How to ‘add beauty’

Around the year 1600, singers were expected to deliver more than just the bare notes written by the composer. There was a well-established practice of dividing up long notes into elaborate swirls of short and very short notes – passaggi. The new aesthetic of solo song accompanied by a plucked instrument favoured short-range vocal effects – effetti – the one-note trillo, the two-note trill and turn grupetto etc. These effetti were intended to convey emotions – affetti – and were used sparingly: period sources show less frequent application of effetti than we hear in most modern-day performances. The change from old-style polyphony and passaggi to seconda prattica monody and effetti was gradual, so that these four categories overlapped considerably during the early seicento.

But in his (1596) Prattica di Musica (Libro Primo, Chapter LXIII) here Ludovico Zacconi describes in detail a way to ‘sing gracefully’ that is not merely an ornament, but rather an essential characteristic of fine vocal delivery. First he emphasises the importance of pronouncing the words schiette, intelligibile & chiare (cleanly, intelligibly and clearly), and intoning the musical notes accurately (giuste – in tune) and briskly (allegre), not forced or slow. Loud high notes should not be shouted; it’s better to take a high piano notes in falsetto (fingerle – fake them) than to strain. All this takes about a quarter-page.

The remainder of the chapter (more than 2 pages) is introduced as a detailed analysis of how to carry the voice across intervals of a third or more, a particular skill in repertoires that generally favours movement by step. Zacconi’s goal is the ‘grace and poise … demonstrated by the ability to perform effortlessly, and with agility, adding beauty and decorum.’ (si ricerca gratia & attitudine…quando in fare un attione dimostrano di farla senza fatica & all’ agilita, aggiungano le vaghezze e’l garbo).

‘This can be recognised as akin to the difference between seeing on horseback a Cavalier, a Capitan, or a ditch-digger and a porter; and with what ease an expert and fine standard-bearer handles, displays and moves the flag, compared to a shoe-maker. (In questo si conosce quanta differenza sia nel vedder star a cavallo un Cavaliere, un Capitano o un Zappaterra & un Facchino: & con quanta leggiadria tenghi in mano, spieghi e mova lo stendardo perito & buono Alfiero: che vedendola in mano a un Calzolaio…)

Highlight by delaying & sustaining

Intervals of a third or more ‘are delivered with certain accenti caused by some delays and sustaining of the voice’.

(Le dette figure s’accompagnano con alcuni accenti causati d’alcune rittardanze & sustentamenti di voce) The term accento does not mean ‘accent’ in the usual modern sense of a sharp, hard intensification of the start of a note – Zacconi is looking for a ‘beautiful… sweet’ effect, and his accento is not applied to strong, powerful texts. Nor is it a particular way of pronouncing words, a ‘foreign accent’. Nor does it mean the accented syllable of the word – the period terminology for this crucial concept is the Good or Long syllable. Nevertheless, we would expect to find the accento on a Good syllable.

Rather, accento means a “turn of phrase” in poetry or music, a brush-stroke in fine art, or a “highlight”. We recognise this meaning in the lines ‘O let me hear Thee speaking / in accents clear and still’ from an 1869 hymn by John E Bode. And we hear it also in the Prologue to Monteverdi’s (1607) Orfeo: ‘I am Music, who with sweet accents can make tranquil every troubled heart’. Io la Musica son, ch’ai dolci accenti so far tranquillo ogni turbato core.

Zacconi’s characterisation of the accento as a fundamental element of vocal delivery explains why scholars have struggled to understand it fully in studies of treatises on ornamentation. Bruce Dickey’s excellent survey of Italian ornamentation in The Performer’s Guide to 17th-century Music (1997) here admits that ‘the actual form of the accento is somewhat elusive’ but continues to give several illuminating examples from Zacconi, emphasising that the period intention is ‘rhythmically vague and subjective’. Zacconi’s description of ‘delays’ and ‘sustaining’ defines the essential nature of this practice, giving a broad hint that we should include such rhythmic subtleties in our realisations of accenti from ornamentation treatises.

Zacconi states explicitly that this accento is an unwritten obligation: ‘the composer who writes the notes is only concerned with managing those notes according to what is convenient for harmonious progressions; but the singer who delivers them is obliged to perform them with the voice and make them resound according to Nature and the decorum of the words’. Il cantore nel sumministrarle e obligato d’accompagnarle con la voce, & farle rissonar secondo la natura & la proprieta delle parole. We should expect to hear these accenti frequently across intervals of a third or more, even though we do not see any indication in the written composition. Although Zacconi warns against excess, and mentions particular words that are unsuitable for accenti, it is clear that they were used more often than not.

Actually, there are some notations of accento-like delays in dramatic monody, in the published scores of the first ‘operas’. And this customary practice from the 1590s would have been part of the training and vocal habitus of the singers who performed in genere rappresentativo (in theatrical style) during the following decades. ’17th-century ornamentation practice is a blending of traditional of traditional practices bequeathed from the 16th century and innovative techniques developed in connection with the new monodic singing style fashionable after the turn of the century.’ [Dickey 1997]

Although we can certainly apply accenti to early-17th-century dramatic monody, the context in which Zacconi writes is prima prattica polyphony.

Nowadays, the best-known ensembles for renaissance a capella polyphony – many of them English and strongly influenced by their singers’ training in Oxford & Cambridge college choirs – maintain an aesthetic of “pure vocal lines”, homogeneity and legato that has its origins in the late 19th century. We rarely hear Palestrina, Lassus or Victoria with florid divisions, and the highlighted delays of Zacconi’s accento are unfamiliar even to historically informed performers.

Even though he warns against excessive sustain, the subtle delaying effect that Zacconi finds so beautiful must also strike modern ensemble-directors with alarm: how can the singers keep together, if one or another part frequently sustains the written note to arrive late on the next one, and even ‘highlights’ this effect? The insistence on vertical alignment that has been a central tenet of modern-day Early Music (particularly amongst CD-producers) seems to be contradicted by this unwritten, but fundamental and obligatory element of period practice.

How to carry the voice

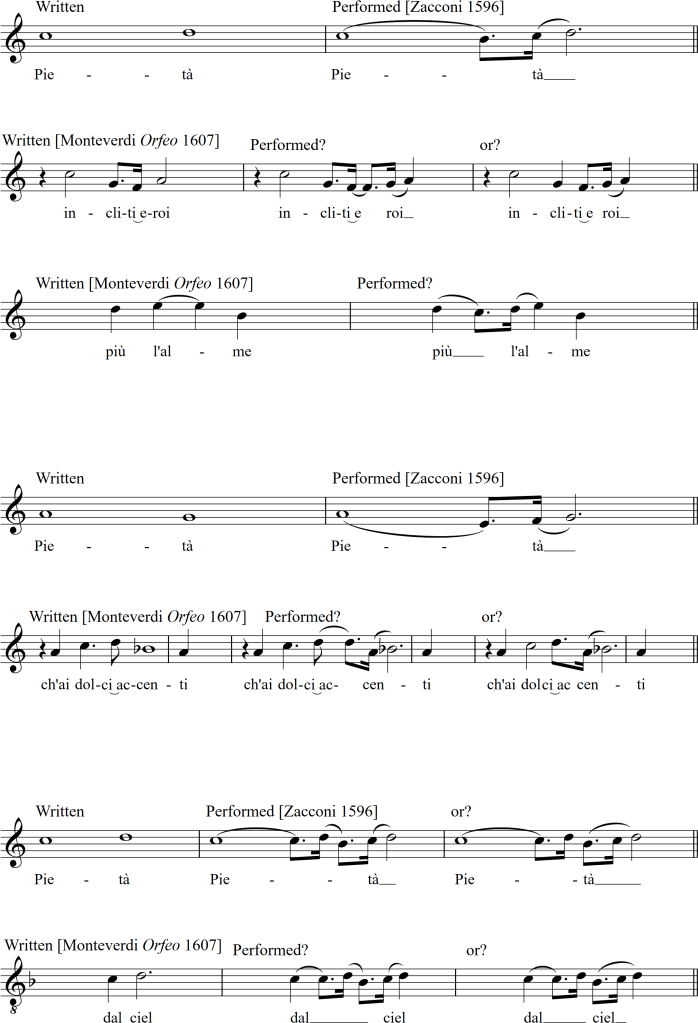

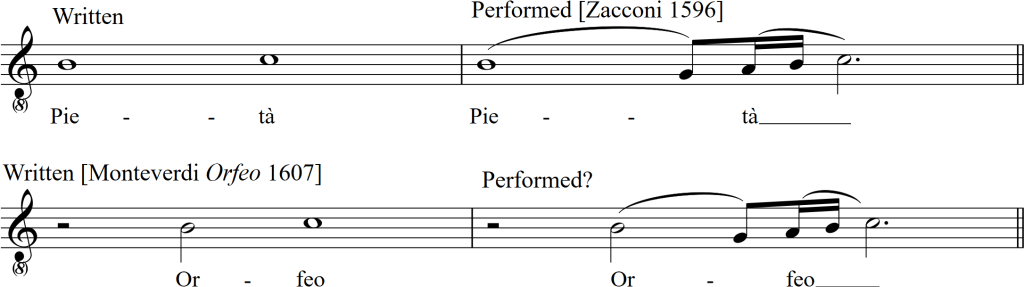

Since Zacconi’s context is vocal polyphony, it is well worth considering text (which he has emphasised in the previous paragraphs). In the transcriptions that follow, I have added a plausible text to Zacconi’s untexted examples. My assumption is that the note that takes the accento also carries a Good syllable. The shift in text-pronunciation produced by these accenti further highlights the effect of delaying.

We can expect that instrumentalists would have imitated singers in all these unwritten subtleties. ‘Singers… were the model for instrumentalists as well, who were to imitate the human voice as much as possible’. [Dickey 1997]

I have also added examples from Monteverdi’s (1607) Orfeo of written-out accento-like ornaments, and of situations when an accento might possibly be applied.

Subtleties

The accento is not applied to Ut-mi, nor between two hexachords sol-mi (e.g. G – B natural). But it can be applied to the major third fa-la (i.e. F-A, C-E, Bb-D, depending on which hexachords are available).

As Dickey (1997) remarks, the rising-third accento is similar to the intonazione on a good-syllable initial note, described by Caccini and notated by Cavalieri. In both practices, accento and intonazione, the central semiquaver is touched only very lightly.

Zacconi’s notated durations are approximate: the desired effect is ‘delightful and sweet’. The delay should not be excessive or heavy. The accento is subtle, beyond the limits of notation.

‘I’ve put a dotted quaver and semi-quaver so that singers see how to ascend; because there are some who – even though these beauties should seem natural – in pronouncing them, pronounce them so slow and late that by their languor they make a strange effect and do not give any good satisfaction to the ear. These are things that are difficult to demonstrate and make understood in writing. It’s necessary for the alert and diligent singer to adjust them according to what their own ears tell them is delivered well or badly.’

The accento should not be applied to every possible note.

‘This way of singing is a delightful and sweet way, and sweetness – although a friend to nature – is also cloying, and used too many times will produces disgust and boredom. Therefore it is not a good idea to use them always, in order to avoid giving listeners disgust and dissatisfaction.’

Accenti for seconds

Nevertheless, Zacconi moves on immediately to show how to apply accenti even to the the interval of a second, i.e. to notes that move by step! However, he rules out mi-fa and ut-re ascending, similarly avoiding fa-mi and re-ut descending.

My underlay is conjectural – other solutions are available! Where I have indicated alternative rhythms, the ideal may lie in subtlety of rhythm somewhere in-between the two notated versions.

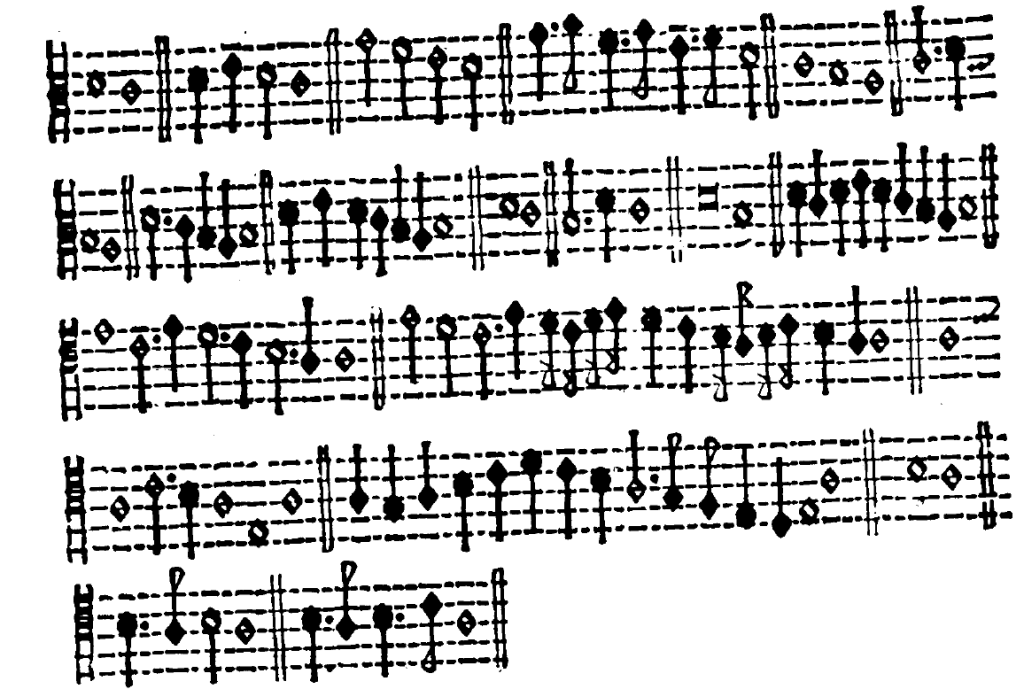

Accenti for fourths & fifths

For wider intervals, Zacconi requires a different style. The running semiquaver in the middle of the previous examples only works if it runs to an adjacent note, not across a leap. Again, Zacconi struggles to describe in words the subtle effect that he intends: ‘the little notes in the middle are pronounced beautifully without making them resound like a real note.’ Nel mezzo pronuntiarli con la voce quelle vaghezze senza farle rissonar per figure.

Whilst the accento delays the composer’s second note, the whole thing (i.e. both written notes) fits into the regular Tactus. ‘From beginning to end, the notes do not have more duration than they normally require’. Dal principio al fine non habbiano piu valore di quello che per natura ricercano.

Zacconi adapts his running formula for a rising fourth to give an alternative for a rising second mi-fa.

Zacconi concludes: ‘All these examples can be adapted and used as models for further possibilites. But as I have said, it is difficult to make these things understood without a sung example. For this reason, I will skip many vague things that might be said around this subject to say only this: when the Singer hears the beauties of a performer (I’m not talking about gorgie and passaggi…) he should try to imitate them as far as possible.

‘Singers should be warned that in imitative polyphony- fughe or fantasie – one should not delay any note, so as not to break and spoil the well-ordered imitation. Rather one should sing on the beat – equale – without any ornamentation.

‘There are also some notes that for the sake of the words do not need any accento, but only their natural and lively force, as when one has to sing Intonuit de Celo Dominus; Clamavit; Fuor fuori Cavalieri uscite; Al arme al arme [God thundered from heaven; he cried out; Go out, go out Cavaliers; To arms, to arms] and many other things.The discreet and judicious singer must decide’

This should remind modern readers that the accento is not a sharp accent, nor bravura display, but a sweet and subtle beauty.

‘On the contrary, there are other words that from their own nature demand these beauties and these lovely accenti, as when one is to say Dolorem meum; misericordia mea; affanni e morte [my sadness, have mercy on me, sorrow and death]. Without any further sign to the singer, these indicate how they must be sung.’

This instruction reinforces the impression that accenti are used very frequently, even if not always.

Other ways to beautify

The accento gives a subtle, soft highlight by delaying the main note. Zacconi now considers how to enliven the written notes, with simple divisions, which do not require the full inventiveness and technical proficiency of more extended passaggi.

‘We can also break up the notes with vivacity and force, which makes a very grand good effect on the Music’.

My assumption would be that these divisions would usually produce no shift of word-underlay, and certainly not the delaying effect of the accento. But in Zacconi’s second example (four notes descending by step), a lively effect might be created by anticipating the new syllable, placing it on the previous short-note.

Zacconi comments that these are just a few examples, many others could be given. Nature itself is the best teacher, and this is just an ABC for beginners. But since some students leave school not knowing these beauties and these accenti, Zacconi wants to get a few things down on paper for those who don’t have any decorum, or any good way of singing. He writes them down, not because they should be notated, but so that they can be added with the voice.

‘Finally, I must say that masters who teach these accenti and beauties should be warned to control the scholar so that they do not apply them too often, as if they would be done always. Because just as too much sugar spoils a fine, delicate meal, similarly so much sweetness and beauty placed together produces boredom and disgust. And for this reason we add so many dissonances to the Music, just because they redouble the sweetness of the consonances.’

Significance

Published at the very moment that the Baroque aesthetic of dramatic monody and continuo emerges from renaissance polyphony, and positioned in this crucial treatise as the first step towards beautiful singing (with a quick reminder to take care of the text, not to shout, not to strain) this chapter has enormous significance for today’s Historically Informed Performance. But it has been almost totally forgotten.

Although Zacconi warns us not to use the accento on every possible occasion, and limits it to words that do not contradict its natural property of sweetness. it is clear that around the year 1600 it was used very frequently indeed. In training and in performance, our modern-day Early Music seems to have lost sight of this fundamental element of beautiful singing – and playing.

It is also clear that the essential features of the accento are sustain and delay, even in polyphonic music. So how is ensemble synchronicity to be managed, if any voice might introduce a delay on any note (even if not on every note)?

Zacconi’s answer to this practical question of timing calls for a revolution in our understanding of ensemble music-making in this period, and – at last! – an end to the early 21st-century struggle between proponents of rhythm and of rhetoric. See my next post.

After this article about a forgotten ornament, you might like to read about another ornament, that perhaps we wish we could forget. Yes, THAT ornament.

Of course, there are plenty of alternatives available from historical sources, but if we are looking for better cadential ornaments, might we be asking the wrong question? Read more about ornamenting Monteverdi here.

Pingback: The Wrong Trousers: can new training re-purpose Early Music skills for Historically Informed Performance? | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Altri canti senza battuta: Madrigals of Love, War & Tactus | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Passaggi: Della Casa & Bovicelli on the True Way to make Divisions | Andrew Lawrence-King

Pingback: Making Time for beautiful singing: a lost practice | Andrew Lawrence-King

Many thanks for a truly fascinating and thought-prokoving article, Andrew

Thank you, Brian. Look out for the post “Making Time for beautiful singing” which examines the rhythmic consequences of applying Zacconi’s advice for frequent ‘accenti’….