the shape of Baroque Time.

(ALK, 2020)

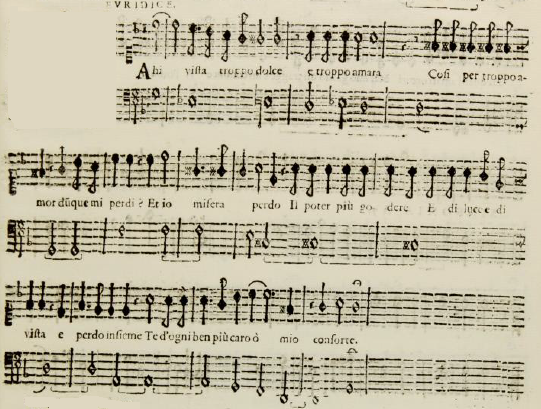

Senza misura

There are fascinating repertoires in baroque music that are written with specific note-values, but carry performance instructions for senza misura. Caccini specifies this (once only!) in his example song in Le Nuove Musiche (1601), here. But there are many pieces from the mid-17th century by Froberger that are marked to be played with discrétion, and some of these have the additional instruction in some sources sans observer aucune mesure [without observing any Measure]. See Schulenberg on Discretion here, and on Froberger sources here.

There is plenty of academic discussion of the challenge that Froberger and his copyists faced in trying to notate his highly idiosyncratic performance style. But for today’s performers, rather than taking discrétion as an invitation to introduce 20th-century tempo rubato, a possible approach based on period evidence could be to apply all that we know about articulation, rhythmic adjustments (following Caccini and Monteverdi), good/bad notes, dissonance/resolution etc etc, but without any obligation to make all this add up to the Measure of Tactus.

One might almost suggest that since the standard practice of much of present-day Early Music is to play without observing Tactus, that Caccini’s senza misura and Froberger’s discrétion are heard in almost every performance of every baroque repertoire, robbing [sic] audiences of the emotional impact of what should be a special effect, by soul-destroying [sic] over-exposure.

Conclusion

Zacconi’s concept of Time as the Soul of Music is much more than a trite platitude to remind us that rhythm matters. Rather, he expresses a fundamental element of Baroque practice, that music (and even the ‘affections of the Soul’ i.e. affetti, emotions) are created by a life-giving three-in-one of notated tempus, physical Tactus-beating, and real-world Time, operating (in early-seicento Italy) at the level of a semibreve ~ down/up ~ approximately two seconds.

Today’s Early Music performers mostly fail even to try this: instead we argue about pitch, temperament and vibrato. “Doh!“ (Dan Castellaneta as Homer Simpson, 1988 – but I use the Oxford English Dictionary spelling from 2001) See Music expresses Emotions?

I give the last word to Türk, who proclaims his continuity with centuries of music-making measured by Tactus, by his translation (explicit) and updating (implicit, since his Takt – however similar – is no longer exactly the same as Zacconi’s tempo and tatto) of that period mantra, as his own last word on the subject. Der Takt ist … die Seele der Musik.

Tactus is the Soul of Music