This is a slide-show introduction, based on lecture given to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Theatre Natalya Satz, Moscow (the original home of Peter and the Wolf), following the 45th performance of the theatre’s award-winning production of Anima & Corpo. Nevertheless, this post draws on the latest research findings, and there may be some surprises, even for seasoned baroque fans!

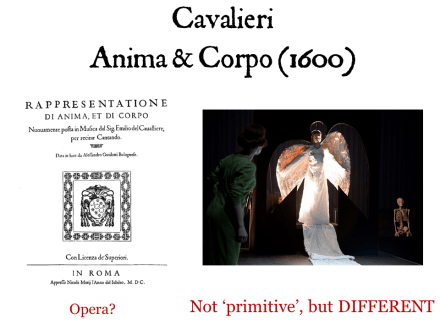

Emilio de Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima e di Corpo (1600) is indeed the ‘first opera’. Jacopo Peri, whose Euridice was performed later the same year, acknowledges Cavalieri’s role as originator of the style. (Earlier music-dramas by these two composers, notably Peri’s Dafne, have not survived.) So why would Cavalieri and his contemporaries seek to develop a new theatrical genre of fully-sung plays?

17th-century writers were still re-telling a story going back via Quintilian and Cicero to Demosthenes (4th cent. BC). The question was posed:

What are the three secrets of great performance?

Demosthenes’ first answer was “Action!”. And his second answer was “Action!”, And his third answer was also “Action”.

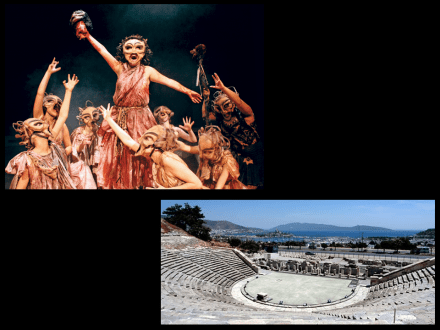

Meanwhile, in the decades before the year 1600, philosophers of performance were impressed by the emotional power of the ancient Greek and Roman dramas, which (they believed) had been fully sung. So Cavalieri and his colleagues wanted Action in their music, and Music in their dramas: fully-sung music-drama was the epitome of their beliefs in the power of performance.

The modern label ‘first opera’ encourages us to consider all that came after Cavalieri. But to understand his work, we need to view it in its own historical context. And we should be cautious: even though this is sophisticated, dramatically powerful, fully-sung music-theatre, Cavalieri did not call it ‘opera’. It is a Rappresentatione, a ‘show’. It is not ‘primitive’, but it certainly is different from our modern expectations.

Not ‘primitive’ but DIFFERENT…

… might well be our motto, as we climb into our time-machine in order to explore Planet Earth, circa 1600.

This was an age of impressive architecture: as assistant to Michelangelo, Cavalieri’s father Tommaso was closely involved with the building of St Peter’s Rome. Painting became ever more dramatic, culminating in the chiaroscuro of Caravaggio. Even religious subjects were depicted with theatrical bravura: Tommaso de Cavalieri was the model for Adam in Michelangelo’s frescos for the Sistine Chapel.

The exploration of the Americas continued, charted by sophisticated world maps. Galileo trained his telescope on the moons of Jupiter, and also experimented with gravity at the tower of Pisa.

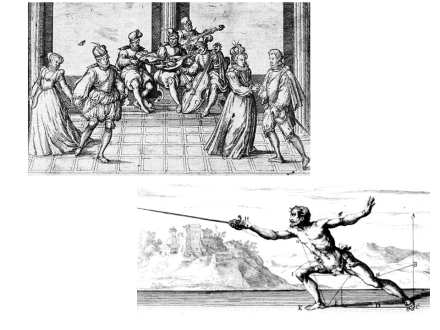

Italian ladies and gentleman at court would spend much of their time making music in madrigal groups or consorts of viols. Several hours each day would be spent learning and performing new social dances. And a couple more hours daily were devoted to practising swordsmanship, with the fashionable rapier, well over 1 metre long, with a needle point and razor-sharp edges.

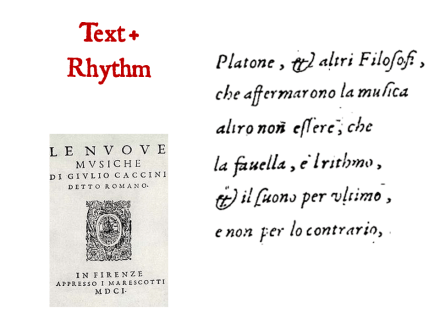

There was plenty of new music. Cavalieri’s opera was quickly followed by Caccini’s Le nuove musiche (1601/2), the first collection of songs with continuo-bass accompaniment, which includes the famous Amarilli, mia bella. In 1607, Monteverdi’s ‘story in music’ Orfeo was performed: Aggazzari’s treatise from that year, Del sonare sopra’ l basso explains how many different kinds of instrument could improvise accompaniments from the same continuo-bass notation. In 1610, Monteverdi’s magnificent Vespers mixed old-style polyphony with the new techniques of continuo-song; Capo Ferro’s survey of rapier swordsmanship is from the same year. In England, this was the age of Shakespeare’s plays (full of music, of course) and Dowland’s melancholic lute-music.

In 1609 Dowland also translated into English an influential book on singing, Ornithoparcus’ Micrologus, in which he emphasises the particular importance of rhythm.

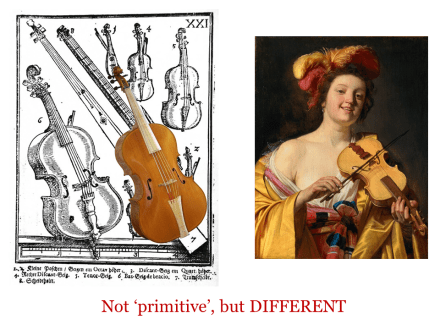

Instruments

Violin-family instruments from the late 16th century are still regarded today as the finest ever made. Praetorius’ 1619 diagram shows violin, viola, cello and related instruments, together with a surviving cello by Amati. Nowadays, these wonderful instruments have been altered, by changing the angle of the fingerboard to increase the string tension. But around 1600, violins were held in a relaxed way on the shoulder, were strung more lightly, and were not encumbered by chin-rests, tuning screws and shoulder rests. With its original set-up, the instrument is not as loud as a modern violin, but is more direct and responsive. If a modern violin is like a big, luxurious limousine, then a baroque violin is like a sports-car: lighter, more manoeuvrable, and (I would say), more fun to drive!

The early-17th-century predecessor of the oboe was the Shawm, which was made in various sizes from soprano to bass. The double-reed is surrounded by a wooden ‘pirouette’ to support the player’s lips. The Dulcian is the ancestor of the bassoon, and also came in various sizes from bass to soprano. Whereas nowadays we consider oboes to be the high register and bassoons the low register of a single ‘family’ of instruments, in Cavalieri’s time they were two distinct consorts, each with a complete range from treble to bass.

Baroque trombones, known in English as Sackbuts, have a narrower bore than their modern descendants. Like baroque strings, they are not as loud as modern instruments, but more precise and flexible in their sound. Praetorius shows the trombone family from bass to alto. The upper register of this consort is represented by the Cornetto, made from wood, with leather wrapped around it. It has a wooden mouth-piece similar to a trumpet’s, and finger-holes in the tube similar to a flute. The sound is somewhere in-between a trumpet and a flute, and was considered in this period to be the closest to the sound of the human voice. That gives us a clue to the sound-world of circa-1600 singing: not as loud as modern opera singers, but clear, precise and very flexible.

Trumpets and drums were originally military instruments, and are still today associated with royalty. Baroque trumpets have no valves; the different pitches, including extreme high notes, are created with sophisticated lip-technique.

We can recognise the descendants of these early baroque consorts in the various sections of a modern orchestra. But around 1600, large groups of instruments were not formed into a single ensemble, but were rather distributed around the available space in groups of 4 to 7. Each group was considered to be a ‘choir’, that might mix instruments and voices, or might be homogenous, e.g. contrasting a string ‘choir’ with a wind ‘choir’.

Continuo

You can view and download for free a full-size version of this poster here.

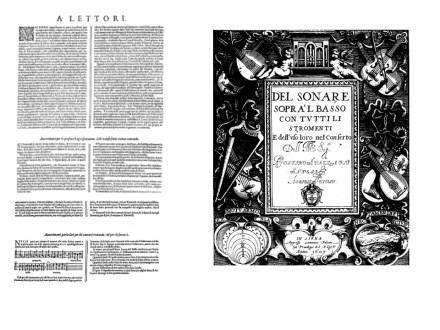

The most important instrumental section in the first operas has no equivalent in a modern orchestra. The Continuo section brings together a variety of instruments with the common purpose of providing harmonic support and rhythmic direction, guiding the entire company of instruments and voices. Like the rhythm section of a jazz-band, Continuo-players define the rhythmic structure, respond to the various soloists and add decorative touches of their own. Agazzari’s 1607 treatise Del Sonare sopra’l basso here explains how each type of instrument contributes to the Continuo.

The organo di legno, or chamber Organ, has wooden pipes, and plays sustained harmonies in the low register, to support the voices and melodic instruments.

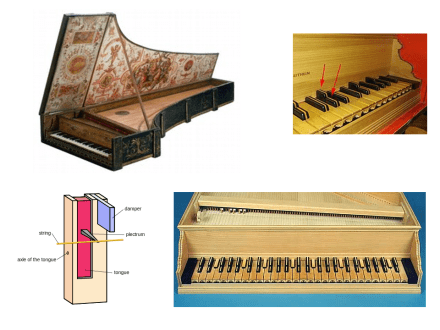

The Harpsichord has metal strings; when you press a key, a wooden jack rises past the string, so that a small plectrum (shaped from a bird-quill) can pluck the string upwards. As you release the key, the jack descends and a piece of felt is lowered onto the string to stop the sound. The sound is not as loud as a modern piano, but is clear and rhythmically precise. In this style, the Harpsichord also plays simple harmonies in the low register, defining the essential harmonic and rhythmic foundation.

The Regal, or reed-organ, has metal pipes; when air enters the pipe, a metal tongue vibrates against a metal half-tube, and this vibration is amplified by the metal resonator. The sound is strong and rather nasal. If the wooden Organ suits scenes of heaven, or pastoral idylls on earth, then the Regal is ‘the organ from Hell’!

The most essential instrument in an early Italian continuo-section is the Theorbo, also known as Chitarrone. This is the double-bass instrument of the lute family, with two necks. The strings on the first neck run over a fingerboard, and produce a strong melodic bass, with chords in the tenor/alto register. The second neck is much longer, and these strings have no fingerboard; they give another octave of sub-bass notes, that provide a powerful rhythmic impulse and a long sustain that supports the harmonic arpeggio of the upper strings.

Around 1600, the harp doubled in size in order to create a strong sub-bass register comparable to the Theorbo’s. The Italian arpa doppia (double harp) has multiple rows of strings, arranged like the black and white notes of a keyboard, so that all harmonies and chromatic changes are available, just as on the harpsichord or organ.

The harp also has a full soprano register, so that it plays a unique role in the continuo section, defining fundamental structure alongside keyboards and theorbo, and also providing decorative touches in the higher register.

The baroque guitar has a plucking technique for solo repertoire, but in the Continuo section it usually provides rhythmic energy and decorative colour by strumming.

Read more about Agazzari’s categories of fundamental and decorative instruments here.

The combination of harpsichord and cello is typical of 18th-century music. In the early 17th-century, the usual pair is theorbo and organ.

All the different instruments of the Continuo section play from the same bass-line, which may (or may not) have additional information about the harmonies indicated by figures above or below each note. But whilst they read from the same part, each player improvises the harmonies and any decorative touches according to the role and capabilities of each instrument: this is referred to as ‘realising’ the continuo.

No conducting!

One prominent figure in modern opera, the conductor who moulds the rhythm and guides the orchestra with his hand or baton, was not seen in the 17th century. Early Music was not conducted. The role of guiding the rhythm belonged to the Continuo section, as Agazzari tells us.

Of course, there would be someone to coordinate the rehearsals and make whatever decisions were needed. This job was done by Il Corago, who was usually the Artistic Director of the entire production, responsible not only for musical coordination, but also for guiding the actors, dancers, scene-builders, lighting technicians (sophisticated lighting effects were obtained from massed candles), and stuntmen (acrobats and sword-fighters). Cavalieri himself was a Corago, with a working knowledge of all of these disciplines, so that he could co-ordinate the contributions of each specialist.

When there was a large musical ensemble, it would be spatially divided into several groups, each of which would have a time-beater to synchronise the rhythm within the group and between one group and the others. The frontispiece of Praetorius’ Theatre of Instruments shows this practice in action, with a large ensemble divided into three ‘choirs’ of instruments and voices. Each choir has its own time-beater, and the three time-beaters watch each other to synchronise the beat.

Priorities

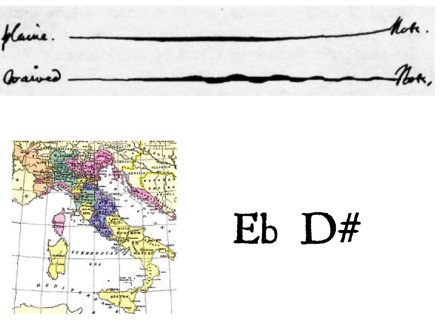

Today, discussions about Early Music often focus on the question of Vibrato. Period diagrams show the typical shape of long notes: a ‘plain note’ begins softly and then swells out (there is no vibrato); a ‘waved note’ similarly begins softly, and adds vibrato as the sound swells out.

Another topic of modern debate is the question of pitch. Around 1600, in the south of Italy, the pitch was lower than today’s standard of A440; in the north it was higher. In central Italy, it was somewhere in between. Bruce Haynes’ The Story of A here tells the History of Performing Pitch in great detail.

Subtle choices of precisely how to tune each note of a keyboard instrument or harp are studied as Temperament. Whereas on the modern piano, Eb and D# sound the same and are played from the same key, in historical Temperaments these are two subtly different pitches. Some keyboards have double keys for the black notes, baroque harps have extra strings, in order to facilitate this fine distinction. The typical Temperament circa 1600 is known as Quarter-Comma Meantone: it produces beautifully pure major thirds, making consonances sweeter and dissonances sharper.

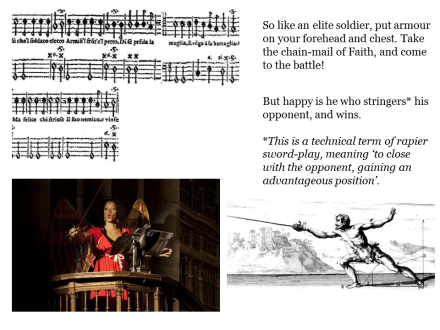

These are the hot topics amongst many of todays’ Early Music practitioners. But what were the priorities for musicians and singers performing Anima & Corpo in the year 1600? The original print is here, and Caccini’s Le Nuove Musiche tells us how to approach it:

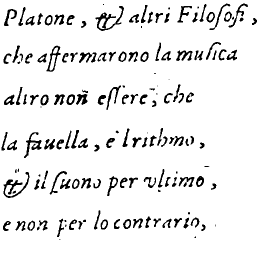

Music is Text + Rhythm, and sound last of all.

“And not the other way around”, Caccini emphasises.

These historical priorities guided my international research program into Text, Rhythm, Action! over the last five years, reported here, and I apply them in all my practical work, training musicians and directing performances for audiences today.

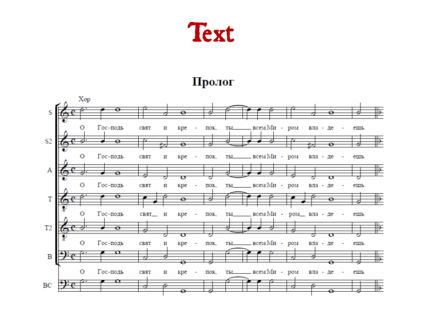

Text

Period sources insist on the importance of communicating the text to the audience, so for the production at Theatre Natalya Satz, we wanted to speak to the audience directly in their own Russian language. Great care was taken to synchronise the translation with the ‘word-painting’ of Cavalieri’s music, in which every single word is individually set to music. Poet Alexey Parin worked together with specialist musicians Ivan Velikanov, Katerina Antonenko and myself, to preserve the close links between text and music.

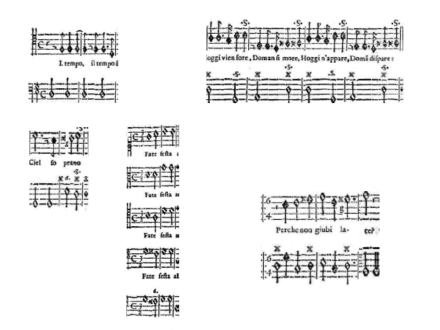

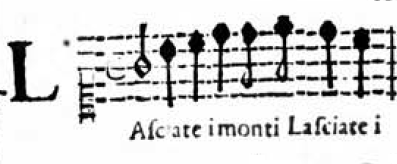

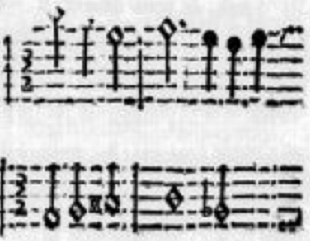

At the beginning of the drama, the first notes are immediately repeated – not because a series of repeated Fs makes a wonderful melody, but in order to repeat the word for emphasis, just as a fine orator would do: “Time… Time”.

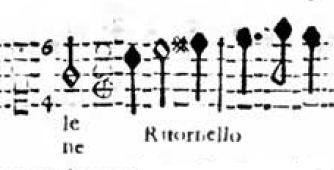

In this period, the term Aria has a different meaning; it signifies any repeated structure in words, rhythm, harmony or melody. The metric patterning of the verses Hoggi vien fore, Doman si more, Hoggi n’appare, Doman dispare [Today Life comes forth, tomorrow it dies; today it appears, tomorrow it disappears] is matched by similar patterns in the melodic contours, rhythms and harmonies of Cavalieri’s music. This, in early-17th-century terms, is another Aria, just like the repetition of the single word Tempo, along with its carefully set music.

If the text refers to Heaven above, ciel soprano, the singer will pitch his voice high. If the text mentions a party, festa, the music swings into fast triple-time. Just as an actor in a spoken play will raise his voice to indicate a question, so Cavalieri sets questions on rising pitches.

Text and music are so closely linked that many musical features are not Cavalieri’s compositorial choices, but rather his sensitive responses to the demands of the poetry. Similarly, many performance practices are not the performers’ artistic inspiration, but rather their sensitive responses to the demands of the text and the historical expectations of this musical style.

Many explanatory texts survive to inform us of those historical expectations, including a Preface with Cavalieri’s own indications how to perform this kind of music-drama, Agazzari’s treatise on Continuo already mentioned, and the anonymous c1630 guide for a music-theatre’s artistic director, Il Corago.

Rhythm

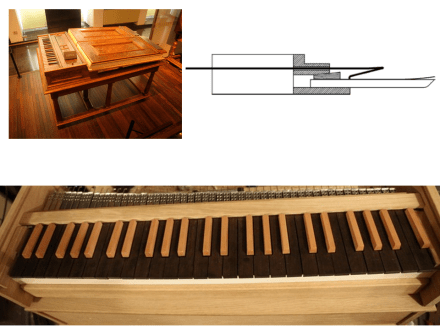

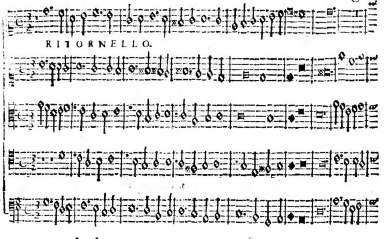

Although there were no conductors in this period, musicians, whether soloists,or in duet, trio and larger ensembles, would beat time with their hand, palm downwards, down for about one second, up for one second. This slow, steady beat was known as the Tactus. Read more about Tactus here.

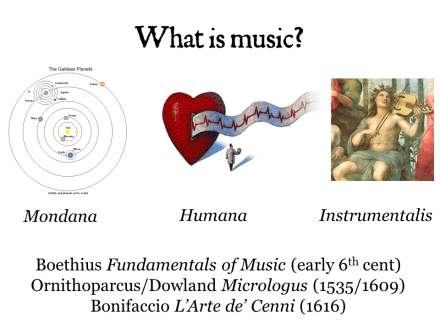

Music itself was understood to be the Music of the Spheres – mysteriously produced by the perfect motion of the stars and planets; the harmonious nature of the human body; and – last of all – actual sounds sung and played on earth. So musical rhythm represents that perfect heavenly movement, rhythm is life itself.

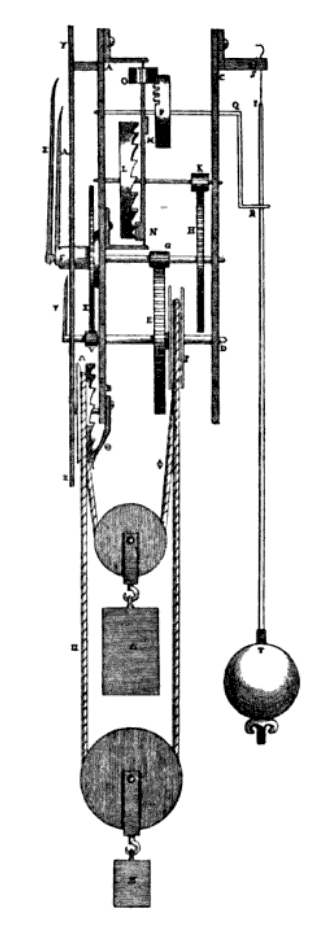

Just as clockwork produces various speeds of rotation from one fundamental movement, so 17th-century musicians perceived the different orbits of the planets to be meshed together and turned by the hand of God. This philosophy is imitated in musical Proportions, by which the constant slow Tactus beat is divided into 2, 3 or 6, to create duple, tripla and sestupla metres. A Proportion of 3:2 creates Sesquialtera metre.

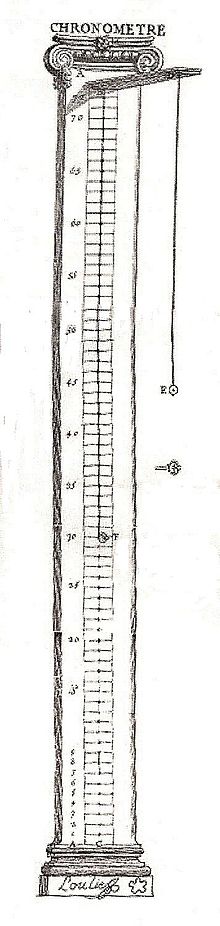

Time, like Music, was celestial and embodied, measured by the cosmos and the human pulse, better than by clocks. The sun shows the time of day and fixes the moment of noon, the stars show the changes of the seasons. Our pulse measures shorter time-spans, of the order of seconds.

Galileo discovered the pendulum effect in 1582, observing a chandelier in Pisa cathedral, but the first pendulum clock was not built until 1656. So Galileo’s observations were timed against his own pulse – there was no more accurate clock.

For his experiments on gravity in 1607, Galileo had to time a ball rolling down an inclined plane to an accuracy of fractions of a second. This was far beyond the capabilities of any period clock, and required finer gradations than a pulse-beat. The solution was found in the precision of musical rhythm – if a minim is about one second, then semi-quavers define an eighth of a second.

You can try for yourself an on-line simulation of Galileo’s experiment, precision-timed by lute-music, here.

For most of us, our intuitive understanding of Time is based on Newton’s model of Absolute Time: Time itself continues ever-onward, independent of other variables. We we can measure the accuracy of a clock, or the daily changes in the precise time of solar noon, against the fixed scale of Newton’s Time. But Newton published in 1687, and it was many decades before his concepts gained general acceptance. In the year 1600, the accepted model of Time was Aristotle’s:

Time is a number of change/movement, in respect of before and after.

Without an Absolute scale to measure by, without the assurance that Time would march independently onwards, “change/movement” was required to create a “before and after” that would allow Time to be numbered. So musical Time, i.e. rhythm, was not only indicated by the hand-movement of the Tactus, it required such movement (at least as a concept) in order to exist at all. The movement of the cosmos, driven by the hand of God, not only measured time, but created it. Just as the heart-beat sustains life, so the steadiness of the musical Tactus was necessary for human health and indeed, for the preservation of the entire universe.

Read more about the philosophy of Time and musical Rhythm here.

Action!

The first character to appear in the first opera is Old Father Time, and his first words (repeated) are Il Tempo. Time is a crucial topic in this drama, understood within Platonic philosophy. The fleeting present moment is a moving image of Eternity, the point of contact between human life and infinite destiny, between earthly actions and the eternal struggle of Good and Evil.

There are two Greek words that we translate as ‘Time’ or in Italian, tempo. Chronological time, clock time, is Greek kronos, whereas kairos signifies the moment of opportunity. For a swordsman, kairos is the crucial instant of time when you must defend yourself to save your life, or when you might safely attack your opponent.

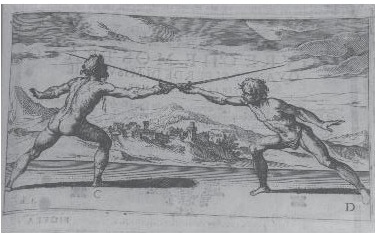

Monteverdi wrote a one-act opera entitled Combattimento, a music-drama of sword-fighting. Opera-singer Julie d’Aubigny, known as La Maupin, was the best duellist of her age. Many dancing-masters were also fencing instructors, and the anonymous sword-master of Bologna declared that swordsmen needed the same precision timing as singers!

Capo Ferro’s 1610 Gran Simulacrum teaches the Art of the Sword, as applied to the long, needle-point, razor-sharp Italian rapier. If your opponent points his sword at your heart, you turn your (right) sword-hand palm-up and leftwards, so that your sword crosses his and protects you. His likely response is to dip his sword-point underneath your blade, and threaten your right shoulder instead. Now you will have to turn your sword-hand palm down and rightwards, pushing his sword aside so that you can lunge forwards and strike with the point of your sword.

Act with the hand, act with the heart!

As we are told in the first scene of Anima & Corpo, historical acting linked emotional force to expressive hand-gestures. All the Action is founded on the poetic text, of course, as Shakespeare’s Hamlet instructs the Players:

Suit the Action to the Word

John Bulwer’s Chironomia (1644) shows gestures for Attention, for stylish Action, and for Antitheses (opposites): ‘on one hand…. on the other hand…’. Another way to Distinguish Contraries rotates the right hand palm-up and leftwards, then palm-down and out to the right.

We could imagine such gestures being performed in Shakespeare’s most famous line from Hamlet:

To be or not to be, that’s the question

First we Distinguish Contraries (to be, or not to be), and then we direct the audience’s Attention (the question). So To be (right hand palm-up and leftwards), or not to be (palm-down and out to the right), that’s (with index finger raised and the hand sent forwards, step forward to command the audience’s attention) the question.

If you try it for yourself, this sequence of movements might seem familiar to you: it is very similar to the sequence that we studied as a sword-drill, opposing to the left, turning the hand to close the line on the right, and then lunging forwards to strike.

Both Hamlet and Anima & Corpo are full of the language of sword-play. In Cavalieri’s masterpiece, the Guardian Angel would traditionally carry a sword, and the composer provides suitably martial music with G major harmonies and battle rhythms – the same harmonies and rhythms encountered a quarter-century later in Monteverdi’s Combattimento.

Like Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Cavalieri’s Anima & Corpo explores timeless questions of life and death by means of a fashionable vocabulary of sword-action. The English Play and the Italian Rappresentatione are each monuments of cultural achievement and artistic innovation: certainly not ‘primitive’, but endlessly fascinating and thought-provokingly different.

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our websites www.TheHarpConsort.com

www.IlCorago.com and www.TheFlow.Zone