Claudio Monteverdi’s most famous work, the 1610 Vespers of the Blessed Virgin Mary, evokes all the glory of the Italian seicento, combining plainchant melodies, exquisite polyphony and the drama of the newly invented operatic style. This Vespers has been linked with the cathedrals of St Peter, Rome and St Mark, Venice, but the inclusion of the Gonzaga family fanfare (also featured in Monteverdi’s 1607 opera, Orfeo) confirms a stronger link to the church of St Barbara, Mantua.

The publication of the Vespers in 1610 places this collection of religious music in the context of the first operas – Cavalieri’s Anima & Corpo, Peri’s and Caccini’s Euridice all in the year 1600 – and Shakespeare’s plays (e.g. Hamlet c1600); of Caccini’s secular songs Le Nuove Musiche and Viadana’s sacred Concerti Ecclesiastici, both 1602); of Monteverdi’s own operas Orfeo (1607) and Arianna (1608); of Agazzari’s continuo treatise Di suonare sopra’l basso (1607); and of the publications of Orfeo (1609) and of Capo Ferro’s famous swordfighting treatise, Gran Simulacro (1610).

The title-page of the collection refers to some Sacred Concertos ‘suitable for the Chapel or a Princely chamber’. Musicologists debate whether these pieces are substitutes for the plainchant Antiphons specified in the liturgy of Vespers, or independent, non-liturgical additions. Either way, they alternate with the Vespers Psalms to create a fascinatingly varied publication, or indeed a modern concert. The size of the ensemble and the complexity of the music increases from one piece to the next. Meanwhile, the term ‘sacred concertos’ recalls Viadana’s publication for voices and continuo, suggesting that Viadana’s technical advice might be applied also to Monteverdi’s music. That advice emphasises the subtlety and delicacy of the ‘sacred concerto’ style, to be performed with solo voices. Viadana also gives detailed instructions for realising the continuo.

The ‘sacred concerti’ most obviously demonstrate Monteverdi’s modern style, his secunda prattica, but even if the psalm settings are more conservative, with plainchant cantus fermus throughout and exquisite polyphony, they too are full of variety. Each Psalm exploits different techniques. Dixit Dominus weaves the plainchant into rich prima prattica polyphony, and also into fashionable soprano or tenor duets. Choral recitation on a single note might be heard as highly conservative and derived from liturgical chant, but it also suggests the most up-to-date styles of operatic recitative and dramatic madrigals, for example the choral recitation in Monteverdi’s Sfogava con le stelle. Instrumental ritornelli add another fashionable touch to this Psalm.

Laudate Pueri explicitly calls for eight solo voices (not a large choir), which Monteverdi combines in many ways: as a single ensemble, as two four-voice choirs, and in pairs of equal voices. Laetatus is unified by its catchy walking-bass, another modern touch. Nisi Dominus and Lauda Jerusalem might appear similar, both for double choir, but are quite different. The block contrasts of Nisi remind us of the first metaphor of the text, God as the heavenly builder, whereas in Lauda the alternations of the two choirs come faster and faster, until the voices overlap.

It is not known if the 1610 Vespers was ever performed in the composer’s lifetime – perhaps its constituent parts were assembled only as an attractive package for publication – but it has become a world-wide baroque hit, a tour-de-force of early baroque vocal, instrumental and ensemble skills, and an icon of seicento style.

The original print has 8 part-books. Additional parts (voices or instruments) are included here and there amongst those books, but the combined parts are carefully layed out, with page-turns synchronised so that the books could well have been used in actual performance. If they were, then the combination of voices, or voice and instrument, in a single book, gives interesting information about the spatial positioning of the performers. It is noticeable that Monteverdi does not write Echos into a different partbook, even when an additional performer and an additional partbook are available: there is no change of performer or partbook when the music changes from a duet of equals to echo effects.

The Bassus Generalis partbook has a short score, since the entire performance would be guided by the continuo (as Agazzari tells us in 1607). But otherwise, no original score exists, only the individual partbooks. And there are significant differences between the Bassus Generalis and the other partbooks.

On 1st June 2014, the Cathedral of St Peter & Paul, Moscow, was filled to capacity for a landmark concert, the first-ever performance in Russia of the Monteverdi Vespers, which I had the honour to direct. Amongst many musicians and early music fans in the audience, distinguished guests included prominent Russian opera directors & international conductors, leading arts journalists, representatives of several Christian confessions, even the great-grandson of Giuseppe Verdi. The concert was the flagship event of the festival La Renaissance (artistic director Ivan Velikanov), produced by the Moscow Conservatoire and supported by the French Cultural Institute. The performance was recorded and broadcast by Russia’s largest classical music station, Radio Orphee.

Vocal and instrumental soloists were brought together from Moscow, St Petersburg, Ukraine, Lithuania, Colombia, France, Germany and UK. Many of the team have worked together with me in previous baroque projects in Russia, including the first baroque opera – Cavalieri’s Anima e Corpo (1600), soon to begin its fourth season in repertoire at the Natalya Satz Theatre Moscow in Georgy Isaakian’s Golden Mask-winning staging; the first staged production in modern times of Stefano Landi’s La Morte d’Orfeo (1619) – with the International Baroque Opera Studio and Il Corago at the St Petersburg Philharmonia last December; and the compilation I made of Shakespeare’s Musicke at Festival La Renaissance 2013.

Even though there are many fine modern performing editions available, I made a new edition for this project. The new edition re-examines some questions, but does not make too many startling new choices. Rather, it presents all the information- including the variants in the Bassus Generalis book – at a glance, so that performers can make their own choices. Continuo players had (my transcription of) the original Bassus Generalis partbook to play from. At first they found this disconcerting, since it is not a complete score, but we gradually discovered the benefits of not having a full score. The original notation encourages continuo-players to play simply, structurally, and to lead in steady rhythm, rather than trying to follow the singers.

Some singers also experimented with singing from facsimile of the original partbooks – they are clearly printed, and have very few mistakes, apart from the usual miscounting of rests. (That is to say, the original printers miscounted the rests, not our singers!).

The Moscow concert reflected state-of-the-art Historically Informed Performance practice. Solo voices (rather than a large choir) offered the listeners direct, personal communication of the text, whilst still creating impressively sonorous tuttis in the clear but generous acoustic of the Cathedral (a large building, but on the scale of St Barbara, Mantua rather than the enormous spaces of St Marks Venice or St Peter’s Rome). The chiavetti notation of the final Psalm and Magnificat was respected, so that these movements were transposed downwards to the standard renaissance vocal line-up, with high tenors (not falsettists) on the Altus parts. Cornetts, sackbuts and strings played only where called for by Monteverdi, creating dramatic contrasts by their appearances, and a more intimate atmosphere when they were silent. As the original part-books require, the famous Echos were sung and played from the same positions as the principal solos, with echo-performers turning away from the listeners to allow the acoustic to create a natural echo effect (rather than trekking off to some remote location).

And of course, we used quarter-comma meantone: there was certainly no thought of introducing the anachronism of the modern early music scene’s “one size fits all” Vallotti temperament (from the year 1779).

Most significant, and immediately visible to the audience, was the absence of a conductor. The entire performance was guided (just as period sources describe) by the instrumentalists of the continuo section (organ, regal, theorbos and harps), with each singer taking individual responsibility for maintaining the steady beat of the baroque “Tactus”.

It is well known that music was not conducted in this period, but nevertheless even specialist Early Music ensembles often introduce the gross anachronism of a modern conductor.

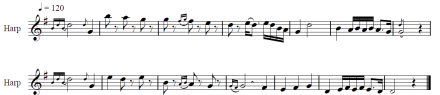

The project also benefitted from the latest research findings of my Text, Rhythm, Action!investigations for the Performance program of the Australian Research Council’s Centre for the History of Emotions. In Monteverdi’s Rhythm, the steady beat of the Tactus represents the perfect clock of the cosmos, the Music of the heavenly Spheres. Just a couple of decades after Galileo’s discovery of the pendulum effect, seicento music itself is still the most precise clock available on earth, with duple and triple metres alternating in regular Proportions. The Tactus is a rhythmic heartbeat, maintained throughout the whole work (except for certain movements where Monteverdi specifically indicates a more relaxed speed). With no anachronistic conductor, there are also no arbitrary changes of tempo. As a result, the composer’s notated contrasts of activity are more effective. (See Rhythm: What Really Counts here and also The Times they are a-changin’ here )

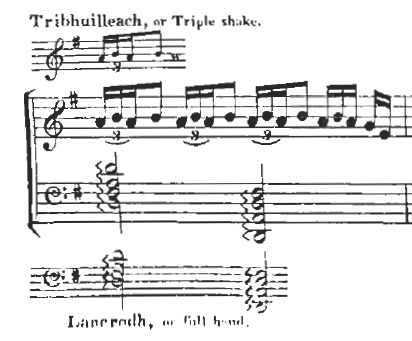

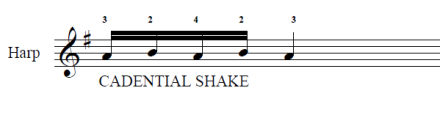

All this ancient philosophy was put to practical use in rehearsals, with a lot of time spent working on Text and Rhythm. With no conductor at the front, all the singers took on the role of “conductor”, beating time in seventeenth-century style, with a slow, constant down-up movement of the hand, like a pendulum moving for one second in each direction. When the music changes into triple metre, the fast Proportion of Tripla is counted down-two-three, up-two-three. But the Proportion of Sesquialtera counts a slow three against the two movements, down-up, of the hand. This slow Proportion is less familiar to today’s baroque musicians, but it occurs much more often in the Vespers than in secular works.

In another rehearsal exercise, we asked the singers to use their hands to show the accented syllable of each Latin word, the so-called Good syllable. Sometimes these word-accents coincide with the Tactus, sometimes they are syncopated against it. This exercise helped bring out the lively rhythms and syncopations of Monteverdi’s writing. Using the hand to show the Tactus kept the ensemble together and made the music safe: showing the Good syllables emphasised contrasts and made the music interesting.

In a development of the Good syllable exercise, we varied the hand-movement to make it long and sustained or quicker, depending on the length of the Good note. This helps to bring out the contrasts in Monteverdi’s notated note-lengths, and the long, sustained accents create a thrilling, emotionally committed sound, especially when one particular voice has long accents where others do not.

But the highest priority in early baroque music is the Text. As a madrigalist and opera composer, Monteverdi responds passionately to the poetic imagery and dramatic Action of the Vespers texts. His music for the Magnificat verse Quia respexit sets the Annunciation scene with high wind instruments (played ‘with as much force as possible’) representing the Spirit of God. Pairs of quiet instruments suggest the dialogue between the Angel Gabriel (sackbut) and Mary (flute), before the whole ensemble plays again for omnes generationes: ‘all generations shall call me blessed’.

In rehearsal, we discussed in detail the meaning of each verse, and what significance the texts would have for seventeenth-century listeners. Although this was not a theatre project, we did explore in rehearsal the baroque gestures that would be used for similar words on stage, as a way to experience the emotional force of particular words. Even in performance, hand gestures were used, but with appropriate decorum, suited to liturgical music in the sacred space of the church. But the most useful rehearsal exercise was to combine a hand-gesture on the Good syllable (this optimises the sound of the text) with simultaneous concentration on the meaning of that particular word (this synchronises the emotions of the text).

Rehearsing the text in this way revealed to us how Monteverdi cast particular voices in certain roles, just as one would find in a baroque opera. A duet for two tenors is a favourite seicento device, and obviously suits a text about two angels, Duo Seraphim. When the second part of the text begins Tres sunt (there are three), the appearance of a third tenor transforms the musical texture into something rich and strange, appropriate not only to the simple number three, but even to the divine mystery of the Trinity which the text continues to expound.

In the Psalm, Laudate Pueri, a tenor duet at the words excelsus super omnes gentes is again a conventional choice. But here the plainchant cantus firmus is given, rather unusually, to high soprano, vividly illustrating the text “in the highest heaven, above all the people”. In that same Psalm, a bass duet is a most unusual choice – there are very few duets for basses in the entire repertoire. But here, and again in the Magnificat, this combination (deep sounds, and the super-human effect of two powerful voices at once) represents God himself: Quis sicut Dominus Deus noster? (Who is like the Lord our God?) and sanctum nomen eius (Holy is his name).

In the verse et de stercore erigens pauperem , low voices paint the picture of the mire out of which God (slow triple metre) lifts up (a rising sequence) the poor man (a solo tenor). Just as in some of his polyphonic madrigals, here Monteverdi seems to cast the solo tenor as if personifying the protagonist’s role. So this singer is featured again,reciting on a single note (is this plainchant or operatic recitative?) amidst the eight-voice tutti at the words ut collocet eum cum principibus populi sui – placing him amidst the princes of God’s people. It is surely the deliberate touch of an opera composer to cast this tenor as the poor man, so that the audience – or liturgically, the congregation – sees this same man literally placed amongst the princes as he sings his solo amidst the choir, clergy, cardinals (princes of the church) and other nobility in the courtly chapel or chamber.

Just as earthly music was considered to be an imitation of the perfect, heavenly Music of the Spheres, so actual dancing was an earthly imitation of the divine dance of the stars in their orbits. This explains why there are so many slow, Sesquialtera Proportions in the Vespers, whereas Monteverdi’s opera Orfeo more often has fast Tripla. Of course, the slower movement of Sesquilatera sounds better in a church acoustic, whereas fast Tripla sounds good in a less resonant theatre. But more significantly, the sacred spheres were thought to rotate more slowly than the sublunary sphere of the earth, so a slow triple Proportion was the ideal musical emblem for the divine Trinity.

Fast, we might even say ‘secular’, Tripla dance-rhythms in the Vespers paint texts that call for divine assistance down here, on earth: Domine ad adjuvandum me festina (O Lord, make haste to help us) and Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis (Holy Mary, pray for us). And another Tripla depicts the speed of arrows in the hand of a giant sicut sagittae in manu potentis.

It is this passion for visual detail, even in a musical setting, that – according to renaissance philosophy and period medical science – conveys the emotions from the text to the listeners, in order to move their passions, muovere gli affetti. This intense, emotional visualisation by composers, performers and audiences is the focus of one of my current research strands: Enargeia: Visions in Performance.

During the project, we explored in great detail questions of Proportions and Frescobaldi’s advice for Driving the Time – guidare il tempo. These discussions helped shaped the arguments in a later blog post on the Frescobaldi Rules here, and I’ll return to the subject in future postings.

For the coming season, further Early Music productions are planned in Moscow, St Petersburg and around the country: the first Russian performance of the earliest Spanish opera, Calderón and Hidalgo’s Celos aun del aire matan (1660); the production team Il Corago with the medieval Ludus Danielis; and another historical production from the International Baroque Opera Studio.

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our website www.TheHarpConsort.com .

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago. From 2011-2015 he was Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions.