There are many possible routes towards an understanding of basso continuo. As an academic discipline, it’s often associated with the study of musical grammar, harmony and voice-leading: ‘Harmonise this chorale melody in the style of Johann Sebastian Bach’.

Some performers might – like me – have begun their study with the printed realisations in modern editions: thinning out rich, mid-20th-century piano parts; enriching minimalist sketches; adding some improvisatory touches and trying to filter out what is stylistically inappropriate.

Often the harpsichord is assumed to be the epitome of historical style, and the combination of cello and harpsichord to be the ideal mix of melodic bass and chordal harmony, perhaps with a double-bass to add gravity.

There is a strong modern tendency to think in terms of an ideal realisation, with the ‘correct’ harmonies. In this view, a perfect (in every way!) cadence should be figured 53 64 54 73 over the dominant – other options are seen as variants of this ‘standard’ harmonisation.

But a moment’s reflection will suggest that over some two centuries of the basso continuo age, the ideal of a ‘perfect’ realisation must have changed. Like any other aspect of performance practice, the aesthetics of Continuo must differ according to period and national style. C.P.E. Bach’s admirably detailed instructions do not apply to Peri, Johann Sebastian’s wonderful harmonies are no guide to Caccini, Rameau’s aesthetic is not the same as Monteverdi’s.

And in Continuo studies as in any historical investigation, we must beware of teleology, of the dangers of ‘looking backwards into the past’. It is all too easy to approach the beginnings of Continuo via Bach, and to view both Bach and Monteverdi through the distorting lens of modern assumptions (whether in ‘common practice’ or ‘early music’).

So I suggest that it’s well worthwhile to start at the very beginning, and consider the earliest sources for Continuo. Those first treatises should be our guide for the early 17th century, and they should also be our starting point from which to follow a chronological path towards Corelli, Lully, Bach and beyond.

One of the most interesting early sources is Agostino’s Agazzari’s 1607 Del Sonare sopra’l basso con tutti li stromenti e dell’ uso loro nel Conserto (About playing from the basso part with all instruments, and about their use in ensemble). See my posting What is Music here for links to a facsimile, translations and commentaries.

The reference to uso shows that Agazzari’s intent is thoroughly practical. His treatise is not lost in the clouds of metaphysical speculation (Science), nor concerned about theoretical principles governing the Art of Music. And he doesn’t waste time expounding lots of rules for playing from unfigured bass, since composers often create surprising harmonies as they imitate the passions of particular words. Agazzari prefers to write in the figures as necessary, though he emphasises that all cadences, intermediate or final, end on a major chord. His focus is consistently on the practicalities of playing from a new notation (the basso, whether figured or not, now regarded as the best guide to the structure of the whole piece, rather than a score or intabulation).

Agazzari discusses in detail what each kind of instrument should do, and categorises his material in various different ways. He distinguishes between wind and string instruments. Other than the organ, winds are excluded from delicate ensembles because they do not blend, though the trombone can serve as a low bass when only a small (4-foot) organ is available. Other wind instruments might be acceptable, if played expertly and dolce.

Amongst string instruments, he mentions those which are capable of perfetta armonia di parti (perfect structure of counterpoint – the word armonia means well-structured organisation, not just ‘harmony’): Organ, gravicembalo (large harpsichord with low basses), Lute and arpa doppia etc.

Other instruments can play harmonies (in the modern sense), but not fully correct counterpoint (not all the armonia, in the period sense): cittern, lirone, guitar. A third group of instruments offers fewer chordal (let alone contrapuntal) possibilities: Viola da gamba, violin, pandora etc.

Players are expected to have three separate but complementary skill-sets: a knowledge of armonia (counterpoint, rhythm and proportions, all the clefs, dissonance and resolution, when to play major/minor thirds or sixths etc); total familiarity with their instrument and with playing from score or intabulation; excellent aural skills and awareness of the movement of individual polyphonic voices.

Agazzari champions the practice of playing from the basso as useful in three ways: for the new style of singing dramatic music, lo stile moderno di cantar recitativo; as easier than reading, especially sight-reading, from a score or intabulation; and as a very concise and compact notational system.

But the most significant binary distinction he makes , one that he repeats several times within this short treatise, is to categorise what is played ‘on the basso’ as either Structure – fondamento ( a word that occurs 9 times) – or Decoration – ornamento (4 times). Meanwhile, we should note that the word continuo does not occur anywhere in this document.

Agazzari frames his entire discussion in these terms – Structure versus Decoration – introducing these two ordini (categories) at the very beginning of his argument. We should therefore be very careful to link each piece of advice to the relevant category. We should think too about how the various bi- and tri-partite categorisations mentioned above intersect with those most significant ordini of Structure and Decoration. And how does the concept of Continuo fit with all this?

Simply to pose this question points us towards the answer. The essential function of Continuo is fondamento: Structure (organ, harpsichord, theorbo, harp).

Meanwhile, the function of Decoration, ornamento, is condire – to spice up the ensemble with delicious tone-colours (lirone, cittern, guitar etc) or clever division-playing, scherzando e contrapontegiando (having fun and playing counterpoint, on lute, violin etc). Agazzari includes division-playing here for highly practical reasons: divisions can now be improvised whilst reading from the basso part, rather than from a score or intabulation.

Looking backwards into the past, we might be tempted to conflate these two functions, to imagine that Agazzari was writing about ‘two ways to play Continuo’. But his book is not called ‘How to play Continuo’, it’s ‘about playing from the basso’.

Moving chronologically forwards with Agazzari from the late 16th into the early 17th century, we can see that he is linking the uso moderno, a new use of notation (playing now from a basso, rather than a score or intabulation) to two distinct practices: structural accompaniment and fun decoration – scherzi. And he is very careful to keep the two practices distinct.

The structural foundation – Agazzari’s fondamento -is what we now call Continuo (organ, harpsichord, theorbo, harp).

Some instruments with interesting tone-colours (lirone, cittern, guitar etc) can play a chordal accompaniment (which we might well today call Continuo), but Agazzari does not class these as fondamento because they cannot play the actual basso. Nevertheless, we have clear evidence from other sources that such instruments were sometimes used as the sole accompaniment.

Otherwise, Decoration – ornamento – consists of division-playing. This ‘spice’ should of course be flavoursome and tasteful. And advanced division-playing even includes the invention of additional counterpoint. But it’s not Continuo.

As Bernhard Lang (2003) comments here, Agazzari’s advice on ornamento-playing can be seen in the context of earlier division manuals by Ganassi (1535), Ortiz (1553) and dalla Casa (1584). Agazzari’s contribution is to compare the different division-playing styles of particular instruments, inviting them all, even violinists, to improvise whilst reading from the basso part.

The other job, Continuo-playing, is described in the other part of Del Sonare sopra’l basso, in the paragraphs referring to Structure, fondamento. As Agazzari reminds us, we should not confuse the two roles –

hanno diverso ufficio, e diversamente s’adoperano (they have different jobs, and are managed differently).

But all too often today, we hear Continuo-bands playing divisions, playing divisions simultaneously (but not quite together!) on several instruments, and playing divisions on fondamento instruments. We even hear Continuo competing with the singers or solo instruments in the treble register – precisely the zuppa e confusione, cosa dispiacevole (soup and confusion, a displeasing thing) that Agazzari warns against!

Even in division-playing, whenever several instruments play together, Agazzari tells us that they should take turns to add ornamento, one at a time. They should not compete ‘like sparrows, all at the same time: and let’s see who can shout the loudest’!

Lang also comments on the seicento trend for the fondamento to be less contrapuntal, more chordal, assembled vertically over the basso. And Agazzari leaves us in no doubt that in general, too much polyphonic complexity, too much concentration on contrapuntal imitation, is contrary to the new aesthetic:

By the rules of counterpoint these might be good compositions, but nevertheless by the rules of good and true Music they are vitiose – vicious, faulty, sinful, defective, imperfect, false, corrupted, blemished, full of vice, unsound, crazy, and worm-eaten (according to Florio’s 1611 dictionary).

And that comes from not understanding the purpose and the job, from forever wanting merely to observe counterpoint and imitations of notes, rather than of the affetto (passion) and semblance of the words.

So with that stern warning and the condemnation of sparrow-flavoured soup ringing in your ears, I invite you to compare Agazzari’s point by point instructions for fondamento with what you hear, listening to Continuo in concerts and recordings today. Continuo-players, keyboardists especially, might like to compare Agazzari’s recipes with their own playing in early seicento repertoire.

- The Continuo are those which guide and support the whole body of voices and instruments in the ensemble.

- They are Organ, gravicembalo etc (and for smaller ensembles) Lute, Theorbo, Harp etc

The job of ‘guiding’ or ‘directing’ – guidare – reminds us of the crucial importance of rhythmic Structure. Rhythm is a significant element of 17th-century armonia, and Caccini makes it a priority, along with the Text.

Agazzari links ‘support’ to grave resonance and low-octave basses (see below).

- When playing Continuo, you have to play very judiciously, watching out for the entire ensemble…

- Playing the piece as straight and accurately as possible, not making passages or divisions, but helping with some low-octave bass notes, and avoiding the high register.

Many of the earliest figured-basses show exactly where the harmonies change over a sustained bass, by writing the rhythms of the harmony changes into the basso itself. (The repeated bass notes are then tied together, to show that they are not re-struck). Such precise notation, combined with Agazzari’s instruction not to ‘break’ a bass-note and with the growing seicento tendency to think vertically over the bass (rather than horizontally in counterpoint), suggests that Continuo-players should as far as possible avoid in their realisation any activity (especially harmony changes) that is faster-moving than the basso itself.

So if the basso moves in minims, say, your realisation should also move in minims, not in crotchets and quavers. In general, we expect the entire fondamento to reflect the rhythms of the basso, and typically to be less active than the composed contrapuntal parts.

- Don’t double the soprano, don’t play divisions and ornaments in the high register…

- But it’s good to play with great restraint (or perhaps, very compactly), and grave (low, weighty, serious: Florio gives ‘grave, solemn, important).

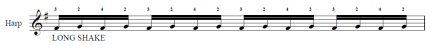

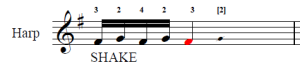

Grave is also used to characterise the violone, which plays ‘as much as possible on the thick strings, often with low-octave basses’. The re-entrant tuning of the theorbo and the triple-stringing of Italian baroque harp allow compact chords, with a lot of supportive resonance all packed into the grave register: both instruments have low-octave basses, as does the gravicembalo (literally, grave-harpsichord).

Note Agazzari’s emphasis that the fondamento should play ‘very judiciously’, ‘with great restraint’. No chirping sparrows!

- The Continuo holds the tenor – the underlying harmonic/rhythmic sequence, for example a ground bass (see Ortiz) and the armonia –the complete structure, both harmony and rhythm – ferma – firm, steady, fixed, sure (Florio).

In large ensembles, certain instruments have well-defined roles. When, for example, harpsichord and theorbo play together, it is the theorbo that should make some divisions (on the bass strings), whilst the harpsichord provides a fondamento grave. Agazzari’s advice is confirmed by the allocation of particular instruments to alternative bass-lines in scores by Landi, Veracini etc. The more complex basso is for lute, theorbo, or harp: the simplified part is the fondamento for harpsichord.

The role of the keyboard, whether organ or gravicembalo is entirely Structural. (Small spinetti might provide Decoration). Today, this custom is more honoured in the breach than in the observance !

Nowadays a lot of zuppa e confusione is created by inappropriately applying to Continuo-playing Agazzari’s suggestions for ornamento, whilst ignoring his warnings against chirping like competing sparrows. But his advice on fondamento is repeated in many other period sources, especially for musica recitativa, where it’s generally agreed the accompanist should play grave and not add ornaments.

The frontispiece to Del sonare sopra’l basso illustrates tutti li stromenti, with the organ, Agazzari’s own instrument, enthroned above. In the Academy of the Intronati, Agazzari’s nickname was L’Armonico intronato (well-structured musical organisation, enthroned). Below two shields show the heavenly orbits, with the caption ex motu armonia (cosmic movement produces armonia) and what might be the infernal pit, with the caption nec tamen inficiunt (and, however, they don’t create chaos – literally ‘un-make’).

So I give Agostino the last word:

Just take this as it is, and forgive me for the lack of time to write more.

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our website www.TheHarpConsort.com . Further details of original sources are on the website, click on “New Priorities in Historically Informed Performance”

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago, and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions.

www.historyofemotions.org.au