How far do you and your ensemble go, when ornamenting music by Monteverdi and his contemporaries?

1) Go on, do some ornaments like on the CDs.

2) Not too much ornamention, [insert name here]!

3) Not THAT ornament!

4) Let’s study examples of ornamentation from period ornamentation manuals.

5) Let’s study how to apply those ornaments, by looking at scores and treatises.

I thought I was somewhere between steps 4 and 5, but in researching for this article, I began to realise that the typical approach of today’s Early Music is not just slightly off-target, it’s diametrically opposed to historical evidence. Even for such well-known works as Orfeo (1607) and the (1610) Vespers, our understanding of ornamentation needs a complete reset.

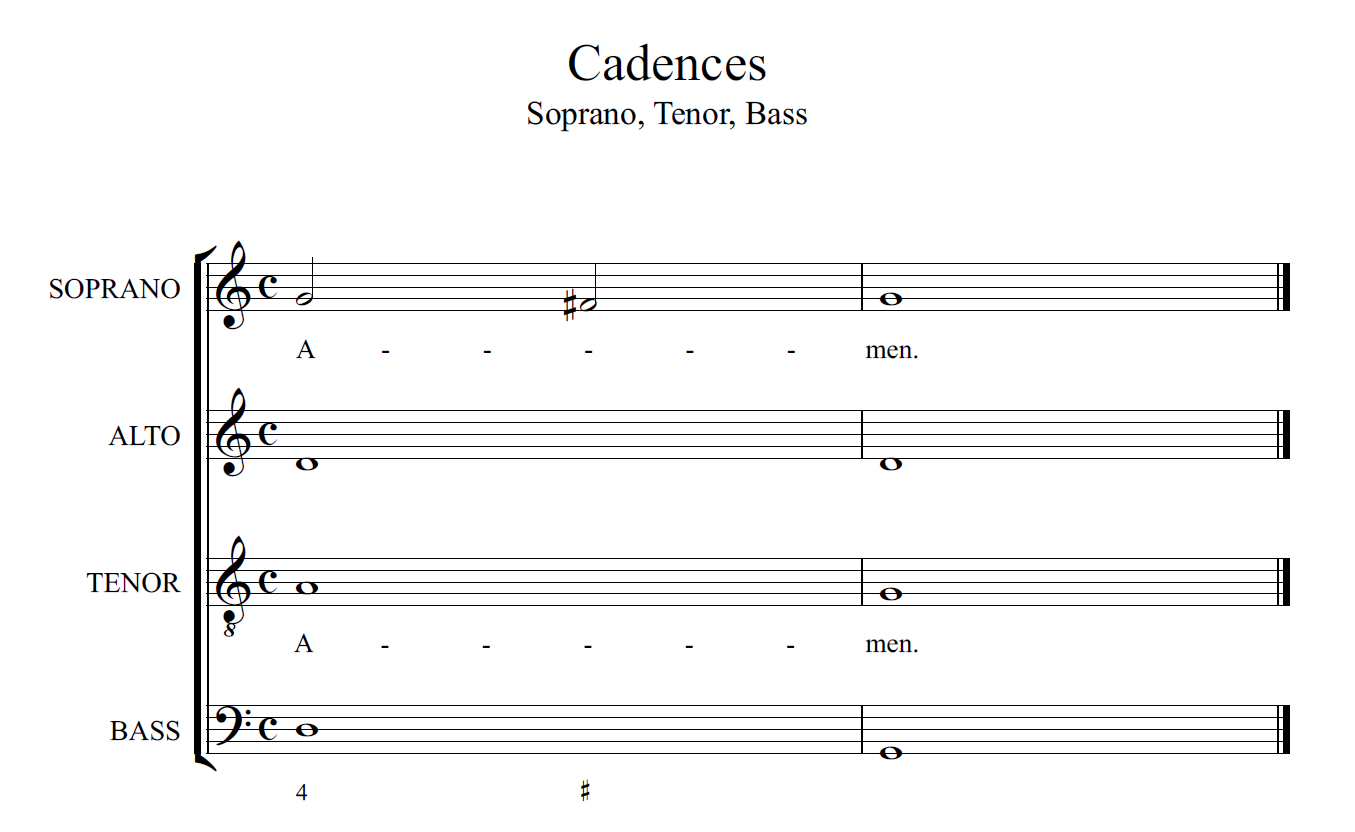

How should we ornament Cadences?

Often, the problem is expressed as a well-intended question:

What to do with all those cadences?

The Bass Cadence usually appears in the lowest voice. Tenor and Soprano cadences can be in any voice. The names Tenor and Soprano are used to identify the melodic shape, not the particular voice.

In particular, in dramatic, sacred or courtly monody (let’s not muddy the waters by calling it Recitative more here), how should we ornament what seem to be over-frequent cadences in long notes (minims or semibreves), especially the descending whole tone of the Tenor Cadence?

Diminution Manuals

When we look to the sources, there is an easy answer to this question. There are several historical treatises on the Art of Diminution, showing how any long note can be divided into shorter notes (hence the period English term for this practice, Division), with many examples of passaggi to be taken as models for prepared or spontaneous ornamentating. To ensure that the Diminution flows smoothly to the next note, these examples are categorised by the interval between the two long notes: up or down; unison, second, third, fourth etc. So all we have to do is select a treatise from the early 1600s (or a little earlier, representing the style that Monteverdi’s singers would have learnt from their teachers), and turn to the section on descending a second, and we can see a dozen or more historical solutions.

If a modern-day singer prefers to learn by ear (a reasonable and historical preference), then instead of studying recent CDs, it’s easy to record a selection of historical examples, or to transcribe period dimutions into Sibelius and export a sound-file. There are links at the end of this article for Divisions of the Descending Second by Virgiliano (1600) and Ortiz (1553). And this is a good moment to mention Helen Roberts’ excellent Passaggi app for improvisation and ornamentation, which offers a 21st-century learning approach using period sources. Practice your divisions here www.passaggi.co.uk

Making divisions on a descending second is an attractive and source-based answer for ornamenting Monteverdi’s monody. Unfortunately, it’s the wrong answer! And that’s because we have been asking the wrong question. Instead of asking “how should we ornament cadences?”, we should ask “how should we apply ornamentation?”.

How should we apply ornamentation?

The difference between these two questions becomes clear if we look at Caccini’s Le Nuove Musiche (1601). [Translation of the Preface and link to the original print here.] For his ‘noble manner of singing’ Caccini seeks to update the 16th-century practice of diminutions by ‘avoiding the old-fashioned manner of passaggi‘, which is ‘more suitable for wind and string instruments than for the voice’. Nevertheless, his didactic examples and composed songs have plenty of diminutions, fitting into the continuing tradition of Arie Passaggiati [ornamented arias]. So in preparing this article, I thought I would be able to extract from Le Nuove Musiche a useful selection of models for ornamenting cadences, to compare and contrast with Ortiz and Virgiliano.

I was wrong. Firstly, there are few Tenor Cadences in Caccini’s songs: he uses many Imperfect Cadences (7 6, in continuo-speak), and at Perfect Cadences (4 3) he prefers to give the voice the Soprano Cadence. But even more significantly, when he does write a Tenor Cadence, he almost always leaves it plain. There might be plenty of diminutions earlier in the phrase, but at the cadence itself there is a plain long note (in a couple of instances, he adds a simple trillo).

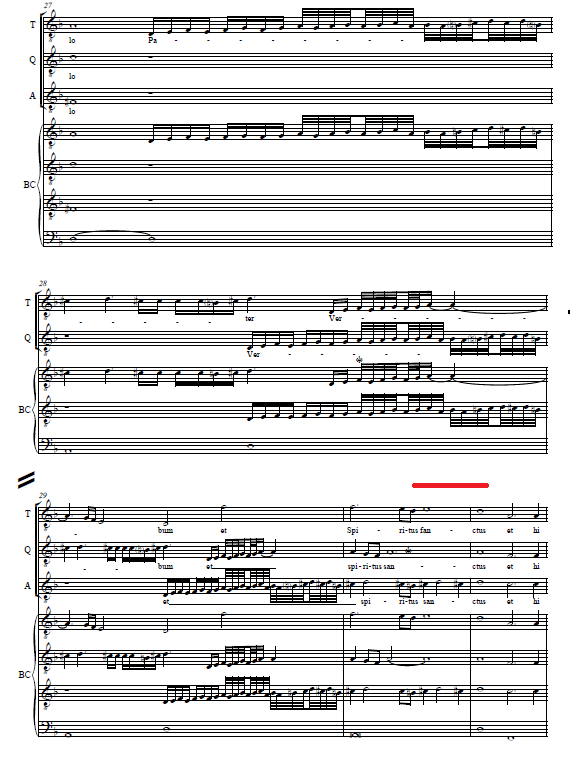

Somewhat rattled by this, I turned back to Monteverdi’s most famous examples of written-out diminutions: Orfeo’s magnificent ornamented aria Possente Spirto , the famous Echo piece from the Vespers, Audi Caelum and Monteverdi’s take on the Three Tenors: Duo Seraphim. Here as in Caccini’s teaching examples and chamber-songs, it is clearly seen that the passaggi finish just before each cadence.

Standard modern practice – leaving a phrase plain and then dividing the long note at the cadence – is the opposite of what Caccini and Monteverdi notate.

Prefaces & Treatises

In addition to Diminution Manuals and composed Arie Passeggiati, there are written commentaries on ornamentation practices in several early seicento Prefaces and Treatises.

In the Preface to the earliest surviving baroque music-drama, Rappresentatione di Anima e di Corpo (1600), Cavalieri’s instruction for singers is ‘senza passaggi‘ (and for the continuo, ‘senza diminutioni‘. In sacred music for solo voices and continuo, Cento Concerti Ecclesiastici (1602), Viadana warns singers not to add to the few melismas he writes. Caccini (1601) similarly remarks that he has notated all that is necessary for his chamber-songs.

Peri’s Preface to Euridice (1600) links, translation and commentary here emphasises the speech-like quality of his dramatic monody, in which intermediate syllables are sung so lightly that their pitch is almost indiscernible. He mentions that the famous soprano Vittoria Archilei has added diminutions to some of his previous compositions (‘more to obey the practice of our times, rather than because she thinks that therein lies the beauty and force of our singing’), and hints at ‘those beauties and delicacies which cannot be written, or if written cannot be learnt from notation’. Caccini also warns that the most exquisite touches – squisitezze – are beyond notation, but that they can be learnt from written examples combined with practice.

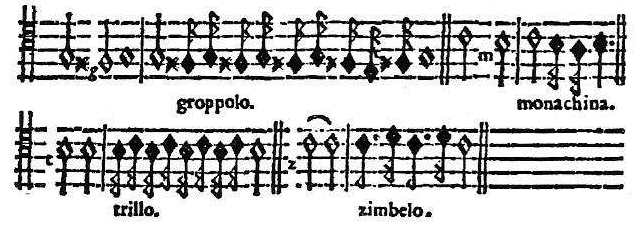

Effetti

Caccini describes and shows how to apply a new type of ’emotional ornaments’, vocal effetti (effects) that produce affetti (emotions), instead of old-fashioned passaggi. Most frequently mentioned are crescendi/diminuendi on a single note, especially such on exclamatory words as Ahi!, Deh! etc. Phrases can be started with an exclamatione (forte-subito piano -crescendo, all on one note), with piano-crescendo on the first note, or rising from a third below. In the middle of the phrase, rhythms are systematically altered to make long notes longer, short notes shorter. For cadences, Caccini gives two simple ornaments: the one-note trillo (for the Tenor Cadence) and the two-note gruppo (for the Soprano Cadence).

Both examples (contrary to some modern-day recordings and performances) accelerate from slow to fast.

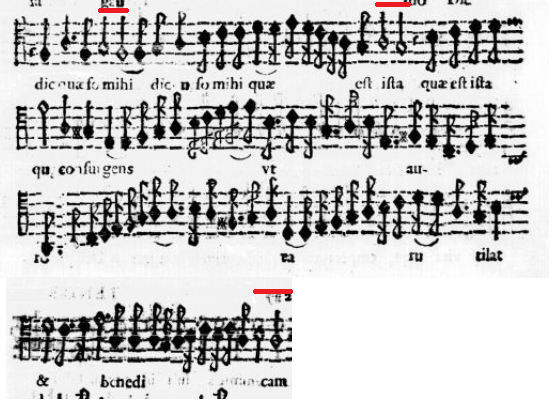

Similar effetti were introduced by Cavalieri (1600) in his Preface, and are indicated in the score itself by the intial letter of each effect. G = groppolo, T = Trillo etc.

Listen to and learn by ear Cavalieri’s & Caccini’s effetti here.

Cavalieri applies these effetti infrequently, perhaps just three or four times for the largest role (Anima), and less often for each supporting role. There are just two indications of gruppo in ensemble music.

This way of ornamenting may not be as ‘new’ as Caccini suggests. Giustiani (1628) describes differing ornamentation practices for sacred polyphony (passaggi) and monody (effetti) amongst performers in Rome as early as 1570. See Timothy McGee’s “How one Learned to Ornament in Late-Sixteenth Century Italy”.

Rhythmic Alteration

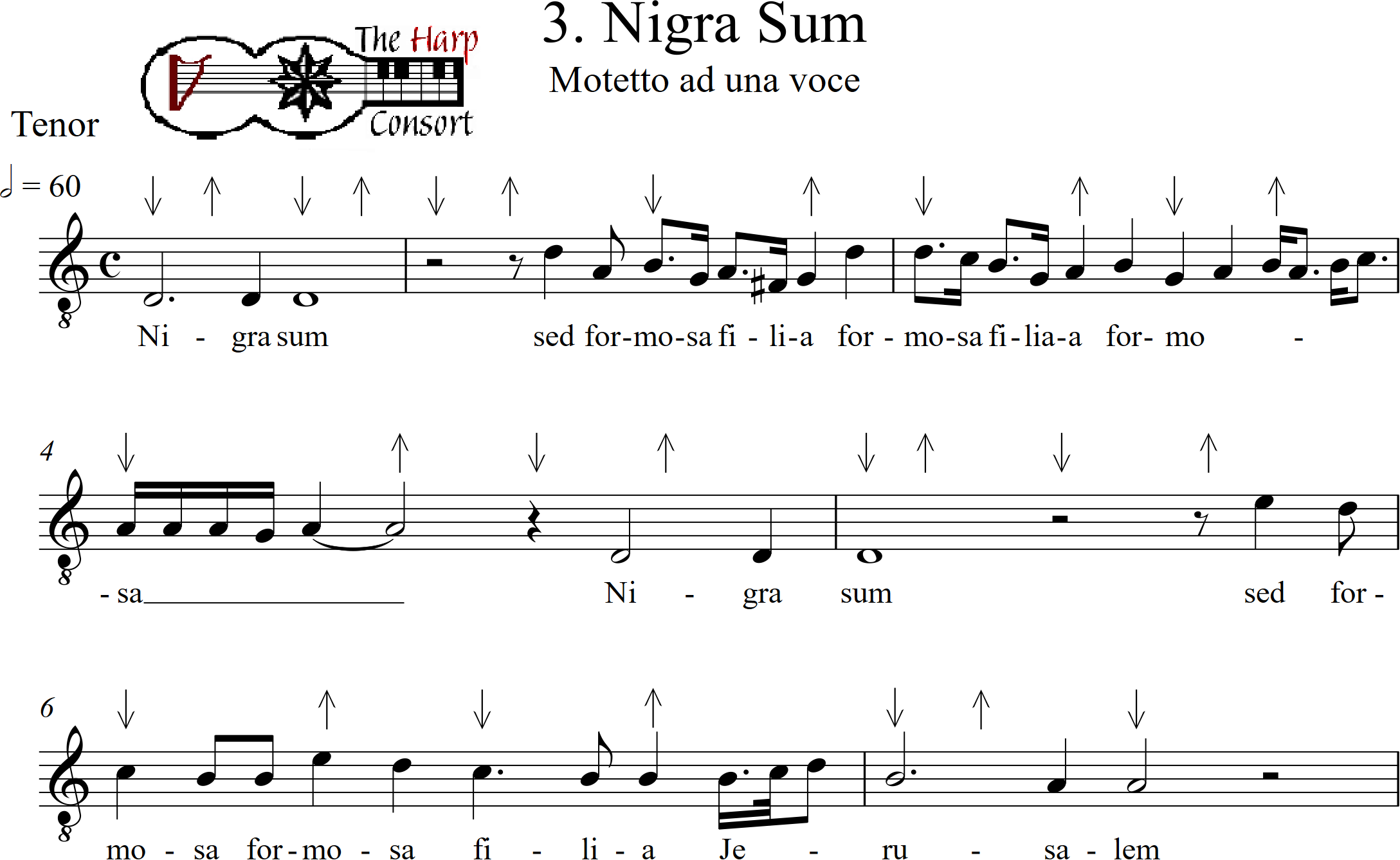

Monteverdi notates rhythmic alterations in which the voice anticipates or lags behind the continuo accompaniment.

In bar 2, the singer’s “sed” is immediately after the Tactus-beat (just a quaver rest), ahead of the continuo-bass (which comes a crotchet after the beat)

In bar 4, the singer’s “Ni…” again enters unexpectedly early, anticipating the continuo-bass which is played on the next Tactus-beat

In bar 5, the singer’s “sed” is immediately after the Tactus-beat, and the continuo-bass has a minim, played on the Tactus-beat. Although the singer’s syncopated rhythm is similar to bar 2, the effect here is of a delay, rather than an anticipation, because the structure-defining continuo-bass plays first.

At the beginning of bar 4, notice also the effetto ornament on the final note of the Imperfect Cadence: Monteverdi uses this effetto also in Orfeo, but only a couple of times in the whole opera.

My esteemed colleague, Xavier Diaz-Latorre, makes the excellent suggestion that one can better understand these jazzy syncopations by first trying the “square” version, with voice and continuo together in the obvious way, in order to appreciate the subtle effect of the altered rhythm. Perhaps singers might introduce this effect spontaneously, even where it is not notated, whilst continuo-players maintain the steady groove of Tactus. Monteverdi, Caccini and Jazz here.

Caccini gives many examples of rhythmic alteration. The common feature is that long notes are extended to become extra long, and short notes are correspondingly adjusted to be even shorter, within the same Tactus-duration.

Speech-like or Song-like?

In the Preface to Comboattimento (published in 1638, but first performed in 1624), Monteverdi writes that Testo, the Narrator, should avoid gorghe and trilli, except in the one Aria.

This is supported by the anonymous Il Corago (c1630), who notes [at the end of Chapter X] that ‘there are only a few cadences appropriate to each voice, and these occur frequently’. Nevertheless, dramatic monody ‘lacks those ornaments and beauties which greatly embellish singing: I mean [a lack] of passaggi, trilli, gorghiggiamenti, because these are too far removed from the normal manner of speaking and work against moving the passions… and for this reason singers are forbidden to use these ornaments and adorments when they act [or perform, declaim] in this style.’

In Chapter XI section III, Il Corago explains that ornamentation can be applied to diegetic songs (representing on stage the act of singing). ‘To give the musician an opportunity to use all the artistry of music, such as gorge in passaggi and sweetly drawn-out melodies, the poet can have some of them represent singing… giving an opportunity to both composer and singer to make those passaggi and beauties which are absent from the current style recitativo‘.

For the whole genre of dramatic monody, Doni [Annotationi pages 60-62] makes a similar broad distinction between speech-like and song-like music, and categorises speech-like monody into three types: Narrative, Expressive and Special. For Doni, (as for McGee and me), the word recitativo is problematic, but what he calls Special Recitative is closer to song (although he does not approve of that!) It is found in many pastoral scenes (Doni’s examples are from the opening scenes of Peri’s Euridice) as well as in Prologues. It is tempting to assume that Special Recitative might therefore allow some passaggi, but the evidence of seicento music-drama scores suggests that although there is plenty of music that Doni would categorise as Special Recitative, hardly any passaggi are notated.

Nevertheless, the Prologue to the 1589 Florentine Intermedi has wonderful passaggi, sung by Vittoria Archilei. These passaggi stop before each cadence.

There is also an Aria Passeggiata by Caccini, in which passaggi in the middle of the phrase lead seamlessly into gruppi at cadences. The character-role is a Sorceress who will tear down the moon from the skies.

Most probably, the Intermedi reflect earlier practice, as yet less influenced by the northward spread of Neapolitan and Roman influences.

In 1607, Orfeo’s famous aria Possente Spirto shows the seicento application of the old-fashioned aria passeggiata genre , as the protagonist sings a diegetic song at the central moment of the drama. The divisions are spectacular and charm Caronte’s ears, even though they do not move his emotions. The passaggi end before each cadence, though Monteverdi adds effetti at some cadences.

Echoes

Echo scenes were a special case, where the poet cleverly answers his character’s questions with a responding Echo, whilst the composer provides short bursts of passaggi for the Echo to imitate in reply. There is nearly always a moment where the audience are led to expect an answer, but the Echo remains silent. Cavalieri’s Anima sets a musical challenge for the imitating Echo with ornamentation that aptly supports the meaning of each key word, and the poet triumphs at the end of the scene by creating a complete sentence from the Echo’s replies.

In Orfeo, Striggio’s Echo is less witty, but more expressive, and Monteverdi does not notate passaggi for the scene, perhaps because the key words are so emotionally loaded.

Audi Coelum brings the theatrical device of the Echo into the sacred domain, and enlivens the syllabic style of theatrical music with thrilling passaggi.

Genre distinctions – Phrases & Cadences – Passaggi & Effetti

Putting all this information together, we can begin to understand in which genres, and at which moments within the phrase, different types of ornamentation might be applied. We have to distinguish between song-like music and speech-like dramatic monody; between final cadences and the preceding phrase; between dividing long notes into elaborate passaggi and adding restrained effetti.

Passaggi are associated with the main body of the phrase, with song-like music, and with ear-charming delight. Effetti are associated with cadences, with speech-like music, and with ‘moving the passions’. All kinds of musicial complexity, including passaggi, were considered inappropriate in dramatic monody, because they diminished the speech-like quality of the musical declamation, and therefore worked against emotional communication. But if an actor represents a character singing, then ornamentation becomes ‘realistic’ and appropriate.

Perhaps there was a slight tendency for song-like writing (Doni’s Special Recitative) to encourage small doses of passaggi even in theatrical music, but there is scant evidence for this. The reverse is evident: certainly there was a strong tendency for theatrical restraint (from ear-tickling divisions) and passion (in emotional effects) to be applied to chamber and sacred monody, especially where the text suggested a first-person embodiment of a character-role. In this sense, the soloist of Audi Coelum represents the character-role of a soul crying out to heaven for counsel; the tenor who sings Nigra sum sed formosa speaks the words of the Shulamite “I am a black girl, but beautiful”!

Where passaggi were employed, they end before the cadence itself. Cadences can have trilli, gruppi etc, but only infrequently.

How to deal with cadences?

This leaves us wondering, what we should do with the cadences, if we don’t ornament them. Doni describes [Annotatione page 362] the standard practice of early seicento theatrical monody (even though as a theorist, he disapproves of it). He is shocked at the contrast between the fully sung penultimate syllable and the almost unpronounced final syllable.

The penultimate note (the accented syllable of the word, and the Principal Accent of the poetic verse) is nearly always a long note (minim or semibreve) and is really sung (in contrast to the speech-like delivery of the rest of the line, clearly described by Caccini and Peri as ‘something less than singing’). The final note (the unaccented final syllable) is short and unaccented, barely pronounced. Il Corago warns that final syllables should not be dropped entirely, but Cavalieri indicates a silence at the end of almost every phrase. Gagliano’s stage directions have the singer starting to move on the penultimate syllable of a strophe, so that they have already turned away from the audience for the final syllable.

In sharp contrast to today’s standard practice, the period recipe is: almost speak in dramatic styles, or add passaggi to song-like phrases, but don’t ornament the cadence. At the cadence, really sing the penultimate note nice and long, and then the last note is short and unaccented.

Meanwhile, if you actually count the cadences, they are usually no more frequent in monody than in polyphony. Of course, prima prattica polyphony disguises cadences by avoiding simultaneous cadences in all the voices, whereas in monody voice and bass usually make the cadence together. But the percieved ‘problem’ of cadences may be one that modern performers have inflicted on themselves, by inappropriately sustaining last notes and by attempting to ornament in the one place they should not!

Ornaments or emotions?

Doni (from his viewpoint as a theorist) and the utterly practical Il Corago both distinguish between song-like music with passaggi that delights the ear, and speech-like music that focusses on the pronunciation and emotions of the text in order to move the listener’s passions. In Orfeo, La Musica can do both:

Io su cetera d’or cantando soglio

Mortal orrechio lusinghar talhora

E in questo guisa a l’armonia sonora

De la lira del ciel, piu l’alme involglio

Singing to the golden lyre as always,

I can beguile mortal ears for a while.

And in this way, with the sonorous harmony

of the lyre of heaven, I can even influence souls.

But significantly, Caronte is not moved by the passaggi of Possente Spirto. And Il Corago explains why [Chapter X]: ornamentation ‘distracts from the material that is sung about, and transfers your attention to the simple aural delight in masterly singing’. Doni describes this same dichotomy in terms of the rhetorical purposes of music: to delight, or to move the emotions? Caccini similarly contrasts the old-fashioned delight in passaggi with a new focus on moving the passions by means of crescendo/diminuendo, esclamationi and other effetti.

In this context, our modern focus on ornamentation of Monteverdi’s Recitative misses the point entirely. Instead of trying to apply passaggi to the cadences of dramatic monody, we should be focussed on delivering text to and inducing emotional response amongst audience members. And that’s why I’ve utterly lost patience with that ornament: it’s the wrong answer to the wrong question in the wrong situation.

Finally, as promised, here are links to Diminutions of the Descending Second by Ortiz (1553) transcription and soundfile and Vigiliano (1600) transcription and soundfile. But these files come with a HIP health-warning: the entire argument of this article is that it is not historical to apply these passaggi to the cadences of Monteverdi’s dramatic monody.

Pingback: Altri canti senza battuta: Madrigals of Love, War & Tactus | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Passaggi: Della Casa & Bovicelli on the True Way to make Divisions | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Cantar con gratia – a forgotten ornament? | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Introduction to mid-18th-century Ornamentation | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Recitative for Idiots (but don’t use that word): three types of Dramatic Monody | Andrew Lawrence-King