This posts continues my study of a very particular repertoire featuring female composers, works by Milanese nuns in the mid/late 17th century. This investigation is associated with the performance projects of Kajsa Dahlbeck’s Earthly Angels ensemble (read more here), which are underpinned by Kajsa’s own research.

My previous article The Soul of Music in Women’s Hands discusses compositions by Isabella Leonarda (1620-1704). Now I turn my attention to Rosa Giancinta Badalla (c1660-c1710).

Badalla’s book of solo motets with continuo accompaniment, Motetti a voce sola (1684) – 10 for soprano, 2 for alto – contains pieces for Christmas, Easter, for any Saint’s day, and for the patron saint of her convent, Santa Radegunda. This fascinating collection has many interesting features for researchers and performers alike, and I’m looking forward to Kajsa’s forthcoming performances. In the meantime, this post takes Badalla’s publication as a case-study in the period notation of Tempo.

Context

The priorities of the early seicento were encapsulated by Caccini in Le Nuove Musiche (1601): “music is Text and Rhythm, with Sound last of all.” More on Caccini here. Considering rhythm, the role of the performer – all the way from the mid-16th century to the late 18th – is to find the ‘correct’ tempo, not to invent their own arbitrary speed.

During the long 17th-century, composers indicate rhythm and tempo with precise notations, and those notations change during the course of the century. Certain rhythmic freedoms are clearly described in the early seicento, notably by Caccini and Frescobaldi. Frescobaldi Rules OK here.

The performance context for rhythm – again, all the way from the mid-16th century to the late 18th – is defined by Tactus and Proportions. Tactus from 16th-18th centuries here.

The steady, slow duple beat of Tactus (around 1 beat per second) is like the pendulum of the clock, which drives the various cogs at different, but interlocked, speeds. Those cogs are the various Proportions of ternary measure.

The mathematical precision of this system is an earthly imitation of the perfect movement of the heavens, driven by the hand of God. Nevertheless, humanist music-making allowed subtle adjustments to the (theoretically ever-constant) Tactus, creating time-changes between contrasting sections – i.e. contrasting movements.

Tempo

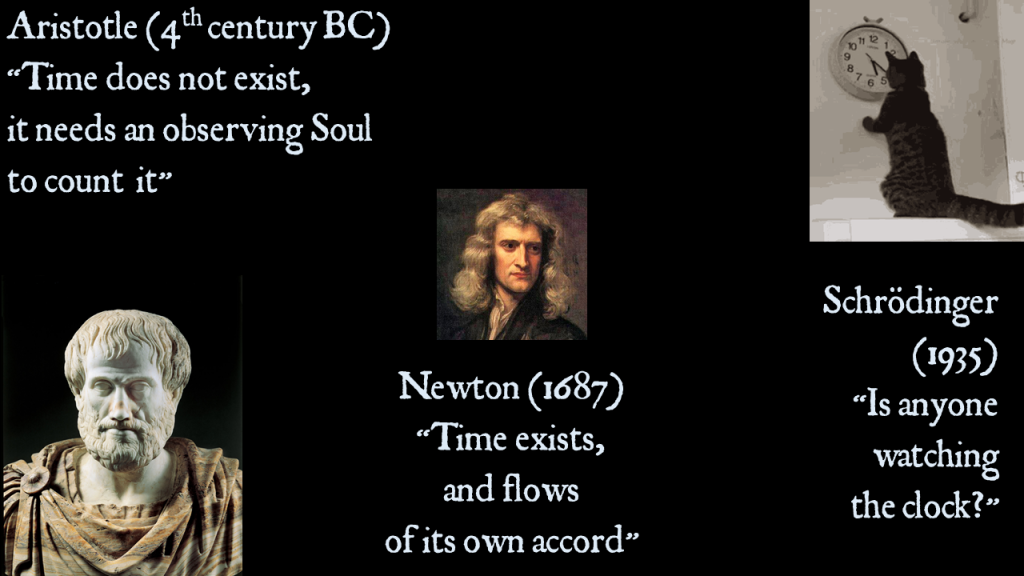

Nowadays, we use the word tempo to mean the ‘speed’ of the music, how fast does it go. But circa 1600, tempo meant Time itself, the measurement of real-world time in seconds. And this is not Newton’s (1687) Absolute Time, it is Aristotelean Time, which does not flow of its own accord, but is dependent on movement, and upon an observing Soul. More on Aristotelean Time here.

Aristotelean Time calibrates the musical notation of the mensural system to the real world, so that the note-values on the page “come to life” with sound and duration. More about Time, the Soul of Music here.

The essential movement, without which Time cannot be counted, is provided by a human hand, imitating the hand of God to administer a constant, equal and unchanging beat – battuta – also known as the light touch of Tactus. Zacconi explains that misura, the measuring of music time in mensural notation, battuta, and Tactus are all the same thing, Time itself.

A century later, this has changed. Whilst note-values are still seen as Quantitatively precise, the subjective Quality of how the music feels is understood to be variable, and it is this emotional Quality that is now called tempo (or in French, mouvement). More about Quality Time here.

This first conceptual shift in the meaning of the word tempo – from real-world Time to emotional Quality – is happening during the period under discussion in this article.

The second paradigm shift – from Aristotelean to Newtonian Time – happens much later. Sustained, fierce resistance to Newton’s ideas prevented them becoming effective in music-making until probably the early 1900s. Newtonian Time is a pre-requisite for the modern concept of tempo as the ‘speed’ of music, since we need Absolute Time as a benchmark to measure variable speeds.

Notation

The late 17th century is a less familiar transitional phase between two contrasting notational systems that have been more intensively studied by modern-day researchers: the mensural marks of Monteverdi’s (and in Milan, Cima’s) generation; and the time signatures of Bach and Handel. This transition was gradual: some features of the mensural system were already obselete for Monteverdi; but the 16th-century concept of a ‘standard’ or ‘correct’ time – tempo ordinario or tempo giusto – remained in force throughout the 18th century.

Nevertheless, one crucial change can be seen in the nuns’ publications: that change is underway in Leonarda’s notations, and is complete in Badalla’s publication.

This change affects the notation of ternary meter. At the slow extreme, movements in three semibreves fall out of use: at the fast extreme, such markings as 3/8, 6/8 and 12/8 appear. Thus far, I have not seen the old and new notations appear simultaneously in a single work; and only once within a single publication.

Proportions

Monteverdi notates Proportions with what are undeniably mensuration marks, though much of their meaning has evaporated by the early 1600s. I have argued elsewhere that Roger Bowers’ theory that these marks retain their full and complex medieval significance is incompatible with the need for performers (working from part-books, and often with minimal or no rehearsal) to come to rapid and unanimous decisions at each change of Proportion.

Scholars agree that bar-lengths are arbitrary in this period. Note that in the 17th century battuta means ‘beat’, and not ‘bar’ as in modern Italian.

The key feature of Monteverdi’s Proportional notation is the choice of note-values. Three semibreves show the slowest Proportion (Sesquialtera); three minims show a medium-fast Proportion (Tripla); six semi-minims shows the very fast (Sestupla) Proportion. Read more about Monteverdi’s Proportions here.

Whatever Proportion is in use (and different voices may be in different meters and/or different mensuration marks), the duration of any particular note-value, a minim say, is the same in all Proportions. Carissimi (Ars Cantandi, 1696) puts it very simply: “the triple-metres all agree with regard to quantity, division and proportion, as is easily understood.” Bowers mentions this principle in passing but failed to follow up its implications.

Proportions are like the cog-wheels of a clock, regulated by the steady pendulum-like swing of Tactus. Once the Tactus is set (around minim = 1 second), there are only these three Proportions available: slow sesquialtera (3 semibreves in 2 tactus beats); medium-fast tripla (3 minims in 1 tactus beat); fast sestupla (6 semi-minims in 1 tactus beat). Any further multiples would be ridiculously slow or impossibly fast.

During the early seicento, composers increasingly used written instructions and/or such words as adagio, allegro, presto etc. to modify the basic information given by the note-values. Often, those modifiers exaggerate the contrast in activity already shown. Always, these modifiers indicate subtle gradations around a ‘ball-park’ tempo shown by the note-values.

Monteverdi’s notation

Triple Proportion uses mostly long note-values, which proceed proportionately faster than in duple time. So we recognise the final Moresca of Monteverdi’s Orfeo as Tripla Proportion (organised in units of three minims, structured as semibreve-minim), even though the ternary mensuration mark is missing. It would make no sense to play this in duple time at minim = 60.

The note-values of ternary proportions can be written in ‘white notation’ or ‘black’.

Under a ternary mensuration mark, a white semibreve might sometimes be ‘perfected’ to be worth three minims. A black semibreve – a black blob – is always worth only two minims.

In white notation, a semi-minim might look like a ‘white quaver’, but more often it looks like a regular crotchet. In black notation, a black minim looks like a regular crotchet, and a black semi-minim looks like a regular quaver.

Sometimes black notation is introduced in the middle of a section of white notation. This can produce ambiguities: is this thing that looks like a regular crotchet, i.e. a blob with a stick, a ‘black minim’ or a ‘white semi-minim’? But – once you get used to the two notations – this is less confusing that it might seem at first.

Badalla’s notation

Moving on from Monteverdi and Cima to Badalla’s Motetti, we again see three sets of note-values for the three ternerary Proportions. But there has been a change. For Badalla, the alternative notations of ‘white’ and ‘black’ note-values have simplified into something that looks more like modern usage, though we still need to be careful in understanding the significance.

We can see this change in progess within Leonarda’s oeuvre: three old-style ‘black minims’ under a mensuration mark of 3 or 3/2 are replaced with (identical-looking) crotchets and a time signature of 3/4: this is the new-style Tripla.

In Badalla’s 1684 publication, the slowest ternary metre is now shown with three white minims and 3 or 3/2. This is the new notation for slow Sesquialtera: the old notation with three semibreves has fallen out of use. A new fast notation appears: six quavers with a time signature of 6/8. This is the new Sestupla.

Both Leonarda and Badalla use the mensuration mark 3 to indicate ternary Proportion in general. Since the choice of proportion is governed by note-values, this mark is not ambiguous.

Leonarda’s publications vary between old and new styles of notation. I have only seen one example of both notations within the same collection, and the two styles are never used in a single piece. Movements in three semibreves identify the old style, time signatures of 6/8 etc identify the old style. We need to know which style is at work, in order to understand the meaning of three minims (old-style Tripla, new- style Sesquialtera).

Tempo-modifying words

Any of these strict Proportions can be subtly altered by modifying words: adagio, risoluto, allegro, presto [from slow to fast]. And in a section notated in duple time, C, the Tactus can also be modified by these words. The effect of Proportional changes between duple and triple is often exaggerated: e.g. from standard C [ordinario] to 6/8 presto. Sometimes the contrast is reduced: .e.g from C [ordinario] to 3/4 adagio.

There can also be subtle changes whilst keeping the same mensuration, e.g. in C from ordinario to adagio and then back to risoluto.

I have not seen the terms giusto or ordinario in the nun’s repertoire. This is unsurprising: if we see C (or any other marking of time) without any modifying word, then the tempo should be ordinario, giusto (correct).

Following some temporary modification, a return to tempo ordinario is shown by plain C (or a proportional mark). In Badalla’s Tacete o la, Tacete it is not clear whether risoluto signifies here an entirely new ‘resolute’ feeling, or a return to what we would nowadays call tempo primo. I would suggest that it hardly matters in this case, since a risoluto delivery of the opening phrase would be perfectly appropriate.

The words giusto and ordinario are also rare in Handel’s ouevre, though he sometimes writes them (as a warning against excess, or in order to emphasise a return to normality after some dramatic extreme).

20th-century Ur-text editors often supply [Allegro] where a first movement has no modifying word: we can now understand that this is incorrect. The proper editorial comment would be [Tempo Ordinario] or [Tempo Giusto]. Allegro is not the default choice for an opening movement, rather it is somewhat faster than the usual ordinario.

Handel’s notation

It’s generally agreed amongst specialist scholars investigating high baroque notation of tempo that 18th-century composers continued – even increased their ability – to indicate tempo as precisely as possible. See for example Julia Doktor’s Tempo & Tactus in the German Baroque here. Indeed, very fine details of subtle differences could be indicated, by combining three levels of gradation: coarse, medium and fine.

This fine-meshed array of possible tempi was calibrated to tempo ordinario (normal time). The alternative name of tempo giusto (correct time) reminds us that composers indicated the correct tempo, it is not the performer’s role to make arbitrary decisions. Nevertheless, tempo ordinario is not defined by any mechanical device, but by the subjective, human feeling for Time itself.

Handel’s Proportions

Proportions (3/2, 3/4, 6/8) define the broad parameters for relating one movement to another. A quaver in 6/8 is nominally twice as fast as a crotchet in 3/4, which in turn is twice as fast as a minim in 3/2. In practice however, those 6/8 quavers might be significantly faster than 3/4 crotchets, but not as much as twice the speed. Similarly 3/2 minims are significantly slower than 3/4 crotchets, but perhaps not as much as twice the duration.

C and C/ are similarly a 2:1 ratio in theory, but not so far apart in practice. If we consider the minim Tactus in C as the standard, then the semibreve Tactus in C/ can be somewhat slower.

Two opposing principles are at work. Smaller note-values are expected to have shorter duration, maintaining contrast. This principle tends to favour a slower beat if the Tactus is on a greater note-value.

Contrariwise, practical considerations discourage excessively slow tempi for long note-values, or exaggeratedly fast tempi for short note-values. So the Tactus beat might be slower, if there is a lot of surface activity in small note-values (reducing contrast).

These two opposing tendencies can be traced back to the early seicento. It seems the preference is to maintain or indeed exaggerate contrasts in surface activity at proportional changes, whilst taking a slower beat for a section with decorative passage-work, for practical convenience. Within each section, the Tactus is steady.

In theory, 18th-century Tripla Proportion still assumes constant Tactus, with C minim = 3/4 dotted minim. In practice, this sets up two alternative sets of Proportions, depending on whether the fundamental duple Tactus is based on C or C/.

In French-influenced music, a great variety of subtly different triple metre tempi are found, defined by dance-type. Each dance-type has its own mouvement, which specifies not only the speed of the Tactus beat, but also the rhythmic structure within that beat, and the emotional feeling associated with music and dance-steps.

Thus Tempo di Minuetto is poorly translated as ‘Minuet-speed’. Rather, the music should ‘move’ like a minuet, ‘swing’ like a minuet, ‘feel’ like a minuet. Carissimi’s declaration that tempo and mouvement convey the Quality of music must be linked to Muffat’s explanation, in Florilegium (1698) here, of vrai mouvement in Lully’s dance-music.

Handel’s Time Signatures

In the first half of the 18th century, variant time signatures within each Proportion give medium-level information. 3/8 goes faster than 6/8, which goes faster than 12/8.

Modifying words

The information given by time-signatures is thus already quite precise. And tempo-words give the last fine adjustment. Composers are able to show both clarity and subtlety in their markings.

Tempi in Handel’s Messiah, here.

Tempi in Handel’s Orlando, here.

International online seminar about about tempo, featuring Domen Marincic & Julia Doktor, here.

FOR MODERN PERFORMERS

There are two essential principles to guide modern performers towards late-17th- and 18th-century composers’ intended tempi.

1. The same notation [time signature and tempo word] implies the same tempo.

So we can compare similarly-notated movements, to find the speed that “works” for all of them

2. There is general agreement about the ORDER (slow to fast) of the various notations.

So we can rank the various movements in order, and compare near-neighbours to establish subtle differences.

The entire spectrum might be moved one way or another, according to the size of the ensemble, venue acoustic etc. But these two principles still hold. And, combined, they leave very little ‘wiggle room’, (especially in the 18th-century).

We can have a very good idea of composer’s wishes. We do NOT need to invent our own tempi.

WARNING!

Modern performers need to be aware of a crucial difference between our own ‘instinctive’ assumptions and baroque practice. We tend to look first at the tempo word, and take little notice of the time-signature as a source of tempo-information.

Baroque practice was the opposite: the time-signature gives the basic information, which is modified only in a subtle way by any tempo word. And that tempo word influences the character of the movement, more than the raw speed.

Badalla’s Time Signatures

Badalla’s use of proportions (the “denominator” of each time signature) and tempo-modifying words is clear. Her practice lies on the pathway from Monteverdi and Cima via Leonarda towards Handel.

But it is less certain how we should understand her use of variants (the ‘numerator’ of each time signature). These time signatures were not part of earlier practice, but we have a good understanding of how they are used by generations of composers following Leonarda and Badalla (see Handel’s Time Signatures above).

My suggestion for Badalla’s generation is based on the experience of studying this repertoire with actual, physical Tactus-beating. And I assume that late 17th-century practices are likely to represent a transition between early seicento and early 18th-century practices (each of which is better understood in current scholarship than the transition in-between them).

I suggest that Badalla’s 6/8 (standard Sestupla) could be beaten with a down-stroke on the down-beat of each 6/8 bar. This is approximately 1 down-beat per second at tempo ordinario.

In 3/8, the note-values have the same duration, but the beat is now a down-stroke on the down-beat of each 3/8 bar. This is a very fast (about 2 down-beats per second), vigorous beat, creating a very different feeling.

In 12/8, the note-values again have the same duration, but with a down-stroke on the down-beat of each 12/8 bar. This is a slow, steady beat (down for one second, up for one second).

Try beating each of these in turn – 6/8, 3/8, 12/8 – to appreciate the physicality of Tactus. Physical Tactus-beating produces strong contrasts in emotional Quality, even though a quaver has the same Quantitative duration in each case (as Carissimi tells us).

In theory, the note-values have exactly the same Quantity, only the Tactus beat and the subjective Quality changes. In practice, a very energetic 3/8 beat might produce a faster speed than the calm 12/8 beat. And over the years, this tendency would lead towards to the conventions that we observe in early-18th-century usage.

RHETORIC

This article has been concerned with rhythmic notation. But we should always keep in mind the other top priority of baroque music: Rhetoric, which in vocal music can be studied directly via the sung text. Even in instrumental music, the concept of music as a Rhetorical Art implies that we play as if there is a text being sung. .

Text defines articulations from syllable to syllable; and also affetti, emotions, from word to word; and the general mood from movement to movement. Thus Frescobaldi characterised his harpsichord Toccatas as having vocal affetti and a variety of movements, passi.

To find the affetto of an instrumental movement, Frescobaldi recommends that you play it through (at standard tempo), which will reveal the emotional character. This emotional character will then subtly adjust the standard speed in the appropriate direction. Tempo-modifying words work similarly, to adjust the basic significance of mensural notation. More on Frescobaldi here.

As we have seen, Badalla has at her command a sophisticated system of proportions, time-signatures and modifying words to indicate her intentions for tempo. As modern performers, we need to reconcile our understanding of the sung text with these details of musical notation.

We can assume that the composer has already responded to the affetto of the text, so that her tempo-indications can help us appreciate how she is responding to that text. Notations of tempo help us understand the emotional content.

We can also examine the affetto directly from the text in order to understand how the music, and our performance of it, might respond. This can guide us to changes of tone-colour, intensity etc, within the steady Tactus of each movement. It might even suggest moments where the singer is early or late on the beat, whilst the Tactus continues steadily. Read more about the baroque ‘Ella Fitzgerald rule’, here.

The text can also help us understand the tempo required for an entire movement, though we should not lightly abandon the composer’s own tempo-indications. If we think that the text requires a different tempo from that indicated by the musical notation, it is probably we who are wrong, rather than Badalla!

Word by word, movement by movement

Two techniques can help us avoid imposing our own preconceptions, in order to approach the text from a period perspective.

Word by word, the appropriate manner of performance is defined by the word itself. Amore does not imply singing piano, or slow, or legato: we should sing the word lovingly. Fuoco does not necessarily imply singing forte, or fast, or staccato: we should sing the word in a fiery manner.

We should avoid blurring meanings by substuting generalised musical instructions, rather we can take the word itself and turn it into a specific adverb, the precise way to sing this particular word.

Movement by movement, we can study frequently repeated and emotionally significant words, in order to determine which of the Four Humours is in play. This reveals subtle distinctions (love is Sanguine, desire is Choleric, unrequited love is Melancholy), and also gives general guidance to prevent us being misled by modern-day assumptions.

Leonarda’s dulcis flamma et ignis es (you [Jesus] are sweet flame and fire) might lull us into the expectation of a sweet, gentle mood, if we focus exclusively on the word dulcis, ‘sweet’. And certainly that individual word should be sung sweetly. But flamma and ignis clearly define the Choleric Humour, as the mood for this phrase and its repetitions as a whole.

17th-century music thrives on such short-term emotional contrasts dulcis flamma, whilst it is structured on the longer-term mood contrasts. This phrase is Choleric, but the movement (and the entire motet) ends in Sanguine hope, spes.

Summary

The baroque priorities of Rhetoric (i.e. text) and Rhythm were carefully observed and precisely notated by Badalla, as well as by previous and later generations, albeit in slightly different ways.

As performers, we do not have to summon up our own emotional response to the words nor choose our own tempo for the music. The text itself defines the emotions on both short and long-term levels, and the music notates the appropriate tempo.

The challenge, in this and all HIP music-making, is to understand historical information, rather than inventing our own ‘truth’!

“18th-century practice was the opposite: the time-signature gives the basic information, which is modified only in a subtle way by any tempo word.”

I doubt about this. La Chapelle, who gives pendulum indications for dances (1737), writes sometimes “se notte aussi par …” and gives then an alternative measure, e.g. 6/8 for 6/4 or 2/4 for 2/2. The tempo would be obviously the same. There is no tempo word, but the character of the dance may be taken as such.

For Quantz (1752) the notes per bar in combination with the tempo word are relevant, not the time signature. An Allabreve-Allegro with quavers has the same beat-tempo as a C-Allegro with semiquavers; the same holds true for 3/4 compared to 3/8.

Dear Klaus,

Thank you very much for your comment. I agree. And thank you especially for your citations.

My original remark was in the context of Italian music and movements that are not dances. I have now re-written the whole section, to differentiate between dance and non-dance contexts, and to include the question of surface activity.

I stand by my remark in its original context, and I hope my re-write has now clarified my meaning. Of course, I’m only touching lightly on both Monteverdian and Handelian notations, in order to set the context for considering Badalla’s intentions.

I would suggest that there are two parallel processes at work in the late 17th-century: Italian music is introducing new time-signatures and increased use of tempo-modifying words to provide both greater choice and improved precision in notating ‘tempo’. ‘Tempo’ means not only speed, but also the emotional Quality.

Meanwhile French music is creating dance-types with subtly different characters, and different rhythmic organisations within the bar, even though the basic metre (binary or ternary) and raw speed might not vary much between one dance and another. Meanwhile, those dances can be physically performed at various speeds, depending on the skill of the performer, the amount of choreographic complexity, the social situation, etc, etc. Plus all the usual musical variables of venue, acoustic, size of ensemble etc etc.

So whilst the ‘mouvement’ of each dance-type (meaning its characteristic steps and emotional quality) was well-defined for period musicians and dancers (even if tantalisingly difficult for us to rediscover nowadays), the raw speed might vary over a wide spectrum. Also, a ‘typical’ speed for a certain dance-type might lie ‘in the gap’ between purely mensural understandings of 3/4 and 3/2, for example.

I would read La Chapelle’s remarks in this French, dance-music context. And in that context, I would agree that the mensural system is close to breaking point, and that the most vital information is given by the name of the dance-type, which indicates what Muffat calls ‘le vrai mouvement’, meaning both ‘speed’ and ‘character’, as well as the physical movement of the dance-steps.

And now I’m going to cop out by declaring Quantz “beyond the scope of this article”! In general, I read him in the context of the 18th-century ‘mixed taste’, and I would hesitate to try to apply his principles retrospectively. But there is a huge project awaiting, to re-read Quantz in the light of the latest scholarship in French, Italian and German music of the previous generation.