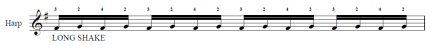

So I hope you’ve all been practising the Long Shake [see Irish Harp Ornament #1 here] and that it’s beginning to feel as if the fingers can do it ‘by themselves’, and starting to sound good. Don’t be discouraged if it takes quite a while to master these ornaments – they are not easy.

The late Mr Seybold, a celebrated performer on the Pedal Harp, being in a gentleman’s house in Belfast, in 1800, when Arthur O’Neill was present, declared his admiration of the old man’s shake on the Irish harp, which was performed apparently with the greatest ease and execution: admitting that he could not do it himself in the same manner on his own instrument, the shake being of the greatest difficulty on every species of harp.

Bunting 1840

Practise little and often. Practise slowly, getting everything absolutely right. And then take a risk, let loose a fast shake, and see if your fingers will fly. Then practise slowly again. Repeat ad shake-it-um.

So now your Shake is all ready to go, but how to use it?

Unfortunately, Bunting’s table of ornaments doesn’t tell us everything we need to know. It’s not complete (there are typical ornaments that he doesn’t list), it doesn’t necessarily cover every technical detail, and – most awkward of all – it doesn’t tell us how to apply the ornaments.

So we have to look at tunes, and see where each ornament might fit. We can look at Bunting’s published versions (to a greater or lesser degree arranged for pianoforte), and see where he writes each ornament. We can look at Bunting’s manuscript note-books for hints of what the old Irish harpers actually played to him, before he adapted their music for publication. We can make comparisons to European music of the same time. And we can make comparisons to traditional Irish playing, today.

When we look for opportunities to use our shiny new Long Shake in Irish music, there seem to be very few, especially in those tunes that have a real Gaelic (rather than European flavour). So although the Long Shake is a very useful exercise, and a typical feature of European 18th-century music, I don’t see many opportunities for it in Gaelic tunes of the period. Actually, I don’t see any opportunities for it in the tunes Bunting prints, following on from the ornament table in his 1840 book.

Challenge: can you find a Long Shake opportunity that I’ve missed? All three Bunting publications (1796, 1809 and 1840) are available free here, and Wikipedia provides a handy introduction to his work here.

Meanwhile, don’t panic, the last month of practice has not been wasted. Not at all! The Long Shake is the ideal starting point from which to study many ornaments, and here comes one of the most frequently encountered: the Cadential Shake.

A Cadence marks the end of a musical phrase, just as punctuation marks the end of a clause, or the end of a sentence. In period literature, we often see long sentences organised with light punctuation, continuing for many clauses, until terminated by a full stop. Similarly in music of this time: each short phrase will end with an intermediate Cadence, and a longer section, or the whole piece, will end with a Full Close.

Although European music has several melodic options for a Cadence, the most common Full Close in Gaelic tunes is the so-called Tenor Cadence. The melody descends to the final note, with a strong accent on the second degree of the scale just before end of the phrase. So in the Irish harpist’s favourite mode of G, many tunes end with a strong A before the final G.

EXAMPLE 1 Ta me mo chodlach I

(I am asleep and don’t waken me) after the William Forde MS (collected during the 1840s).

That strong A corresponds to the Principal Accent in poetry, typically on the penultimate syllable of a line of verse:

To be or not to be, that’s the QUEST-ion

For more on historical phrasing, see ‘The Good, The Bad and the Early Music Phrase’ here.

Often, this strong note will be longer than neighbouring notes – and when it is long enough, this is our opportunity for a Cadential Shake. Often, Bunting gives us the hint for a Cadential Shake with a Tr marking.

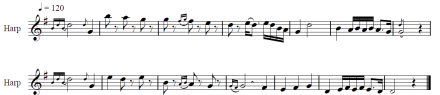

The first example of a Shake in the music of the 1840 collection comes on Page 2: Irish Cry. Bunting publishes this in Eb, so the Cadential Shake is on the strong F just before the end of each of the first three phrases, marked Tr by Bunting.

EXAMPLE 2 Irish Cry

Bunting 1840

In the usual G-tuning for Irish harp, we would play this piece a third higher, of course, and the Cadential Shake would be on A.

EXAMPLE 2A Irish Cry in G

The next example is on Page 4: Scott’s Lamentation. Bunting notates this in F, with a Cadential Shake marked Tr on the strong G just before the end of the first line. And another Cadential Shake Tr, on the strong D of the phrase ending on C in the next line.

EXAMPLE 3 Scott’s Lamentation

Bunting 1840

In the usual G-tuning for Irish harp, we would play this piece a tone higher, with Cadential Shakes on A and later on E.

EXAMPLE 3A Scott’s Lamentation in G

These first few pieces are those that Bunting regards as especially typical of the ancient Gaelic style. Not all of them have suitable cadences for a Cadential Shake (notice there was nothing on pages 1 and 3). But many of them do.

So, since this Cadential Shake is going to be useful, let’s see how to modify Bunting’s Long Shake, to work in the Cadential context.

As could be expected, the first modification is to shorten the Long Shake. Don’t try to make too many iterations of the Shake. Rather, shorten it to the available length of the Cadential note. [See how to shorten the Long Shake, here.]

Bunting gives another ornament, the half-Shake, which is very short, and we’ll examine that another time. For our Cadential Shake, we need bit more than this, but not very much more. Very often, the following (minimal) Shake is sufficient (and anything more would be too difficult).

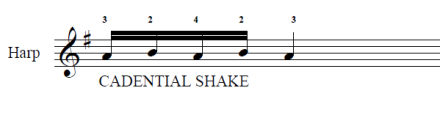

EXAMPLE 4 Cadential Shake

Notice that the Cadential Shake starts on the main note (the Gaelic way, Bunting tells us) and not on the upper auxiliary (the European way, according to many period sources, for example C.P.E. Bach).

Bunting doesn’t tell us any more, but I recommend that after reaching the last note of the Shake (the main note), you should damp the upper auxiliary note. This cleans up the sound, and steadies your hand ready to continue into the last note of the phrase.

So here is the Cadential Shake to practise:

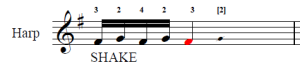

EXAMPLE 4A Cadential Shake with damping

Damp the crossed-out note, with the finger [2], let the red note ring on.

And here are the first Tr markings in Bunting’s 1840 collection, as above, but now realised with this Cadential Shake:

EXAMPLE 5 Irish Cry with Cadential Shake realised

EXAMPLE 6 Scott’s Lamentation with Cadential Shakes realised

Bunting’s metronome marks support his statement that the character of the Irish harpers’ playing was

spirited, lively and energetic

in contrast to the

languid and tedious manner in which they were, and too often still are, played among fashionable public performers, in whose efforts at realizing a false conception of sentiment, the melody is …. lost.

One last, but very important point. 18th-century sources emphasise that the Shake should begin louder and end softer. We can be sure that Seybold would not have admired O’Neill’s Shake, if this essential ‘dying fall’ was absent. So practise your Cadential Shake from loud to soft.

And that concludes this month’s posting. Have fun finding Full Closes in your Gaelic melodies, and adding Cadential Shakes to them. Compare the places you want to add a Cadential Shake to Bunting’s Tr markings. Do they mostly correspond?

As you will discover, not all of Bunting’s Tr markings are Cadential. There are some other opportunities for Shakes, and we’ll come to those in a later post.

Good luck, and Good Shaking!

Please join me on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/andrew.lawrenceking.9 and visit our website www.TheHarpConsort.com .

Opera, orchestra, vocal & ensemble director and early harpist, Andrew Lawrence-King is director of The Harp Consort and of Il Corago, and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre for the History of Emotions.