aka “R_c_t_t_v_”

The theatrical style of Italian ‘new music’ c1600 is not loosely-written free rhythm. It is a precisely-notated imitation of rhetorical speech, specifically the spoken declamation of a fine actor, guided by the steady minim-beat of Tactus. [Peri 1600, Corago c1630].

This article summarises a 2025 view of Historical Performance Practice of ‘recitative’ in the first ‘operas’, citing period sources and with links to more detailed information. This topic has benefitted from significant recent research findings that might not yet have filtered through to Early Music practitioners: information trickles down even more slowly to theatrical performers.

So I apologise for re-stating what may be obvious to some readers. And I warmly welcome any corrections or comments from on-going research projects that I may not have seen.

The statements below are in-context citations from primary sources, concepts that I have tried and tested in real-life 21st-century ‘opera’ productions. There are links to articles examining complete texts of important sources.

Any secondary comments are identified as such. I also include short mnemonics or coaching mottos, frequently required in modern-day rehearsals.

Terminology

It is difficult to know what to call the stuff that the first ‘operas’ were mostly made on. Even the word opera itself was not yet applied in this context.

The English word recitative is unhelpful, being heavily loaded with 18th-century practices, not to mention 19th– and 20th-century distortions of those practices. The phrase musica recitativa was little used in early seicento Italy (the usual terms were derived from rappresentatione – a theatrical show. Monteverdi’s Orfeo was favola in musica, a story in music). Read more:

Then as now, recitare means ‘to act’. And ‘acted music’ musica recitativa, ‘show style’ (genere rappresentativo), theatrical solo music included a wide variety of diegetic songs, as well as the representation of speech and dialogue.

Read more about genres, sub-categories and why we should not call it ‘recitative’:

Italian Sources 1600-1640

This article summarises period information on performance practice for dramatic monodies that are not song-like [Doni 1640], charting the common consensus in Italian sources from the first ‘operas’ [c1600] to the anonymous guide to musical theatre for an artistic director Il Corago [c1630].

Let the reader beware: although there is strong consensus amongst primary sources, standard modern-day practice is rather different!

Priorities

Music is text and rhythm, with sound last of all. And not the other way around! [Caccini 1601]

The Rhetorical aim muovere gli affetti (to move the passions) is more highly valued than merely dilettare, delighting or ‘tickling the ears’. [Caccini 1601, Striggio 1607, Corago c1630 etc]

Sound

Voice-production is less ‘sung’, almost speech-like. [Peri 1600, Caccini 1601]

There is considerable difference between Good and Bad syllables. Unimportant syllables are passed over so lightly, that one cannot really determine their pitch [Peri 1600].

There are large contrasts in tone-quality for emotional effect. Singers can learn this from actors/story-tellers [Corago c1630].

The singer’s rhythms and pitches imitate the delivery of a fine actor in the spoken theatre [Peri 1600, Corago c1630]. Not modern-day conversational Italian, but a historical, stylised, rhetorical delivery suitable for a hall seating up to a thousand, without amplification or supertitles, with actors representing idealised pastoral poets, passionate lovers, gods and other super-heroes. Try speaking aloud in such a hall, to discover how it works.

Amidst this speech-like delivery, the penultimate syllable of each phrase (i.e. the last Good syllable, the Principal Accent of the line of poetry) is sustained and really sung, in sharp contrast to the final, Bad syllable which is especially short and light [Doni Annotazioni 1640 page 362].

The final note of each phrase is conventionally written long, but it is barely pronounced. This leaves time for gesture [Cavalieri 1600] or stage movement [Gagliano 1608]. But the final syllable should not be dropped entirely (as it sometimes is in everyday speech) [Corago c1630].

Last note unaccented and short [ALK c1990]

The greatest emotional effect is produced by crescendo or decrescendo on a single note [Caccini 1601]. To understand how this works, try it in spoken delivery.

Ornamentation

Ornamentation is generally discouraged [all sources] for singers and continuo alike.

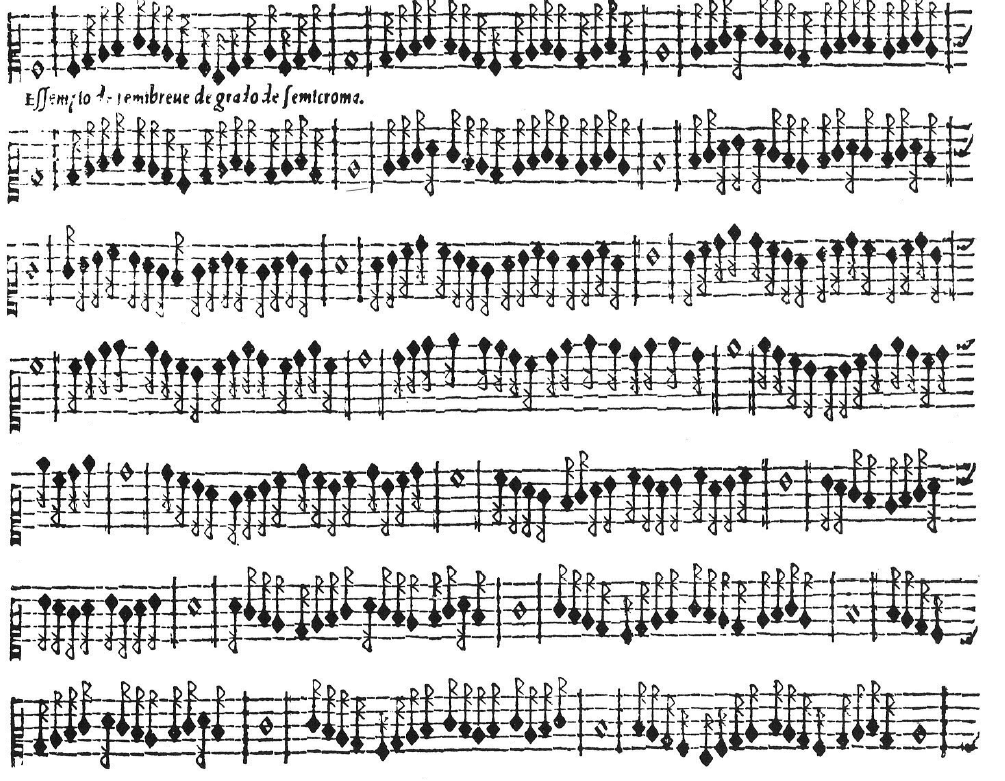

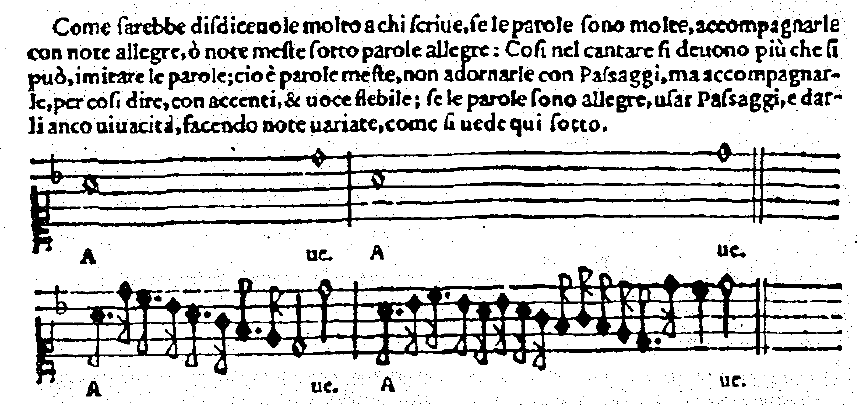

In particular, passaggi are not allowed in theatrical style because whilst they charm the ear, they do not move the passions. They are impressive, but not emotional. [Cavalieri 1600, Peri 1600, Corago c1630 etc].

That notorious ornament of the descending second ‘tenor cadence’ (up a fourth and down again) popular in the 1980s is no longer acceptable in polite society!

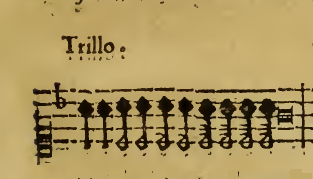

Even Caccini’s [1601] effetti (the single-note trillo, ‘beating in the throat’ double upper-note zimbelo, trill-and-turn gruppo) are used very sparingly: for the protagonist just three or four times in the entire opera, for supporting roles less [Cavalieri 1600].

I don’t know from whence came the current (2020s) fashion for a single upper-note flip (half a zimbelo?) on a minim-duration penultimate note, but it is far too frequently applied, judged by the rarity of the historical (double-flip) zimbelo or any other cadential ornament in period sources.

Doni’s recipe for the penultimate note is to sing it out, sustained and passionate.

Read more here:

Vibrato

In contrast to modern-day debates, vibrato is hardly mentioned in primary sources about ‘opera’ . As an ornament, it would be added in this style infrequently, towards the end of long notes.

Check whether your vibrato is appropriate by trying it in spoken delivery…

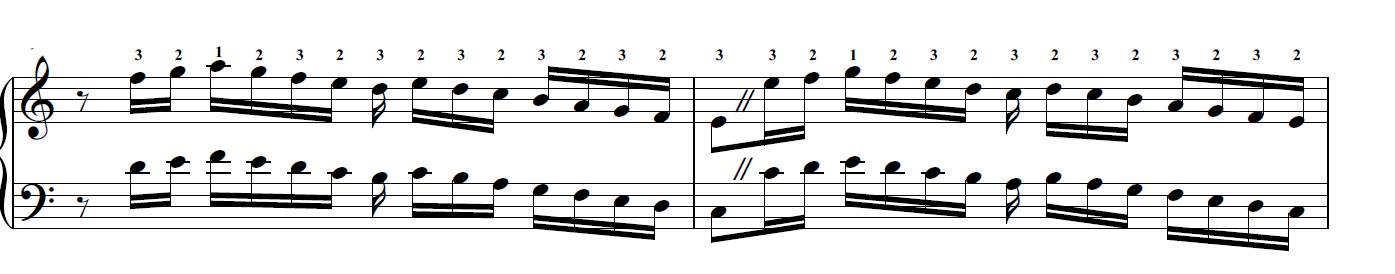

Passaggi

The following remarks are beyond the principal focus of this article, referring as they do to song-like solos.

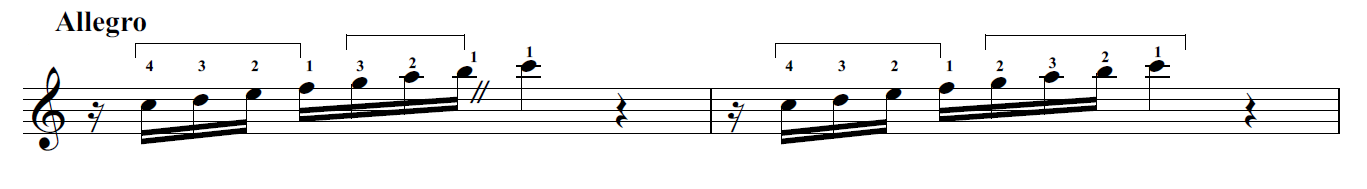

Passaggi – although forbidden in speech-like solos – are appropriate for Arias and diegetic Songs. [Monteverdi 1624/1638, Corago c1630, Doni 1640]. In this context, they are applied in the middle of the phrase, and not to the penultimate note, which is sustained plain, or (infrequently) with an effetto. [Caccini 1601, Monteverdi 1609, 1610]

An aria passeggiata (e.g. Possente spirto in Monteverdi’s Orfeo) can certainly be taken with a slower Tactus (Banchieri 1605 “Signor Organista will wait”). That Tactus should then be maintained steadily.

Contrary to some modern-day opinions, period sources emphasise the important of steady (albeit slower) Tactus in passaggi. Frescobaldi (1615a) reminds us not to start so fast that we have to slow down for the difficult bits later on!

Read more here, keeping in mind that in theatrical music, passaggi are only for those occasional song-like moments, not for the main bulk of speech-like delivery.

Rhythm

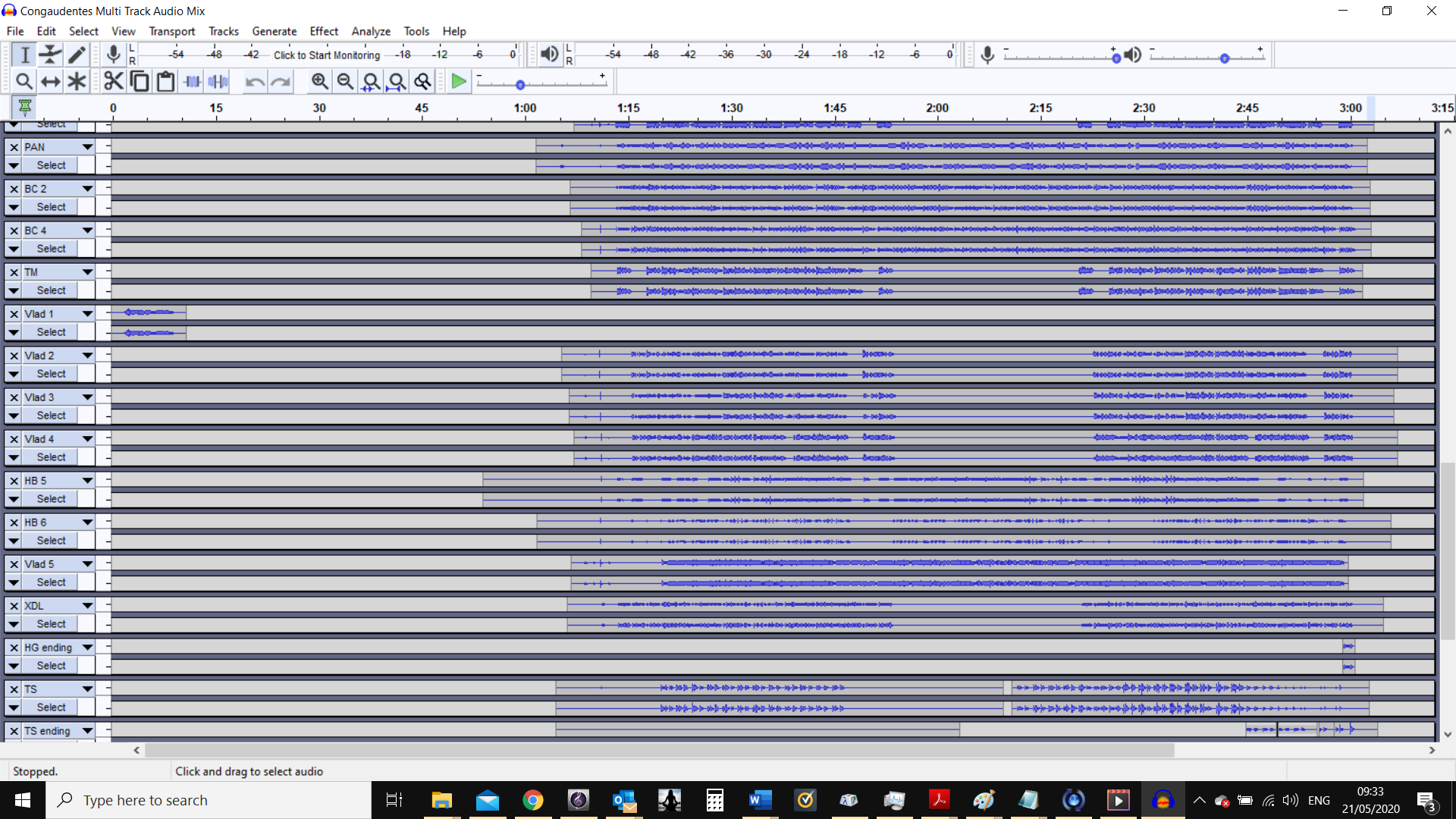

Baroque rhythm is controlled by Tactus, a slow steady beat. Before the year 1800, there was no “conducting” as we understand it today, only Tactus-beating.

Tactus was compared to clockwork [Zacconi 1596], but was not measured by machine. Rather it was kept as accurately as humanly possible. The performer’s task was not to invent some personal interpretation, but rather to find and maintain the correct Tactus as accurately as possible.

Constant Tactus

In principle, Tactus is constant throughout a piece, a whole work, even an entire repertoire. In practice, it might change slightly according to circumstances (e.g. different acoustics), individual perceptions (how accurately can you recall a specific beat?), composers’ directions, or certain conventions of performer intervention (see below).

Tactus is regular, solid, stable, firm… clear, sure, fearless, and without any perturbation whatsoever. [Zacconi 1596]

Compare this to modern conducting…

Tactus (tatto a light touch) is identical to beat (battuta), measure (misura, note-values adding up to one Tactus-unit of rhythmic notation) and tempo (Time itself). [Zacconi 1596].

This is an unfamiliar concept for modern-day musicians. Seicento musical tempo is not the ‘speed’ of the music measured against Newton’s [1687] Absolute Time. Rather tempo, notated rhythms and the Tactus beat are identical aspects of Time itself, described by Aristotle [4th cent. BC] as created by Motion (the Tactus beat).

Watch this video about pre-Newtonian Time:

Aristotle’s time requires an Observer with a Soul – in this context, a musician. (Compare Schrödinger’s Cat). Many sources characterise Tactus as ‘the Soul of Music’ [Zacconi 1596]. Read more here:

Grant [2014] explains this as the “calibration” of musical notation and performance to real-world time. In theatrical solos written under the mensuration sign C (looks like modern-day common time) a minim’s worth of written music corresponds to one second of real-world time [Mersenne 1636], shown by the downbeat of the Tactus hand.

The next minim’s worth, another one second of time, is shown by the upbeat. Down-and-up corresponds to a semibreve, the fundamental two-second unit.

These seconds of time are not measured by machine, but are maintained as accurately as humanly possible, based on long experience from elementary training and throughout a musician’s career. The subjective feeling of constancy will inevitably be modified by external factors (acoustic, size of ensemble) and by individual psychology (mood, emotion, performance excitement).

It is not a problem if a certain Tactus-beater remembers the feeling of the one-second beat slightly differently. But to misunderstand the rhythmic notation would be disastrous! [Zacconi 1596]. And all this – especially the underlying concept that musical Tactus is Time itself – is very different from the modern-day notion of a conductor or singer choosing their own speed.

Just imagine: “Sorry I’m late for rehearsal, I thought my personal interpretation of 10am would be more expressive than everyone else’s way.” No, the task is to get it right, as best one humanly can.

According to the ancient doctrine of the Music of the Spheres, earthly music-making imitates the perfect music of the cosmos, mirrored in microcosm by the harmonious nature of the human being.

If your pulse stops, the music also dies. ALK (c2010)

Typically, Tactus-beating consists precisely of this simple, regular down-up movement, quite different from modern conducting. Since instrumentalists’ hands are already busy, Tactus was often administered by singers. Instrumentalists could use their feet. Tactus-beating was applied even in lute-song duos, but the Tactus-beater might not be visible to ensemble colleagues. (Compare jazz backing-singers clicking their fingers at the back of a Big Band).

In principle, even a full-length work would have the same steady down-and-up all the way through. [Corago c1630]

No conducting!

In practice, there was no Tactus-beating in theatrical music [Monteverdi 1619, Corago c1630]. Theatricality would be destroyed by singers on stage beating time when they were supposed to be representing dramatic characters; the audience would be distracted by the constant beat amongst the instrumentalists. However, the principal continuo player might give the start signal for an ensemble chorus. [Corago c1630]

The modern-day practice of a conductor using a harpsichord as an expensive music-stand is not supported by period evidence. [ALK c2020]

Tweaking the Tactus

Whilst most musical genres were subject to a fixed Tactus throughout, fashionable seicento compositions with passionate vocal effects and contrasting movements – toccatas and madrigals are specified, we can safely assume ‘opera’ too – were controlled and facilitated by a Tactus that could vary slightly, in specific situations [Frescobaldi 1615].

Each movement proceeds in regular Tactus, but when a movement ends with a formal cadence and the next movement has a contrasting passo (rhythmic structure, literally a pace or a dance-step, a metrical ‘foot’ in poetry) the Tactus can hesitate on the upstroke and restart slower or faster. Read more here:

Marincic [2019] cites many, many sources supporting the notion of ‘now quickly, now again slowly’.

https://ojs.zrc-sazu.si/dmd/article/download/7665/7217/20092

Tactus-contrasts are linked to contrasts in musical activity, and to contrasting affekts. In early 17th-century music, these contrasts all work in the same direction. An agitated text will be set with shorter note-values, performed with a faster Tactus. This creates practical speed-limits: the extreme agitation of Monteverdi’s Combattimento is set with a syllable on each semiquaver: these notorious tongue-twisters can be performed only slightly faster than minim = 60. Read much more from Marincic, Dokter, Wentz et al. here:

Contrasts within steady Tactus

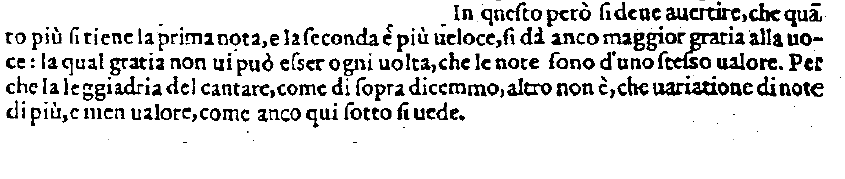

Even when note-values are equal, good delivery of poetry requires contrast between Good and Bad syllables, also described as Long and Short [Caccini 1601].

As the intensity of passion rises, seicento composers write increasing contrasts of note-values.

The performer can alter note-values to achieve ‘more grace’. These alterations – within the steady Tactus – lead consistently to greater contrast between long and short note-values. [Caccini 1601]

Of course, it is demanding to deliver, even exaggerate, contrasting note-values within steady Tactus. But this is the secret of gratia and leggiadria. [Caccini 1601, Bovicelli 1594]. Learning how to do this in the ‘opera’ at hand is what rehearsal is for [Corago c1630].

Long notes long, short notes short. [ALK c2010]

Word-accents and Tactus

Good syllables often coincide with the Tactus beat, but not always. Tactus is a measure of Time, not an indication of accentuation. See Time, the Soul of Music and The Good, the Bad… (above).

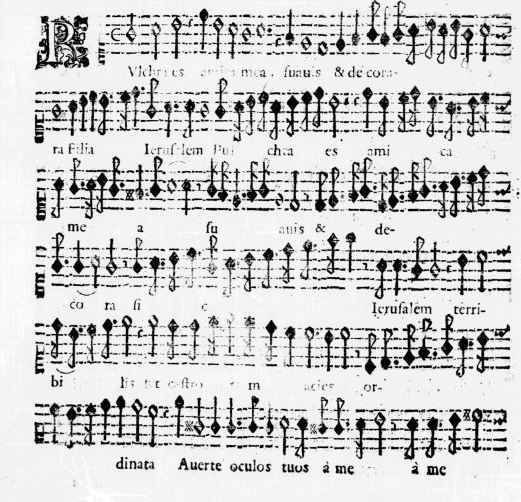

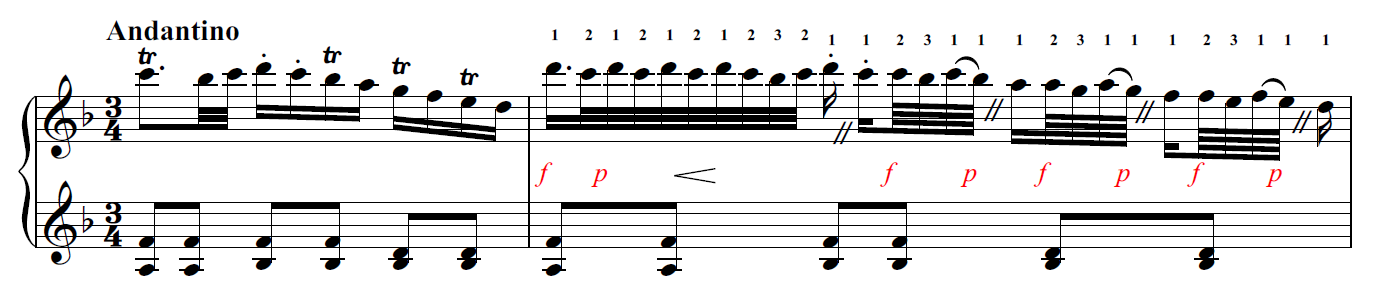

The principle of avoiding ‘the tyranny of the downbeat’ familiar to us in renaissance polyphony still applies in early baroque monody. In dramatic monody as in polyphonic madrigals, singers’ parts are usually written without barlines. Barlines in tablatures and continuo short-scores are merely an aid to players’ understanding of vertical alignment. If there is barring in theatrical music, it is usually irregular.

Poetic accents, Good syllables, placed by the composer off the Tactus beat create a dramatic impression that something is wrong. Thus the opening of Act I of Monteverdi’s Orfeo (above) subtly undercuts the sung text with dramatic irony: ‘this happy and fortunate day’ may not be so lieto (happy, but off the beat) after all. The Shepherd doesn’t know, but the audience gets the message of Monteverdi’s subtext.

Who follows whom?

The continuo-instruments guide and direct the whole ensemble of instruments and voices. [Agazzari 1607].

Continuo directs ‘opera’ singers [Gagliano 1608, Corago c1630]. Difficult moments should be rehearsed repeatedly. But if – even after diligent rehearsal – something goes wrong in performance, Continuo-players should rescue the situation. [Corago c1630].

To make the music more beautiful, singers can always deliver an accented syllable late. The delay can be as much as a quarter-note (half a second). This applies to soft, gentle affekts, strong or aggressive words should not be delayed. But Tactus is maintained, it does not give way to the singer, who must re-unite with the Tactus within a couple of beats. [Zacconi 1596]

I call this the Ella Fitzgerald rule. It’s a like a slow ballad in jazz. Singers can sing off the beat, but they know where the beat is, the continuo (rhythm section) maintain the steady swing, and everyone joins up again after a while. Read more here:

Monteverdi often notates deliberate misalignment between soloist and continuo, showing how this “Ella Fitzgerald rule” works in practice, e.g. the opening of Nigra sum from the [1610] Vespers.

Free solo-singing over steady Tactus is probably what Caccini [1601] means by “senza misura – unmeasured – almost speaking with the previously mentioned sprezzatura – ‘cool’”. That previous mention of sprezzatura unambiguously refers to ‘cool’ voice-production: not fully ‘sung’, almost like speaking. More about sprezzatura here:

But there is a later, instrumental practice of senza misura (e.g.Froberger Lamentation). See Time, the Soul of Music (above). And an early seicento vocal notation of many syllables under a single long note-value, like chanting a psalm [Monteverdi 1610, psalm settings; and 1603, madrigal Sfogava; Landi 1619, an operatic lament].

So Caccini’s senza misura might possibly involve a temporary suspension of the Tactus beat. But, contrary to the “Ella Fitzgerald rule” which Zacconi says can always apply, actual senza misura is extremely rare. If Caccini applies it at all, it is only once in his whole book, for the duration of a few notated Tactus-units, and in response to an obvious prompt in the text.

See also

and

Both the above articles were written before I found Zacconi’s description of the Ella Fitzgerald rule.

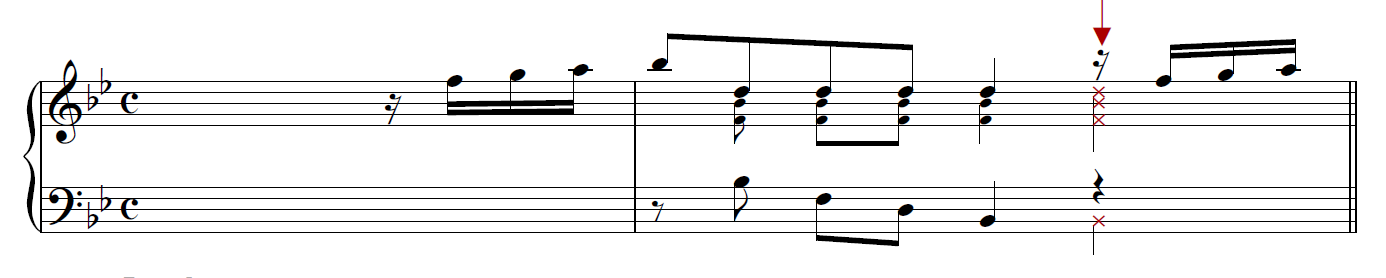

Dramatic pauses

Where stage action requires a pause, the continuo should maintain Tactus until the singer is ready. They do this by repeating a single chord, or (if it’s known in advance that more time is needed) a chord-sequence. [Corago c1630]. This practice of “vamp till ready” is described by Cavalieri [1600] and notated in Monteverdi’s Ulisse [c1640].

In Monteverdi’s Lamento della Ninfa [1623/1638], the soloist sings “in the time of the affection of the spirit, and not in that of the hand”. This is not about rubato, we know from Zacconi that singers can always deliver a note late, but the Tactus (the time of the hand) does not waver. This is about taking extra time for an emotional pause. In this piece, whenever the affetto encourages the soloist to take extra time before an entry, the continuo can fill in with an extra repeat of the ground bass. Read more here:

Text

Singers should “chisel out the syllables” [Gagliano 1608]. In addition to correct pronunciation of vowels and consonants, contrasts should be clearly shown between Good and Bad syllables, also termed Long and Short [Caccini 1601]. Also single and double consonants.

Non-native speakers should be careful not to accent syllables by emphasising the initial consonant: they should rather give additional intensity and length to the vowel. English speakers should be careful not to signal emotion by elongating consonants (this is a serious fault in Italian pronunciation): they should rather prolong and add intensity to the vowel.

Singers should respond to contrasting affekts word by word [Monteverdi, letter to Striggio 1627]. Opposite affekts are often placed in close proximity [Cavalieri 1600].

A speech beginning with many syllables on a single note is a code for narration: let me tell you a story. [Doni 1640]

Prologues and gods may have a more solemn style with longer notes and more ‘singing’. [Doni 1640, Corago c1630]

The soft hexachord (with Bb) corresponds to softer affekts, the hard hexachord (with B natural) to harsher affekts.

Vocal pitches and rhythms imitate the declamation of an actor in the spoken theatre [Peri 1600, Corago c1630]. To understand how this works, try speaking the line, as if on stage in a big theatre, and bringing your pitch-contours and rhythms as close as possible towards the composer’s notation. You can assess the level of emotional intensity by seeing how much passion is needed to speak at the composer’s notated pitch-level.

Continuo

The continuo’s role is not to follow the singers (and certainly not to follow a conductor), but to support and guide by maintaining steady Tactus. [Gagliano 1608, Corago c1630].

Maintain Tactus even if the singer chooses to be off the beat, temporarily [Zacconi 1596, aka ‘the Ella Fitzgerald rule’].

The continuo should imitate the sound and the emotional meaning of the words [Agazzari 1607].

The emotional character of a speech is determined by the rhythms and harmonies of the bass. Sad or serious matters have the bass in long notes (minims, semibreves). In happy or lighter mood, short notes in the bass encourage the singer’s delivery to ‘dance’. [Peri 1600].

The realisation should not sub-divide the written note-values [Cavalieri 1600 etc]. This is both the usual prohibition against passaggi and also an instruction to preserve the written note-values of the bass, which determine the emotional character.

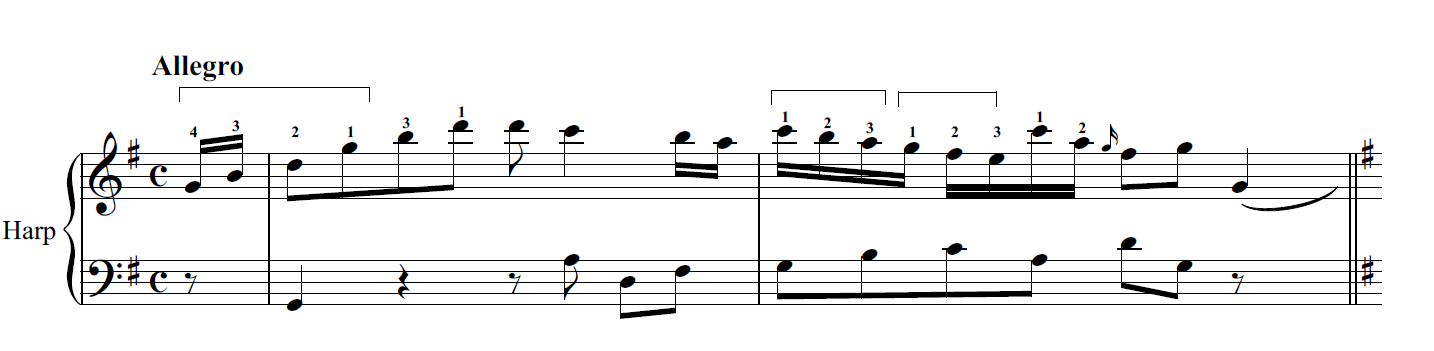

Organ, harpsichord, lirone, violone etc play fundamental realisations in long notes. Harps, theorbos etc play faster-moving bass-lines. [Agazzari 1607, Landi 1631].

Correct movement of inner voices is not important [Caccini 1601]. This is a warning against over-elaborate harmonies or over-polyphonic realisations: best practice is to play simple harmonies in homophonic chords vertically over the bass.

Use mostly root-position chords, change for 6 only according where the rules specify (later repertoires use 6 chords much more). Early seicento harmonies are bold and simple, and often a more active vocal line clashes against slow-moving continuo harmonies. [Peri 1600, Cavalieri 1600].

There is considerable evidence to suggest that the continuo was balanced to be softer to the audience’s ears than we hear in modern-day performances.

Similarly to the changes Frescobaldi describes for Tactus, continuo-scoring can change between sections that have emotional contrasts and different rhythmic structures. [Monteverdi 1609]

Continuo-players direct by playing clear rhythms, not by waving their hands. [Corago c1630].

A harpsichord is not an expensive music-stand for a wannabe conductor [ALK 2025].

Bowed melodic bass instruments usually do NOT play in speech-like music, and/or where the bass-line is not melodic. [Monteverdi 1609] Bass wind-instruments are extremely rare in this genre [Agazzari 1607].

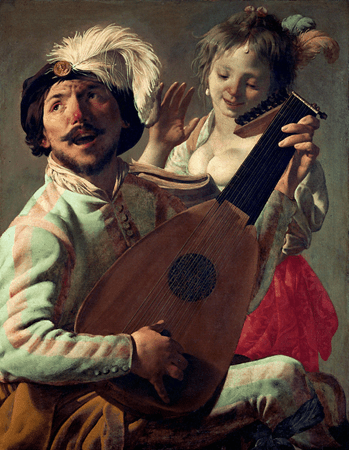

The most common accompaniment is theorbo and organ [Monteverdi 1609 for opera], theorbo alone [Caccini 1601, for chamber songs], harp alone [Agazzari 1607 for small ensembles], organ alone [Viadana 1602 for church music, Monteverdi 1609 for special operatic moments].

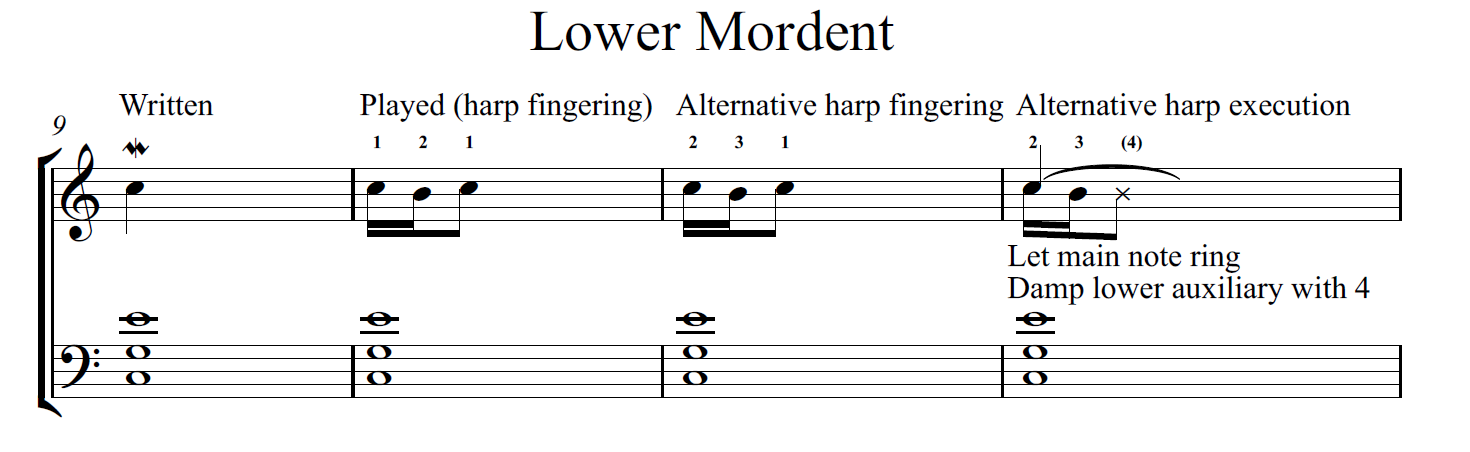

Arpeggios start on the beat, not before. [Kapsberger 1604, Frescobaldi 1615, Piccinini 1623, etc etc] See also Agazzari’s [1607] warnings about ‘soup and confusion’.

Larger continuo ensembles are associated with concerted ensemble music. [Agazzari 1607, Monteverdi 1609, Landi 1631].

There is evidence for string consort accompaniment as an unusual special effect, written in by the composer [Monteverdi Combattimento 1624/1638. Also Arianna 1608 according to eye-witness accounts, but the string-parts do not survive]. Whilst string-ritornelli sometimes have to be supplied for Arias (e.g Cavailli, where upper strings are obviously required, but their parts don’t always survive), there is no justification for adding string accompaniments generally, and especially not to speeches.

As a rule of thumb, take treble A (‘tuning A’, 440, 465 Hz whatever) as the highest note for your realisations. Staying underneath the voice part often works well, doubling a simplified version of the voice part can work for organ, less well for plucked instruments. [ALK]

Gesture

Although the modern-day term is Baroque Gesture, period sources discuss full-body acting, including how and when to walk, facial expressions etc as well as hand gestures. [Cavalieri 1600, Monteverdi 1608, Gagliano 1608].

Gestures support the meaning, emotion and rhetoric of the text and are timed with the text. [Monteverdi 1624/1638, etc etc]

Gestures can look very beautiful, but should not be reduced to a ‘ballet of the hands’. They should support the text and help move the audience’s passions. A good rule of thumb is that if the audience become aware of your gesturing, you are doing it wrong!

Final notes (notated long but performed short) provide time for gesture between one phrase and the next. [Cavalieri 1600]

Similarly, the last note of a speech can be used to change position on the stage, for example in dialogues. This movement begins on the penultimate note (i.e. the last Good syllable) already. [Gagliano 1608]

Read more about Gesture and Historical Action:

There is a modern-day trend to link the period practice of physical, rhetorical gestures with what today’s practitioners call ‘musical gesture’. In standard Music Psychology, Musical Gesture refers to body movements made by performers, but in Early Music it describes the concept that particular melodic fragments might be played in a way that goes beyond the literal notation to create powerful emotional effect.

Such transformations are clearly described by Caccini [1601], placed in the context of underlying Tactus and consistently in the direction of exaggerating contrasts in written note-values. Certain fragments found in toccatas and early sonatas are similar to the effetti, vocal ornaments for emotional effect, described by Cavalieri [1600], Caccini [1601] and others.

But I am sceptical about any significant historical link between these effetti and rhetorical (i.e. text-based) hand-gestures. At worst, the whole concept might be just an excuse for modern players’ bad rhythm!

Conclusion

This article has set out technical information passed down to us from primary sources, how to perform speech-like dramatic monody by focussing on Text and Tactus.

The purpose of this style is not to tickle the ear, but to move the audience’s passions. Read more here:

The study of Historical Performance Practice is a fast-moving field. Much of what we thought was ‘authentic’ in the 1980s has been challenged by recent research. The conclusions I draw in this article will no doubt be revised in years to come, but I hope the collected citations will remain relevant and useful to readers and performers.

I give the last word to Monteverdi’s Shepherd (see above), as his ‘spoken’ words exhort the chorus to sing:

Let’s sing in such sweet turns of phrase, that our ensembles may be worthy of Orpheus! [Striggio, 1607]

R*C*T*T*V* 2025

Speech-like solos in early ‘opera’.

Terminology

It is difficult to know what to call the stuff that the first ‘operas’ were mostly made on. Even the word ‘opera’ itself was not yet applied in this context.

The English word recitative is heavily loaded with 18th-century practices, not to mention 19th– and 20th-century distortions of those practices. The phrase musica recitativa was little used in early seicento Italy (the usual terms were derived from rappresentatione – a theatrical show. Monteverdi’s Orfeo was favola in musica, a story in music).

Then as now, recitare means ‘to act’. And this ‘music for acting’, this ‘show style’ (genere rappresentativo), this theatrical solo music included a wide variety of diegetic songs, as well as the representation of speech and dialogue.

Read more about genres, sub-categories and why we should not call it ‘recitative’:

Italian Sources 1600-1630

This article updates performance practice information for dramatic monodies that are not song-like [Doni 1640], charting the common consensus in Italian sources from the first ‘operas’ [c1600] to the anonymous guide to musical theatre for an artistic director Il Corago [c1630].

Although there is strong consensus amongst primary sources, standard modern-day practice is rather different!

The ‘new music’ c1600 is not loosely written free rhythm. It is a precisely notated imitation of the spoken declamation of a fine actor, guided by the steady minim-beat of Tactus. [Peri 1600, Corago c1630].

Priorities

Music is text and rhythm, with sound last of all. And not the other way around! [Caccini 1601].

The Rhetorical aim muovere gli affetti (to move the passions) is more highly valued than merely delighting (dilettare) or ‘tickling the ears’. [Caccini 1601, Corago c1630 etc etc]

Sound

Voice-production is less ‘sung’, almost speech-like. [Peri 1600, Caccini 1601]

There is considerable difference between Good and Bad syllables, such that unimportant syllables are passed over so lightly one cannot really determine their pitch [Peri 1600].

See https://andrewlawrenceking.com/2013/09/22/the-good-the-bad-the-early-music-phrase/

There are large contrasts in tone-quality for emotional effect. Singers can learn this from actors/story-tellers [Corago c1630].

The singer’s rhythms and pitches imitate the delivery of a fine actor in the spoken theatre [Peri 1600, Corago c1630]. Not modern-day conversational Italian, but a historical, stylised, rhetorical delivery suitable for a hall seating up to a thousand, without amplification or supertitles, with actors representing idealised pastoral poets, passionate lovers, gods and other super-heroes. Try speaking aloud in such a hall, to discover how it works.

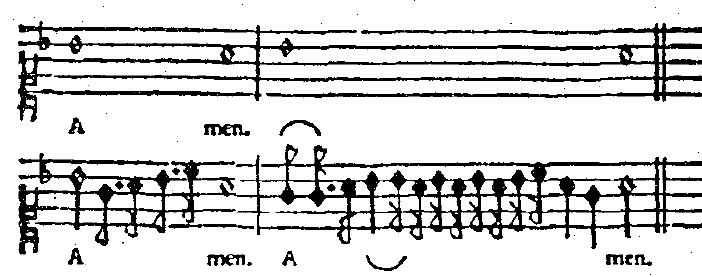

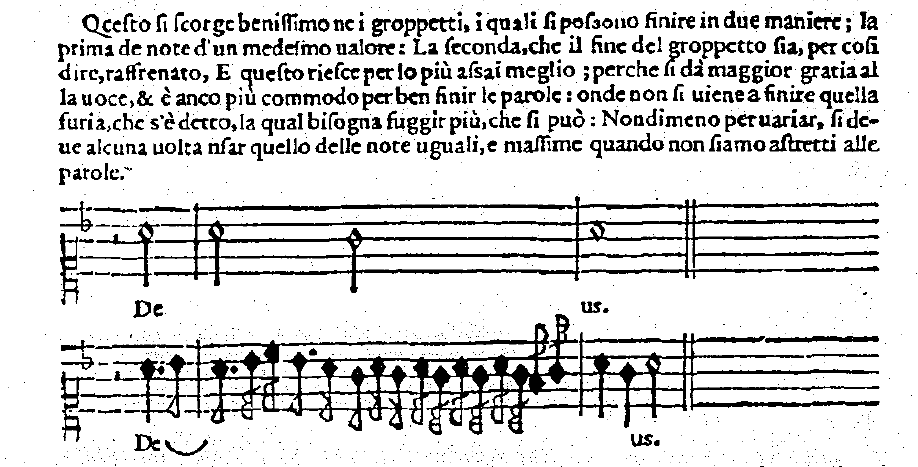

Amidst this speech-like delivery, the penultimate syllable (which will be Good, the principal accent of the line of poetry) of each phrase is sustained and sung, in sharp contrast to the final, Bad syllable which is especially short and light [Doni Annotazioni 1640 page 362].

The final note of each phrase is conventionally written long, but it is barely pronounced. This leaves time for gesture [Cavalieri 1600] or stage movement [Gagliano 1608]. But the final syllable should not be dropped entirely (as it sometimes is in everyday speech) [Corago c1630].

The greatest emotional effect is produced by crescendo or decrescendo on a single note [Caccini 1601]. To understand how this works, try it in spoken delivery.

Ornamentation

Ornamentation is generally discouraged [all sources] for singers and continuo alike.

In particular, passaggi are not allowed in theatrical style because whilst they charm the ear, they do not move the passions. They are impressive, but not emotional. [Cavalieri 1600, Peri 1600, Corago c1630 etc].

That notorious ornament of the tenor cadence (up a fourth and down again) is no longer acceptable in polite society!

Even Caccini’s [1601] affetti (the single-note trillo, ‘beating in the throat’ double upper-note zimbelo, trill-and-turn gruppo) are used very sparingly: for the protagonist just three or four times in the entire opera, for supporting roles less [Cavalieri 1600].

The current fashion for half a zimbelo on the penultimate note is inaccurate and heavily overdone, compared to the rarity of the historical (double-beat) zimbelo or any other ornament in period sources.

Doni’s recipe for the penultimate note is to sing it out, sustained and passionate.

Read more here:

Vibrato

In contrast to modern-day debates, vibrato is hardly mentioned in primary sources. As an ornament, it would be added infrequently, towards the end of long notes. Check whether your vibrato is appropriate by trying it in spoken delivery…

Passaggi

The following remarks are strictly beyond the scope of this article, referring as they do to song-like solos.

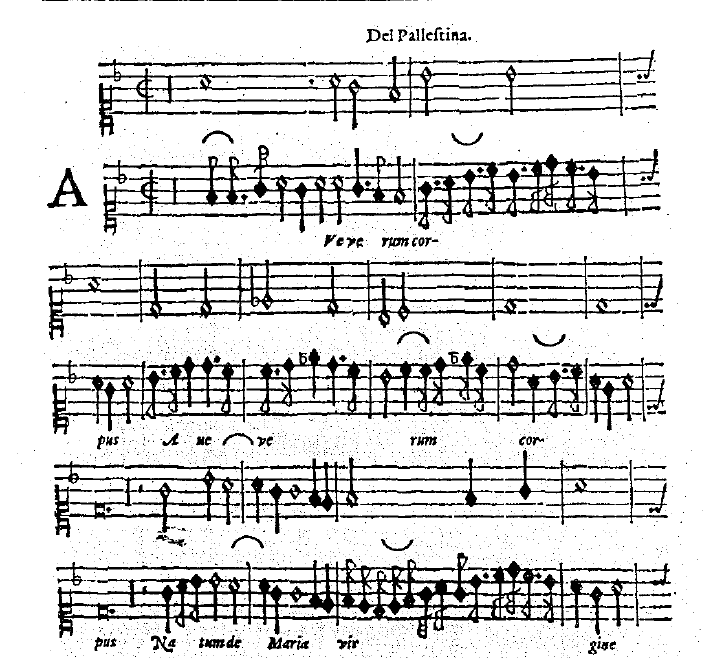

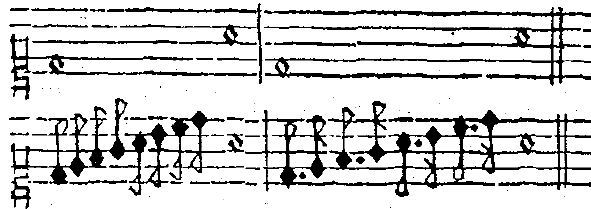

Passaggi – although forbidden in speech-like solos – are appropriate for Arias and diegetic Songs. [Monteverdi 1624/1638, Corago c1630, Doni 1640]. In this context, they are applied in the middle of the phrase, but not to the penultimate note, which is sustained plain, or (infrequently) with an affetto. [Caccini 1601, Monteverdi 1609, 1610]

An aria passeggiata (e.g. Possente spirto in Monteverdi’s Orfeo) can certainly be taken with a slower Tactus (Banchieri 1605 “Signor Organista will wait”). That Tactus should then be maintained steadily. Read more here:

Rhythm

Baroque rhythm is controlled by Tactus, a slow steady beat. Before the year 1800, there was no “conducting” as we understand it today, only Tactus-beating.

Tactus was compared to clockwork [Zacconi 1596], but was not measured by machine. Rather it was kept as accurately as humanly possible. The performer’s task was not to invent some personal interpretation, but rather to find and maintain the correct Tactus as accurately as possible.

Constant Tactus

In principle, Tactus is constant throughout a piece, a whole work, even an entire repertoire. In practice, it might change slightly according to circumstances (e.g. different acoustics), individual perceptions (how accurately can you recall a specific beat?), composers’ directions, or certain conventions of performer intervention (see below).

Tactus is regular, solid, stable, firm… clear, sure, fearless, and without any perturbation whatsoever. [Zacconi 1596] Compare this to modern conducting…

Tactus (tatto a light touch) is identical to beat (battuta), measure (misura note-values adding up to one unit of rhythmic notation) and tempo (Time itself). [Zacconi 1596].

This is an unfamiliar concept for modern-day musicians. Seicento musical tempo is not the ‘speed’ of the music measured against Newton’s [1687] Absolute Time. Rather tempo, notated rhythms and the Tactus beat are identical aspects of Time itself, described by Aristotle [4th cent. BC] as created by Motion (the Tactus beat) and requiring an Observer with a Soul – in this context, a musician. (Compare Schrödinger’s Cat). Many sources characterise Tactus as ‘the Soul of Music’ [Zacconi 1596]. Read more here:

https://andrewlawrenceking.com/2020/03/29/time-the-soul-of-music/

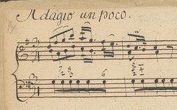

Grant [2014] explains this as the “calibration” of musical notation and performance to real-world time. In theatrical solos written under the mensuration sign C (looks like modern-day common time) a minim’s worth of written music corresponds to one second of real-world time [Mersenne 1636], shown by the downbeat of the Tactus hand. The next minim’s worth, another one second of time, is shown by the upbeat. Down-and-up corresponds to a semibreve, the fundamental unit.

Typically, Tactus-beating consists precisely of this simple, regular down-up movement, quite different from modern conducting. Since instrumentalists’ hands are already busy, Tactus was often administered by singers. Instrumentalists could use their foot. Tactus-beating was applied even in lute-song duos, but the Tactus-beater might not be visible to ensemble colleagues. (Compare jazz backing-singers clicking their fingers at the back of a Big Band). In principle, even a full-length work would have the same steady down-and-up all the way through. [Corago c1630]

No conducting

In practice, there was no Tactus-beating in theatrical music [Corago c1630]. Theatricality would be destroyed by singers beating time when they were supposed to be representing dramatic characters; the audience would be distracted by the constant beat amongst the instrumentalists. The principal continuo player might give the start signal for an ensemble chorus.

Tweaking the Tactus

Whilst most musical genres were subject to a fixed Tactus throughout, fashionable seicento compositions with passionate vocal effects and contrasting movements – toccatas and madrigals are specified, we can safely assume ‘opera’ too – were controlled and facilitated by a Tactus that could vary slightly, in specific situations [Frescobaldi 1615].

Each movement proceeds in regular Tactus, but when a movement ends with a formal cadence and the next movement has a contrasting passo (rhythmic structure, literally a pace or a dance-step, a metrical ‘foot’ in poetry) the Tactus can hesitate on the upstroke and restart slower or faster. Read more here: https://andrewlawrenceking.com/2015/10/23/frescobaldi-rules-ok/

Marincic [2019] cites many, many sources supporting the notion of ‘now quickly, now again slowly’.

Tactus-contrasts are linked to contrasts in musical activity, and to contrasting affekts. In early 17th-century music, these contrasts all work in the same direction. An agitated text will be set with shorter note-values, performed with a faster Tactus. This creates practical speed-limits: the extreme agitation of Monteverdi’s Combattimento is set with a syllable on each semiquaver: these notorious tongue-twisters can be performed only slightly faster than minim = 60. Read more here:

https://andrewlawrenceking.com/2021/05/05/looking-for-a-good-time/

Contrasts within steady Tactus

Even when note-values are equal, good delivery of poetry requires contrast between Good and Bad syllables, also described as Long and Short [Caccini 1601].

As the intensity of passion rises, seicento composers write increasing contrasts of note-values.

The performer can alter note-values to achieve ‘more grace’. These alterations – within the steady Tactus – lead consistently to greater contrast between long and short note-values. [Caccini 1601]

Word-accents and Tactus

Good syllables often coincide with the Tactus beat, but not always. The principle of avoiding ‘the tyranny of the downbeat’ familiar from renaissance polyphony still applies in early baroque monody. In dramatic monody as in polyphonic madrigals, singers’ parts are written without barlines: continuo short-scores have barlines to aid players’ understanding of vertical alignment. If there is barring, it is usually irregular.

Poetic accents placed off the Tactus beat create the impression that something is wrong. Thus the opening of Act I of Monteverdi’s Orfeo subtly undercuts the sung text with dramatic irony: ‘this happy and fortunate day’ may not be so lieto (happy, but off the beat) after all. The Shepherd doesn’t know, but the audience understands.

Who follows whom?

The continuo guide and direct the whole ensemble of instruments and voices. [Agazzari 1607].

Continuo directs the singers [Gagliano 1608, Corago c1630]. Difficult moments should be rehearsed repeatedly. But if – even after diligent rehearsal – something goes wrong in performance, Continuo-players should rescue the situation. [Corago c1630].

To make the music more beautiful, singers can always deliver an accented syllable late. The delay can be as much as a quarter-note (half a second). This applies to soft, gentle affekts, strong or aggressive words should not be delayed. But Tactus is maintained, it does not give way to the singer, who must re-unite with the Tactus within a couple of beats. [Zacconi 1596]

I call this the Ella Fitzgerald rule. It’s a like a slow ballad in jazz. Singers can sing off the beat, but they know where the beat is, the continuo (rhythm section) maintain the steady swing, and everyone joins up again after a while. Read more here:

https://andrewlawrenceking.com/2021/11/20/making-time-for-beautiful-singing-a-lost-practice/

Monteverdi often notates deliberate misalignment between soloist and continuo, showing how this “Ella Fitzgerald rule” works in practice, e.g. the opening of Nigra sum from the [1610] Vespers.

This free solo over steady Tactus is probably what Caccini [1601] means by “senza misura – unmeasured – almost speaking with the previously mentioned sprezzatura – ‘cool’”. That previous mention of sprezzatura unambiguously refers to ‘cool’ voice-production, not fully ‘sung’, almost like speaking.

But there is a later, instrumental practice of senza misura (e.g.Froberger Lamentation). And an early seicento vocal notation of many syllables under a single long note-value, like chanting a psalm [Monteverdi 1610, psalm settings; Landi 1619, an operatic lament].

So Caccini’s senza misura might possibly involve a temporary suspension of the Tactus beat. Note that he applies it only once in his whole book, for the duration of a few notated Tactus-units, and in response to an obvious prompt in the text. Contrary to the “Ella Fitzgerald rule” which Zacconi says can always apply, actual senza misura is extremely rare.

See also https://andrewlawrenceking.com/2015/10/12/monteverdi-caccini-jazz/

and https://andrewlawrenceking.com/2017/11/25/tactus-sprezzatura-drama/

both written before I found Zacconi’s description of the Ella Fitzgerald rule.

Dramatic pauses

Where stage action requires a pause, the continuo should maintain Tactus until the singer is ready. They do this by repeating a single chord, or (if it’s known in advance that more time is needed) a chord-sequence. [Corago c1630]. This practice of “vamp till ready” is described by Cavalieri [1600] and notated in Monteverdi’s Ulisse [c1640].

In Monteverdi’s Lamento della Ninfa [1623/1638], the soloist sings “in the time of the affection of the spirit, and not in that of the hand”. This is not about rubato, we know from Zacconi that singers can always deliver a note late, but the Tactus (the time of the hand) does not waver. This is about taking extra time for an emotional pause. In this piece, whenever the affetto encourages the soloist to take extra time before an entry, the continuo can fill in with an extra repeat of the ground bass. Read more here:

Text

Singers should “chisel out the syllables” [Gagliano 1608]. In addition to correct pronunciation of vowels and consonants, contrasts should be clearly shown between Good and Bad syllables, also termed Long and Short [Caccini 1601]. Also single and double consonants.

Non-native speakers should be careful not to accent syllables by emphasising the initial consonant: they should rather give additional intensity and length to the vowel. English speakers should be careful not to signal emotion by elongating consonants (this is a serious fault in Italian pronunciation): they should rather prolong and add intensity to the vowel.

Singers should respond to contrasting affekts word by word [Monteverdi, letter to Striggio 1627]. Opposite affekts are often placed in close proximity [Cavalieri 1600].

A speech beginning with many syllables on a single note is a code for narration: let me tell you a story. [Doni 1640]

Prologues and gods may have a more solemn style with longer notes and more ‘singing’. [Doni 1640, Corago c1630]

The soft hexachord (with Bb) corresponds to softer affekts, the hard hexachord (with B natural) to harsher affekts.

Vocal pitches and rhythms imitate the declamation of an actor in the spoken theatre [Peri 1600, Corago c1630]. To understand how this works, try speaking the line, as if on stage in a big theatre, and bringing your pitch-contours and rhythms as close as possible towards the composer’s notation. You can assess the level of emotional intensity by seeing how much passion is needed, in order to speak at the composer’s notated pitch-level.

Continuo

The continuo’s role is not to follow the singers (and certainly not to follow a conductor), but to support and guide by maintaining steady Tactus. [Gagliano 1608, Corago c1630]. If a singer is uncertain, there should be more rehearsal [Corago c1630].

Maintain Tactus even if the singer chooses to be off the beat, temporarily [Zacconi 1596, aka ‘the Ella Fitzgerald rule’].

The continuo should imitate the sound and the emotional meaning of the words [Agazzari 1607].

The emotional character of a speech is determined by the rhythms and harmonies of the bass. Sad or serious matters have the bass in long notes (minims, semibreves). In happy or lighter mood, short notes in the bass encourage the singer’s delivery to ‘dance’. [Peri 1600].

The realisation should not sub-divide the written note-values [Cavalieri 1600 etc]. This is both the usual prohibition against passaggi and also an instruction to preserve the written note-values of the bass, which determine the emotional character.

Organ, harpsichord, lirone, violone etc play fundamental realisations in long notes. Harps, theorbos etc play faster-moving bass-lines. [Agazzari 1607, Landi 1631].

Correct movement of inner voices is not important [Caccini 1601]. This is a warning against over-polyphonic realisations and over-elaborate re-harmonisations. Best practice is to play simple harmonies in homophonic chords vertically over the bass.

Early seicento harmonies are bold and simple, and often a more active vocal line clashes against slow-moving continuo harmonies. [Peri 1600, Cavalieri 1600].

There is considerable evidence to suggest that the continuo was balanced to be softer to the audience’s ears than we hear in modern-day performances.

Similarly to the changes Frescobaldi describes for Tactus, continuo-scoring can change between sections that have emotional contrasts and different rhythmic structures. [Monteverdi 1609]

Continuo-players direct by playing clear rhythms, not by waving their hands. [Corago c1630].

A harpsichord is not an expensive music-stand for a wannabe conductor [ALK 2025].

Bowed melodic bass instruments usually do NOT play in speech-like music, and/or where the bass-line is not melodic. [Monteverdi 1609] Bass wind-instruments are extremely rare in this genre [Agazzari 1607]

The most common accompaniment is theorbo and organ [Monteverdi 1609 for opera], theorbo alone [Caccini 1601, for chamber songs], harp alone [Agazzari 1607 for small ensembles], organ alone [Viadana 1602 for church music, Monteverdi 1609 for special operatic moments].

Arpeggios start on the beat, not before. [Kapsberger 1604, Frescobaldi 1615, Piccinini 1623, etc etc]. See also Agazzari’s [1607] warning against ‘soup and confusion’:

https://andrewlawrenceking.com/2013/10/08/sparrow-flavoured-soup-or-what-is-continuo/

Larger continuo ensembles are associated with concerted ensemble music. [Agazzari 1607, Monteverdi 1609, Landi 1631].

There is evidence for string consort accompaniment as an unusual special effect, written in by the composer [Monteverdi Combattimento 1624/1638, also Arianna 1608 according to eye-witness accounts, but the string-parts do not survive]. Whilst string-ritornelli often have to be supplied for arias (they are obviously required, but don’t always survive), there is no justification for adding string accompaniments to speeches generally.

As a rule of thumb, take treble A (‘tuning A’, 440, 465 Hz whatever) as the highest note for your realisations.

Gesture

Although the modern-day term is Baroque Gesture, period sources discuss full-body acting, including how and when to walk, facial expressions etc as well as hand gestures. [Cavalieri 1600, Monteverdi 1608, Gagliano 1608].

Gestures support the meaning, emotion and rhetoric of the text and are timed with the text. [Monteverdi 1624/1638, etc etc]

Gesture can look very beautiful, but should not be reduced to a ballet of the hands. They should support the text and help move the audience’s passions. A good rule of thumb is that if the audience become aware of your gesturing, you are doing it wrong!

Final notes notated long, but performed short, leave time for gesture between each phrase and the next. [Cavalieri 1600]

Similarly, the last note of a speech can be used to change position on the stage, for example in dialogues. This movement can begin on the penultimate note (i.e. the last Good syllable) already. [Gagliano 1608]

Read more about Gesture and Historical Action:

There is a modern-day trend to link the period practice of physical, rhetorical gestures with what today’s practitioners call ‘musical gesture’. In mainstream Music Psychology, Musical Gesture refers to body movements made by performers, but in Early Music it describes the concept that particular melodic fragments might be played in a way that goes beyond the literal notation to create powerful emotional effect.

Such transformations are clearly described by Caccini [1601], placed in the context of underlying Tactus and consistently in the direction of exaggerating contrasts in written note-values. Certain fragments found in toccatas and early sonatas are similar to the effetti, vocal ornaments for emotional effect, described by Cavalieri [1600], Caccini [1601] and others.

But I am sceptical about any significant historical link between these effetti and rhetorical (i.e. text-based) hand-gestures. At worst, the whole concept might be just an excuse for modern players’ bad rhythm!

Conclusion

This article has set out the technical information passed down to us from primary sources, how to perform speech-like dramatic monody by focussing on Text and Tactus.

The whole purpose of this style is not to tickle the ear, but to move the audience’s passions. Read more here:

The study of Historical Performance Practice is a fast-moving field. Much of what we thought was ‘authentic’ in the 1980s has been challenged by recent research. The conclusions I draw in this article will no doubt be revised in years to come, but I hope the citations will remain relevant and useful to readers and performers.

Let’s sing in such sweet turns of phrase, that our ensembles may be worthy of Orpheus! [Striggio, 1607]