It’s one of the best-loved and most well-known pieces in the Early Music canon, but what would you focus on, if you were asked to direct it, with the first rehearsal starting in a few hours time?

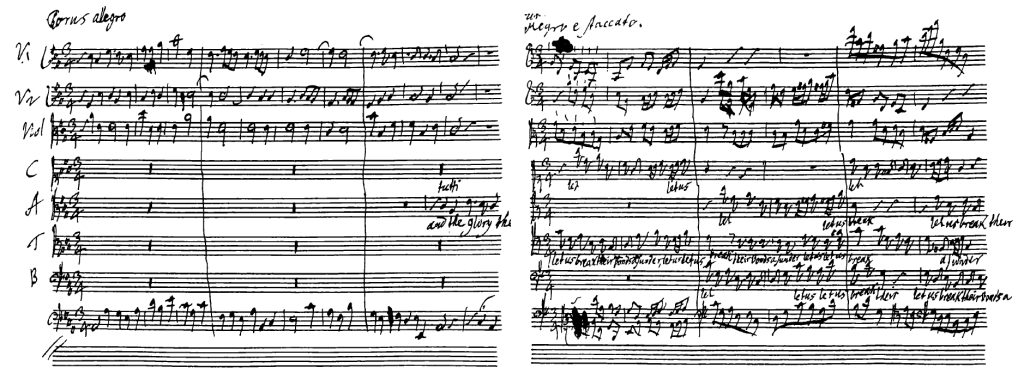

Finding myself in precisely this situation, I went to the autograph MS (here), in order to strip back all the accretions of generations of editors, and to check the original tempo markings: at the beginning of each movement, where there are any changes within a movement, and whether there is any fermata for a cadenza, or perhaps a final adagio [both these last surprisingly infrequent].

There are many movements of course, and Handel uses a large number of fine gradations of tempo-detail: andante larghetto, andante & andante allegro; allegro larghetto, allegro moderato, allegro.

This grand spectrum of tempo-marks is centred on tempo ordinario and time-signature C. There are cross-links to alla breve C/, and to triple 3/4, and 3/8, and to compound 6/8 and 12/8. In principle, we expect to find proportional relationships: smaller note-values indicate definitely faster tempi, so 3/8 is significantly faster than 3/4, perhaps twice as fast. Tempo-words might also produce a proportional change: in the Overture, allegro moderato might be twice as fast as the opening grave. But in practice more beats in the bar suggest a slightly slower tempo, so 12/8 is somewhat slower than 6/8. And subtle shifts in character or changes in articulation create small adjustments to mathematical proportions.

Given all this information, there is a simple, but surprisingly powerful performance-research technique: take all the markings, and assemble a list, in order from slowest to fastest. Handel uses so many different markings, that once you have them in order, there is not much ‘room for manouevre’ in deciding the actual tempo for each marking. Read more about Handel’s tempo-markings Of course, you may want to bias the whole spectrum to the slow end, or to the fast end, depending on performing forces and venue acoustics. See a recent international discussion about 18th-century tempi.

Most significant of all, and a good way to apply this research-technique in first rehearsal, are the groups of movements that have precisely the same combination of time-signature and tempo-word.

Simply trying each of these movements, and searching for the tempo that “works” for all of them, produces some surprising results, surprises which clearly reflect Handel’s wishes.

So last night I made the ordered list, and this afternoon I compared several groups of movements that share the same combination of tempo-information.

And now I’m off to first rehearsal. Where’s the dog?

Pingback: Measuring musical time in late-17th-century Italy | Andrew Lawrence-King