Havendo considerato le nostre passioni, od’ affettioni, del animo…

Monteverdi begins the Preface to his Eighth Book, Madrigals of Love & War (1638), by considering Passions (or Affections) of the Spirit – in modern parlance, Emotions. And one of the most emotionally moving pieces in the collection is the Lamento della Ninfa, in which the Nymph’s Lament is framed and accompanied by male-voice trios, accompanied by continuo. This article examines Monteverdi’s performance instructions for the Lament, revewing the original printed parts with an updated understanding of the historical performance practice context.

Lamento della Ninfa BC

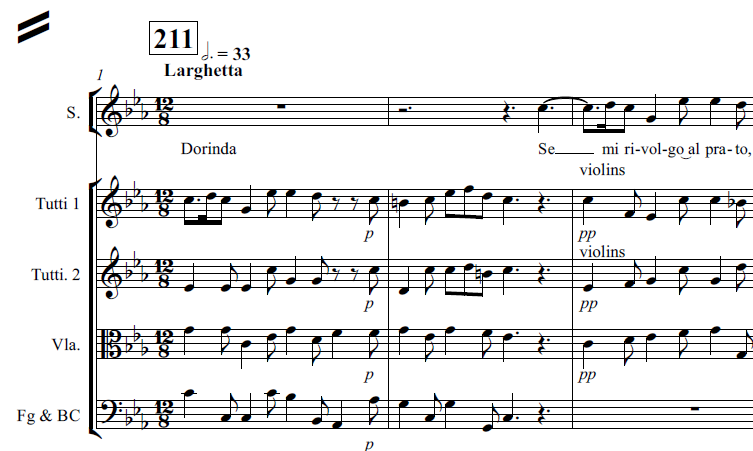

The original publication is in part-books, with the Preface printed in each book. The “framing” trios set the scene initially, and offer a commentary, in the manner of a Greek chorus, afterwards.

Non havea Febo ancora

“Phoebus [the sun] had not yet brought day to the world, when a young girl went out from her own dwelling. In her delicately pale face could be seen her sadness. Often there came bursting out a great sigh from her heart. Treading on flowers, she wandered here and there, crying for her lost love as she went.”

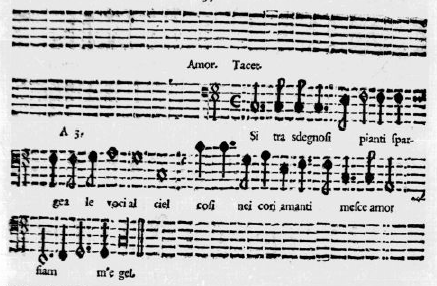

Si tra sdegnosi pianti

“Thus with angry cries she cast her voice to heaven. Like this, in the hearts of lovers, Amor [Cupid] mixes flames and ice.”

Amor, Amor dicea

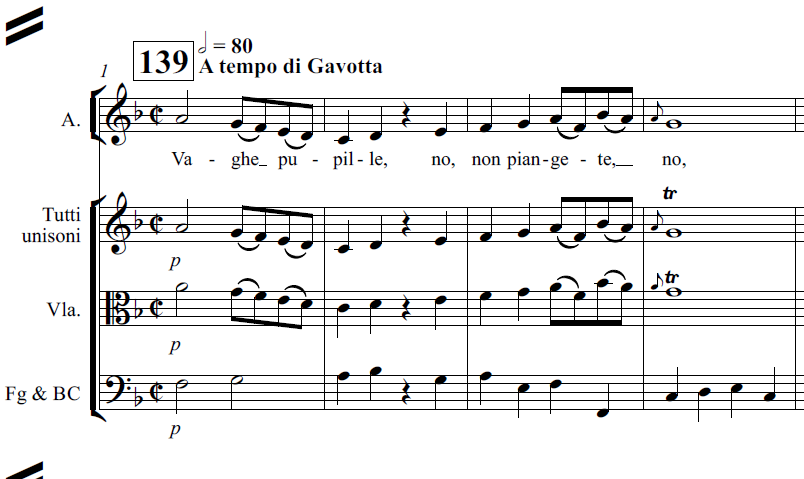

This central section is the Lament itself, set for solo soprano over a four-note descending ground bass, with the accompanying trio both narrating – “she said” “looking at heaven, her footsteps stopped” and commenting “poor girl”, “no, no!”, “so much ice cannot be suffered”. Monteverdi distinguishes this section (but not the framing trios) as rappresentativo ‘in show style’ or ‘acted out’.

This distinction is anticipated on the title page, which promises:

Madrigali guerrieri, et amorosi con alcuni opuscoli in genere rappresentativo, che saranno per brevi episodi fra i canti senza gesto

“Warlike and amorous madrigals, with some small works in show style, which will make short episodes amidst the songs without action.”

Whilst singers would use at least some hand gestures in any performance context, madrigals were normally sung as chamber music, i.e. the (occasionally gesturing) performers did not attempt to embody a role, they were not ‘representing’ a character in a dramatic scene. In contrast, the ‘staged’ pieces, including the Combattimento di Tancredi & Clorinda also found in this book, were intended as a dramatic surprise during a courtly soiree of madrigals and instrumental music. These elements of contrast, surprise and drama are missing when the Lamento is performed as a conventional concert-piece.

The distinctive nature of theatrical music calls for particular elements of historical performance practice, and Monteverdi provides specific information for the central, dramatised Amor section, distinct from the framing trios. In this article, that oft-quoted advice is re-assessed, considering other information from the part-books, and in the context of an improved understanding of Monteverdi’s assumptions about rhythm.

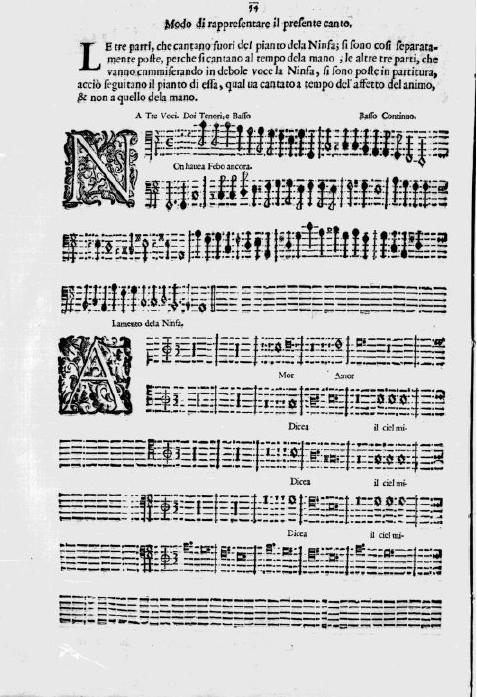

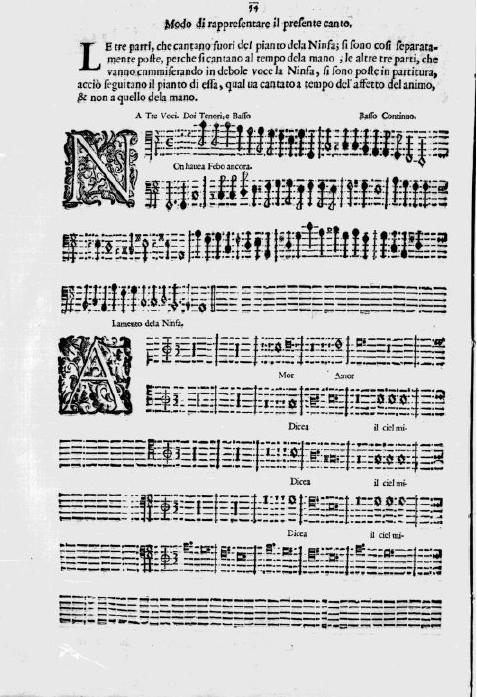

How to stage this song

The three parts that sing outside the cries of the Nymph are placed separately like this, because they sing in the time of the hand; the other three parts, which go in soft voice commiserating the Nymph are placed in score, in order to follow the crying of that girl, which is sung in the time of the affection of the spirit, and not in that of the hand.

Clearly, Monteverdi is putting into practice the consideration of the ‘passions of the spirit’, of emotions, mentioned in his Preface. But how are his instructions to be realised in performance? In the 20th century, the answer seemed self-evident: this is ‘expressive’ music, and ‘expressive’ performance suggests rhythmic freedom, tempo rubato. In this view, the framing trios would be sung in strict time (tempo della mano) whilst the central Lamento would be sung in free rhythm (tempo del’affetto del animo) and not in strict time (non a quello della mano). Performers found this rather counter-intuitive: triple metre and the regular bass of the central Lamento seemed more suited to structured rhythm, and 20th-century habits resisted strict time and a steady tempo for the framing trios.

Another 20th-century misunderstanding should be quickly mentioned: ‘the three parts’ which ‘are placed separately’ means that the three individual voice-parts and continuo accompaniment were placed in four different part-books, whereas the central Lament is printed in score. There is no suggestion that the three singers should be ‘placed separately’, i.e occupy another area of the stage, at some great distance from the solo Nymph!

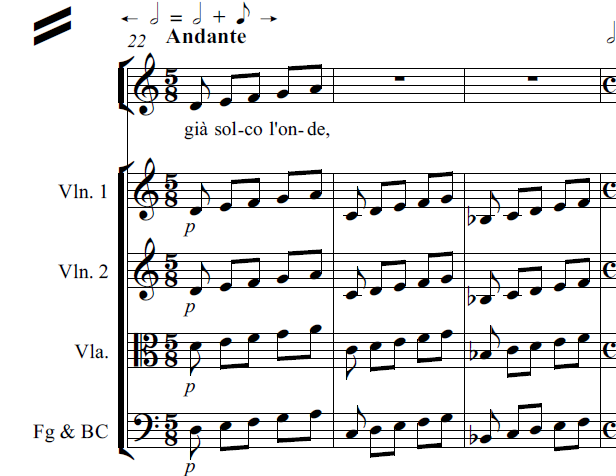

As Monteverdi writes, the arrangement of the individual parts and score can be seen in the part-books: it is ‘like this’:

Non havea Febo ancora T1

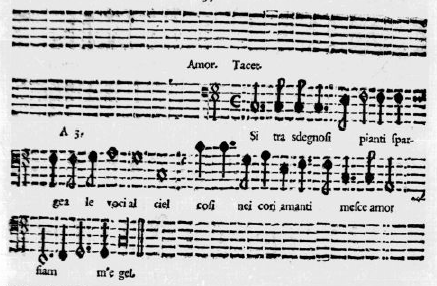

Si tra sdegnosi pianti T1

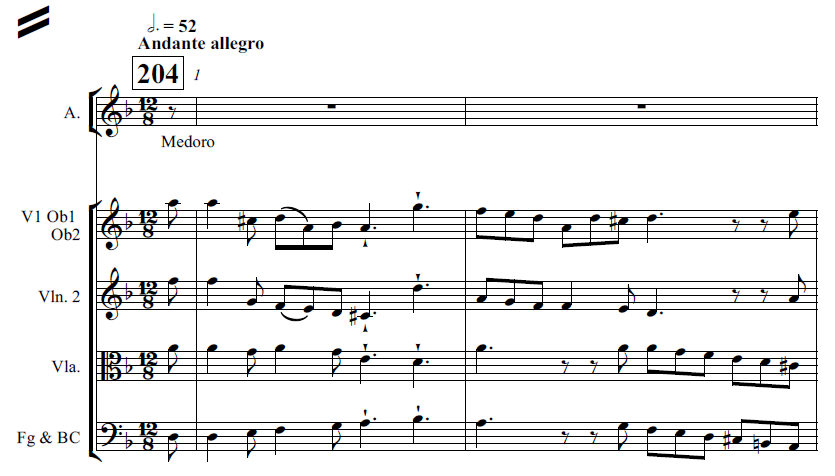

The framing trios are separated into individual voice-parts, in three different part-books: Tenore Primo, Tenore Secondo, Basso Primo.

The three parts for the accompanying trio are in vocal score, in another part-book, Alto Primo. This score shows the continuo bass only at the beginning, otherwise STTB.

Lamento vocal score in A1

The Canto Primo part-book has the soprano solo, in short score, soprano & continuo bass. The trio parts are not included in this short score.

Lamento short score in C1

The Continuo part-book has the instructions, and the music is printed as promised: bass-line only (with very few figures) for the framing trios; a full score for the Lamento. This score has STTB & BC throughout (no figures). [See above]

If one wished to perform the piece from a set of part books, two or three continuo-players could read from the one book. The accompanying trio could all three read from the Alto Primo book. (The name Alto Primo does not imply that an alto voice-type is required: instrumental and vocal parts for particular pieces are routinely placed in whichever part-book has space, and is not otherwise in use). The framing trio would read from three individual books T1 T2 B1. And the soprano soloist would read from the Canto Primo book.

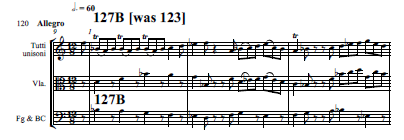

The arrangement of the material strongly suggests that there are six male singers, i.e. two trios: one trio for the framing sections, a different trio for the central Lament. True, it’s not impossible for the framing singers to put aside their individual part-books at the end of the intro, cluster around the score in the Alto Primo book for the Lament proper, and then pick up their individual books again for the coda. But there is additional evidence in the part-books supporting the six-men option. In the individual part-books for the framing trios, the central Lament is mentioned, with the indication tacet.

Amor – Tacet in B1

Similarly, before and after the vocal score, the framing trios are mentioned with the indication tacet. The index pages of the partbooks are consistent with this.

Tavola (index) in T1

And Monteverdi’s instructions specify ‘three parts’ and ‘the other three parts’. All of this is consistent with the six-men version, and inconsistent with a three-man performance.

It is interesting to consider whether the soprano and accompanying trio might have memorised their parts: this would be effective in the ‘staged’ section of the piece, and would remove some of the practical difficulties of three-man performance. But the markings of tacet remain a stumbling block: if the three men were supposed to switch part-books (at least in rehearsal), one would have hoped for an indication that this should be done, and of where to find the required score.

There is also the question of how much rehearsal time was available. Monteverdi’s letters include several pleas to try a new piece through at least once, before performance (even for very complex music): this does not give the impression that there would be sufficient rehearsal time to memorise parts without additional effort. A decade or so earlier, a ‘little priest’, the male soprano hired to act the role of Euridice in Orfeo (1607) had great difficulty learning ‘so many notes’: as an experienced singer of religious polyphony, his difficulty was not ‘note-learning’ per se, but memorisation. However, the skills of court chamber-music singers might have changed with the introduction of professional singing-actors into ‘baroque opera’, beginning with La Florinda’s triumph in Arianna (1608).

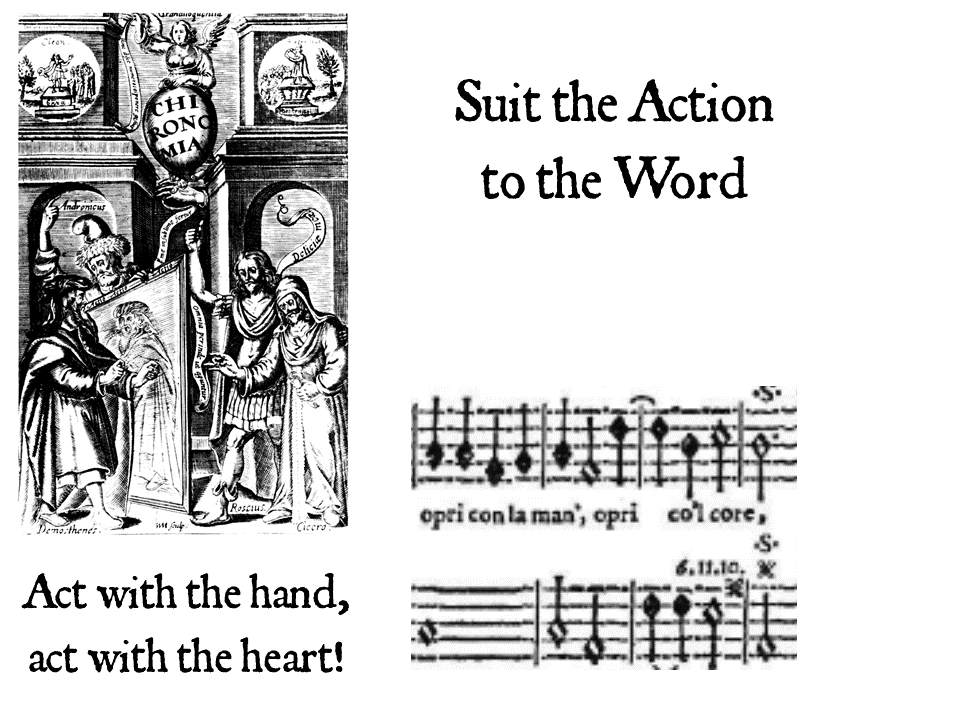

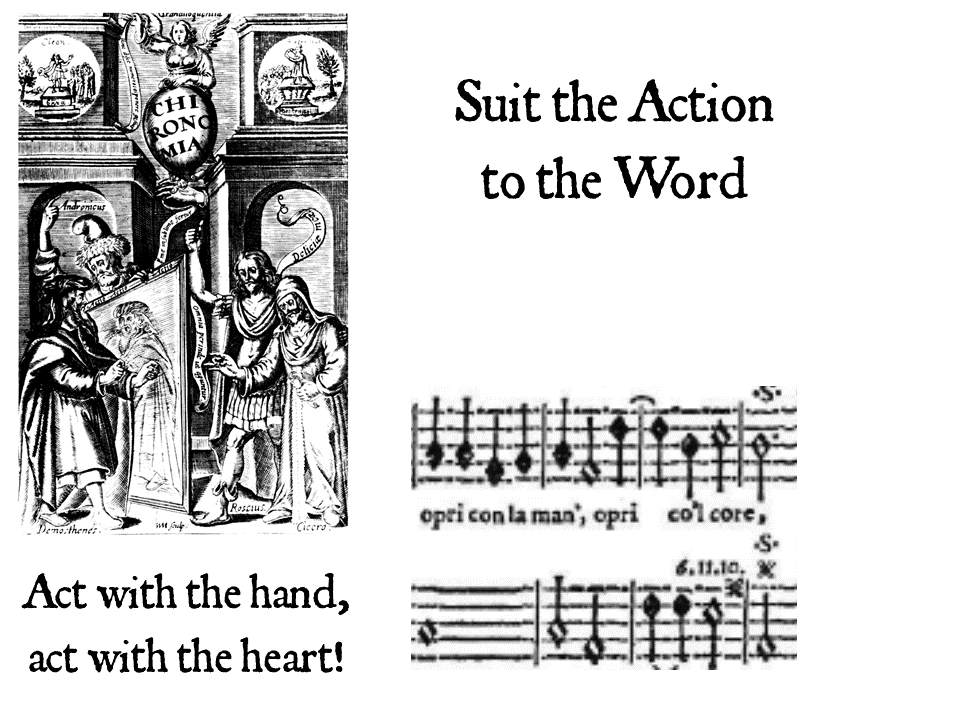

Hand & Heart

Act with the hand, act with the heart!

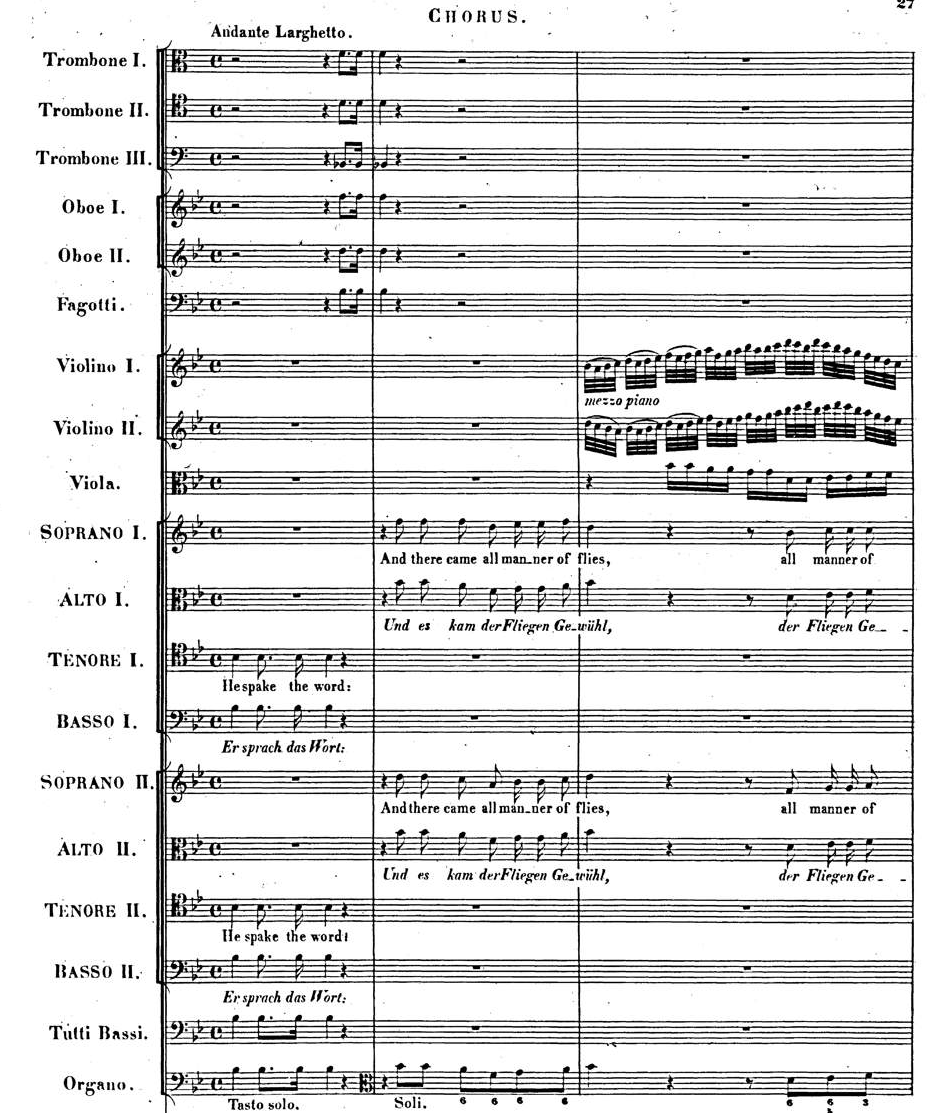

The interplay between music, gesture and emotions is frequently mentioned in period discussions of music-drama, i.e. what we nowadays call ‘early opera’. Although Monteverdi’s instructions for the Lamento contrast ’emotional time’ and ‘hand time’, the preface and libretto of Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima e Corpo (1600) here as well as many other sources connect emotional impulses with visible action. The designation rappresentativo implied a particular set of performance practices, coordinating text, music and action into a unified spectacle. Here are Monteverdi’s instructions for Combattimento, in the warlike part of Book VIII.

“Combat of Trancredi & Clorinda in Music, described by Tasso, which needs to be done in show style: they enter suddenly (after some madrigals without action have been sung)…. They make their steps and gestures just as the delivery of the text expounds, neither more nor less, observing carefully the tempi, sword-strikes and foot-work; the instrumentalists [observe carefully] the violent and soft sounds; and the Narrator [observes] the well-timed pronunciation of the words – in such a way that the three actions come to meet in a unified representation. ”

“The ‘three actions’ to be ‘unified’ are the protagonists’ movements, the music, and the narrator’s text. When Clorinda or Tancredi speak, the Narrator is silent. The voice of the Narrator should be clear, firm and well pronounced… so that it is better understood. He should not make divisions [literally ‘throat’, i.e. fast-moving ornamental passage-work] or trills except in the Aria that begins Notte, all the rest should be given a delivery similar to the passions of the oratory. ”

The instruction to avoid ornamentation (both divisions and graces) is found in many sources, including Cavalieri’s Preface to Anima & Corpo. Many sources also require the continuo to avoid ornamentation and play grave – low register and slow notes. Cavalieri also emphasises the importance of whole-body acting, not just hand gestures. Monteverdi asks for a variety of tone-colours from the instruments, Cavalieri makes a similar request to the singers.

The silencing of the Narrator, when there is direct speech from characters onstage, suggests that the six-man version of the Lamento might better distinguish between narration and direct speech, by keeping the narrating trio silent whilst the commiserating trio are heard within the staged scene.

Monteverdi’s call to unify text, music and action reminds us of Shakespeare’s instructions to the players in Hamlet:

Suit the action to the word, the word to the action.

And Shakespeare’s admonition against ‘mouthing’ the speech, like a town-cryer, is consistent with Cavalieri’s warning to singers not to force the voice.

Monteverdi’s Preface makes a similar link between theatrical music, spoken oratory, and emotions:

Tasso, come poeta che esprime con ogni proprieta e naturalezza con la sua oratione quelle passioni, che tende a voler descrivere

“Tasso, as a poet… expresses with all propriety and naturalness in his oratory the passions which he wants to describe.” The connection between detailed description and emotional power is the period concept of Enargeia. Read more about Enargeia here Enargeia VIP.

Meanwhile, many early 17th-century sources compare the new style of singing to speaking (Caccini 1601, here) , to the pitch-contours of spoken delivery (Peri 1600, here) , and to the variety of tone adopted by a fine actor in the spoken Theatre (the anonymous c1638 guide for a music-theatre director, Il Corago here).

Suiting the stage action to the words of the libretto implies that the sung text can serve almost as Stage Directions for the actors. The Nymph should enter at the same moment as the narrating trio sing una donzella…. usci. Her face should be made up to look pale, and she should sigh heavily as she treads on flowers, wandering erractically across the stage. She might make a hand gesture for dolor.

As she begins to sing, her footseps halt and she looks up at heaven. This is consistent with Gagliano’s instructions in the Preface to Dafne (1608) for singers to enter making an interesting path across the stage, but to stand still whilst singing. In another Monteverdi madrigal the love-sick protagonist similarly addresses heaven: Sfogava con le stelle (Book IV, 1603).

Il Tempo della mano

Such close agreement between many period sources encourages us to attempt to reconcile Monteverdi’s remarks about tempo in the Lament with all that we now know about early 17th-century time and rhythm. The word tempo has many historical meanings: Time itself, musical rhythm, the psychological effect of perceived musical rhythm. This last meaning comes close to our modern usage of tempo to mean the speed of musical performance, measured in beats per minute. There is also another area of period meaning linked to the Greek distinction between chronos (chronological time) and kairos (the moment of opportunity). For sword-fighters, a tempo is the opportune moment to strike. This meaning is relevant in theatrical music as ‘dramatic timing’ and might be particularly significant in Monteverdi’s instructions for Combattimento (above).

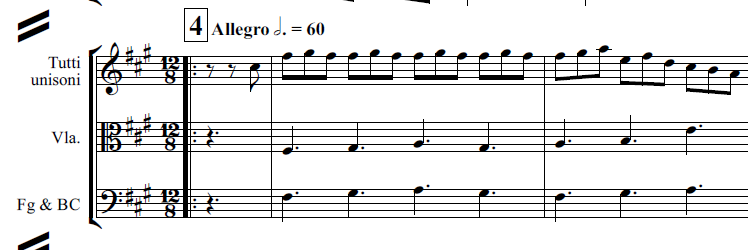

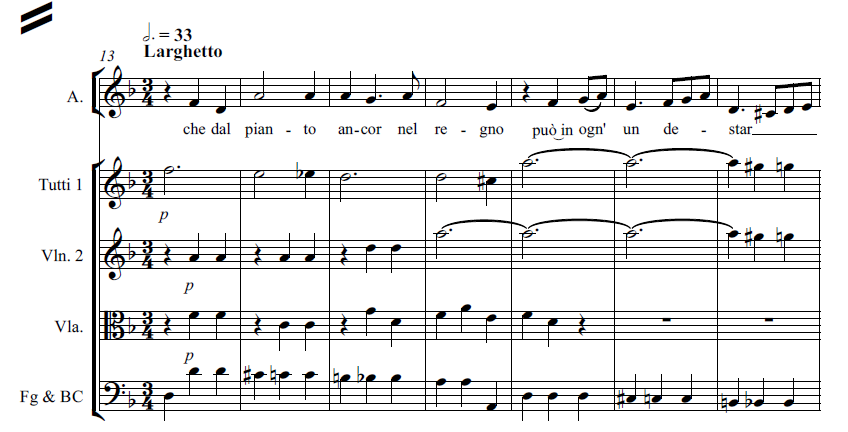

Monteverdi died in same the year (1643) that Isaac Newton was born. So the composer’s concept of Time was not the Newtonian model of Absolute Time so familiar to us today, but rather Aristotle’s understanding of Time as dependent on motion. Monteverdi’s musical rhythms were organised by the slow, steady pulse of Tactus (about one beat per second), with triple metre measured by simple ratios – Proportions. The notation of the Lamento indicates Sesquilatera (one and a half) Proportion, with three triple-metre semibreves in the time of two duple-metre minims, something around semibreve = MM90. Read more about Getting back to Monteverdi’s Time.

In practice, Tactus was shown by a simple down-up movement of the hand. Tactus-beating was usually done by a performer, not by a stand-alone conductor, and was very different from modern conducting. The job was not to make one’s own personal choice of tempo, nor to interpret the music by changing the tempo, but to find and maintain the correct tempo. According to Zacconi’s Prattica di Musica (1592),

Tactus is regular, solid, stable, firm… clear, sure, fearless and without any perturbation

Quite unlike modern conducting!

Of course, most instruments are played with two hands, so musicians would study using a Tactus hand-beat, in order to play with an internalised sense of Tactus. Frescobaldi confirms this, by discussing keyboard toccatas entirely in terms of Tactus. Even though he specifies certain situations where the Tactus may change between movements of a single piece, and even though keyboard players cannot physically beat Tactus whilst playing, Frescobaldi insists that the performance is still facilitated by, actioned by, Tactus. And he links his Tactus Rules also to ‘modern madrigals’, the kind of music found in Monteverdi’s later books. Frescobaldi rules, OK: here.

Applying Frescobaldi’s rules, we might try a small change of speed where the ‘movement’ changes, i.e. between the frame and central Lament, perhaps even within the introduction (a pause after dolor and a slightly faster speed for the new rhythmic structure of si calpestando fiori; slower again for cosi piangendo va). Such small changes follow the changing emotions of the text, and therefore would tend to exaggerate the composer’s change of note-values. The notation of si calpestando fiori already responds to the text with short note-values, any change in Tactus would increase the contrast. But within what Frescobaldi calls a passo (literally step or movement: i.e. a self-contained section or movement of a single work), the Tactus remains “regular, solid, stable, firm… clear, sure and fearless”. Frescobaldi limits ‘any perturbation’ to very specific situations.

For theatrical music, Il Corago discusses the question of whether or not the omni-present Tactus should be shown with hand-beating. Obviously, the singing-actor cannot beat time on stage, and Il Corago considers that the continual waving of a Tactus-hand at the side of the stage would be distracting for the spectators, taking away the sense of naturalezza that Monteverdi so admired in Tasso’s poetry-reading. So he recommends that the principal continuo-player should beat Tactus where required in ensemble music, but there should be no time-beating in dramatic solos. We might therefore expect the leader of the continuo to give a couple of Tactus-beats to start the framing trios, but that there would be no Tactus-beating during the central Lament. Of course, the Tactus is still maintained during the Lament solo, “regular, solid, stable… clear, sure, fearless”, but felt, rather than seen.

This advice from Il Corago is consistent with Monteverdi’s marking for another acted-out soprano solo, the Lettera Amorosa in Book VII (1619) Se i languidi miei sguardi, which has the instruction:

in genere rappresentativo e si canta senza battuta

“In dramatic style, and to be sung without beating time.”

It is also consistent with Agazzari’s advice that the continuo (his word is fondamento, emphasising the structural, rather than decorative role of bass-playing) ‘supports and directs the whole ensemble’. The directing is done not by beating time, but in the manner of playing, by providing clear structural rhythm in the improvised realisation of the accompaniment. This contrasts with 20th-century assumptions and practices, in which the continuo is supposed to follow, whilst the singer (perhaps a conductor too) destabilise the rhythm with rubato.

The early-17th-century assumption is clear from Peri: singers are normally guided by the continuo. If the text is sad or serious, the singing should not ‘dance’ to the rhythm of the bass, so the bass itself is reduced to Tactus values of minims and semibreves. This guiding role of the continuo affects not only the rhythm but also the emotions, so Peri is careful to compose the entire bass-part according to the words. Agazzari agrees: ‘true and good music’ doesn’t require lots of fugues and imitative polyphony, but rather the imitation of the emotion and similitude of the words, affetto e somiglianza delle parole.

This seems very close to Monteverdi’s a similitudine delle passioni del’oratione in his instructions for Combattimento (above). Even instruments are expected to imitate words – especially the Basso Continuo (according to the Preface to Book VIII):

Le maniere di sonare devono essere di tre sorti, oratorie, Armonicha & Rithmicha

“There are three elements of playing: oratory, harmony and rhythm.” What an inspiring definition of continuo!

But in his discussion – also in the Preface to Book VIII – of repeated semiquavers in the bass-line of Combattimento, Monteverdi’s assumption is tha the continuo-realisation would normally reduce such fast notes to structural values of minim or semibreve, were it not for his specific instructions to play what is written in this particular piece. This is consistent with Landi’s notation of two bass-lines in the sinfonias of Sant’ Alessio (1631), a complex line for harps, lutes, theorboes & bowed strings, and a simplified, structural line for continuo harpsichords.

So the continuo maintained the Tactus, even whilst responding to the emotions of the text. Nevertheless, there was a seicento practice of rhythmic freedom for singers, which Caccini describes as senza misura (unmeasured). Many examples in Monteverdi’s works show how this works: the singer anticipates the beat, or arrives late, but the continuo maintain Tactus – “regular, solid, stable, firm… clear, sure, fearless and without any perturbation”. This baroque practice is similar to jazz, where the singer floats freely over a steady Iin the rhythm section. It remained in use throughout the 18th century (clearly described by Leopold Mozart) and even later. In Chopin’s style of playing ‘timeless melody over a timed bass’, he kept the bass as steady as the trunk of a tree, whilst the melody can sway like the leaves and branches. Chopin here.

Senza misura over a Tactus bass – Caccini

Soloist floating around a Tactus bass – Monteverdi

Solo tenor and Tactus – Monteverdi

In this context, we can understand Monteverdi’s intention that the framing trios would be directed by a hand-beat in Tactus, il tempo della mano, whereas no-one would beat time during the acted-out Lamento. But we would still expect the Lamento to be sung in (unseen) Tactus. The “regular, solid, stable, firm” Tactus of the Lamento movement might be a little different from that of the framing trio. The text of the coda summarises the Lament as ‘angry cries’ sdegnosi pianti which might suggest a faster, more passionate tempo, rather than slowing down for a Romantic ideal of lamenting. Baroque laments – includingly the famous Lamento di Arianna (1608) and Act V of Orfeo (1607) – often alternate sadness with anger.

The Four Humours – changes of ‘humour’ move the passions

Il Tempo dell’affetto del animo

But what was Monteverdi’s ‘time of the affection of the spirit’, his ’emotional tempo’, and why did it require the singers to read from a score? The 20th-century assumption was Romantic rubato. But nowadays, we know that if the singer floats freely around the (unseen) beat, the continuo would maintain the Tactus groove ‘without any perturbation’.

There are several instances in the (1610) Vespers where the rhythms for the singers differ between the individual part-books and the continuo-book short score. This is not problematic, because the continuo-players did not follow such small details of ornamentation; rather they led with the slow steady pulse of Tactus. Continuo-players were accustomed to singers’ improvising diminutions and graces, and would not follow these or be upset by them: they would just continue in Tactus “regular, solid, stable, firm… fearless”.

So if the lamenting Nymph employed some rhythmic freedom, in the manner described by Caccini and notated by Monteverdi, there would be no unfamiliar demands on the continuo players, or on other members of the vocal ensemble, and no special need for a score. Indeed, continuo-players were accustomed to scores that showed different ornamentation from what the soloist was actually singing!

Perhaps the answer can be found not in the anachronism of Romantic rubato, but in that wonderfully practical source for historical music-theatre, Il Corago. The anonymous writer explains precisely how continuo-players did ‘follow’ the singing-actor in staged performance. If some extra time was needed for some stage ‘business’, the continuo should just repeat the chord they are playing. We see this notated in Monteverdi’s Ulisse (1640) and described in Cavalieri’s Anima & Corpo.

Si replica tante volte

Monteverdi Ulisse: “This Sinfonia (a C minor chord for the basso continuo, played twice, long-short) is repeated as many times as necessary, until Penelope arrives on stage and starts to sing.”

Cavalier Anima & Corpo: “The instruments that have to accompany the singers wait, playing the first chord, until he [the actor in the role of Tempo] begins.”

In this performance practice of historical music-theatre, a stage-wait is managed by having the continuo repeat a chord, in Tactus. Although everything waits until the actor is ready, the Tactus-clock is still ticking. So we can reconcile instructions that continuo-players should follow actors in staged works with the overwhelming weight of evidence that Tactus was “regular, solid, stable, firm ” in all seicento music. Indeed, the period term is musica mensurata, measured music, which applied to all music, except unmeasured liturgical chant.

So even if the Nymph felt she had to wait for the passion of her spirit to motivate her speech, the tempo of her emotions would be measured by Tactus, even if it was not shown by a hand-beat.

But it is not plausible that the continuo players would repeat one of their four chords indefinitely, whenever the soprano decided to wait! Again, Il Corago suggests a practical solution: if the continuo know how long they should wait, they can play a little chord sequence. instead of just repeating one chord. In the context of the Lamento’s ground-bass, it’s obvious that the continuo would just repeat the four-note descending ground, as many times as necessary, until the singer started, or (in the middle of the piece) re-started.

Now we understand why scores are necessary. The soprano needs a short score, so that if she waits, she can make her entry at the correct point in the repeating harmonic sequence. (She only needs her part and the bass, since the trio will follow her). The accompanying trio need a vocal score, so that they can be aware if the soprano waits, and make their entries according to her part. (They don’t need the ground bass, since they coordinate their entries with the soprano).

Seicento singers were accustomed to managing misprinted rests in polyphonic music: their familiarity with the style and their general musicianship skills allowed them to sense the right moment to make their entry, in order to fit with the general harmonic movement around them. But in the Lamento, these skills would be no help in dealing with the extra time imposed by an emotionally inspired soprano: the trio polyphony would work on any given iteration of the ground bass. The trio singers needed a score to know whether they should wait four bars, or eight bars, extra: their ears alone could not solve this problem.

In the end, this kind of performance would not sound very shocking to us today. So the continuo put in a few extra rounds of the ground bass, here and there? Probably quite a few modern performances have already done this. But this is easy for us to do, because we are accustomed to reading from scores, and (all too often!) being conducted. If there are only part-books, no conductor, but regular Tactus, it would be difficult for a soprano to wait spontaneously, according to the emotions, without the trio getting lost: without a score, much rehearsal would be needed before the soprano could safely be given this freedom. Monteverdi’s solution was practical, but unusual for his period: give the singers a score!

What does remain shocking for today’s performers is the idea of keeping Tactus; that singers might float around the beat, but the continuo will maintain the groove; the idea that even large-scale music was led by continuo-playing, not by conducting. What is the point of providing early instruments and historically informed performers, only to have them anachronistically conducted. We might as well realise the continuo on a 20th-century pianoforte!

To sum up: baroque music is measured by Tactus and directed by continuo-playing. But a soloist has freedom to float around the steady groove of that Tactus. In staged performance, additional time can be taken for dramatic action, but the ticking clock of Tactus continues. In this Lamento (a staged piece written over a ground bass), the continuo could repeat the ground as many times as necessary, until the singer is emotionally ready to sing.

Monteverdi’s tempo dell’affetto dell’animo is not some kind of ‘free rhythm’, but rather an emotionally-driven sense of dramatic timing, to a steady heart-beat.

If your pulse stops, the music also dies [ALK]