Rhythm is the beating heart of music, from the powerful throb of heavy rock to the sensual swing of jazz and the ‘vacillating rhythm’ of romantic rubato. For many musicians and listeners today, the very word ‘expressive’ suggests rhythmic fluidity. Around the year 1600, John Dowland, William Shakespeare, and Giulio Caccini agree that rhythm is a high priority:

Music is nothing else than Text, and Rhythm, and Sound last of all. And not the other way around!

Caccini Le nuove musiche 1601/2

But what did 17th-century musicians mean by Rhythm? A rock drummer’s groove? A jazz singer’s swing? 20th-century rubato? Just as instruments, pitch and temperament, bowing styles and ornamentation all vary between different periods and repertoires, so the aesthetics of rhythm also show historical change.

This is a huge subject. Detailed investigation of attitudes to rhythm around 1600 are a major strand of our six-year Performance research program at the Australian Centre for the History of Emotions. Dance and Swordsmanship sources set the context for musical tempo. Frescobaldi, Caccini and Peri give us insights into Italian subtleties of rhythm. The very concept of Time itself must be studied, in order to understand how musicians were thinking in that pre-Newtonian age.

(Isaac Newton Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica 1687 sets out the concept of Absolute Time)

Nevertheless, the essential practicalities of period Rhythm are already well understood, although only partially applied in today’s Early Music performances. George Houle’s 1987 Meter in Music, 1600-1800 provides a summary of historical sources, setting the context for this period of fundamental change. 17th-century theorists and performers tried to reconcile incompatible elements: the old system of triple-time proportions and the newly fashionable French dances; the gradual shift from proportional signs to modern time-signatures; the persistent concept of a (more-or-less) fixed tempo ordinario and the proliferation of speed-modifying words, allegro, andante etc; the distinction between measured meter and modern accentual rhythm.

But what simple, practical guide-lines can we draw from all this?

As elementary music students, many of us were taught to manage difficult rhythms by counting the smallest note-values, adding these up to measure longer notes. Before 1800, the contrary held: musicians counted a long note-value, and divided this up to measure shorter notes. Purely mathematically, there should be no difference between the two approaches, but (since musicians are human), the practical results are measurably different. Even more importantly, the slow count feels different.

Around 1600, this slow count is called Tactus. Its slow constancy is an imitation of the perfect motion of the stars, whose circular orbits create the heavenly sounds of the Music of the Spheres. It is felt in the human body as the heart-beat and pulse, or measured as a walking step. In practical music-making, it can be shown by an up-and-down movement of the hand, or by a swinging pendulum.

(Of course, 17th-century musicians did not have digital watches or metronomes, but Galileo had noted the pendulum effect around 1588, observing a swinging chandelier in Pisa cathedral – see illustration above. In another posting, I’ll report on some recent experiments with pendulum tactus.)

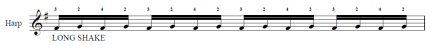

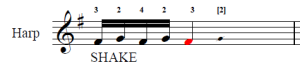

Around 1600, typically the Tactus will be on minims (half-notes), somewhere around MM60. Down for one second, Up for the next second. You create crotchets (quarter notes) by dividing each Down and each Up in two. “Down-and-Up-and.”

The simple, steady movement of the hand, Down-Up, makes it easy to manage changes of Proportion. Keep the hand movement the same, but now divide it into three beats on the Down, and another three on the Up: this gives Tripla. Making the Down long, and the Up short (whilst keeping the duration of the whole Down-Up cycle the same) gives Sesquialtera: two beats on Down, one on Up.

Grouping notes into phrases, and choosing where to place the accents is independent of Tactus. Tactus simply measures time. This is the crucial difference between early and modern attitudes to rhythm: Tactus and Accent are independent, whereas our modern Downbeat implies accentuation.

The independence of Tactus and Accent allowed 17th-century musicians to notate triple rhythm under what looks to us like a “common time time-signature” of C. Time is being measured by dividing the minim tactus into two crotchets, but the music is phrased in groups of three crotchets. Professional dancers do something similar today, counting everything in blocks of 8, so that a waltz is counted:

123/456/781/234/567/812/345/678

Before 1800, counting (i.e. measuring time) and accent are independent. They can coincide, but they don’t have to.

Tactus and Proportion were central concepts in period music-making.

Tactus directs a Song according to Measure.

John Dowland Micrologus (1609) translated from Ornithoparcus (1517).

Ha, ha, keep time! How sour sweet music is / When Time is broke, and no Proportion kept!

William Shakespeare Richard II Act V Scene v (c 1595)

In today’s Early Music, the acceptance of Tactus principles varies. Stronger principles are supported by academics more than they are applied by performers.

- Slow count

This is widely accepted, and many performers work with and teach a slow count.

- Proportions

Amongst academics, there is debate about precisely how to interpret Proportional changes, but the central concept of an underlying constant slow count is not contested. Amongst performers, adherence to Proportions is regarded as ‘hard-core’ HIP, and ‘too academic’ for some.

- Consistent Tactus: a whole “Song according to Measure”

Though the period evidence supports this, very few performers are prepared to relinquish their romantic rubato.

- “Tactus directs a Song”

In most modern performances, a conductor directs.

- Soloists follow the accompaniment

Explicitly stated by Leopold Mozart (1756), clearly implied by Jacopo Peri (1600), and the basis of the entire period practice of Divisions, this is almost universally ignored today.

- Rhythm in Recitative

Most singers today are astonished at the mere suggestion that Monteverdi might actually have meant something by all those complex rhythms that he forced his printers to set in type.

- Tactus in Recitative

Very few performers have tried this. However, conductors in recitative are commonplace…

- Consistent Tactus for a large-scale work

I was first introduced to this concept by Holger Eichhorn, director of the Berlin ensemble, Musicalische Compagney. Paradoxically, consistent Tactus often results in more contrast in what the listeners hear, since (without the discipline of Tactus) musicians tend to pick a slower tempo when the notes go fast, ironing out the composed contrasts. It is very rarely tried today.

- Consistent Tactus for an entire repertoire, say all Caccini songs, or everything by Monteverdi.

There is considerable evidence for this, and some academics argue for it. I know of only one other musician today who supports it in practice: continuo-guru Jesper Christensen.

At CHE, we are investigating Baroque Time, researching period Philosophy and the aesthetics of Rhythm, testing all our findings and hypotheses in experimental productions. Our six-year mission is to boldly go where 17th-century musicians have gone before, but few performers today have followed: we are applying all these Tactus principles in teaching, rehearsals and performance. So far, the results are academically and artistically convincing, with performers and (most importantly) audiences responding very positively.

You can see a video report of our Tactus-based production of Monteverdi’s Orfeo here.

But I’ll give the last word to John Dowland:

Above all things keep the equality of measure. For to sing without law and measure is an offence to God himself…

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our website www.TheHarpConsort.com . Further details of original sources are on the website, click on “New Priorities in Historically Informed Performance”

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago, and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions.