This is the last in a series of articles following up classes on Early Music on Modern Harps that I taught this semester for the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, London. Although our case-studies come from harp repertoire, the principles we explored are relevant for any Historically Informed performer. This article could make a useful introduction for any modern instrumentalist or singer.

Previous articles in the series discuss Historical Principles & Online Resources, Principles & Practice, Ornamentation and Dance Music. Our focus was on the 18th century (specific works by J. S. Bach, Handel, C.P.E. Bach, Mozart) and the principal sources consulted were the three Versuch publications around the middle of the century (Quantz, CPE Bach, Leopold Mozart), the Essai for harp by Meyer, and (back in 1698) Muffat’s remarks on French dance-style in Florilegium Secundum. Links to all of these sources and more, in the previous posts.

The questions below were asked by students in the final class, and/or arose from work-in-progress recordings of their baroque pieces that they sent me for private comments. Whereas in previous articles, the agenda was set by the historical priorities of period sources, in this post the questions were posed by today’s students. This is a significant distinction: what we today think is a high priority may not have been so important back then. It’s always good to assess from historical sources how significant your question was, in the dialetic of the period.

What are Good & Bad notes, are they just loud & soft?

The concept of Good/Bad notes is fundamental to renaissance and baroque music, and is given a lot of attention in historical sources. The underlying principle is that instrumental music imitates the human voice, playing as if the music had a text. In vocal music, the sung text is of paramount importance. Caccini (1601) writes that Music is “text & rhythm, with sound last of all. And not the other way around”. The structure of each mid-18th-century Versuch is a short introduction to musical fundamentals, followed by a large section on what Early Musicians call “articulation”: how to start a note, how to join or separate notes into short groups. For flute, this articulation is done with tonguing syllables; string instruments do it with bow-strokes; keyboard and harp do it with fingering patterns. This is a high priority question for period writers. See Principles & Practice.

Good & Bad Syllables

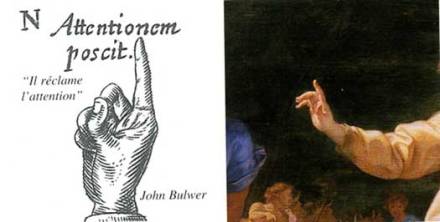

Good/Bad notes in music correspond to Good/Bad syllables in speech. In music and in poetics, these syllables are sometimes called Long/Short: Good is Long, Bad is Short. In modern terms, we would say accented and unaccented syllables. In the mediterranean languages, the accented syllable is not hit suddenly on the intial consonant, but gets its accent from a sustained weight on the vowel: this corresponds to Leopold Mozart’s description of a slow start to the bow-stroke, even on a loud note.

Thus, baroque violin teachers will often coach modern string-players to use a slow bow-stroke where an “accent” is needed. Similarly on the low-tension strings of early harps, a Good note can have a slow finger-movement. This is not so easy to apply to modern harp, where the heavy strings need a certain amount of snap in the finger-action. But imagining that the note has a slow bloom, rather than a percussive attack is already very helpful.

Comparing Good/Bad to language gives us the clue that it does not have to be exaggerated: it just has to be the right way around. When we say the word “around”, we do not make a large, or conscious accent on the second syllable. But we would notice immediately if someone accented the first syllable instead. This is what is needed for our Good/Bad notes too.

Good & Bad Beats

During the 18th century, the idea developed of an intrinsic heirarchy of the bar. Today, we learn this in our elementary music education. In common time, beat 1 is strong, beat 2 is weak. Beat 3 is medium-strong, but less than beat 1. Beat 4 is weak, or could be energised as an upbeat. This is the basic shape of Time, although particular pieces will make artistic variations around this underlying structure. The principle extends to sub-divisions of the beats: ONE + two + THREE + four + And to the next level of subdivision: ONE a + a two a + a THREE a + a four a + a. In 3/4 time: ONE a + a two a + a THREE a + a.

Good/Bad is definitely not forte/piano. But there is something of Long/Short about it, in two inter-related ways: how long is the note, and how long is the time-space it can occupy.

If we think about the repeated quavers in the Left Hand of CPE Bach’s Sonata, we could beat Tactus as quaver-down, quaver-up. These gives a pair-wise groove of Good-Bad. Time itself has this groove, so that ONE is imperceptibly longer than +. This intrinsic hierarchy of the bar gradually becomes the main focus of 18th-century discussions of Good/Bad, for example in Marpurg (1755).

Good & Bad Notes

Meanwhile, the notes we play into this grooved Time have a patterning of their own, the ONE is definitely a long note and the + is a short note. This relationship between notes was the focus of 17th-century discussion of Good/Bad, for example in Muffat (1698).

These two effects combine so that ONE is a long note fully occupying a long space; whilst + is a short note only partially occupying what is anyway a shorter space.

Quantz gives two ways of counting a slow 3/4, in quavers or in crotchets. If we count in crotchets, the groove is ONE two THREE, or Long Passive Short. So the downbeat quaver is a long note in the longest space; beat two has a long passivity; beat three is a long note in a short, actively upbeat space. All the offbeat quavers are short/bad. We could pronounce as a mantra something like the words “PLAYer, Silence, BEATer” to get the feeling of the combination of pairwise quavers with triple-metre crotchets.

And we need to practise the Left Hand, with any continuo realisation we might add, until this fundamental rhythm is absolutely correct.

Whilst it’s easy to grasp the intellectual idea of Good/Bad, it needs lots of practice to acheive it effortlessly and without exaggeration. That practice is training the ears to listen for Good/Bad and to spot any wrong-way-around relationships; and training the fingers to execute the phrasing as if automatically, and at a very subtle level. Ears and fingers must be trained in partnership.

A particular case of Good/Bad, and similarly linked to the scansion of poetry, is the idea that the last Good note in a phrase has the Principal Accent. Usually, this is not the very last note of the phrase, one or more Bad notes follow. A useful general rule therefore, is that for almost every phrase, the Last note is short and un-accented.

How to create ‘mini-phrases’?

In Baroque music, long passages of semiquavers are not ‘moto perpetuo‘, but are built-up from many short phrases. CPE Bach calls these Figuren (figures) the most short-term units (say 3 to 5 notes), and Gedanken (thoughts, ideas), perhaps linking two or three Figuren. One passage of semiquavers may contain several Gedanken, each containing several Figuren. Just as in Rhetorical Speech, we need to join together what belongs together, and separate each group of notes from the next group. These words occur very frequently in the Versuch, this is an important concept in this period.

Typically, this joining and separating creates rhythmic patterns that are maintained until there is a clear change. But from one unit to the next, even whilst the basic pattern is maintained (i.e. the same number of notes starting with the same relation to the Tactus, on-beat, after the beat, or before the beat) the sequence often continues by contrasts. A legato group is followed by an arpeggio group, a staccato group etc. See Principles & Practice.

Useful guide-lines are: “Last note short“, “Breathe after the one“, “Stepwise motion ~ legato, jumps ~ staccato“. A jump can also show the place for a mini-break. The mini-phrases are defined by mini-breaks, often between two successive semiquavers: the Tactus beat in crotchets or minims continues without faltering.

If the notes are not whizzing by too quickly, it may be possible to shorten the last note of a mini-phrase by damping, create an actual silence, and start the next mini-phrase with the appropriate Bad or Good articulation.

In allegro semiquavers, there will not be time for this. But the separation between one mini-phrase and the next can be communicated with an unaccented last note of the old phrase, a sliver of time for a mini-breath (but without disturbing the Tactus), an energised re-start of the new phrase, and a clear sense of repeating a unit, and of any contrast between the previous unit and the new one.

What about historical fingering?

This is another crucial concept for this period. After a short introduction, CPE Bach’s Versuch devotes almost a third of the book, pages 15-50, to fingering.

For harps and keyboards, 18th-century fingerings often clarify join/separate: the principle is to move the hand only in the mini-breaks, and keep each mini-phrase ‘in the hand’. This principle is utterly different from the modern concept of fingering, which seeks to make a passage as safe and efficient as possible. On the contrary, historical fingerings introduce deliberate ‘inefficiencies’, in order to discourage smooth joining of what is supposed to be separate.

In the following examples of harp-fingerings, I apply the principles of historical fingerings (from Meyer 1763 – see Online Resources – and – specially recommended, and now available free online – Cousineau 1784) to examples from CPE Bach’s harp Sonata and Mozart’s flute & harp Concerto.

[My Cousineau link takes you to the second ‘imperial’ edition, c1803. The Fuzeau facsimile publication states 1784 for the first edition, the US Library of Congress (who have online images of each page) says ‘1786?’ The title pages are undated. At the time of writing, an original second edition was being sold for €1,000]

An efficient modern fingering for CPE Bach second movement facilitates joining the third note D to the next G, with a hand-movement before the B [as shown by the square brackets].

EXAMPLE 1 CPE Bach

The guideline “breathe after the one” would suggest a separation after the D, making three upbeats to the middle of the bar. This is supported by the Figur in the LH, which has three upbeats at the end of the bar. So my historically informed fingering moves the hand “after the one”.

EXAMPLE 2 CPE Bach/Cousineau

In red, I show the Abzug (phrase-off, forte/piano, see below) in the Appoggiatura, recommended by many sources. CPE himself says that it is the most important element. Quantz gives detailed dynamic contrasts for each note within ornaments. Leopold Mozart instructs violinists to hineinschleifen (sneak into, slide into) the main note (piano).

After the second appoggiatura, we should also observe the good/bad relationship of F#-G, especially because the ornamented F# is the Principal Accent of the phrase, after which the guideline applies: “last note short, no accent”.

For a scale, Meyer gives two alternative fingerings. If there is nothing else afterwards, the standard fingering jumps the thumb to make the long note different from the run of short notes. Notice that within the scale, the hand jumps “after the one”. This is his default fingering. The alternative, more familiar to modern eyes, can be applied when the notes are very fast, but it lacks the detailed phrasing of the default option.

EXAMPLE 3 after Meyer & Cousineau

But the alternative becomes preferable, if the top note is not to be distinguished as ‘different’, but joined into the scale, with a break “after the one”. See Example 4.

In this passage from the first movement of the Mozart, the first note of the scale (treble C) is on the beat, so it is a Good. The next note D is also a good. For flautists (after Quantz): “Di diddle”, for – old fashioned – violinists (after Muffat): Down, down-up. (Leopold Mozart would probably apply some interesting slurred bowing). For harp, perhaps 4 4321321 encouraging a separation after the first note; rather than the ‘more efficient’ 4 3214321, which would join irrevocably after the first note.

EXAMPLE 4 Mozart

I have adjusted the beaming. The fingering follows the smallest units of Figuren, and // marks the caesura between one Gedanke and the next.

The pattern of “breathe after the one” continues with a caesura after the high a, facilitated by fingering, and similarly after the g in the third bar. But the music imposes a new pattern, also clarified by my historically informed fingering, at the beginning of the last bar. Red f_p shows two more examples of Abzug.

Between the 1760s and the 1780s, the standard Good/Bad descending fingering for harp 12323232 (familiar also from 17th-century Spanish harp technique) is gradually superseded by Join/Separate fingerings using all four fingers. You start with the thumb, and the last, lowest four notes get 1234. In between, you use as many fingers as needed for the number of notes you have. So a seven-note descent would be 123 1234.

The adjustment takes place at the upper end of the scale, so that the last, lowest notes use all four fingers 1234. This results in a distinctive fingering for a five-note descent, in which you hop the thumb: 1 1234. [Fully-fingered sources feature a LOT of repeated thumb-strokes in this period.]

EXAMPLE 5 Mozart/Cousineau

In Example 5, I apply Cousineau’s (1784) fingering principles to Mozart’s (1778) descending scales in parallel tenths: This fingering encourages “breathe after the one” between the two Figuren of the first bar, shown by my changes to the beaming. The octave leap indicates a stronger “breathe after the one” between two Gedanken, shown by my // caesura mark.

It would not be inappropriate to use ‘old-fashioned’ 32 descending fingerings. These would ensure correct Good/Bad relationships, but would leave the player to create Join/Separate between Figuren.

EXAMPLE 6 Mozart/Meyer

Contrariwise, ‘fashionable’ Cousineau-type fingerings (mentioned as an alternative by Meyer 20 years earlier, so certainly not excluded from Mozart’s Concerto) prioritise Join/Separate, and leave the player to take care of Good/Bad. As Leopold Mozart makes clear in his detailed instructions for varying the pressure from note to note, within a single bow-stroke, 18th-century music requires both Good/Bad and Join/Separate.

What about the Bass?

Period sources pay great atttention to the continuo bass. The second edition of CPE Bach’s Versuch has an additional and longer book, 355 pages entirely devoted to Generalbass, including a final chapter which extends realisation of a continuo-bass towards improvisation of a free Fantasia.

Modern harpists tend to focus on the right-hand melody, viewing the music from the top down. Baroque music is constructed from the bottom upwards: the bass is no mere accompaniment, but rather provides the fundamental framework of rhythm and harmony that defines the structure for the ornamental melody. The heritage of Renaissance polyphony is that music is woven from the strands of individual ‘voices’; each strand has its own integrity, character and logic. The typical texture of Baroque music is the polarisation of treble and bass, i.e. 2-voice polyphony with a continuo-realisation filling-in the mid-range.

From the beginning of the Baroque period (Agazzari 1607) to the transition into the Classical (Leopold Mozart 1756), period sources assign to the bass the role of maintaining Tactus. The continuo does not follow the soloist, rather the bass creates a dependable rhythmic structure – like the rhythm section of a jazz-band. As with a jazz-band, it is acceptable for a baroque soloist not to be together with the bass, for the sake of elegant expressiveness around the steady groove: it is not acceptable for the groove to falter. See Monteverdi & Jazz. This is of course the opposite of today’s standard practice, even amongst most Early Music ensembles.

Harpists, lutenists and keyboard players must combine the roles of soloist and bass-section in one person. Modern players might need reminding to play the bass more strongly (as an equal partner), and to maintain the bass rhythm in Tactus (whatever technical challenges, complex ornaments, or expressive moments the melody might have).

Flow

My research in Consciousness Studies suggests that the optimal strategy could be to place one’s conscious attention on the bass, focussing on tight connection to the steady Tactus. Assuming sufficient advance practice, the melody can be better left to the unconscious mind, letting the fingers ‘do it for themselves’. Trills, for example, go better when you don’t think about them. Like a hypnotist’s swinging pocket-watch, or a meditation mantra, the constant down-up of Tactus (physically enacted in rehearsal, or imagined in solo performance) entrains the mind into Flow.

The paradoxical instruction to “Listen more than you play” can help the mind find that state of consciousness where mindful Observing facilitates ‘personal best’ performance, without a conscious sense of Doing. In baroque music, you can achieve this by “being the continuo-player”, creating the rhythm whilst listening to the solo (even though, you are actually playing that solo yourself).

Imagining, or even physically beating, a complete Tactus (down-up) to start yourself off (i.e. give yourself “a bar for nothing”) is an excellent way to connect yourself to the power of Tactus, to the Music of the Spheres, as you start to play.

What to do with Long Trills?

In a word, practise. Long trills are described in detail in all the mid-18th-century sources under discussion here. Harp sources admit that they are difficult, and they are more difficult still on modern harp.

So practise. Practise trills non-metrically, with a long appoggiatura, and then repercussions accelerating from slow to fast and all the way into the final turn and last note.

Then practise this beautifully shaped trill, whilst playing a simple bass in crotchets. The bass maintains Tactus, the trill is not aligned note-for-note with the bass, but you find the last note simultaneously. If the trill is long enough, combine it with messa di voce. But don’t try to be super-loud whilst trilling, and don’t try for too many reiterations. Shapeliness in the trill, and Tactus in the bass, are the priorities.

Frederick the Great plays a flute concerto in Sans Souci Palace. CPE Bach accompanies at the harpsichord, Quantz looks on at his pupil’s performance.

What is Abzug?

This is another central concept in period discourse about ornamentation. Literally “pulling off”, Abzug is the forte/piano contrast between an appoggiatura and its main note.

Leopold Mozart describes it as sliding into, sneaking into the main note (see the music examples above). Quantz describes a slight swelling of the sound on the ornamental note (so not an aggressive attack, but a slow-blooming sound; for violin a slow bow-stroke), with a smooth, soft transition into the main note.

On lute, one could literally “pull-off” from the fingerboard with a left-hand finger, in order to play the main note without any plucking action of the right hand. On harp, we can imitate this with a slow but firm finger-movement on the ornamental note, and a very passive action on the main (second) note, avoiding any articulate start-noise whatsoever.

Practise it.

The same forte/piano effect is needed every time from dissonance to resolution, as well as for any melodic moment with a pair of notes that function like a written-out appoggiatura. In the first music example above, as well as the Abzüge marked in red for explicit appoggiaturas, a subtle version of the effect is needed in the second bar on the high c-b, a-g, and (especially) f#-e pairs, and on the b-a pair at the end of the previous bar.

You need Abzug again and again. CPE Bach considers this the most important element of ornamentation. Indeed, the entire repertoire of the Empfindsamkeit period is characterised by the sensitive gesture of Abzug: every piece is full of opportunities to apply it. A missed Abzug is like marching into San Souci Palace in your muddy boots – you have just trampled on what should have been an occasion for the most elegant sophistication.

Appoggiatura onto a Triplet?

The standard rule is that the appoggiatura takes half of the value of the written note (two-thirds, if the written note is dotted). So the realisation of an appoggiatura onto a triplet divides the first note in half. But the more important element is – all together now: the Abzug. The appoggiatura itself needs a slow bloom, and the written note is soft; the remaining two notes of the triplet should be light, since they are Bad notes. It should sound like “Play-a Trip-let”, not “Da doo-ron-ron”!

EXAMPLE 7 CPE Bach

The (appropriate) tendency to lengthen the appoggiatura results in a rhythm that approaches the sound of a quadruplet, though still with the first note louder and slurred to the second. Some sources recommend this quadruplet realisation, others condemn it. Best practice is probably to keep some semblance of a triplet, but with a nice long appoggiatura and plenty of Abzug.

How to play a Short Trill?

There are lots of short trills in this repertoire, and longer or turned trills can legimately be simplified into short trills. So it’s a significant element of the style and a most useful skill to acquire.

The historical fingering is 2311, and the Abzug requires a decrescendo from first note to last. CPE Bach recommends you to schnellern (quicken, enliven) the first note, to make the ornament crisp and light. It should sound like “Tickle my toes!” and not “before the beat“.

EXAMPLE 8 Short Trill

Short Trills in Mozart

Practise this until you can fire off a whole chain of ‘flying short trills’ as Genlis (1802) teaches and Mozart requires. [The link is to the second edition of 1811].

Genlis’ second example (above) is not a realisation of the first example, but a preliminary exercise for those ‘flying trills’, at half speed and with extra time between each Figur.

As Genlis explains: ‘the two slurred notes are done by sliding the thumb on these two strings’. What I deduce from the third thumb stroke that follows each time (where one might have expected finger 2), is that after the two slurred notes, the sliding thumb comes to rest against the next string (continuing the movement onto the next string helps the slide flow nicely). At this point the exercise takes extra time, to teach you to apply a caesura here, before starting the next Figur. When you do restart, your thumb is already placed on the string you are going to need.

For the real thing, the full speed ‘flying trills’, each Figur starts with an upbeat, continuing the pattern of the first two notes. As one would expect from Muffat and others, the trills are on the Good notes – this is confirmed at the end of the sequence.

Mozart introduces his flying trills with a preliminary longer trill, turned so that its Figur ends on the second (crotchet) beat of the bar. The autograph staccato on this d indicates “Last note short”, allowing you to “Breathe after the one”. The staccato on the following c indicates it is an upbeat, and the Gedanke is now Genlis-style flying trills, each Figur having an upbeat to a Good-note trill.

EXAMPLE 10 Mozart/Genlis

This upbeat pattern continues into the next bar, which has rapid Alberti 64 harmonies in the left hand and bold downward leaps in the right (first you must “breathe after the one”), leading to a whole bar Long Trill over the same rapid Alberti pattern, now on the dominant seventh.

All these fireworks signal the end of the movement. After this comes the improvised cadenza (Quantz’s Easy and Fundamental Instructions show how 2 players can improvise together) and final tutti.

Short Trills in Handel

There is a tricky short trill on a dotted note in the Handel Concerto. Although it is difficult to execute this correctly in the time available, it should start with upper auxiliary (not the main note) on the beat (not before), so that the complete Figur has the crisp sound of a demanding publisher: “Prrrint today!” [the rolled r represents the repercussions of the trill] and not a lazy: “What about next week?”.

EXAMPLE 11 Handel

How should I damp?

This is a harp-specific question, and is discussed in several period Harp treatises, but with insufficient detail. The suggestions below are based on my personal experience.

For modern harpists, you might first consider threading a strip of felt through the very lowest strings – you don’t actually play these in Baroque pieces, and it might be better to lose the excessive resonance that they add.

Second, learn the Baroque way to damp by having your finger (and/or thumb) return to the string after playing (same finger, same string). This allows you to damp specific notes really quickly, rather than moving both hands to cuddle the strings and damp the whole instrument, which is very slow. You can damp individual notes or entire chords, in either hand.

Sometimes you can add rhythmic energy by damping where a rest is written on the beat. Damp crisply, precisely on the beat, even get some percussive noise from your fingers contacting the sounding strings.

EXAMPLE 12 Handel

Sometimes you need to damp to control bass resonance. If you damp between each note and the next, you produce a staccato effect: this would not be the optimum phrasing for movement by step.

But if you play, play the next note and then quickly damp the previous one, you produce a strong effect of legato.

You can mix these two ways to damp [legato, staccato] in order to create legato pairs, each pair separated from the next. This long-short sound is appropriate for Good/Bad.

EXAMPLE 13 Handel

The last note of any phrase could be damped, to make it short. If you play it without accent (as you nearly always should), the damping will be less abrupt, and might not even be necessary.

Any upbeat could be damped to create a “silence of articulation”, this throws the accent onto the next note.

Often you will need to damp to clarify a rising melody in the bass. This frequently applies at perfect cadences, if the dominant rises to the tonic; but it can also occur at the beginning of the phrase.

The bass cadence with an octave leap on the dominant implies staccati for that octave leap.

In every instance, you can adjust the damping [legato or staccato, and how much] to produce the most appropriate phrasing.

EXAMPLE 14 Handel

Combining all these techniques results in a LOT of damping, subtly adjusted, for various desired results. Such frequent damping is supported by the (limited) historical information available. The greater resonance of the modern instrument makes damping even more necessary than on baroque harp.

Damping with the left hand can establish the “groove” of a dance, or a dance-like movement. In the third movement of the Handel Concerto, the groove is the reverse triple metre, short-long, quaver-crotchet. You can make this energetic and clear by playing the downbeat strong and damping crisply, to produce a repeating groove effect that sounds like the words “Short Phrases”.

Notice how the semiquavers create a Figur across the bar-line, “breathe after the one”: both hands have a short note in the long space of the downbeat, but for different reasons.

EXAMPLE 15 Handel

All this takes practice. You need to train your ears and hands simultaneously, to hear the need for, and effect of damping, and to create the effects you want.

How to simplify Ornaments?

Period sources recognise that it is harder to play trills on harp, than on harpsichord. It’s even harder on modern harp than on baroque instruments. So it can be a great help to simplify ornaments. Certainly, it is better to simplify the composer’s ornament, than to omit it, to play it wrongly, to play the wrong type of ornament, or (heaven forbid!) to play an ornament without Abzug.

In place of a long trill with initial appoggiatura and final turn, you can make things easier for yourself with these three steps (in this order of application):

- Reduce the number of reiterations of the trill.

- Omit the final turn

- Omit the initial appoggiatura

If you needed to apply all three three steps, you will be left with a Short Trill, and you should have practised this sufficiently to be confident in it for any eventuality.

If you are really under pressure, you can convert a turned Trill into a simple Turn (upper auxilary, main-note, lower-auxiliary, main-note). Make the first (upper) note long and remember the Abzug.

It’s not so good to change a Short Trill into a simple Appoggiatura, because the Short Trill is meant to sound lively and brilliant, whereas the Appoggiatura should melt, languishing. A Turn could be a better solution: there are still four notes to play, but the fingers can manage them faster. For a fast Turn, try 1231, which should come out crisper than 1232.

How does Continuo-experience help one’s Solo-playing?

The great harpsichordists and composers of the baroque were also expert continuo-players: JS and CPE Bach lead the way!

The best way to progress rapidly as a harpist or keyboard-player studying baroque repertoire is first to acquire basic continuo skills. Playing in ensembles will inform your ears and mind, with the opportunity to hear the same fundamental principles applied in subtly different ways by different instruments and voices. Ensemble-playing also provides an energetic group dynamic and a supportive social group, and gives access to exciting large-scale projects. Don’t miss the chance to play in a baroque opera or orchestra.

As a continuo-player, you can adjust realisation to your (gradually increasing) level of skill, contributing something useful right from the start, without needing to be exposed as a soloist until you are ready.

For harpists, a single-action harp is likely to be accepted by HIP training-ensembles, even in 17th-century repertoire, and for a modern player presents less of a barrier to immediate gratification: double and triple harps are more challenging. It is to be hoped that an open-minded training ensemble would admit a keen student even on modern harp, either as a stepping stone towards baroque harp, or as a way to gather experience for solo-playing on the modern instrument.

The experience of playing continuo will transform your view of the role of your left hand. And the continuo-player’s view of ensemble music, from the bottom upwards, is the best approach to baroque solo-playing.

Familiarity with figured and un-figured basses will consolidate your understanding of baroque harmony, and help you recognise the character of dissonances and sequences: the excitement of rising 5 6, the subtleties 6 5 and 5b dissonances, the sweet melancholy of chains of 7s.

EXAMPLE 16 Handel

How can I give my performance more clarity and more character?

See above: Tactus, Good/Bad, Join/Separate.

For harpists: damping. For modern harpists, a basic position somewhat près de la table: for baroque harps, this position is standard.

For anyone: “Long notes long, short notes short”, and “Last note short, no-accent”. Ornaments on the beat. Contrast one Figur with the next.

How can I make my performance more expressive?

See above. Sensitise yourself to the flavour of each dissonance, and show the tension-release of each dissonance-resolution.

For harpists, move your fingers down, even more près de la table, for a dissonance, and up (higher than normal) for resolution. A basic position somewhat près de la table results in small changes down or up making a big difference to tone-colour.

Apply Abzug to appoggiaturas. Search for the particular character of each Figur.

Should I play marked Repeats?

Yes.

Should I add Rallentando?

No.

Muffat and Leopold Mozart clearly state that the same tempo should be maintained from beginning to end. There is historical evidence for rallentando, but not in dance-music, and perhaps only when it is specifically notated. It tends to occur where the note values get smaller and smaller at the end of a section; or where there is a final cadence after a silence (e.g. Hallelujah Chorus). Meanwhile, Leopold says simply, keep exactly the same tempo from beginning to end.

Remember, “what everyone does today” and “my favourite CD” are NOT historical evidence. Leopold Mozart is.

If you are keen to add rallentando, find a source to support your wish. [Student challenge!] But… also beware of the temptation to look into the sources to support a decision you have already taken. A better strategy is to read the sources with an open-mind, and then decide. If you read the whole of Leopold Mozart, you will have plenty to think about and apply, before you need to go looking for another source in order to explore exceptional cases and outlier opinions.

Summary

18th-century style calls for a enormous amount of short-term detail, many contrasted Figuren, many presentations of dissonance-resolution, and many, many Abzüge. All the while, you maintain the groove of steady Tactus in the bass.

Harpists: see my article on Empfindsamkeit and Single Action harp.

Historically Informed Performance is not what I say, not what Early Musicians do today, not what you hear on CDs, but performance based on historical information. Use IMSLP to get original scores, and use the mighty Versuch publications as reference books to answer your performance practice questions. Harpists: read Meyer, Cousineau and (for elite soloist-level skills) Genlis.

Try to establish a habit of checking what you are told (including what you have read here!), and checking your own assumptions. The state of knowlege advances when someone has the courage to question the status quo.

Dare to be different!