What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet.

Shakespeare Romeo and Juliet (1597) Act II Scene ii

The Shakespeare Rose

This is the first in a series of posts reporting on the recent Music & Consciousness 2 Conference at Oxford University. Here I present the first part of my own paper. The second part and discussion of other papers will appear in subsequent posts.

Flow, an optimal state for study, training and creativity, is often linked with the concept of The Zone, an ideal state for elite performance. Are these two states identical, or how might they differ? Does it matter, which name we use? See more at TheFlow.Zone

See also May the Flow be with you! here.

ABSTRACT

In this first of two parts, I’m considering the similarities between Flow and The Zone, as two of the many different manifestations of Hypnotic trance. I’m arguing for very careful use of language, but not for the sake of a more rigorous theoretical discussion. The narrow definitions of some terms are highly contentious, so I’m deliberately accepting broad definitions in order to sidestep those theoretical debates. But I suggest that precise choice of terminology is vital, for utterly practical reasons.

As you read this paper, imagine it being presented aloud at a conference, with the words in bold emphasised by subtle changes in vocal tone.

APPROACH

My approach to this subject is Experiential, Phenomenological, individual and practical. I draw on my personal experiences as an international musician, as a professionally qualified sailor (sailing is one of Csikszentmihalyi’s favourite examples of Flow) and as an elementary student of Feldenkrais Method, Tai Chi, modern Epée and historical Rapier. I’m also privileged with many opportunities to compare notes with fellow performers and advanced music students, as well as with highly experienced teachers and some of the world’s most insightful sports trainers and martial artists. The theoretical background to my approach is Joe Griffin’s Expectation Theory of Dreams. Griffin speaks about his theory on video:

I discuss the implications of Griffin’s theory for Flow and for music & drama here.

STATES

For a moment, let’s leave aside the much-debated theoretical question of whether or not Flow can strictly be termed an Altered State of Consciousness, although later I’m going to place great importance on nomenclature for practical reasons. We can agree, can’t we, that sometimes we feel in the mood to work, ready to practise; or we feel the coffee-break coming on, or even “I’m in a right state”; or we experience that je-ne-sais-quoi as we walk out on stage in front of a packed auditorium, or line-up to compete in a major sports event.

Our expectations and habits, our deliberate preparation and conditioned reflexes, Anchors in NLP-speak, set up mind/body responses which can be positive or negative for desired outcomes in specific situations. Those responses can be optimised through mental and physical training: music lessons, practising and rehearsals; sports training and coaching sessions.

LANGUAGE

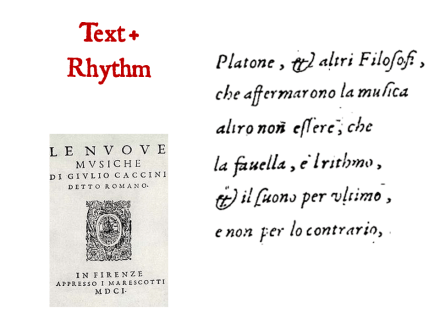

Those responses are most effectively optimised through combined mind/body training in which physical processes and neural changes are programmed by specific use of language.

It matters – a lot – what you say in a music-lesson, rehearsal or coaching session. It matters – perhaps even more – what you say to yourself, your inner dialogue, whilst practising. My choice of words as director differs depending on whether I’m rehearsing baroque specialists or a modern chamber orchestra. And each individual has their own inner dialogue and primary sensory modality. “I see what you mean.” (Visual). “I hear what you’re saying.” (Auditory) “I’ve got a hold on that idea.” (Kinaesthetic) “That feels right.” (Somatic) “Sweet!” (Gustatory).

ASSUMPTIONS

I began my research with two huge assumptions. I won’t call them hypotheses, because they probably can’t be proved. It may well even be impossible to falsify them. But thus far, they are producing meaningful questions and plausible answers.

My first assumption is that this phenomenon of Flow has some essential common features across a wide range of activities: study, creative work, music-making, sports, martial arts, flying aeroplanes etc. Csikszentmihalyi has observed the outward signs of Flow in many different situations, but it remains an unproven assumption that the inner reality is somehow ‘the same’.

The second assumption is that Flow is an ‘altered state of consciousness’ similar to ‘hypnosis’. Just as there is debate about the notion of ‘altered states of consciousness’, there is no universal agreement about what Hypnosis is. The ‘first and perhaps most important’ theme of ‘dialogue and debate’ in the 2008 Oxford Handbook of Hypnosis is of definition: what is Hypnosis? However, the neural correlates of Hypnosis have been identified:

‘Now, numerous experimentally controlled investigations have produced consistent and converging findings demonstrating physiological responses associated with hypnotic conditions … these markers directly reflect the alterations in consciousness that correspond to participant’s subjective experiences of perceptual alteration’ [Barabasz and Watkins 2005].

What is Flow?

HYPNOSIS

Whilst there are many unanswered questions in Hypnosis Research, linking Flow to Hypnosis invites us to consider all the work that has already been done for Hypnosis for possible relevance to Flow. For example, neurological patterns whilst hallucinating a certain action in Hypnosis closely resemble the patterns for that activity when carried out for real. Similarly, we can expect that the brain activity of a musician playing in Flow will resemble that of another musician not in Flow, more than that of Flowing Kung Fu fighter. Any specific neurological markers for Flow are likely to be subtle, but Hypnosis studies might suggest where to look. [There were tentative suggestions of neural correlates for Flow in other papers at the Oxford Conference].

Researchers tend to adopt a narrow definition of Hypnosis, requiring a formal induction and specified tests. Experimental work begins by testing subjects for hypnotisability, using a Standardised Induction. Most practitioners work with a broad definition, using a great variety of inductions, formal and informal. The guru of modern hypnotism was Milton H Erikson, who viewed trance as a natural phenomenon, a state we all go in and out of several times a day.

What is Hypnosis?

Have you ever made a familiar journey, and found yourself at your destination with no clear memory of how you got there, because your mind was on something else? You were in a travel trance. Have you ever been in a lecture-room and found yourself off in a little daydream, with no idea what the speaker just said? You were in a conference trance!

Erikson’s mantra was to Accept and Utilise his clients’ reactions. So if you have already drifted off, wonderful! I can get my suggestions over so much more effectively, if you are in trance. Erikson’s approach was client-centred, tailored to each individual, whereas Research pre-supposes that the Hypnotist has his own agenda. There are ethical considerations here. In the Eriksonian understanding of Hypnosis, self-hypnosis is quite possible, and most practioners consider it highly beneficial, teach it, and give Suggestions during sessions of guided hypnosis to facilitate self-hypnosis later.

What is NLP?

Neuro-Linguistic Programming largely derives from Eriksonian Hypnosis, analysing precise use of language to maximise the speed and efficacy of Suggestions. NLP is ‘take no prisoners’ Hypnosis: it does not beat about the bush, but cuts straight to the chase. Consequently, before embarking on any therapeutic procedures, NLP practitioners spend some time establishing whether the client really wants and is ready for the requested change.

Practitioners recognise that individuals respond to Hypnotism in different ways, and that an Induction that works for one person may not work for another. In the Eriksonian approach, the Hypnotist does not try to force through against ‘client resistance’. Rather, one accepts that a certain Induction or Suggestion isn’t working, and one tries to utilise that knowledge to indicate a more promising alternative.

In my favourite Erikson story , the famous therapist was struggling with a difficult case: he couldn’t find an effective therapeutic approach. So he hypnotised the client, and brought him (whilst in trance) forwards in time to a date after the successful conclusion of his treatment. He then asked him what the therapy was, that had succeeded, and having obtained the answer directed the still hypnotised client to forget this conversation. He then brought the client back to the present, re-oriented him out of trance, and applied the therapy as described. It worked a treat.

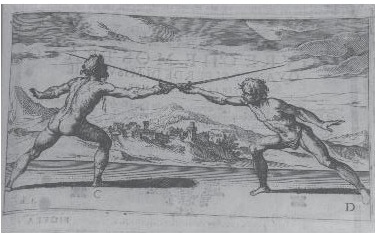

The point is that the unconscious mind is a rich resource, full of knowledge and skills that may not be available to us in normal consciousness. In music teaching and sports coaching, the 19th and 20th-century trend was towards analysis and scientific teaching of step by step processes. But sometimes it can be more effective to reverse-engineer: focus on the end-result, and let the student’s unconscious figure out the required process. Fencers are taught to imagine the target attracting the point of the sword towards it.

HYPNOTISABILITY?

In principle, NLP does not accept the concept of hypnotisability. If your client cannot be hypnotised, you are using the wrong induction. Conversely, many people enter Hypnosis without formal induction. If this is true, as most practitioners believe, then some of the most rigorous Hypnosis Research is called into question. Standard practice compares the responses to Suggestions of hypnotised subjects and of a control group who did not receive an Induction and are therefore taken to be in a normal state of consciousness. But in the NLP view, there is no guarantee that the control group are not also in trance, especially if you start making hypnotic Suggestions to them. Indeed, in NLP, the very concept of ‘normal consciousness’ is questioned.

FAQs

One of the most inspiring applications of Hypnosis is for control of pain during surgery, for example for patients who are are allergic to conventional anaesthetics. I’m acquainted with a Hypnotist who provides hypnotic anaesthesia for major dental surgery – if anyone still thinks of Hypnotism as a party-trick or a new-age fad, this clinical application is undeniably the real thing. Some clinical psychotherapists use Hypnotism alongside other talking therapies.

Then there is a huge Hypnotism industry worldwide, offering Hypnosis in face-to-face sessions, on CDs and DVDs, or for download from the internet. Help with losing weight, giving up smoking, relationship problems, phobias and anxiety is much in demand. Alongside these, and also in sports- and music-guru websites, Flow and other performance-enhancing concepts are marketed similarly. In these circles, it is taken for granted that Flow or ‘being in the Zone’ is the secret of elite performance, and that Hypnotism can help you achieve it. The most frequently asked questions are How can I get into Flow? How can I keep Flowing in difficult circumstances? How can I cope with Performance Anxiety?

Flow FAQs

Griffin’s theory of Dreams offers an explanation for the link, often remarked on, between high creativity and susceptibility to mental illness. Recent studies have highlighted the incidence of mental health problems and alcohol dependency amongst professional musicians; performance anxiety afflicts not only students but many established performers. Beta-blockers and other drugs are frequently needed, to say nothing of dangerous levels of caffeine. Mental illness causes untold suffering not only to the patient, but to their families and to society as a whole: the recent airplane crash in the Alps is tragic example. See Griffin & Tyrell How to lift Depression […fast] here.

Many people find that trance itself – for example, in Meditation – is a beneficial experience, even without any deliberate input of therapeutic Suggestions. Flow for music-making, for study, creativity and for life in general, is highly conducive to mental health.

HOW CAN I GET INTO FLOW?

Csikszentmihalyi associated Flow with a particular personality type, the Autotelic, from auto ~ self & telos ~ purpose. Autotelics are strongly self-motivated, ready to do something for its own sake, ‘because it’s there’. If you feel that the task at hand is interesting and worth doing, you are more likely to be in Flow whilst you are doing it. If you can find this motivation for yourself in many activities, you can live much of your life in Flow.

This is all very well, but it does not answer the most frequently asked question: How can I get into Flow, now? Re-building your entire personality might be a long-term project. Can we find a short-cut, a magic portal, a hidden gateway into Flow?

How can I get into Flow?

The idea I’m putting forward here, that Flow might simply be a phenomenon of Self-Hypnosis, seems to be a new contribution to the field. The implication is that techniques for entering Flow would resemble hypnotic Inductions.

TYPICAL HYPNOSIS SESSION

Hypnosis 1: Pre-talk

So let’s look at a typical experience for a Client who visits a modern Hypnotist. There will be some introductory chat, which the experienced Hypnotist will utilise to build rapport, to find out what’s important to his Client, to explain the procedures of the session and to instill confidence. This phase is called the Pre-Talk, and a fine Hypnotist will be able to do a lot of effective work, before taking the Client into trance. An NLP practitioner might not draw any hard boundary between pre-talk and trance, regarding shifts of state as a natural process that is happening anyway.

Hypnosis 2: Induction

There are many possible approaches to Induction (for example, there’s a list of over 30 different Inductions here), but most of them mimic the results of Hypnosis, slow deep breathing, fluttering eyelids, etc. so that the unconscious mind reverse-engineers trance as a cause. Suggestions for relaxation and concentration, whilst seeking an inner focus, are very often employed, using a gentle tone of voice… drifting easily from one suggestion to the next … smoothly avoiding full stops … timing suggestions with the Client’s outbreath…

Alternatively, one can overload the conscious mind with shock, excessively confusing language, or too many simultaneous demands, so that the unconscious is forced to step into the gap. Fencing coaches deliberately employ such Stack Overload, maintaining the complexity of swordplay just beyond the pupil’s comfort zone, in order to keep the unconscious mind positively engaged whilst under the stress of combat.

Ericksonian Hypnotists use the mnemonic SOLER for techniques that facilitate rapport:

Erikson’s SOLER mnemonic

- Sit (be comfortable, and on the same level with your client)

- Have an Open posture

- Lean forwards (and concentrate closely on the client)

- Make Eye contact

- Relax

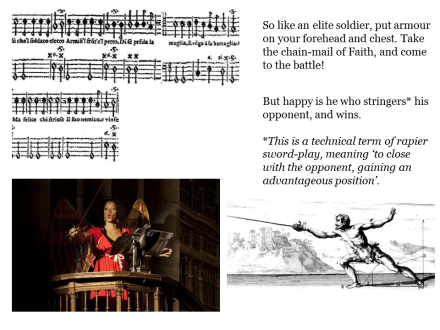

With such rapport, and with the Hypnotist also enjoined to sit comfortably, concentrate and relax, it is hardly surprising that one can all too easily end up hypotising oneself. In the NLP view, mutual trance is inevitable and no bad thing: Hypnotist and Client find themselves in complementary states of consciousness, similar but not identical. So too performers and audiences: see The Theatre of Dreams: La Musica hypnotises the Heroes here.

Neuro-Linguistic Programming

NLP practitioners use indirect language, so-called Sleight of Mouth, to smuggle suggestions past the conscious mind in order to influence the unconscious. Conjunctions – as, while – can link a truism to a desired response: As you breathe out, you can feel your shoulders relaxing. Whilst you sit in this room, you’re unconscious mind can access new learnings. Clearly, you are sitting in this room and breathing; the implication is that the second half of each sentence is also true. Emphasising certain words allows the Hypnotist to hide an Embedded Command within an apparently innocuous statement: “your Unconscious” sounds like “you’re unconscious”. Deliberately vague language, Nominalisations in NLP-speak, access new learnings rather than learn something new directs the mind inwards in the search for meaning (a Trans-Derivational Search).

Whilst you sit in this room, you’re unconscious mind can access new learnings.

So it’s no wonder that the abstract, nominalisation-rich language of academia puts people to sleep!

There are many, many more NLP techniques, subtle use of language that works directly on your Unconscious mind, to get the results you want. Read more here.

Hypnosis 3: Suggestion

With the Client in trance, there may be a two-way conversation, or the Hypnotist may ask for non-verbal responses – raise your hand when you’re ready to continue . Typically, the Hypnotist gives Suggestions for desired responses to specific situations in the future. As you walk out on stage, and you take a deep breath, you will feel your shoulders relax, and your whole body feels warm and relaxed. with a pleasant sensation of calm confidence. Suggestions work without trance, especially if you use NLP techniques to aim the Suggestion direct at the Unconscious mind. But Suggestions work better with trance, and best of all with a combination of trance and NLP’s clever use of language.

And of course, your own internal dialogue, the way you talk to yourself (perhaps mostly imagined, sometimes out loud) is a powerful form of Suggestion. It’s worth becoming aware of this ‘self-talk’, and learning to direct it the way you choose to. If your internal dialogue is over-critical, negative and in a harsh tone of voice, you are are imparting powerful negative Suggestions at point-blank range. Adjust the tone-settings, and re-record the announcements with a new script, so that you speak to yourself with gentle encouragement, some firm guidance to follow your chosen path, whatever would help you most. Your internal dialogue is like having a personal trainer whispering in your ear 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Make sure this “personal trainer” shares your agenda and speaks to you with warm encouragement.

Most people can take charge of their internal dialogue, and improve its quality, with a bit of work. But if you realise that your self-talk is highly negative, and you are unable to change it yourself, then seek help. An NLP or hypno-therapist can fix this for you, easily and quickly. I would recommend a therapist using the Human Givens approach, see here.

A wily Hypnotist will Suggest that next time, the Client will find it easier and quicker to go into trance.

Hypnosis 4: Re-orientation

Then the Client is gently re-oriented back to normal consciousness: the classic procedure is a 3, 2, 1 countdown, Suggesting a pleasant experience as you emerge from trance.

Learning as a post-hypnotic process

If we now look at a sports coaching session, there are obvious similarities. In the pre-talk, the team are brought together, rapport is established, the program for the session is announced, the vocabulary shifts from everyday to specifics. Warm-up exercises aim for a certain combination of concentration and relaxation, there may even be a formal ritual for achieving the desired state of mind and body (e.g. the New Zealand ruby team’s Haka). With the athletes in the Zone, the coach gives Suggestions to improve performance. The session ends with a warm-down, and a good coach sends everyone home feeling good.

Sports Coaching compared to Hypnosis

Similarly, a typical music lesson begins with a pre-talk which establishes rapport, eases the student from everyday life into a suitable state of mind for high-level music-making. A good teacher will calm an agitated student, energise one who is lethargic, and try to find out how best to fit the lesson to the student’s current needs. Many lessons begin with exercises for relaxation, physical and mental ‘centering’, almost a formal ritual for entering the desired state. During the lesson, the teacher offers Suggestions to improve technical execution, or to help the student engage more fully in musical emotions. Finally, the teacher makes Suggestions for the forthcoming performance, and/or for the next week’s practising, and re-orients the student back into everyday life with some concluding chat.

Music Lesson compared to Hypnosis

The working definition of Hypnosis put forward by Kihlstrom fits Music rather well.

Definition: is this Music, Sports-coaching, or Hypnosis?

A process in which one person … offers Suggestions to another … for imaginative experiences entailing alterations in perception, memory and action. In the classic case, these experiences are associated with a degree of subjective conviction…and an experienced involuntariness…As such, the phenomena … reflect alterations in consciousness that take place in the context of a social interaction.

Of course, a good teacher will offer Suggestions for imaginative experiences, and will try to improve the student’s perception, memory and action. Good musicians develop a ‘feel’ for the music, a strong sense of subjective conviction:

When I played through the whole piece, it just seemed that this passage had to be loud.

And when you are playing especially well, you can ‘let your fingers do the hard work’:

If you just close your eyes, relax, and focus your intention on that octave leap, your fingers will find their way to the right note all by themselves.

Music and sports coaching closely resemble hypnosis sessions, especially if they are done well. If there is good rapport, good concentration and the right kind of relaxation, good coaching takes both participants into a special state, in which there is communication and learning via the unconscious mind, facilitating powerful Suggestions for future action.

Mind/Body Awareness

Many music conservatoires offer classes in Mindfulness, Yoga, Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais Method. Tai Chi and other disciplines teaching mind/body awareness. These are highly effective in improving concentration and relaxation, and instilling an effortless way to use the body that gradually becomes ‘second nature’, ‘automatic’. These outcomes help students enter the music-making trance more easily, and the teaching methods are also highly hypnotic.

Mindfulness teaches breathing exercises and control of one’s own attention, for example by intense focus on small movements. Feldenkrais directs the mind inwards with such questions as As you rest your feet on the floor, can you feel more weight on your right foot, or on your left? Or are they the same? Don’t change anything, just notice. This is a well-known technique of hypnotic induction. Feldenkrais also normalises and accepts the student’s experiences, in a similar way to Eriksonian hypnosis: ‘that’s right‘, ‘good‘. Making small changes to habitual actions calls the unconscious mind to attention:

Clasp your hands and interlace your fingers, then re-clasp them with the other hand on top … very good.

Similarly, Tai Chi and other martial arts use breathing, visualisation exercises, unfamiliar postures and exotic names – Nominalisations – to alter the state of consciousness of the student, in order to maximise the mind/body effectiveness of training. Stand in Wuji stance, with the head suspended from above, hollow the chest, relax the waist, open the Bubbling Spring points at the centre of each foot, let your hands rise of their own volition to hold a ball of green energy at eye level, breathe slowly, feel the Chi descend to the Dan-Tien.

This makes a perfect hypnotic induction, and the best teachers use a gentle, slow tone of voice, and linking conjunctions as recommended in NLP. AS you transfer the weight to the front foot … your right hand moves outward … PENG! See Michael Gilman’s Tai Chi videos, here.

But it’s not all gentle meditation. There is also inner power, the strength of spirit that we look for from a great musician or a dedicated athlete. Good martial arts require that same combination of relaxation and concentration that is induced in hypnosis. See Ian Sinclair’s approach to the Wuji Stance, perfectly characterised by his motto “Relax Harder”, here.

As all good teachers do, Sinclair uses humour to get across some of his most serious advice. A corny joke makes the lesson more memorable, of course, but it is also a NLP technique for disarming the conscious mind, so that the Suggestion goes direct to your Unconscious mind, where it is even more effective.

There are further connections here. Moshe Feldenkrais was himself a Judo black belt, and one of the first to bring Judo to the West. He contributed several books on Judo, which emphasise the deeper elements on the art, offering mental and spiritual development as well as physical skills. His first book on his Method for teaching Awareness through Movement links Body and Mature Behavior: A Study of Anxiety, Sex, Gravitation and Learning.

Hypnosis-aided Learning

One of the particular benefits of hypnosis-aided learning is that your Unconscious is given more opportunity to integrate newly acquired skills and knowledge with previous expertise. Relaxation, combined with enhanced access to the unconscious mind, promotes the establishing of new neural connections, and even allows the brain itself to grow, increasing neural capacity for the skill being practised – neural plasticity. Concentration encourages the growth of myelin around those neurones, leading to faster, surer responses.

ETHICS

If the NLP view (shared by many practising Hypnotists and Psychologists in this field) that trance is natural event is accepted, if we even admit the possibility that teaching can be a hypnotic process, then we should consider seriously questions of Ethics. If I’m giving a harp lesson, informed consent to Hypnosis has not been given. Nevertheless, good teaching should change the student’s state and help them access deep levels of the mind-body link. I would argue that good teaching cannot help but be hypnotic. So how can we ethically employ NLP techniques in teaching?

My personal response to this question of ethics could be described as “What does it say on the tin?”. If someone comes for a harp-lesson, I teach them harp-playing. If I’m asked for a lesson on Flow, or on Hypnosis, I’ll work on those topics. If someone comes for a harp-lesson, but it emerges that direct work on finding Flow or managing Performance Anxiety is needed, then I’ll seek agreement before changing the approach of the lesson. I introduce Feldenkrais Method in the same terms of “Awareness through Movement” that are standard vocabulary amongst Feldenkrais practitioners, using pre-recorded lessons prepared by licensed teachers. (I am not myself qualified as a Feldenkrais teacher. More about Feldenkrais Method here)

The Bottles Exercise

But here is an example of a ‘straight’ teaching technique that works by appealing to the student’s unconscious mind. I use this exercise to teach relaxation of the hands for Early Harp playing and also for Baroque Gesture.

1. Hold you hands out, palm upwards, and imagine that you are holding two large, 1-litre, plastic bottles, full of water. As the bottles lie horizontally in your hands, wrap your fingers gently around the bottles. Feel the cool touch of the plastic… are there drops of water on it? Use just enough strength to support the bottles.

2. Now pour out half of the water, and then hold the bottles again. Notice how much less effort is needed, now.

3. Now pour out the rest of the water, and hold just the empty bottles. Notice how your hands feel, now.

[Read more about applications of this Bottles Exercise for Early Harps and Baroque Gesture here]

Whenever I use the bottles exercise in routine teaching, I’ll explain that doing it imaginatively, without the actual bottles, is actually more effective, because it requires more concentration and engages the unconscious mind. I’ll use the vocabulary of concentration, relaxation, conscious attention and unconscious mind; but in a regular lesson, I would avoid the word Hypnosis.

How to Practise

I might explain how to practise an ornament slowly, with conscious attention, and then to relax, let go, and let your fingers fly ‘by themselves’. To help the student get the notion of conscious control and fingers that work ‘by themselves’, I often use the image of a little bird learning to fly, closely watched by its attentive parents. At a certain point, the bird just has to jump out of the nest and fly by itself. I help the student change back and forth between conscious control and ‘flying’, by teaching how to change the head-position and gaze, how to use breathing and posture. Sometimes it can help to distract the student’s conscious mind at the moment of ‘take-off’. See How to Practise here.

Baby Owl learning to fly

The interlinked themes of artistic intention, strength of purpose, emotional commitment, physical movement and emotional communication often emerge in music lessons. One needs a vocabulary for discussions of that emotional sensation of a dissonance, that is understood in the mind, felt in the body and mysteriously communicated to the listener; or for analysing the communication of musical effects that cannot actually be created on certain instruments. When you pluck a harp string, the sound then decays, you can’t make a crescendo. But I have to teach students how to make an audience believe there was a crescendo. Although there are technical tricks with sound-quality, timing, articulation and the dynamic relationship to preceding and following notes, the most effective strategy is to imagine the desired crescendo, as vividly as you can, and project that idea with all the force of your powers of imagination.

Similarly, in the Prologue to Henry V, Shakespeare asks the audience to work with their imaginary forces and to Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them / Printing their proud hoofs i’ th’ receiving earth. This entire speech, with its famous opening line O, for a Muse of fire, is a hypnotic induction that entrances the audience, encouraging them to suspend their (conscious) disbelief, to allow the actors to Suggest with their words far more than could ever actually appear on stage, and to receive those words into their Unconscious, in order to heighten their emotional response to the drama that follows.

Imaginary Puissance

NLP recognises that each individual has their own way of seeing the world, a preferred mode of representation. Erikson was always ready to change his vocabulary to suit his clients’ needs.

I vary my vocabulary, according to the student’s background. One can be scientific, and talk about intention and imagination; arty, with talk of magic and mystery; historical, with the 17th-century concept of Pneuma. Some students appreciate the computer-analogy; you sit at the keyboard, loading sub-routines into the computer, and then you hit RUN and leave the machine to operate at maximum efficiency without further keyboard input. Hungarian Flow-researcher Lazlo Stacho employs the vocabulary of Magic, recalling ancient connections between music and shamanism; there are still folk practices of hypnotism in Eastern Europe today. I find the Stars Wars idea of The Force helps some students find their own way to an understanding of these unconscious processes, that are hard to describe or measure.

Choice of vocabulary affects not only the processes of building rapport and trance induction but also the post-hypnotic end-result. In experiments on the use of Hypnosis for pain reduction, some Subjects were given the Suggestion You will not feel any pain; others were told You will notice the sensation of pain but it will not trouble you. Both Suggestions were effective, but Subjects described the results differently, and neurological measurements showed corresponding activation of different areas of the brain. The unconscious mind is capable of distinguishing between subtly different means of controlling physiological phenomena that are beyond our conscious control.

For this reason, whilst in theoretical discussion I adopt broad definitions of such technical terms as Hypnosis, Altered States of Conscious, Trance, Flow etc., I believe that in practical sessions one should take enormous care with the choice of particular words. It’s vital that teachers adapt their vocabulary to suit their students. In the spirit of Erikson’s Accept and Utilise, one should acknowledge the student’s viewpoint of these topics, and use the corresponding vocabulary. It may be effective to introduce some mysterious word, such as Oriental Chi or historical Pneuma, which can function as a Nominalisation and facilitate access to the Unconscious. But for teaching purposes, there is nothing to be gained by insisting on your own preferred vocabulary, your model of the whole process, even if (academically or scientifically) it is more correct. In this situation, your aim is to help students find (via the Unconscious mind) their own way into the desired state (whatever they want to call it, however they believe it works), not to engage their conscious minds in a debate over what the best name and most scientific explanation for that state might be.

Choice of Vocabulary matters for practical, not theoretical, reasons.

Chunking and Dissociation

One essential part of the learning process is chunking. For a beginner, playing a single note on baroque harp is a challenge: rest your hand on the harp with the fingers gently curved, relax the elbow, align the structure of your whole body behind and underneath your fingers, place your thumb on (not behind) the string, move your thumb slowly into the hollow of your hand allowing it to slip over the string whilst applying steady firm pressure, keep moving your thumb for the duration of the note. With practice, all of that is chunked-up into “Play a Good note”.

A sequence of Good and Bad notes (Good/Bad is a technical concept in Early Music, derived from accented and unaccented syllables in poetry: read more here) is chunked into a phrase. Phrases are chunked into sections, movements, pieces, entire programs. Effective performance depends on the unconscious mind doing the detailed work inside each chunk, whilst the conscious attention is at a higher-chunked level. You think about the phrase, your fingers play the notes ‘by themselves’.

In Hypnosis studies, this is a phenomenon of Dissociation: the conscious attention is dissociated away from on-going physical processes. Perhaps you’ve had the experience of arriving upstairs, but being unaware of what you came up for….

Dissociation is perhaps the most significant marker of Hypnosis, and can be of two types. With dissociated Control, your conscious mind is unaware of a command given to your fingers, so that they seem to move ‘by themselves’; with dissociated Monitoring, your conscious mind is unaware that your fingers have moved, until you notice that ‘somebody moved them’. With careful use of language, it should be possible to give Suggestions for the particular type of Dissociation required for a certain application.

There are subtleties in precisely how to apply dissociation at different levels of chunking. It can be utterly disruptive to divert the attention suddenly to a lower level of chunking. This is what happens if a tennis player is serving wonderfully, until you ask them “Exactly how do you throw the ball up in preparation for your serve?” The balance between conscious and unconscious processes is upset, and the player’s game may collapse entirely. Paralysis by analysis! But contrariwise, it can be very helpful to suggest to a violinist that they engage their mind more with the sensual grain of the experience of drawing the bow across the string. The wrong kind of focus on technique can be counter-productive, the right kind of focus on detailed perception can be inspiring.

A teacher demonstrating often has to dissociate in order for the conscious mind to direct a running commentary on the actions being demonstrated, whilst the actions themselves remain under unconscious control. One learns a lot, by teaching in this way, and it makes an interesting exercise for students to attempt. A similar dissociation allows advanced performers to analyse their own technique with sharp focus but a certain detachment that keeps one relaxed.

Chunking & Dissociation

Anchors

The NLP concept of an Anchor is rather like the bell Pavlov rang for his dogs. In training, ideally in hypnosis, the student programs himself for success by linking a certain stimulus to a desired response. As you walk out on stage, you take a deep breath, you feel your shoulders relax, and your whole body feels warm and relaxed, with a pleasant sensation of calm, confidence and concentration. Many performers have warm-up routines and pre-show rituals that function as Anchors to confident performance.

If the response is required only when called for in special situations, you can Anchor it to a highly specific trigger – when you clasp your hands that other way and breathe out slowly, you will relax and go into Flow. If the response is required automatically, you can Anchor it to an unavoidable trigger – as you walk out on stage, you enter The Zone.

NLP has methods for de-activating unhelpful triggers, typically by re-Anchoring them to a better response. It’s very difficult to inhibit an Anchored response, once it has been Triggered, so these methods rely on getting the Trigger to fire the new response first, before the old, unhelpful response can kick in.

Memory itself is an Anchored response, which functions best if the environment at the time of memorising matches the conditions at the time of recall. Hypnotists use small signals to Anchor key words: Flow, Relax, Concentrate. Language-teaching programs using hand signals, and baroque gesture (stylised signs linked to the text) work the same way. For musicians, the score itself (being read or performed from memory) provides a series of Anchors, whether deliberately created for positive results, or unconsciously built through anxiety or mistakes in the practice-room, causing negative responses.

Careful choice of vocabulary (in teaching, and in the self-talk of inner dialogue) ensures that the correct Anchor is Triggered, and unhelpful responses are avoided. If there is a command vocabulary that you associate with a bad response, then avoid using those instructions. For example. sometimes the word “Relax” only makes people more tense!

On the positive side, if you find your way into Flow by imagining the Star Wars ‘Force’, then continue to use ‘The Force’. But if the words ‘Magic’ or ‘Altered State of Consciousness’ work better, use them. Whatever works for you! Set the Anchor you can believe in, and reinforce it with constant repetition in easy circumstances: then it will work for you when you need it the most. The best situation for setting an Anchor is trance. Then use that Anchor, deliberately, even when the circumstances are so undemanding that it’s hardly required: then the Anchor will be strong enough to keep you safe in difficult situations.

To be continued…

In the second part of this paper, I’ll discuss in more detail what Flow is, how to get into it, and how to avoid losing it. You can also read more at TheFlow.Zone, here.

And the next time you read one of my blog posts, you’ll find it even easier to enter Flow.

Coming back to normal consciousness now …. 3: becoming more aware of your surroundings … 2: feeling wonderful …. 1: fully alert, now!

The Flow Zone

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our websites www.TheHarpConsort.com

www.IlCorago.com and www.TheFlow.Zone

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago, and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions.

www.historyofemotions.org.au