Following on from previous posts on Historical Action – Start Here, How to Act and Baroque Gesture – this article offers a new approach to period acting that is utterly historical, but significantly different from the coaching methods usually applied today.

The oft-repeated dictum ut pictura musica (music is like a painting) is often recognised in the 16th- and 17th-century practice of madrigalism or ‘word-painting’, in which the composer carefully matches musical effects to elements of visual detail described in the text. But this is only one manifestation of the renaissance concept of Enargeia, the emotional power of detailed visual description. And in turn, this connects to the historical science of emotions, with the idea that imagined Visions in the mind send Energia,the Spirit of Passion down into the body, altering the balance of the Four Humours and producing the physiological changes of emotional response.

In vocal music, the emotional content of the text – affetto – is matched by an effective turn of phrase or an ornamental ‘special effect’ – effetto – which in turn can move the listeners’ emotions – muovere gli affetti. Similarly, visual detail in the text – enargeia – allows composer and performer to ‘paint the words’ in music. The audience receive this vision via many channels – the sung text, the composed music, vocal timbre, the performer’s gestures and Action, even by direct beams of energia flashing from the performer’s eyes – and the energia of their own minds converts the poet’s enargeia into a physically evident emotional response. The two pairs of words, affetto and effetto, enargeia and energia, are closely inter-related.

The listener’s visual perception is crucial to this period understanding of emotional communication. So poets call for attention with such words as “Behold!” or “See!”, and performers employ gestures to emphasise visual details in the text. Those gestures have intrinsic beauty, variety and drama of their own, with contrasts of height and direction, all carefully coordinated with facial expressions and the focus of the performer’s gaze.

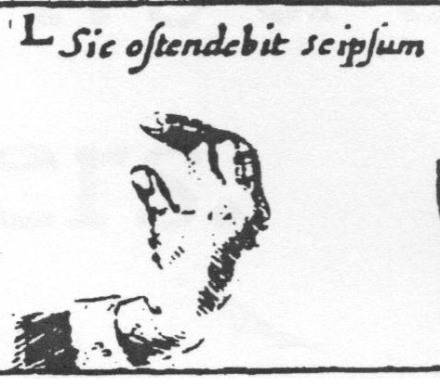

There is a historical notation for all this complexity of gesture, and a good way to study is to learn that notation in order to perform surviving examples of gestured texts. In The Art of Gesture, (1987), Dene Barnett explains the notation and reproduces some early 19th-century examples, recommending this course of study. A four-letter code specifies the action of the right hand: phfd indicates prone horizontal forward descending; seqn means supine elevated oblique noting. Two groups of three letters describe both hands: phq—pdb has the right hand prone horizontal oblique with the left hand prone downwards backwards. There are additional markings for the attitude of the head, the direction of the gaze, the position and movements of the feet.

Use of notation also allows modern-day performers and directors to fix a particular realisation of gesture. Following Barnett’s lead, many directors, especially those with a background in baroque dance, have taken the approach of fixing the gestures, and coaching performers to reproduce a carefully constructed realisation.

This approach has certain advantages. Gestures can be closely modelled on period sources and can be drilled repeatedly in rehearsal. Repetition and certainty help performers feel confident. Performers of lesser ability are given clear guidance to follow.

Fixing the gestures also has disadvantages. It can lead to a false concentration on the movement of the gesture itself, on the sign, rather than on the underlying meaning, what is being signified. It can disconnect gesture from text and meaning. Performers have less sense of ‘ownership’ of their gestures. The spontaneity that we prize in historically informed musical improvisation is entirely absent. Audience members intuit that such gestures are produced not by passion but by well-intended instruction. At worst, this becomes a ‘ballet of the hands’, beautiful to watch, historically accurate in superficial appearance but in a more profound sense, inauthentic and emotionally unconvincing.

These disadvantages have been observed and commented on, even in some of today’s finest productions ‘with baroque gesture’. They represent the most serious criticism of the entire practice of historical action, and the challenge to which Historically Informed Performers must now rise. This article offers an evidence-based solution: the ut pictura approach.

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,The lowing herd wind slowly o’er the lea,The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

To attempt to follow Austin’s annotated text is to become, inevitably, a clumsily articulated automaton, a mechanized monster of crippling self-consciousness.

Such an orator, like the hysteric, is the anxious object of an abstracting gaze, made to perform his every natural affect and impulse according to a predetermined plot.

Ut pictura: make a picture

and point out (to the audience)

what you see (in your mind’s eye).

The work of rehearsal is then changed. Rather than fixing each gesture, directors will lead a discussion with performers in order to fix the location/movement of each object in the imaginary picture. Of course, the picture needs to be consistent from one performer to another, and throughout the duration of the performance. It should also be consistent with baroque principles, e.g. Good Things are to the performer’s right, Bad Things are to the left. Period paintings can feed the imagination and inform the judgement.

The question I ask most frequently in gesture rehearsals is “Where?”

So in rehearsal with La Musica for the beginning of the Prologue to Monteverdi’s Orfeo: Del mio Permesso amato, a voi ne vengo [From my beloved Permesso, I come to you…], I would ask: “Where is Permesso?” (presumably behind the scene, as the performer walks forwards towards the audience, on the right since it is Good, and moving from high to low, since it is a river flowing from Mount Helicon into the Copaic lake). “Where are voi, the people the performer moves towards and addresses?” (presumably, the audience, directly in front, perhaps angled slightly to the right, to show respect for Good). Monteverdi sets mio as a long note, giving time for a gesture to oneself.

The more vivid your imagined picture is, the easier it is to point appropriately, and the more convincing your gestures will be. Once a detailed Vision is established in the performer’s imagination, coordination of gesture and eye movement/focus becomes automatic. You may find you need to take a half-step back, to take in a wider panorama, or half-step forwards to focus on some foreground detail: go ahead. But don’t shift your feet too much or too often – save it for key moments.

EXAMPLE:

BAROQUE GESTURE & UT PICTURA

Here is a worked example of the Ut Pictura method, applied to a well-known Elizabethan poem, a rhetorical discussion of poetry and music. In The Passionate Pilgrim (1840) the verses were attributed to Shakespeare, but are now known to be by his contemporary, Richard Barnfield. For teaching purposes, I have taken the liberty of substituting Shakespeare’s name for Spencer’s in line 7. Lutenist, singer and composer John Dowland is referred to in line 5.

If Music and sweet Poetry agree,

We can envisage Music as an English equivalent of Monteverdi’s La Musica, the personification of music. A beautiful women, holding a lyre, standing in classical pose. Similarly, Poetry is a personification, a handsome young man. Following the baroque convention of starting with the right hand, we might place our Music-woman to the right of our picture, and our Poetry-man to the left. As the opposing subjects of the rhetorical discussion to follow, these two should be placed opposite each other, separated, rather than together in the centre.

The imaginary picture-frame keeps our gesturing hands within natural and historical limits, more or less between waist and shoulders.

As they must needs, the Sister and the Brother,

Sister and Brother confirm the genders of the two personifications, and also their relative locations. Conventionally, the woman is accorded the respect of being placed to the right, as Good. These two gestures will (logically) repeat the precise direction and distance, since they refer to the same figures in the same positions as before.

Then must the love be great ’twixt thee and me,

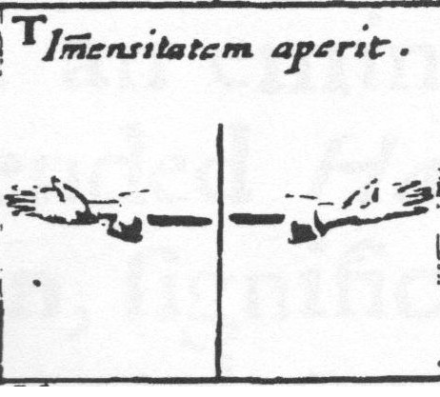

Great invites the conventional gesture to show immensity. To help performers remember this gesture, I often make the joke that it’s the gesture of a fisherman describing the one that got away: it was this big!

Thee, the person addressed, represents the audience, straight ahead, and further away than Ms Music and Mr Poetry. Me invites the usual gesture to self. The speaker and the person addressed are opposite one another, but on the forward/back axis, corresponding to Poetry and Music as opposites on the left/right axis.

Because thou lov’st the one and I the other.

Thou is the listener again, ahead and distant; the one is Music, right. I encourages the speaker to gesture to self; the other is Poetry, left.

The locations of the personages are obvious and fixed. But a performer can choose, spontaneously, how to deploy the hands to point them out. For example, Thou and Music with the right hand, I and Poetry with the left, makes elegant movements and leaves the hands attractively outspread. Leading the right hand is a good general rule.

Dowland to thee is dear,

Dowland appears here as the champion of Music, so on the right side, but not as far right as Music herself, in order to give the woman the honoured position to the right of the man. As a lute-player, he is seated, whereas Music and Poetry are standing. Thee is the addressee, in the audience, forward and further away.

whose heavenly touch

Upon the lute doth ravish human sense;

The touch is Dowland’s fingers on the Lute, which presumably is on his lap.

Shakespeare to me,

As the champion of poetry, Shakespeare should be placed to the left, in the corresponding position to Dowland’s on the right. I imagine him holding a manuscript script and a quill-pen. There might be sufficient time for a self-referring gesture for me, but the intention could also be clarified by a smaller movement of the hand, and/or a change of gaze.

It’s important to keep it clear for the audience that the following lines refer to Shakespeare and not to me, so if the point of the lines is to characterise Shakespeare, the pointing hand should be directed towards Shakespeare too. In both meanings of the word, directing the audience’s attention is the point of baroque gesture.

whose deep conceit is such,

As passing all conceit, needs no defence.

[The Elizabethan word conceit does not mean pride, but rather ‘artistic concept’.]

These lines at first appear very abstract, a rhetorical flourish that does not suggest any specific gesture. Certainly, one could employ the Default Gesture (see How to Act here), and allow one’s mindful concentration on the words being spoken shape that gesture appropriately. However, there are three metaphors here that contain visual description, elements that could be assembled in a temporary picture. Shakespeare’s ideas are deep, they go past all other ideas, and they do not need any defence. This suggests a temporary picture, an inset within the larger picture of the whole poem, in which something goes deep, moves to pass other similar things, followed by an mental image of defence. Hand-to-hand fighting, 17th-century rapier, or an Elizabethan castle perhaps. What is your historical image for the word defence?

It is the mind that creates a picture here. The hands might point to elements of the picture, to the deep place, or to whatever defending is going on. But the hands do not mimic those elements – this is a subtle but essential distinction that many historical sources emphasise. And we need not be daunted by the abstract nature of conceit (in its period sense of ‘idea’, ‘concept’). It is typical of the 17th-century mode of thought to characterise abstract qualities as personifications. Just as we have beautiful La Musica, so we can have clever Master Conceit.

Also, note that although the clause concerning defence is negative, the gesture nevertheless corresponds to defence rather than to the absence of it. Try for yourself what gesture you make when you say “I don’t have my phone“: do you make a sign for a phone, or for an empty space?

Thou lov’st to hear the sweet melodious sound

Thou is the addressee once again. Sweet melodious sound might seem difficult to imagine visually, until we remember that 17th-century science considered sound as travelling invisibly through that mysterious invisible substance, the Aether. So the eyes and pointing hand search for something that cannot be seen, but which travels towards the ear. If you sharpen your ears to listen for this invisible melody, you will find yourself tilting your head and turning one ear towards the origin of the sound. This is a gesture described in period sources, but (like the pointing gestures) it works better if you imagine the sound and listen for it intently, than if you focus on reproducing the mechanics of the gesture.

That Phoebus’ lute, the queen of music, makes;

Phoebus is Apollo, the god of music and of poetry. Stage conventions put the most important personage of a larger group front and centre, so this would be an appropriate placement for Phoebus. We envisage him seated – a symbol of kingly power – and holding his Lute, and perhaps turning towards Music. We might create a temporary ‘inset’ picture for the Queen – although this is just a metaphor, the poetic imagery calls forth a mental image.

And I in deep delight am chiefly drowned

I suggests another self-referring gesture. The poetic imagery here characterises delight as a something like a tidal-wave that sweeps over the speaker. Again, one should not mimic, but rather point to what is described. Eye-, head- and body-movement might be more effective than a hand-gesture, but in any case the speaker’s focus should not be on the execution of such movements, but rather on the imagery of the words being spoken.

Whenas himself to singing he betakes:

The key word here is Singing. Phoebus-Apollo is the god of music (represented by the lute) and of poetry (represented by singing). So we should now imagine Apollo as a singer, perhaps now turned towards the left, towards the personification of Poetry. One might even imagine Apollo putting down his lute, and standing up to sing- this would add movement to the picture and increase the power of the resulting gesture.

As often in a Sonnet, the final couplet reveals the underlying meaning, sums up the message, the conceit of the whole poem, and sends that message winging towards its recipient.

One god is god of both, as poets feign,

The number one can be shown with the vertically extended index finger (the same gesture also calls for Attention for these last two lines). Apollo is the god (front and centre) of both (simultaneously indicating Music far right and Poetry far left). As poets feign politely concedes lesser strength on the pro-poetry speaker’s own team, and disperses the attention to a wider audience (perhaps behind the addressee and to the left, as less important) of Poets.

One knight loves both, and both in thee remain.

The one knight is the speaker himself: there could be another counting gesture, or a referral to self. There is probably insufficient time to make both those gestures without unseemly haste, but the missing meaning can be conveyed by the eyes. Again, the performer’s focus should not be on “how do I show this meaning?” but on “what is the meaning I’m trying to show?”. So have some fun, imagine yourself as the one-and-only Elizabethan knight, complete with shining armour.

Both refers again to Music and Poetry simultaneously (right and left, respectively). Thee is the addressee, and this final clause underlines the point made earlier – ‘then must the love be great ‘twixt thee and me’. The one knight loves the music and poetry which are to be found within the soul of his beloved. This is consistent with the period philosophy of the Music of the Spheres, which sees heavenly music reflected in the microcosm of the harmony of human nature.

The final line invites the orator to conclude with eyes and hands directed towards the beloved addressee, and to remain there. Then as the vision dissolves and fades, leaving ‘not a rack behind’, the hands fall relaxed to the sides.

Conclusion

All this work of detailed positioning would be done by any competent director of baroque gesture, placing the hands at the appropriate angle and elevation to indicate each of the persons or objects referred to in the text. The crucial difference in my Ut Pictura approach is that the work is carried out not on the gestures, not on the hands themselves, but rather on the imagined picture of the scene. In period theory of emotions, it is the audience’s visions that produce an emotional response. Those visions are conjured up by the actor’s words and gestures: gestures create visions. The ‘reverse engineering’ of my title and method is to use the actor’s own visions to produce the gestures that will move the audience’s passions: visions create gesture.

I encourage actors to consider not “where do I put my hand?” but “where is Apollo?”. And this question is particularly effective as a rehearsal tool, because when as gesture coach I ask, “Where is Dowland?”, the actor will usually reply with a pointing gesture to accompany the word “There!”. That pointing gesture will be perfectly positioned, as long as Dowland is precisely located in the imagined picture.

Of course, the pointing has to be done with a well-shaped hand, the orator has to assume a historical posture. Plenty of rehearsal will be needed, to bring the imagined picture into sharp focus, and to time detailed envisioning to coincide with mindful attention on the word being spoken right now. Coaching must discreetly improve the historicity of the gestures, whilst ensuring that performers’ attention remain on the picture, not on their hands. But this method allows actors to ‘own’ their gestures, and to vary them spontaneously, or at the very least to choose spontaneously between several (well-rehearsed) options. And concentration on the picture will ensure that the gesture, be it thoroughly historical or work-in-progress, will strike the spectator as being honest and genuine – authentic.

Ideally, audience members will not even notice the gesture as such. Their attention too will be directed away from the hand itself, and towards wherever the hand is pointing. That‘s the point!

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our websites:

www.TheHarpConsort.com [the ensemble, early harps & Early Music]

http://www.IlCorago.com [the production company & Historical Action]

http://www.TheFlow.Zone [Flow for optimal creativity, The Zone for elite performance]

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago. From 2011 to 2015 he was Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions. He is now preparing a translation of Bonifacio’s (1616) Art of Gesture and a book on The Theatre of Dreams: The Science of Historical Action.

Pingback: Looking for a Good Time? | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: How to study Monteverdi’s operatic roles | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Baroque Gesture: what’s the Point? | Andrew Lawrence-King