Welcome back after the winter break! As storms batter the western isles, what better time to sit indoors and practise Irish Harp ornaments? And what ornament could be more Gaelic-sounding than a Triple Shake, Tribhuilleach or creathadh coimh-mhear? And how could I possibly resist making it ornament #3?

But at this point, I have to issue a warning. In the ornaments we’ve looked at so far, we’ve seen connections to (and differences from) European practice of the same period, and we’ve compared Bunting’s Table of Ornaments with the opportunities to use those ornaments in the pieces he prints later on. But there is no equivalent of this Triple Shake in European music, and (as we will see) our principal source, Bunting (1840) available here is unsatisfactory.

So this wonderfully Gaelic ornament remains somewhat enigmatic, and the realisation I propose here is necessarily conjectural. I look forward to your comments and alternative suggestions.

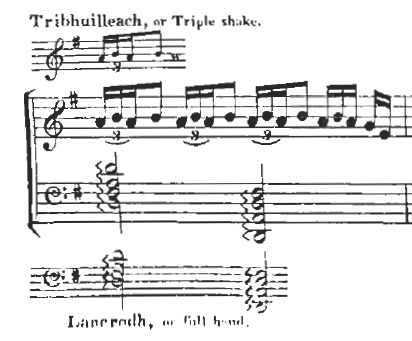

Here is the information from Bunting’s Table of Ornaments (page 25).

Remember that the period fingering notation uses + for the thumb, 1 for index finger, etc. (see Ornament #1 – The Long Shake). Although for several of the more complex ornaments Bunting gives information about stopping the sound, for this Triple Shake he does not. I believe this omission points us towards the solution I suggest at the end of this posting.

Bunting indicates opportunities for other Shakes frequently in the pieces he publishes, with the conventional Tr marking (from Italian trillo). Many of these opportunities are at Cadences (see Ornament #2 – The Cadential Shake). But there is only one appearance of the Triple Shake, on page 92 in the music section, in a piece Bunting describes as Cooee en Devenish or The Lamentation of Youths, composed by Harry Scott in 1603 for Hussey, Baron of Galtrim. According to the Bunting’s Preface p91, he noted down Cumha an Devenish from the playing of Dominic O’Donnell, a harper from Foxford in County Mayo. Bunting wrote the music into his notebook BMS12 in 1811, and the transcription published in 1840 abounds with those peculiar graces of performance alluded to in the Table of Ornaments.

This Lamentation is similar to another circa-1600 piece, Cumha Caoine an Albanaigh or Scott’s Lamentation for Purcell, Baron of Loughmoe (the late 17th-century English composer, Henry Purcell was a distant relative) who died about 1599 (page 6 in Bunting’s music section). These Lamentations are highly significant in Bunting’s output for they are linked to traditional rituals of mourning (in particular, the imitation of keening, the crying or wailing for the dead) and seem to preserve many details of ornamentation from two centuries earlier.

In his transcriptions of the Lamentations, Bunting takes special care to notate many ornaments, labelling them with cross-references to his Table of Ornaments. But it is far from certain that the harpers shared his view that these pieces were special. Bunting writes that O’Donnell appeared totally unconscious of the art with which he was playing. My working hypothesis is that Bunting’s 1840 version of the Lamentation of Youths was deliberately created as an exemplar of how to apply ornaments.

Some of those ornaments might well have been played by O’Donell in 1811 (and noted in BMS 12), others might have been played, not noted at the time, but remembered and restored in later versions. But I suspect that Bunting might also have added some ornaments (not played by O’Donell), according to his best knowledge of how ornaments were used, in order to complete his exemplar. A full analysis is beyond the scope of this article, but would be a fascinating topic for discussion at Scoil na gCláirseach 13th-19th August 2014 (details here) We can also look forward to a forthcoming article from Ann Heyman on the two Lamentations.

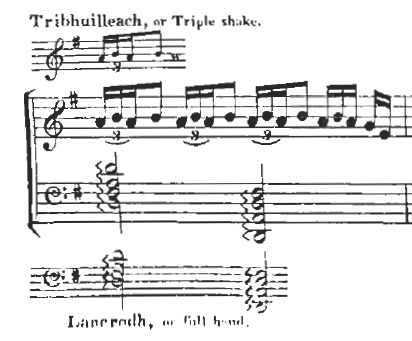

Meanwhile, there is plenty to think about in relation to the Triple Shake. Here it is, as Bunting applies it to the Lamentation of Youths.

Bunting applies the Triple Shake in the position of a Cadential Shake. The underlying simple melody is falling from A to G, and the accompanying harmonies move conventionally from D major to G major. The rhythm of the Triple Shake corresponds to the Table of Ornaments, although the notes are three strings higher, A and B instead of F# and G. The fourth beat of the bar is filled in with an ornamental Turn, with a very Irish-sounding gap (the turn moves from G to E, omitting F#). So far, so good.

But now the problems start. If you play the Triple Shake with the fingering given in the Table of Ornaments, since there is no damping, both notes ring on. If anything, the B rings louder and longer, since it is written as a longer note, and the A will damped as you replace your finger ready to start the next element of the Triple Shake, or ready to start the final Turn. The resulting sound is messy and discordant, since the B does not fit well with the D major harmonies.

Simon Chadwick speculates that the Triple Shake is therefore an ornament on the note B, that begins on the lower auxiliary note of A. But this still leaves the problem that the B does not fit with the accompanying harmonies (proudly labelled as another piece of authentic detail Lancrodh or full hand.) And when we looked at the Cadential Shake, we saw that the Cadence with accented A falling to G is very typical.

And when we compare this one bar from the Lamentation of Youths to the remainder of Bunting’s output, an even more serious problem emerges. Not only is this the only example Bunting gives of a Triple Shake, but

There is no other opportunity to apply the Triple Shake like this, in the whole of Bunting’s output.

There are many opportunities for Cadential Shakes, but they are all much too short for the three-beat Triple Shake.

Meanwhile, there is something rather unsatisfactory about Bunting’s application of the three-beat Triple Shake to the four-beat A of his unique example in Lamentation of Youths. He has to fill up the missing beat with a Turn, but he told us in the Table of Ornaments that the old Irish harpers did not finish the shake with a turn, as in the mode adopted at present.

My hypothesis is that in the enthusiasm to include lots of ornaments in a piece that seems to exemplify the circa-1600 style, the Triple Shake was applied in the wrong place. There is no place like this in the rest of the repertoire, and the Triple Shake doesn’t really fit, even here. Bunting’s limited understanding of the function of this particular Shake is also shown by the lack of information on damping.

But there is an opportunity for a Triple Shake that occurs many, many times in this repertoire. Many tunes repeat the final note, the tonic, three times.

Bunting’s first music examples are at page 15 of the Preface. The first phrase of the first piece ends with three Cs. The second phrase ends with three Bbs. The third phrase ends with three Gs, and is repeated. The next phrase ends with three Cs, and the final phrase repeats the second phrase, ending with three Bbs.

The final phrases of both parts of the next tune end with three Gs. There are hundreds more examples, throughout the book. Indeed, this Triple Tonic is an instantly recognisable feature of Irish melodies.

So I suggest that we can apply the Triple Shake not to the penultimate note on the Dominant harmony (as for the Cadential Shake), but rather to the final note, the Triple Tonic.

All we need to do now, is to sort out the lack of damping in Bunting’s Table of Ornaments. Here is my solution, with modern notation (1 = thumb, 2 = index finger etc). I’ve chosen to put the Triple Shake on G, since we often play melodies in G major, because they suit the standard tuning of the historical Irish harp.

The finger-movements are like a small section of the Long Shake. After playing G A G quickly, the index finger drops silently onto the A, damping it so that the main note G rings on. That’s one element – play three elements to make a Triple Shake.

So now when you see a Triple Tonic, you can give it a twist with a Triple Shake …. Cheers!

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our website www.TheHarpConsort.com .

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago, and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions.