Tactus is the slow, steady beat that guides Early Music, shown by a down-up movement of the hand, approximately one second each way. In previous posts, I’ve introduced the concept Rhythm – what really counts?, explored the philosophical background Quality Time: how does it feel?, and summarised the implications for Historically Informed Performance Tempus Putationis: getting back to Monteverdi’s Time.

In this article the focus is on the Tactus Hand itself, on the practicalities of embodying a mystic concept that links everyday music-making with the divine power of the cosmos. And we should not underestimate that power, since, for renaissance and baroque musicians, the Tactus Hand was the Hand of God made visible in microcosm.

Tactus in the 1980s

Since the 1980s, as co-director of ensemble Tragicomedia and in my own teaching and directing, I have frequently used a simple arm-waving exercise to give participants a practical experience of Tactus. I emphasise the significance of a two-way motion with a sense of ‘swing’, as opposed to the hammering effect of a one-way beat. I recommend using the entire arm, a long pendulum for a slow swing. And already in those days, I noticed that this kind of Tactus work brought to the group a special atmosphere of calm and concentration. After just a minute or so of beating Tactus, the room seems quieter, each of us more aware of small sounds and as a group, better able to find a united sense of rhythm and timing.

In my own playing, I notice that keeping my mind on the Tactus allows me to stay calm, even in demanding fast passage-work. No matter how fast my fingers need to move, my inner focus is on that slow swing: even the fast bits still feel slow and steady. Working with singers, I encourage them to feel the embodied power of the Tactus, to realise that they could hold the entire ensemble in their own hands, and to feel (like a physical weight) the responsibility that this entails. The Tactus-movement can’t be a trivial flip of the wrist, it needs the gravity of a long, weighty pendulum.

George Houle’s most useful survey of Metre in Music: 1600-1800 was published in 1987, though I didn’t come across it until many years later. Houle wondered what a tactus-directed ensemble would sound like: my work ever since has been devoted to answering that question.

Since the 1990s, with my own ensemble, The Harp Consort, we continue to apply Tactus to many different repertoires, to Spanish dances in Luz y Norte, to German high baroque in Italian Concerto, to the medieval Ludus Danielis and the first South American opera, La púpura de la rosa, to folk-music from Guernsey, Les Travailleurs de la Mer, to Purcell’s theatrical and chamber music in Musick’s Hand-Maid, to medieval popular songs Les Miracles de Notre Dame and Latin-American religious music, Missa Mexicana. In these and many other projects, Tactus is the organising principle that unites the whole ensemble in music, dance and improvisation.

Tactus in the 2010s

In this current decade, with my renewed focus on early opera, Tactus has been a key concept in the award-winning Text, Rhythm, Action! program of international research, experiment, training and performance. I’ve re-opened the investigation of Tactus in the context of the Historical Science of Time itself, and applied the latest research findings to my work on Baroque Gesture and Historical Action. Fascinating connections have emerged: the 18th-century love of fermata and cadenza seems to match the contemporaneous fashion for striking Attitudes on the theatrical stage.

Some findings would seem glaringly obvious, but have previously escaped attention. Monteverdi, Shakespeare and their contemporaries circa 1600 did not share our present-day intuitive understanding of Absolute Time: that idea was introduced in Newton’s Principia (1687). The seicento concept of Time was Aristotelian, depending on movement to define ‘before’ and ‘after’. In music, that movement is embodied in the Tactus Hand.

Gradually, I’ve been able to reach a more refined understanding of Tactus as Time, Tactus as Movement, with the goal of applying all that pre-Newtonian philosophy to down-to-earth practicalities. How do we move our hands to create Tactus, and what does it mean?

For Italian music around the year 1600, the Tactus hand is indeed like a pendulum, swinging for about one second each way (i.e. two seconds for the complete there-and-back-again). The complete (reciprocal) movement corresponds to a semibreve, so each individual (one-way) beat corresponds to a minim, at approximately minim = 60. Of course, in Monteverdi’s day, although there were clocks that ticked approximate seconds accurate to about 15 minutes per day, clocks were not capable of defining those seconds accurately. So Tactus Time is only as accurate as you can humanly make it.

The precise Quantity of Time therefore can’t be defined: rather Tactus relies on each musician to remember how it feels, to recall the Quality of Time. So try these tests: can you remember the sound of a ticking clock? How fast does it tick (according to your memory)? Can you recall the speed of some particular piece of music that you’ve often performed with the same team? How accurately can you estimate a one-second pulse? If you hear a church clock strike noon, how good is your estimate of 1215?

Of course, nowadays, you can check your estimates against Absolute Time (well, at least against a digital stopwatch!). But the point of these experiments is to get used to the idea that

You are trying to feel the right Time

This is very different from the modern musical practice of performers choosing their own time. Seicento tempo is not a matter of personal choice!. You would not get much sympathy if you turned up late for rehearsal, saying “Although most people take it faster, in my interpretation, it is not yet 10 o’clock.” Toby Belch, in Shakespeare’s As you like it (1603) makes a similar connection between good time-keeping in everyday life (‘to go to bed betimes’) and keeping time in music. In reply to Malvolio’s accusation that he shows no respect of time, he retorts that ‘we did keep time, sir, in our catches’ (witty part-songs).

Your estimate of time will naturally be influenced by your surroundings and your own state of mind: if you are in a hectic mood, you might err on the fast side; if you are feeling particularly relaxed, you might err on the slow side. If you play a piece of music in a generous acoustic, you might play it slower; in a dry acoustic, you might play it faster to get the same feeling.

The precise Quantity cannot be defined – you are trying to find the right Quality

Fixing Tactus at the order of magnitude of one second (for C time in Italian seicento: in other repertoires, there are significant pulse-rates somewhat faster at approx 80 beats per minute or somewhat slower at around 45 bpm) does not imply a ‘metronomic’ performance. There is room inside that slow, steady minim beat for the subtle difference between Good and Bad syllables (in crotchets) or the dance-like swing of French inegalite (in quavers). There are also symmetries on longer time-scales, and good musicians will be sensitive to these too. Nevertheless, Tactus provides a particular time-scale, a calibration that synchronises musical notation with real-world time, with physical movement, and with the human body. That time-scale is approximately one second, corresponding to a pendulum-length of approximately one metre, which is approximately the length of an outstretched arm (measured to the centre of the body).

Narrowing down the historical sense of musical time to an order of magnitude might not seem like much progress towards the question of “what is the historical tempo for Monteverdi’s Orfeo?”. But even this very approximate measure can help unify an ensemble, by ensuring that everyone is feeling the same beat (as opposed to some counting in crotchets, others counting in minims). There has been some discussion along the lines that if a slow Tactus beat is good, then feeling a super-slow pulse (say 30, or even just 15 beats per minute) might be even better. But whilst there is evidence for very slow pulse in some medieval music, around the year 1600 ensemble unity was definitely organised on the Tactus time-scale at around 60 bpm.

Establishing an approximate calibration of real-world time to the speed of a minim in common time is also a vital first step towards understanding seicento Proportions. Whether or not a certain interpretation of the relationship between common and triple time is plausible, depends crucially on the starting tempo in common time. Somewhat illogically, current debate on Proportions recognises that historical notation was intended to fix the speed of triple metres (even if we do not yet have a consensus agreement about how to understand that notation), but resists the idea that the speed of common time was also fixed (as precisely as humanly possible). But Roger Mathew Grant’s Beating Time and Measuring Music shows how the entire system of Proportional notation depends crucially on common-time Tactus. The various Proportions are linked, like cog-wheels in a 17th-century clock, and calibrated to real-world time by setting common-time Tactus at the rate of one minim = one second (as precisely as humanly possible).

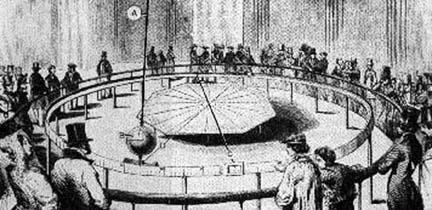

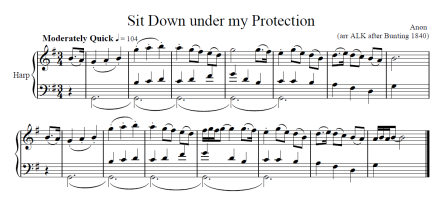

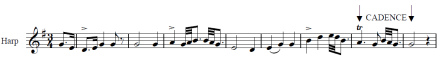

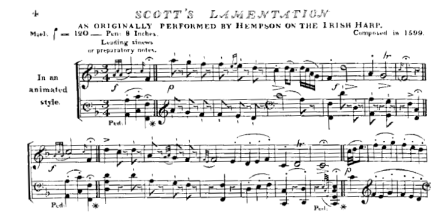

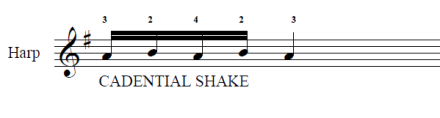

The pendulum effect, discovered by Galileo in the late 16-century but not built into a clock until 1656, was used to measure musical time by means of Loulié’s chronomètre (1696) and as late as 1840, in Bunting’s transcriptions of ancient Irish harp-music. With students from the Historical Harp Society of Ireland, we tried playing to a pendulum beat at Scoil na gClairseach: the experience is nothing like playing to a metronome click. Try it for yourself, and you’ll immediately appreciate the differences.

The movement of a pendulum, pausing momentarily at the end of each swing, leaves musicians a certain margin for subtle choice of where to ‘place’ the beat. To use the vocabulary of jazz, you can be ‘on the front of the beat’ or ‘laid back’. In this sense, a pendulum feels more ‘human’, less ‘mechanical’. However, the pendulum does not allow those subtle choices to pile up cumulatively: it checks any general tendency to rush or drag. Meanwhile, the strong but gentle movement of a pendulum has the same mesmeric effect of inducing relaxed concentration that we notice with the Tactus hand itself.

Down & Up

Re-reading seicento treatises reminded me that the Tactus movement is always described as down-up. So when using the Tactus hand as a rehearsal exercise, or in performances of Cavalieri’s (1600) Anima e Corpo at the Theatre Natalya Sats in Moscow, we abandoned the side-to-side swing in favour of the historical, vertical movement. This creates a subtle distinction between the two directions of movement, with Down having added significance, and facilitates awareness of the complete Tactus cycle, from Down to Down.

From my studies of historical swordsmanship, modern Feldenkrais Method and ancient Tai Chi, I can now appreciate that the sensation of ‘soft strength’ appropriate to beating musical time can be found by connecting the Tactus Hand down through the whole body. This requires a body-posture that maintains structural integrity with minimal tension. We can see such postures in period paintings and sculptures: a good posture for Tactus is also the starting point for Baroque Gesture, and for historically informed instrumental playing.

My training as a Hypnotist provides an explanation for the special sense of relaxation and concentration that focus on the Tactus can evoke. Following the lead of Milton H. Erickson (the father of modern hypnotism) and of Joe Griffin (theorist of the Origin of Dreams), it is now recognised that any experience of calm concentration can induce a particular state of mind. We can call this an Altered State of Consciousness, we can call it Flow or being in the Zone, we can call it Mindfulness or Meditatation: the labels don’t really matter. This phenomenon of heightened awareness is the key to optimal performance not only in music, but also in many other creative and sporting activities.

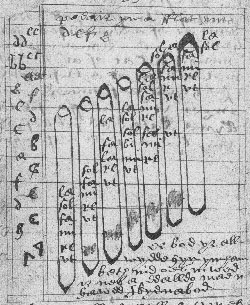

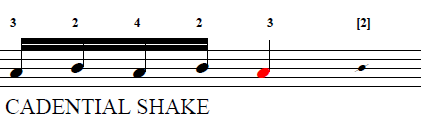

Preparing for the first performance in Russia of Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers, we encountered many instances of slow triple-metre, notated as 3 Sesquialtera semibreves in the time of the 2 common-time minims. This can be a tricky Proportional change, but Tactus helps us manage it, especially with a vertical motion of the hand. The duration of the complete cycle from Down to Down continues unchanged: the only adjustment is that Down now lasts longer than Up.

Sesquialtera: Down – Up becomes Down – 2 – Up

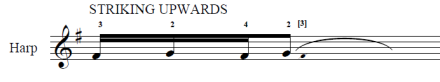

In Spanish baroque music, the same adjustment happens even more frequently, whenever we find the cross-rhythm of Hemiola amongst a regular metre of Tripla. A well-known modern example is I wanna live in America: two units of Tripla, I wanna / live in A- / (Down Up) have the same duration as one unit of Hemiola me-ri-ca (Down – 2- Up).

One way to negotiate such shifts is to de-emphasise the Up stroke so that it simply doesn’t matter whether it is equal (Down Up) or unequal (Down – 2- Up). Instead, the focus is on preserving the equality of measure in the complete cycle, a consistent time between Down strokes. This focus on the complete Tactus-cycle, on the common-time semibreve rather than on the minim of each stroke, is mentioned in some period treatises, and works well for us in practice.

Towards the end of last year, working with multiple Tactus-beaters for polychoral music, I suddenly noticed a small detail of Tactus-beating that had previously escaped my attention. In the three-choir piece illustrated on the frontispiece of Praetorius’ Theatrum Instrumentorum, the Tactus Hands are shown palm outwards.

I immediately searched through other period images and consulted with colleagues. Though no-one else had noticed it before either, it became apparent that Tactus-beating was usually, perhaps always, palm-outwards. (Do let me know if you find evidence to the contrary, or if you would like to add to the mountain of evidence in favour of palm-out).

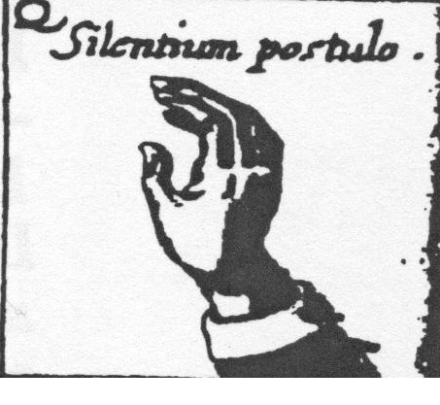

The historical movement of the Tactus Hand, down-up with the palm outwards, feels different, and subtly alters the relationship between the two strokes. And the connections to Baroque Gesture are highly significant. The starting position of Tactus (hand high, palm outwards) corresponds to the orator’s preparatory gesture, commanding the audience to be silent and listen. The powerful Down movement of the Tactus stroke corresponds to a gesture of authority, quelling and directing subordinates.

The period philosophy of the Music of the Spheres connects the perfect movement of the cosmos with the harmonious nature of the human body and with practical music-making. Similarly, heavenly Time directed by the Hand of God is reflected in the microcosm of the Human hand beating Tactus and in the perfection (to the limits of human ability) of musical rhythm. That rhythm is found by dividing the slow Tactus beat in various Proportions, just as the movement of the stars and planets are derived from the Primum Mobile. This concept is beautifully described in Dante’s Paradiso, Canto XXVII. Here is the classic Longfellow translation:

The nature of the universe, which holds

the center still and moves all else around it,

begins here as if from its turning-post.

This heaven has no other where than this:

the mind of God, in which are kindled both

the love that turns it and the force it rains.

No other heaven measures this sphere’s motion,

but it serves as the measure for the rest,

even as half and fifth determine ten;

and now it can be evident to you

how time has roots within this vessel and,

within the other vessels, has its leaves.

The Tactus Hand embodies the divine Hand of God; maintaining Tactus symbolises the turning of the cosmos; the movements of the Tactus Hand embody earthly authority and command listeners’ attention. However, the authority of Tactus is not located in the whims and fancies of an individual Tactus-beater: Tactus-beating is utterly different from modern conducting. The responsibility of a Tactus-beater is to recall and preserve the perfection of heavenly time, not to make personal choices. So it is that multiple Tactus-beaters can collaborate simultaneously, as Praetorius showed.

No-one is trying to make a personal interpretation of Time: everyone is trying to unite in finding the right time.

Some musicians feel a deep sense of responsibility to arrive at rehearsal on time. This is part of the respect we owe to the beauty and ineffable nature of Music itself. If you can understand such respect, then you might begin to understand the sense of high duty and precise timeliness that renaissance musicians felt about rhythm.

Music and other arts offer us earth-born creatures a glimpse of a world beyond the everyday. In period philosophy, the Tactus Hand allows musicians to touch the stars. We all know that Early Music was directed not by conductors, but by Tactus beaters. So why not try the Power of Tactus for yourself! I’m sure you’ll have a Good Time.

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our websites:

http://www.TheHarpConsort.com [the ensemble, early harps & Early Music]

http://www.IlCorago.com [the production company & Historical Action]

http://www.TheFlow.Zone [Flow for optimal creativity, The Zone for elite performance]

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago. From 2011 to 2015 he was Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions. He is now preparing a translation of Bonifacio’s (1616) Art of Gesture and a book on The Theatre of Dreams: The Science of Historical Action.