These representations in music, a spectacle truly of princes and moreover most pleasing to all, as that in which is united every noble delight, such as the invention and disposition of the tale;

sententiousness, style, sweetness of rhyme;

art of music, concertos of voices and instruments, exquisiteness of song;

grace of dance and of gesture.

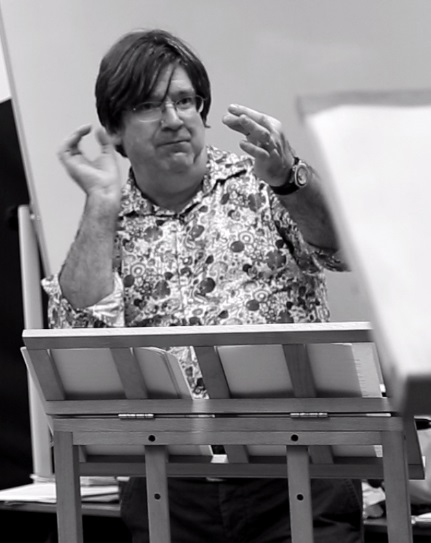

Landi “La Morte d’Orfeo” (1619) First Staged Production i Modern Times International Baroque Opera Studio (2013)

This paper was presented at a recent Collaboratory “Languages of Emotion”, organised by the Australian Research Council’s Centre for the History of Emotions. More about CHE here.

The earliest-surviving opera, Cavalieri’s Anima & Corpo (1600) has just notched up three seasons in repertoire at the Theatre Natalya Satz, Moscow (the original home of Peter and the Wolf) in Georgy Isaakian’s modern yet highly sympathetic production, which won the 2013 Golden Mask, Russia’s most prestigious music-theatre award. Over the years, new singers, musicians and continuo-players, even the Theatre’s brand-new Chorus have joined the show, so we have been constantly in rehearsal, continuously developing the performance.

Georgy Isaakian: Three “texts” to be delivered

In a rehearsal break last year, Georgy commented to me that in opera, the libretto, the music and the stage production are each “texts” for the performers to deliver, each of which tells its own story. In the context of modern opera direction he is absolutely right. And we might paraphrase his comment for the purposes of this discussion, to claim that Text, Music and Action are each “languages of emotion”, “languages of performance”.

But that 17th-century theatre director, Il Corago, would fundamentally disagree with the second part of Georgy’s remark, that Text, Music and Action each tell their own story. In the 17th-century productions, the same story was told simultaneously in all the languages of performance. Rather than any particular detail of historical accuracy, I would argue that it is this unity, this telling of the same story, that should today distinguish a historical production from a ‘modern’ one, and it is that simultaneity which will make a historical production a good one, in the sense of being effective for the audience.

The imitation … must take into consideration only the present, not the past or the future, and consequently must emphasise the word, not the sense of the phrase.

Monteverdi Letter to Striggio 7 May 1627

Thus all the languages of emotion are aligned and synchronised in performance, like the co-ordinated pulse of a laser-beam, to move the passions muovere gli affetti of the audience. As composer, Monteverdi is praised for

adapting in such a way the musical notes to the words and to the passions that he who sings must laugh, weep, grow angry and grow pitying, and do all the rest that they command, with the listener no less led to the same impulse in the variety and force of the same pertubations.

Anon Argomento to Le Nozze d’Enea in Lavinia (c1640) cited in Tim Carter Monteverdi’s Musical Theatre

Note that it is the words, or perhaps even more fundamentally, the passions, that ‘command’. And notice the connection between ‘variety’ i.e. dramatic contrast and the emotional ‘force’ of the performance. In the Preface to Anima e Corpo, Cavalieri is particularly insistent on such variety, a crucial difference to the 19th-century approach of intensifying one particular emotion until the cathartic moment is reached.

It’s obvious that in good poetry, each particular image should create an appropriate metaphor for the underlying message. But the sound of the words too should be appropriate, as Dante observed as he descended into the last circle of Hell:

If I had rhymes both rough and stridulous,

As were appropriate to the dismal hole

Down upon which thrust all the other rocks,

I would press out the juice of my conception

More fully; but because I have them not,

Not without fear I bring myself to speak;

Actually, Dante manages quite well to find suitably “rough and stridulous”sounds, such as occe and uco:

S’io avessi le rime aspre e chiocce,

come si converrebbe al tristo buco

sovra ‘l qual pontan tutte l’altre rocce,

io premerei di mio concetto il suco

più pienamente; ma perch’io non l’abbo,

non sanza tema a dicer mi conduco;

Dante Inferno 32

Even in instrumental music, Agazzari requires instruments to imitate the emotion and semblance of words, imitatione dell’affetto e semiglianza delle parole. (More on Agazzari’s continuo treatise Del Sonare sopra’l basso (1607) here).

Meanwhile, a singer’s acting also has to match the emotions:

When she speaks of war she will have to imitate war; when of peace, peace; when of death, death; and so forth. And since the transformations take place in the shortest possible time, and the imitations as well – then whoever has to play this leading role, which moves us to laughter and to compassion, must be a woman capable of leaving aside all other imitations except the immediate one, which the word she utters will suggest to her.

Monteverdi, ibid.

As Shakespeare has Hamlet tell the Players, “Suit the Action to the Word”. And this will be matched in the music:

[She must] be fearful and bold by turns, mastering completely her own gestures without fear or timidity, because I am aiming to have lively imitations of the music, gestures, and tempi represented behind the scene; … the shifts from vigorous, noisy harmonies to soft, sweet ones will take place quickly, so that the words will stand out very well.

Monteverdi, Letter to Striggio 10 July 1627

Text, Music and Action must be united:

They make the steps and gestures/actions in the way that the speech expresses, nothing more nor less, observing these diligently in the timing, hits and steps, & the instrumentalists [observe] the aggressive and soft sounds; and the Text [observes] the words in time, pronounced in a manner that the three actions [fight, music, text] come to meet each other in a unified representation.

Monteverdi, Preface to Combattimento 1636

All of this proceeds from the Rhetorical principle of Decorum, that every element should be suitable, appropriate to its rhetorical purpose. As we already observed, the starting point is the emotions embedded in the Text. In a 17th-century opera house, there is a single artistic director, Il Corago, who has “universal command” over every aspect of production, but is ‘subject to the text’. The anonymous c1630 book Il Corago therefore devotes considerable attention to the requirements for a good libretto. Advising how to put on a good music-drama, Cavalieri’s Preface to Anima e Corpo similarly concentrates on the libretto, and we saw how Monteverdi carefully negotiates with his librettist, Striggio, in order to get a libretto that will give him the dramatic and musical opportunities he needs.

With the madrigalism, or ‘word-painting’ so typical of this period, composers ‘paint’ the emotion of a particular word, synchronising the musical effect with the text. This was one of the toughest challenges, as we translated the libretto of Anima e Corpo into Russian: we had to preserve the word-order of the original Italian, so that Cavalieri’s musical effects would still coincide with the correct word.

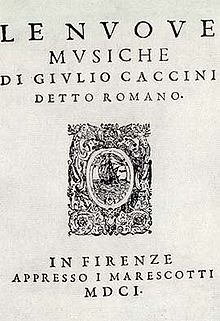

I’ve written here and here about the importance of rhythm in 17th-century music. As Caccini writes in Le Nuove Musiche (1601), music consists of “Text and Rhythm, with Sound last of all.” But rhythm is also crucial for period gesture.

The thunderbolts of Demosthenes would not have such force but for the rhythm with which they are whirled and sped upon their way.

Quintilian, citing Cicero

The motions of the body also have their own appropriate rhythms

Quintilian

Demonsthenes, Cicero, Quintilian

This rhythm is synchronised also with the words, and with the emotions themselves:

The movement of the hand should begin and end with the thought that is expressed. Otherwise the gesture will anticipate or lag behind the voice, both of which produce an unpleasing effect.

Quintilian

Action, Music and Text are not only unified, but also synchronised.

Every gesture and every step should fall on the beat of the sound [i.e. music] and of the song [i.e. text].

Marco da Gagliano Preface to Dafne 1608

LANGUAGES OF EMOTION?

It’s tempting to go along with the idea that music is a language, “nature’s voice, through all the moving wood of creatures understood, the universal tongue to none of all its race unknown”, as Purcell’s St Cecilia Ode (1692) proclaims. Music does have a kind of grammar, with certain Parallels of fifths and octaves to be avoided, Cadences that function rather like punctuation, and Ordered Chunking of Preparation-Dissonance-Resolution that could be compared to sentence-order of subject-verb-object. We can discern some meaning in the emotional contrasts of music, and particularly in the word-painting of 17th-century madrigalism, but we cannot translate precisely between music and text in the way we can between English and Italian.

In 1644, John Bulwer makes extravagant claims that gesture is a language. “This naturall language of the Hand” does have a “significant varietie of important motions” but it’s hard to find here any grammar, unless one counts the rule of avoiding the left hand (or at least favouring the right), in all but highly negative gestures. In L’arte dei Cenni (1616) Giovanni Bonifaccio similarly claims that the “visible speech” or “mute eloquence” of gestures (here not limited to the hand, but extended to the whole body from head to toe, not omitting “gestures of the genitalia” – you’ll have to read it for yourselves!) is a universal language.

The meanings of gesture are supposedly clear and universal, but in practice gestures are often incomprehensible – you might not recognise the gesture that “explains more subtill things” or another that “inculcates Logick, as with a horn” – or local. The street-theatre players with whom I appeared in a medieval show on tour around Greece found out the hard way that the friendly thumbs-up gesture with which they saluted the audience has a local meaning corresponding to the middle finger in other countries, or the V-sign in England.

Even in their own period, Bulwer’s and Bonifaccio’s claims obviously fail. Yet there are so many close parallels in their work, that we might consider accepting the idea of a ‘universal language’, if we confine their ‘universe’ to the narrower domain of the Western European, Christian, educated, middle and upper social classes of their readership, who shared a common background of Biblical and Classical literature, whether they were English or Italian. After all, any language is only a language for those that understand it, otherwise it is just meaningless noise. And a meaningful word in one language may be just noise, or have a different, even an obscene meaning, in another. My favourite modern example is the Vauxhall car, the Nova, which sold very badly in Spain. In Spanish, no va, means “it doesn’t go”.

So, since we have seen that Music and Gesture are closely aligned with performed Texts, in particular with the Emotions of those Texts, let’s side-step any debate over “what is a language” and look at each of these ‘languages of performance” to see what they can say about Emotions in early opera. Can we ‘translate’ between them, perhaps not in quite the same way we can translate between English and Italian, but with sufficient precision to extract emotional meaning? As many CHE researchers have commented, Emotions studies are necessarily “messy”, and inherently holistic. We have already seen that Text, Music and Action are complexly interconnected. So performers must try to isolate particular elements that they can work on in rehearsal, and prioritise amongst all the possible options.

TEXT

- From the Text performers can extract factual information: Io la Musica son, I am Music. Da mio Permesso amato a voi ne vengo, I come to you from Permesso. Incliti eroi, sangue gentil de regi, the audience is honoured as famous heroes, noble blood of kings.

- The Text also gives cues for specific emotions: tranquillo calm, turbato agitated, nobil ira righteous anger, amore love, infiammar fired up, gelati menti frozen minds– all these in one four-line stanza.

- Text also shows the character of the speaker: “with this golden harp I’m accustomed to charm mortal ears, but with the heavenly lyre I can even involve your souls.” All these examples come from the Prologue to Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607).

Information, Emotion and Character are the Rhetorical divisions of Logos, Pathos and Ethos, which correspond also to three 17th-century performance options.

- A text may be read appropriately, but without personal involvement, as a modern newsreader would adopt a suitable tone for a serious report, whilst preserving a proper professional detachment.

- A performer can invest more emotion in the delivery, in the manner of a fine poetry-reading, but without identifying themselves with the subject of the piece. So a woman might read a poem in the male voice, or a vocal ensemble perform an amorous madrigal.

- But around 1600 in both Italy and England, there is a fascination with the genere rappresentativo, with embodying a character in dramatic music, with what Shakespeare’s contemporaries called Personation.

But in whichever mode the performer communicates a Text, the movement of the passions that concerns us is from the text to the audience. It is not about performers expressing their own emotions – this is an essential difference from the romantic tradition – even if performers, like audiences, get swept along by the passions that are constantly on the move.

MUSIC

Music as Caccini tells us is Text, Rhythm and Sound. This sets the first priority as

- Articulation, the clear enunciation of the words by a singer who should

seek to chisel out the syllables so as to make the words well understood, and this is always the chief aim of the singer in every occasion of song, especially in reciting. And be persuaded that the true delight arises from the understanding of the words.

Marco da Gagliano, Preface to Dafne 1608

For an instrumentalist, Articulation means creating speech-like patterning by means of keyboard, harp or lute fingering; bowing on violins or viols; and tonguing on wind instruments. This creates Agazzari’s ‘semblance of words’, giving opportunity for the passions of the words to be imitated too.

2. Rhythm in this period is structured around regular Tactus and mathematically precise Proportions, inside which the accented and unaccented syllables of renaissance poetry can be pronounced Long and Short. (These syllables are often referred to as Good/Bad, but Caccini and others refer to them as Long/Short. In spoken Italian, Good syllables are usually lengthened anyway).

3. Period writers discuss the Sound of early opera as Harmony, in particular processes of dissonance and resolution, and Modulazione, the imitation of speech contours as the ‘melody’ for recitatives. In the Preface to Euridice, composer, harpist and tenor Jacopo Peri praises the emotional effectiveness of these speech-like elements, as opposed to the old-fashioned style of beautiful singing and elaborate ornamentation, as championed by soprano Vittoria Archilei.

Vibrato – the topic that dominates many discussions today – is simply not on the agenda of serious aesthetic debate: there are simple rules for applying it, just as there are for other types of ornament. At the end of a long Good note. That’s it, basta, The End.

Plain note (with messa da voce),

Waived note (with messa da voice and late-arriving vibrato)

Trillo (with accelerating trill and diminuendo)

Roger North (1695)

cited in Greta Moens-Hanen

Das Vibrato in der Musick des Barock

ACTION

We could similarly classify Action, perhaps from small to large, from

- what Bonifaccio calls cenni – outward and visible signs of inner passion, i.e. gestures, facial expressions, small movements;

- large-scale postures and movements of the whole body – positioning on stage, walking onto stage or around the stage, dance, sword-fighting, costumes; and

- stage sets, backdrops, lighting.

We’ve just presented Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers, in a version strongly influenced by CHE research, and as the first-ever performance in Russia, and this brought to my attention that 17th-century religious liturgy also includes Action of all these classes.

RHETORIC

Passions are Nature’s never-failing Rhetorick, and the only Orators that can master our Affections.

The English Theophrastus (1708)

As languages of performance, Text, Music and Action are governed by the canons of Rhetoric. As we consider the communication from performer to audience we are concerned not so much with Invention (even if performers in this period often improvised) and Arrangement, rather with Style, Memory and especially Delivery. From the perspective of a History of Emotions, we are less concerned with what is said, than with how you say it. After all, the meaning of bare words is only the tip of the emotional iceberg: “I just asked her what time dinner would be ready, and she flew into a rage”.

Simply moving the word accent, fundamentally changes the subtext:

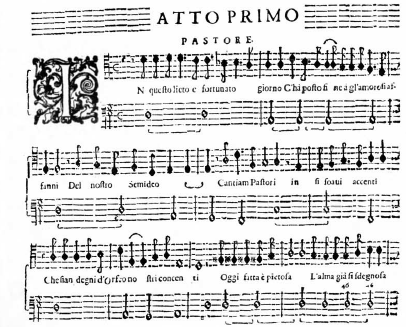

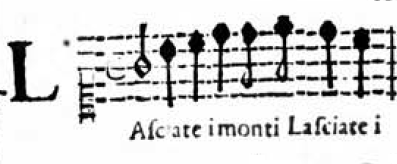

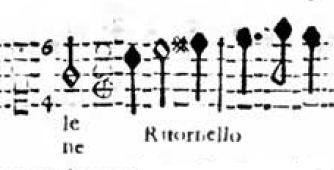

“What are you doing?” [neutral] “What are you doing?” [you, not me] “What are you doing?” [don’t just think about it] “What are you doing?” [disbelief] “What are you doing?” [exasperation]. A musical setting might underline one or other choice. Thus in the opening speech of Act I of Orfeo, “in questo lieto e fortunato giorno“, Monteverdi underlines the emotional words ‘happy’ and ‘lucky’, rather than the neutral fact of ‘this day’.

Gesture also underlines particular words and clarifies meaning. Alan Boegehold’s When a Gesture was expected provides “a selection of examples from Archaic and Classical Greek literature” of when a gap in the Text would have been filled by a Gesture. In seicento opera, Gesture is expected on many often-encountered words, especially on Deictics, pointing words. The frequent use of the most powerful deictics – Here! Now! Me! – in early opera points to the frequent and emotionally powerful use of Gesture, and suggests immediacy.

DEICTICS – pointing words “Here!” “Now!” “Me!”

Pointing gestures:

To show, indicates, refers to self

Other Gestures that might seem optional or unfamiliar to us would fit almost automatically into a 17th-century hand. “To be, or not to be, that’s the question” – the famous Words suit the Actions (less well-known today) of Bulwer’s “distinguish between contraries” and “pay attention”. To any gentleman of Shakespeare’s time, these movements are utterly familiar to the hand as a rapier swordsman’s disengage from quarta (Mercutio’s punto reverso) to to seconda, followed by an attack in terza (Mercutio’s stoccata) – “a hit, a very papable hit”!

Traditionally, historical musicology has used Text to explain the Music set to it. Insights gleaned from such studies have informed today’s performers. In contrast, it has been widely assumed that we don’t know enough to attempt to reconstruct period Action, and/or that the attempt would be meaningless for a modern audience. I strongly disagree. We have lots of information, albeit as a series of stills. But study of period dance, and more recently of historical swordsmanship, can help us “join the dots”. But the difficulty is that putting your hand in the right place is not sufficient. Good gesture requires exquisite timing and powerful intention: otherwise the audience accurately read the performer’s real intention “to put my hand into the right place”. What is often missing from modern productions with ‘baroque gesture’ is the rich network of interconnections between gesture, music and text: audiences are therefore left unmoved by the emotions that should flow through those networked connections. What matters is not what you do with your hand, it’s what your hand “means to say”.

LANGUAGES OF EMOTIONS IN RECITATIVE

One particular result of my ‘Text, Rhythm, Action’ investigation within CHE’s Performance program has been to suggest a re-defining of Recitative, the musica recitativa of the first operas, not as ‘the boring bit in between the nice tunes’ but according to its literal meaning in Italian as “acted music”. (Read more here) In this new dramatic style, an innovation around the year 1600, the composer uses musical notation to recreate the dramatic timing, rhythmic patterns and pitch contours of theatrical speech. Peri explains how to do this:

I know similarly that in our speaking some tones are pitched in such a way that they could create music, and in the course of narration many other [tones] pass by, which are not pitched, until one returns to another [tone] suitable for movement of a new harmony …. And I made the Bass … according to the emotions, and kept it unmoving through the dissonances and through the correct consonances, until the tone of the speaker running through various notes, arrives at one which in ordinary speaking would be pitched, [this] opens the way to a new harmony;

Peri Preface to Euridice (1600)

This is just what we see in Monteverdi’s setting of in questo lieto e fortunato giorno.

Il Corago emphasises that singers should vary their tone-colour, so that recitative sounds just like the speech of a fine actor, which – as Shakespeare agrees – was learnt by rote: “Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to you”. Cavalieri and Il Corago emphasise variations in speech patterns, variations of pitch and syllabic lengths, just as we see in Cavalieri’s, Peri’s and Monteverdi’s notation of recitative. In Gibbons’ Cries of London, too, variety of pitch and syllable lengths in the persuasive calls of street sellers is contrasted with the dreary monotone of that 17th-century news-announcer, the Town Crier. Shakespeare similarly contrasts his ideal of declamation, speech rhythms that dance “trippingly on the tongue” – with the Town Cryer’s habit to ‘mouth it’.

But within this essentially aural tradition of acting, there were strong conventions allowing less freedom than one might expect in the delivery of a particular line:

In recitative… there is but one proper way of discoursing and giving the accents.

Samuel Pepys

Jacopo Peri, Samuel Pepys & the Town Crier

Perhaps you remember James Alexander Gordon reading the classified football results “The best way to do it is to get the inflection right. If Arsenal have lost, I’m sorry for them. If Manchester have won, I’m happy for them. So it would go something like this: Arsenal 1, Manchester United 2. And so on, and so forth.” (See a video interview with JAG here).

If baroque actors declaimed particular lines in a consistent manner, we should therefore expect corresponding consistency in 17th-century musical settings, and as part of my new CHE investigation into musical imagery, “Enargeia: Visions in Performance”, Katerina Antonenko and I have already begun to find supporting evidence.

For example, Monteverdi sets the word “Signor” with the same upward inflection, a rising minor third, as pronounced both by Poppea and (in Orfeo) by Proserpina. We can easily imagine that this follows a conventional speech pattern of courtly etiquette: “My Lord?” Signor?

It’s well known that the word sospiro (a sigh) is almost invariably associated with a short rest in the music. Less well known is that in 17th-century Italian, such short silences are not called pausa (this is the term for longer silences) but sospiro. Still less well-known is that 17th-century lovers sighed on the in-breath, Ah! not Ha! And Katerina has noticed that many sighs in Orfeo are associated with the same pitch, around low F#.

When for you (Ah!) I sighed

You (Ah!) sighed

crying (Ah!) and sighing

After a deep sigh (Ah!) she expired in my arms

Note the link between inspiring the breath of emotion as Orfeo sighs for love, and expiring the breath of life, as Euridice dies. This breath is Pneuma, the renaissance spirit of passion. It is very likely that 17th-century actors (and singers) sighed (on the in-breath) audibly at such moments, though this is seldom done today.

EXCLAMATIONS: EMOTIONS WITHOUT TEXT

Exclamations – Ah! Oh! – are pure emotion, essentially without text. Around the year 1600, the exclamatione was a novel vocal technique, following the fashion for more emotional delivery. Caccini gives three ways to start a phrase: intonazione, messa da voce and most up to date and emotional, exclamatione.

Consistently, Monteverdi sets exclamatione to medium-high notes, D or E.

Tancredi in Combattimento

Messaggiera in Orfeo

Orfeo (2 examples)

Euridice & Messaggiera

Orfeo (3 examples)

ALL from Orfeo

Another exclamation, ohime! frequently combines medium high pitch, around D, with a falling inflection, and dissonant harmony.

And Orfeo’s delivery of the word lasso (Alas, wretched me!) is similar to the Messagiera’s pronunciation of the feminine equivalent lassa.

Note that when several exclamations follow one another, the pitch of the note follows the rules of rhetoric, either building upwards, or (for three iterations) high, low, higher. The rhythm is syncopated, off the beat, showing that something is wrong. A bass-note from the continuo defines that beat…

Ohi… BASS-NOTE … me!

which might be reinforced by the actor changing his stance, even stamping his foot on that beat.

And pitch contour and rhythm combine perfectly with the appropriate gesture, throwing out the hand high, above the head for Ohi… and then returning it to the chest (perhaps even striking the chest audibly) at …me!

As Il Corago tells us, pitch contours communicate emotion very effectively. This is true even without words – think of mother/baby talk, or the BBC children’s series the Clangers, in which characters ‘spoke’ only with inflected whistling sounds, performed by leading comedic actors of the day, on swanee-whistles. (If you don’t know the Clangers, you can hear them here).

Quintilian agrees:

The second essential is variety of tone, and it is in this tone that delivery really consists… Take as an example the opening of Cicero’s magnificent speech… Is it not clear that the orator has to change his tone almost at every stop?

GESTURE: EMOTIONS WITHOUT WORDS

Bulwer and Bonifaccio consider gestures to be wordless expressions of emotion:

Gesture, whereby the body, instructed by Nature, can emphatically vent, and communicate a thought, and in the propriety of its utterance expresse the silent agitations of the mind

Bulwer

And in Elizabethan times there was a fashion for silent pantomime, or Dumb Show. [See Dieter Mehl The Elizabethan Dumb Show: The History of a Dramatic Convention (1965)]. Some of Bulwer’s gestures can be confusingly similar:

“Munero” I give money

“Demonstro non habere” I show I have nothing

And Elizabethan Dumb Shows were, if not inexplicable, certainly hard to understand. So after the pantomime, the actors might re-enter, whilst someone explains what it all had meant:

Sir John, once more bid your dumb-shows come in,

That, as they pass, I may explain them all.

Munday’s Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntington

So also in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, where after watching the Dumb Show, Ophelia asks: “What means this, my Lord”, and when the Prologue enters, she asks again: “Will he tell us what this show meant?”

SINFONIA: PICTURES WITHOUT TEXT

In Recitative, music imitates the declamatory rhythms and pitch-contours of dramatic speech. And in all kinds of music, composers used the technique of madrigalism to ‘paint the words’, so that the music creates a detailed sound-picture of the text. Ut pictura musica – music is like a picture. This extends even to instrumental music, labelled sinfonia or ritornello in early operas. Just as with spoken declamation, there were strong conventions at work.

One of the first conferences presented by CHE was on the Power of Music, which was a highly significant topic around the year 1600. Many of the early operas explore the Orpheus myth, in which the protagonist has the power to influence nature with his music (birds, animals even trees come to listen, stones weep), to persuade Hell, even to conquer death. This cosmic, super-natural, super-human power is related to the three-fold identity of Music as

- Musica Mondana – the Harmony of the Spheres, the perfect music created by the slow dance of the stars and planets

- Musica Humana – the harmonious nature of the human body

- Musica Instrumentalis – actual music, played or sung

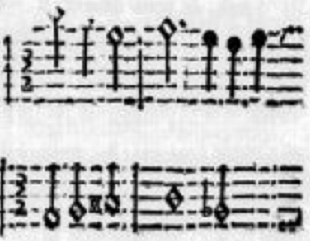

Many philosophical concepts are depicted in musical ‘paintings’ of the Power of Music. Orpheus’ lyre (or his father, Apollo’s) is represented by an ensemble of bowed strings. The stability of the cosmos is reflected in root-position chords and simple harmonies – corresponding to the fundamental mathematical ratios that structure music itself, and were believed to describe the circular orbits of heavenly bodies. The ‘universal string’ is tuned of course to Gamut, low G, the lowest note of renaissance music theory (even if in actual practice, lower notes were frequently used). The benevolence of heaven is heard in the gentler sounds of the Soft Hexachord, of B-molle, i.e. G minor. The perfect movement of the heavens is a slow, formal dance. And ascending and descending scales represent in music the mathematical relationships between one Sphere and the next.

Two of the most famous soundscapes of the Power of Music, Malvezzi’s Sinfonia representing the Music of the Spheres in the first of the Florentine Intermedi (1589), and Monteverdi’s Sinfonia representing the power of Orpheus’ lyre to persuade Hell (the same Sinfonia is heard again in the last Act, when Apollo descends from heaven to rescue Orfeo from despair), show all these features:

- string ensemble

- root-position chords

- G with a ‘key-signature’ of Bb

- pavan rhythm

- scales moving through the texture

UNITING THE LANGUAGES OF EMOTION

In spite of the possibilities of ambiguity in Dumb Shows, in Peindre et dire les passions (2007) Rouillé has convincingly used Gesture to identify the precise words, and hence the emotions, depicted in baroque paintings. She shows consistency of baroque Gesture between John Bulwer’s English diagrams and French paintings, e.g. the gesture for “Pay attention!”We can see similar matches between Bulwer’s English gestures and Bonifaccio’s Italian cenni, e.g. the sign to an audience for “Silence, I intend to speak”.

Musicologist Louise Stein has drawn attention to a strongly consistent dramatic style in Spanish theatrical laments. The heroine (such laments are always given to a female role, even though male roles were also acted by female actors) exclaiming on high notes, calls upon all nature to rescue her, and dividing the entire cosmos into related sets:

Sovereign spheres, powerful gods; heaven, sun, moon, stars; rivers, streams, seas; mountains, peaks, cliffs; trees, flowers, plants; birds, fish and beasts; sympathise with me, have mercy on me… air, water, fire and earth!

Calderón/Hidalgo Celos aun del aire matan (1660)

We are currently working on a Russian translation of Celos for a production in Moscow, and with recent CHE findings fresh in my mind, I suddenly realised one more reason why this model of lament would be emotionally effective on stage – the conventions call for actors to point at what they speak about. So the actress exclaims and laments with many thrilling high notes and dramatic changes of register as the music ‘paints the words’, and simultaneously her gestures are equally powerful: hands sometimes raised high above the head, then swept dramatically downwards. Spanish Laments represent visual as well as musical exclamations.

The only practical difficulty is that a few lines earlier, the goddess Diana (who is about to execute our heroine) has commanded: “Tie her to a tree trunk, with her hands behind her”. This would prevent the actress from gesturing at all. But as the Lament begins, the command has not yet been executed, as the Text reveals: “Tie her up, what are you waiting for”. As any theatre producer knows, the spoken (or sung) text provides many details of Stage Directions.

This convention, that actors point at what they speak about, extends to poetic imagery which might be realised in stage scenery, or simply imagined by the actor. “To the hills and the vales, to the rocks and the mountains, to the musical groves, and the cool shady fountains” sing the Chorus in Purcell’s Dido & Aeneas. Singers would point out each feature, whether it is actually visible in the theatre or not, so that the audience ‘see it’, either in the ‘reality’ represented on stage or imagined, in the mind’s eye. In many early operas, poetic imagery in the libretto matches the real-life surroundings of the theatre, so that actors point outwards towards what they imagine, and the audience already knows, is actually there, outside in the real world.

BACK & FORTH

If we accept that Action and Music have at least some characteristics of language, then meaning must flow not only from, but also back to, the performed Text. ‘Suit the Action to the Word, and the Word to the Action.’ Meaning also flows to and fro between Music and Action, Music and Text.

Historically Informed performers usually work from the Text and seek to move the passions of their audiences. At first glance, problematising the language of historical Emotions threatens to saw off the branch we are sitting on. If we question the meanings of historical words of emotion, how can we understand the music attached to those word? But given the reversible flow of meaning between Text and Performance, perhaps Music and Action can contribute to the linguistic debate.

FROM MUSIC BACK TO TEXT AND PASSION

In early music, well-understood historical principles of harmony (dissonance/resolution) and melody (hard/soft hexachords) allow us to assess objectively the intensity and character of an affective turn of phrase. If such an accento can be consistently linked to a passionate Word, we can reach a better understanding of that Word’s Emotional significance.

B natural, any sharps, and harmonies on the sharp side are associated with the Hard Hexachord, and therefore with hard emotions – dry Humours, Melancholic or Choleric. B flat, any flats, and harmonies on the flat side are associated with the Soft Hexachord, and therefore with soft emotions – wet Humours, Sanguine or Phlegmatic. So in his (Italian) Lament, Orfeo alternates between sadness in soft G minor and anger in hard A major. The most acute contrast of opposites comes at the words “on my troubles have pity”, moving from hard G# on mal to soft Bb on pietate, with an unsettling chromatic twist that matches the turn of the emotional screw.

Investigation of musical emotions in standard repertoire has sometimes focussed on moments of particular intensity, thrilling, spine-chilling moments, the ‘tingle factor’. We have informally collected audience reports of such moments in early opera, and many of them are linked to a particular turn of harmony towards the soft hexachord. This corresponds to an emotional truism, that it’s not the hardest moments that make you cry, but the moment when amidst the toughness, you are offered a hint of sympathy. It’s the easing of the emotional pressure, the change of affetto, the move to the wet Humour that allows the tears to flow.

Particularly strong examples we’ve observed in 36 performances so far of Anima & Corpo are Anima’s last words (moving from hard G major to soft C minor), and the chorus at Corpo’s final exit (the body ages and dies, even though the soul is eternal), which moves even further from hard A major to the same soft C minor. This moment regularly reduces audiences and many of the company too to tears.

canti la lingua e le risponda il core

At this moment of emotion, the meaning of the words (shown here in the Russian edition and original Italian) is highly significant: “the tongue sings, and the heart responds”.

Another tear-jerker is the final scene of Monteverdi’s Combattimento: Clorinda’s dying words move from hard E major to soft D minor. “Heaven opens, I go… -that’s the moment – in peace”.

![Heaven opens I go [in peace]](https://andrewlawrenceking.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/sapre-il-ciel.png?w=440)

Heaven opens, I go

[in peace]

At the conclusion of the CHE-supported performance in London there was a very extended silence, broken only by the sound of an audience member crying.

Musicologists have a good understanding of the relative intensity of particular harmonies, according to 17th-century conventions. So as we look at the harmonies a composer assigns to particular words of the text, we have a reliable impression of the emotional intensity, moment by moment, word by word. Analysing the harmonies of Cesare Morelli’s setting for Samuel Pepys of To be or not to be on a simple scale of 1-5 allows us to chart the emotional intensity during this famous speech. Morelli’s setting is thought to have been inspired by the declamation of Thomas Betterton.

Whilst it would be unrealistic to expect a perfect mapping of meaning, or even the kind of translations we can make between say Italian and English ,the transforming ‘languages’ of historically informed Performance might help shape a modern understanding of the Emotional Meaning of historical Words.

In future investigations, it would be interesting to study contrafacta, where a new text is set to existing music. What are the emotional parallels between the original and new texts? How do these ‘emotional synonyms’ translate the music’s language of emotion?

FROM GESTURE BACK TO PASSION

Gesture is both cause and result of emotion, creating a spiral of intensity.

These motions of the body cannot be done, unlesse the inward motions of the mind precede,

the same thing again being made externally visible,

that interiour invisible which caused them is increased,

and by this the affection of the heart, which preceded as the cause before the effect…. doth increase.

Bulwer

Gestures are preceded by emotion, and make that emotion outwardly visible. But that physical movement then increases the inward emotion. Modern scientific studies support the traditional belief of actors that Emotions work not only from inside outwards, from the performer’s intention to exterior display, but also ‘from outside inwards’. Paul Ekman has shown that accurately reproducing the changes in facial musculature associated with a particular emotion calls up that very emotion, without any other stimulus. If the hypothesis of ‘mirror neurons’ is believed, then here is a mechanism that might explains one mode by which audiences themselves feel the same emotions portrayed by the performers they are watching.

At a recent workshop on the Feldenkrais Method, I witnessed a very telling demonstration that physical processes (in this case, the precise position of one particular neck vertebra), vocal production and emotion are closely intertwined. After the therapist had showed the singer how to reposition her head over her spine, she sang again the song she had sung moments before: the sound was utterly different. The singer was shocked, re-started, and then burst into tears. The voice was resonating freely, the emotions were flowing freely. And an audience member commented that the phrase sung after physical repositioning also communicated more emotion to listeners.

All of this fits perfectly with the renaissance theory of Pneuma, which links the mysterious Spirit of Passion (communicating emotion from performer to audience) with a flow of mystic energy in the body (rather like Oriental Chi) that promotes proprioception and relaxed movement. The same Pneuma is also associated with the divine energy of creation, the breath of life itself. The three-fold nature of Pneuma parallels the three kinds of Music.

We might therefore experiment with using historically informed Action, suited to a period Word, to re-create physical sensations, to re-embody and (in some way) ‘experience’ a historical Emotion.

DICTIONARIES OF LANGUAGES OF EMOTION

This brings me to the idea of Emotional Dictionaries, charts of Meanings between one discipline to another, an idea that regularly emerges in CHE discussions. For Historically Informed Performance, I think we need to compile dictionaries that function in the opposite direction to the historical sources: not from Gesture to Word (as Bulwer and Bonifaccio inform us), but from Word, or better still, from Passion to Gesture. This is the approach I’ve taken in my work-in-progress guide to Historical Action, which we continue to test and develop in CHE performance projects around the word.

Cross-connection dictionaries would be interesting too: from Gesture to Harmony, from Scenery to Heaxchord, and (for instrumentalists) from Music to Words. As you will remember, high D- low F# means “Ohime!”.

CONCLUSION

Below the tip of the Text iceberg lies the emotional subtext – this is what really concerns performers and – even more importantly – their audiences. It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it. It’s not the notated words and notes, but how you deliver them, with posture, gesture, and with variety of vocal colour. It’s not about where you put your hand, it’s what you mean to say with your gesture. It’s not about the sound, it’s about the pictures. It’s not about singing at the audience, but about telling them a story.

It’s about uniting and synchronising all the languages of emotion, putting Text and Music into Action. As Bulwer writes, quoting Quintilian quoting Cicero quoting Demosthenes:

What are the three secrets of great delivery?

Action, Action, Action!

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our website www.TheHarpConsort.com .

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago, and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions.

![Heaven opens I go [in peace]](https://andrewlawrenceking.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/sapre-il-ciel.png?w=440)